Le Petit Vampire fait du Kung Fu!, Joann Sfar, 2000, Guy Delcort Productions

or, if you prefer,

The Little Vampire Does Kung Fu!, Joann Sfar, 2003, Simon & Schuster

(because, despite the offensive roundtable title, we at the Hooded Utilitarian are all about ensuring your happiness and comfort)

I started reading French comics in high school (which was eons and ages ago, I will freely admit), at the suggestion of my French teacher. Magazines, too. Asterix and Paris Match. I haven’t picked up the latter in a while (although as a sheltered Midwestern teen in the Age Before Internet, damn, it did help to open my eyes to a few things), but Asterix, written by René Goscinny and illustrated by Albert Uderzo, certainly holds up. I have a small stack of French comics that I love, but I no longer read French very often, or very well. I do love me some Paris Vogue, but the secret to fashion magazines is to do the opposite of what you do with Playboy and never, ever read the articles, because that will make you want to kill yourself and take everyone you can reach with you.

So, approaching this roundtable, I had to do some thinking. I hate that. There are a couple of Little Vampire books I prefer to this one (although it does feature nunchucks, the eating and subsequent disgorgement of a small child by monsters, and a bizarre Jewish Zen parable, so I obviously do like it quite a bit), and there is a less amusing but still palatable Le Grand Vampire series, and there’s Donjon, an awesome series by Sfar and Lewis Trondheim. (You are, perhaps, noticing a theme in my post-high school French comics reading. Vampires and dungeons. I will also admit to suffering a certain amount of Goth-damage.) I am writing about the kung fu book, though, rather than any of these other books, because I had an auxiliary English copy of it that I could actually find. I have auxiliary English copies of a number of the vampire books (vampires both big and small), but they have vanished. Poof. Perhaps they flew out the window one windy evening to fly into the dark night sky and skulk around the dense and forbidding Carpathian forest with the wolves, remarking about the children of the night and the beautiful music they make. I wish them well. Fly and be free, big and little vampires!

It is only a minor setback, really; the sort of small frustration we all deal with every day. We do have the kung fu book in English, which means I can figure out what’s going on without getting out my dictionary, and it is in fact a pretty neat book, so off we go.

The plot is bland and soothing, like blancmange. A little boy, Michael, is visited late at night by his friend, the Little Vampire, and the Little Vampire’s posse, three monsters (my favorite is the Frankenstein-ish Marguerite, who loves poop). Michael explains that he’s being bullied at school by a loutish brat named Jeffrey and says he wishes the kid would die. Then the Little Vampire whisks Jeffrey away to his haunted castle so they can visit Rabbi Soloman, the kung fu master. Rabbi Soloman tells Jeffrey he’s left his kung fu book tied to the back of a dragon on top of an Angkor Wat-like temple, just through that door at the end of the hall, and that if Michael will bring him the book they’ll be set. Off Michael goes, getting his butt kicked repeatedly by monkeys, the temple itself (it is hard to climb and he keeps falling off), and by the dragon itself. Eventually, Michael gets smarter and better and he gets the book. Which of course says, “If you have managed to steal this book from the dragon, you are very skilled at kung fu. This book will teach you nothing more.” Because, you know, the only Zen on the mountain is the Zen you bring there. Anyway, now that Michael is all confident and proud and ready to take on the world and shit, he and the Little Vampire find out that the monsters went off and ate Jeffrey.

Zut alors!

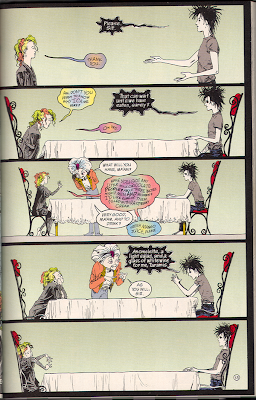

The Little Vampire does what anyone would do when faced with this situation – he makes the monsters cough up all the Jeffrey bits, and then they sew him back together. Then they go off looking for a magician to reanimate him. That doesn’t go entirely smoothly, as anyone who’s ever read any cautionary tale about magic would predict. But the ghostly pirate dude who’s kind of in charge takes pity on the boys and lets them off with time served. He gives the little boy, little vampire, and variously sized monsters the means for fixing Jeffrey. This involves what is without doubt my favorite panels of the book:

Moo!

The next day at school, Michael, now a kung fu master, picks a fight with Jeffrey, who remembers nothing of the previous night’s romp. And Jeffrey kicks his ass. It all works out, though, because the girl Jeffrey has a crush on beats Jeffrey up and nurses Michael’s wounds. So, the moral of the story is that it’s better to be an overconfident idiot than an actual martial arts expert. A lesson for all times, really.

Now, I know what you’re saying. “That’s a bit gluey, isn’t it? I can’t read that much treacle; I have blood sugar issues.” Fair enough. The bit at the end makes me gag, and not in a good way. I think the parts are better than the sum thereof, though, and some of the gags are worth the cutesy ending. The monsters coughing up the little boy they ate, for instance – that’s the kind of priceless I’m after. And the cow. God, I love the cow. So, there you go – the other side of Joann Sfar. (Assuming you read Vom Marlowe’s post Monday on The Rabbi’s Cat.)I hope you are moved to go forth and consume French vampire comics, in the language of your choosing.