I’ve avoided reading We3 for years, in part because I find depictions of violence against animals upsetting, and I was afraid I’d find it painful to read.

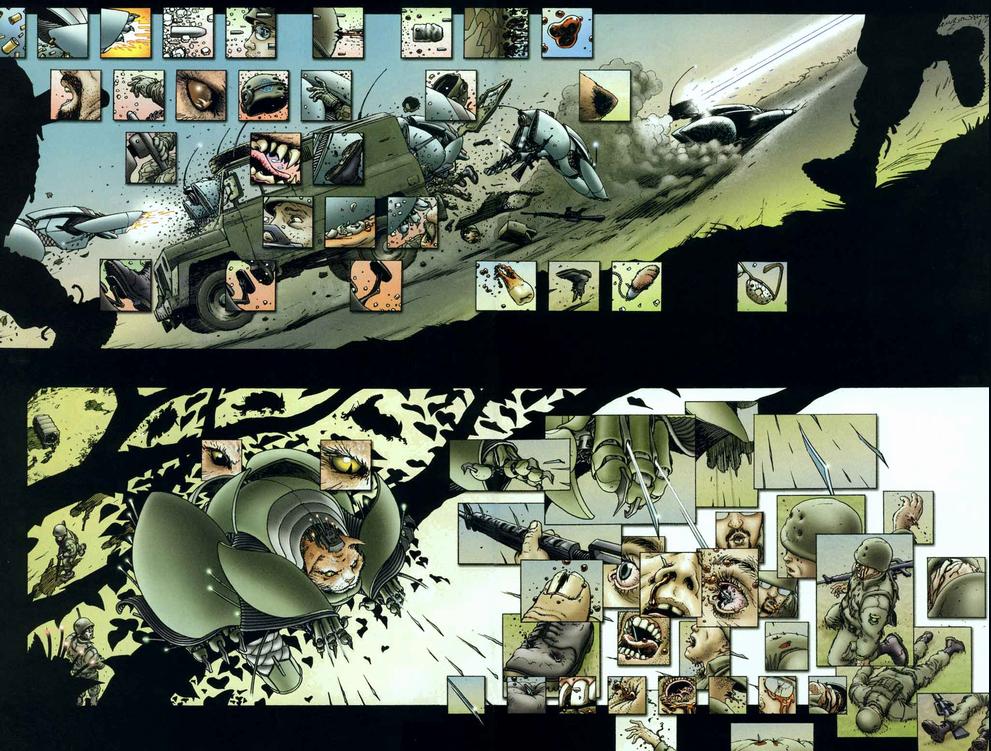

As it turns out, though, I needn’t have worried. We3 does have some heart-tugging moments for animal-lovers — but they’re safely buried and distanced by the towering pile of bone-headed standard-issue action movie tropes. There’s the hard-assed military assholes, the scientist-with-a-conscience, the bum with a heart of gold and an anti-fascist streak…and of course the cannon-fodder. Lots and lots of cannon fodder. We3 clearly wants to be about the cruelty of animal testing and, relatedly, about the evils of violence — themes which Morrison covered, with some subtlety and grace, back in his classic run on Animal Man. In We3, though, he and Frank Quitely gets distracted by the pro-forma need to check the body-count boxes.

The plot is just the standard rogue supersoldiers fight their evil handlers. The only innovation is that the supersoldiers are dogs and cats and bunnies. That does change the dynamic marginally; you get more sentiment and less testosterone. But the basic conventions are still in place, which means that the comic is still mostly about an escalating series of violent confrontations more or less for their own sake. It’s hard to really take much of a coherent stand against violence and cruelty when so much of your genre commitments and emotional energy are going into showing how cool your deadly bio-engineered cyborg killer cat is. To underline the idiocy of the whole thing, Morrison has us walked through the entire comic by various military observers acting as a greek chorus/audience stand-in to tell us how horrifying/awesome it is to be watching all of this violence/pathos. You can see him and Frank Quitely sitting down together and saying, “Wait! what if the plot isn’t quite thoroughly predictable enough?! What if the Superguy fans experience a seizure when they can’t hear the grinding of the narrative gears?! Better through in some boring dudes explicating; that always works.”

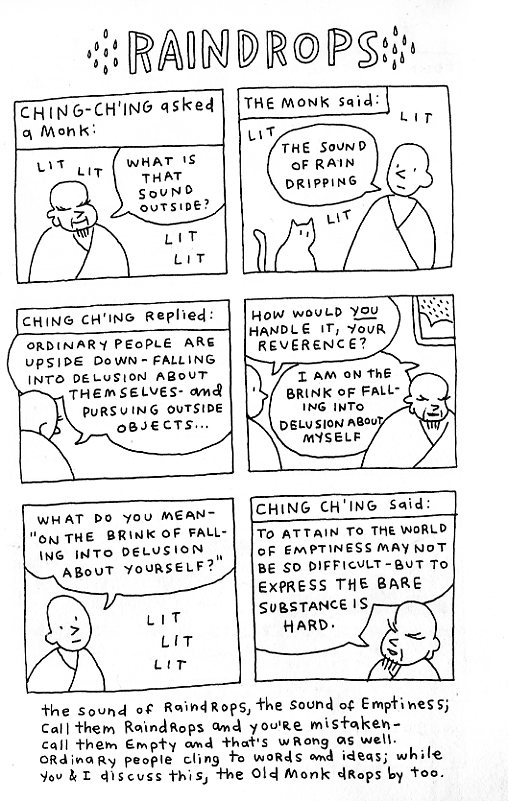

The point here isn’t that convention is always and everywhere bad. Rather, the point is that conventions have their own logic and inertia, and if you want to say something different with them, you need to think about it fairly carefully.

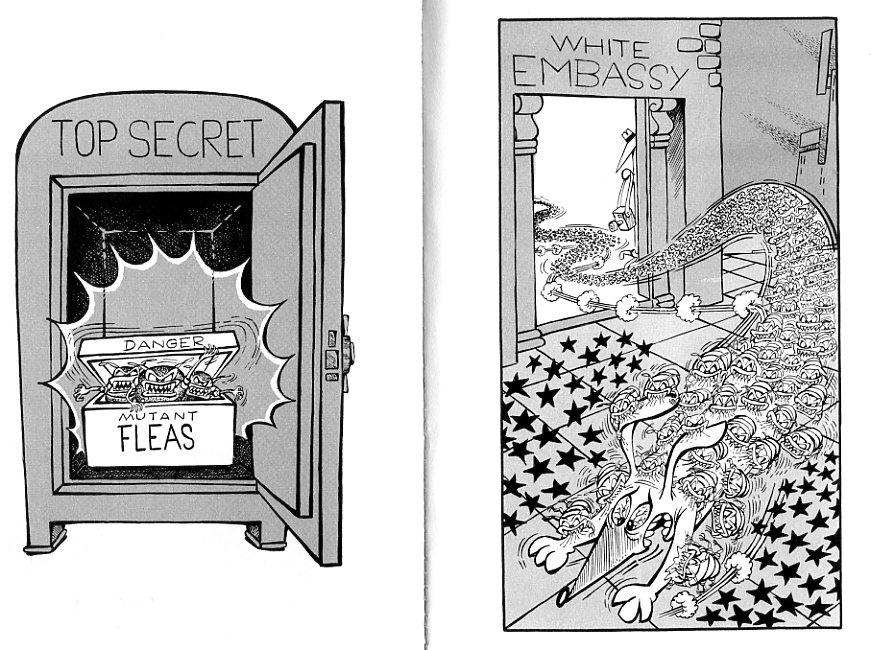

Antonio Prohias’ Spy vs. Spy comics, for example, are every bit as conventional as We3, both in the sense that they use established tropes (the zany animated slapstick violence of Warner Bros. and Tom and Jerry), and in the sense that they’re almost ritualized — to the point where in the collection Missions of Madness, Prohias is careful to alternate between black spy victory and white spy victory in an iron and ludicrous display of even-handedness. Moreover, Spy vs. Spy, like We3, is, at least to some extent, trying to say something about violence with these tropes — in this case, specifically about the Cold War.

Obviously, a lot of the fun of Spy vs. Spy is watching the hyperbolic and inventive methods of sneakiness and destruction…the black spy’s extended (and ultimately tragic) training as a dog to infiltrate white headquarters, or the white spy’s extended efforts to dig into black HQ…only to end up (through improbable mechanisms of earth removal) back in his own vault. But the very elaborateness and silliness of the conventions, and their predictable repetition, functions as a (light-hearted) parody. Prohias’ spies are not cool and sexy and competent and victorious, like James Bond. Rather, they’re ludicrous, each committing huge amounts of ingenuity, cleverness, malice, and resources to a never-ending orgy of spite. Spy vs. Spy is certainly committed to its genre pleasures and slapstick, but those genre pleasures don’t contradict its (lightly held, but visible) thematic content. Reading We3, you feel like someone tried to stuff a nature documentary into Robocop and didn’t bother to work out how to make the joints fit. Spy vs. Spy, on the other hand, is never anything less than immaculately constructed.

We3 doesn’t seem to realize its themes and conventions don’t fit; Spy vs. Spy gets the two to sync. That leaves one other option when dealing with genre and violence, which is to try to deliberately push against your tropes. Which is, I think, what happens in Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs.

Martyr’s is an extremely controversial film. Charles Reece expresses something of a critical consensus when he refers to it as “really depressing shit.”

And yet, why is Martyr’s so depressing…or, for that matter, why is it shit? Many fewer people die in Martyr’s than in We3; there are fewer acts of violence than in Spy vs. Spy. Even the film’s horrific finale — in which the main character is flayed alive — is hardly new (I first saw it in an Alan Moore Swamp Thing comic, myself.) So why have so many reviewers reacted as if this is something especially shocking or especially depressing?

I think the reason is that Laugier is very smart about how he deploys violence, and about how he deploys genre tropes. Violence, even in horror, generally functions in very specific ways. Often, for example, violence in horror exists in the context of revenge; it builds and builds and then there is a cathartic reversal by the hero or final girl.

Laugier goes out of his way to frustrate those expectations. The film is in some sense a rape/revenge; it starts with a young girl, Lucie, who is tortured; she escapes and some years later seeks vengeance on her abusers.

But Laughier does not allow us to feel the usual satisfying meaty thump of violence perpetrated and repaid. We don’t see any of the torture to Lucie; the film starts after she escapes. As a result, we don’t know who did what to her…and when she tracks down the people who she says are the perpetrators, we don’t know whether to believe her. As a result, we don’t get the rush of revenge. Instead, we see our putative protagonist perform a cold-blooded, motiveless murder of a normal middle-class family, including their high-school age kids.

We do find out later that the mother and father (though not their children) were the abusers…but by that time the emotional moment is lost. We don’t get to feel the revenge. On the contrary, no sooner have we realized that they deserved it, than we swing back over to the rape. Lucie has already killed herself, but Anna, her friend, is captured and thrown into a dungeon, taking her former companion’s place. There she is tortured by an ordinary looking couple who look much like the couple Lucie killed. Thus, instead of rape/revenge, we get the revenge with no rape, and the rape with no revenge. Violence is not regulated by justice or narrative convention; it just exists as trauma with no resolution.

I wouldn’t say that Martyrs is a perfect film, or a work of genius, or anything like that. Anna’s torture is done in the name of making a martyr of her; the torturers believe suffering will give her secret knowledge. And, as Charles point out, they end up being right — Anna does attain some sort of transcendence, a resolution which seems to justify the cruelty. And then there’s the inevitable final, stupid plot twist, when the only person who hears Anna explain her secret knowledge goes off into the bathroom and shoots herself. So no one will ever know what Anna saw, get it? Presumably this is supposed to be clever, but really it mostly feels like the filmmakers steered themselves into a narrative dead end and didn’t know how to get out.

Still, I think Charles is a bit harsh when he says that the film is meaninglessly monotonous, that it is not transgressive, and that the only thing it has to offer is to make the viewer wonder “can I endure this? can I justify my willingness to endure this?” Or, to put it another way, I think making people ask those questions is interesting and perhaps worthwhile in itself. It’s not easy to make violence onscreen feel unpleasant; it’s not easy to make people react to it like there’s something wrong with it. Even Charles’ demand that the film’s violence provide transgression — doesn’t that structurally put him on the side of the torturers (and arguably ultimately the filmmakers), who want trauma to create meaning?

Charles especially dislikes the handling of the high-school kids who are killed by Lucie. He argues that they are presented as innocent, because their lifestyle is never linked to their parents’ actions. Anna’s torture is mundane enough and monotonous enough to recall real atrocities, and conjure up real political torture — basically, a guy just walks up to her and starts hitting her. But the evocation of third-world regimes, or even of America’s torture regimen, no matter how skillfully referenced, falls flat since it is is not brought home to the bourgeois naifs who live atop the abattoir.

Again, though, I think the disconnection, which seems deliberate, is in some ways a strength of the film, rather than a weakness. Violence isn’t rationalized or conventionally justified in Martyrs — except by the bad guys, who are pretty clearly insane. In a more standard slasher like Hostel, everyone is guilty,and everyone is punished. In Martyrs, though, you don’t get the satisfaction of seeing everyone get theirs, because scrambling the genre tropes makes the brutality unintelligible. The conventions that are supposed to allow us to make sense of the trauma don’t function in Martyrs — which makes it clear how much we want violence to speak in a voice we can understand.