The first we see of Ryan Gosling, he is shown flexing his hands and squinting with terrific meaning before a statute of a strapping, shirtless boxer, and this, one suspects, is pertinent to why every critic in the world hated Only God Forgives.

I exaggerate, of course. A glance at any popular review aggregator will reveal a modest selection of minds sympathetic to this latest picture from popular Dane Nicolas Winding Refn, whose previous feature, 2011’s Drive, was met with a lingering rapture so disproportionate to its derivative pleasures — seriously, just sit down with Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man for two hours and you’ll get basically all of Refn’s deeper thematics, plus a stellar turn by Peter O’Toole — the observant reader can’t help but catch a whiff of guilty score-settling, or at least the unmistakable grimace of an indulgent teacher left embarrassed by a prize pupil’s misbehavior.

These are good concerns, because this new film is all about authority, and behavior, and guilt.

But before we get to that, I must make a personal confession. Absolutely critical to my experience with Only God Forgives was the realization that it is deliberately mistitled. There is, in fact, no English-language title displayed on screen during the opening credits; instead, the title is a Thai phrase, written in Thai script, which merely translates to “Only God Forgives” via subtitles at the bottom of the frame.

Moreover, it soon turns out that quintessential Hollywood hunk Gosling is not, in fact, the film’s hero, but an arguable co-protagonist with Thai actor Vithaya Pansringarm, whom not a few viewers of the original red band trailer mistook for the story’s villain – as perfect a coincidence as those (over-)sensitive to western exceptionalism could possibly dream!

Or did writer/director Refn plan it all that way? It seems unlikely – and not just because I have no idea who cut that trailer. Supposedly, pre-production on Only God Forgives began in 2009 with a much more traditional action movie scenario, but Refn — having subsequently overseen the mutation of Drive from a purportedly more ‘normal’ crime thriller to its languid final form — re-thought the picture as a moody, ‘foreign’ thing, eventually rolling with production crises to further that impulse: a lack of English-capable local actors resulted in a *lot* of subtitled Thai-language dialogue, and the absence of money for a soundtrack of American tunes inspired a recurring device of Thai characters performing domestic songs via karaoke.

That’s right. There’s three song sequences in Only God Forgives; three less than the average Telugu film, yes, but divvied out at similarly well-spaced junctures, as are the surprisingly modest action scenes. Did you know Refn once authorized a no-budget Hindi-language remake of his debut film Pusher, by a British filmmaker with an eye toward appealing to Indian audiences? This too got me thinking.

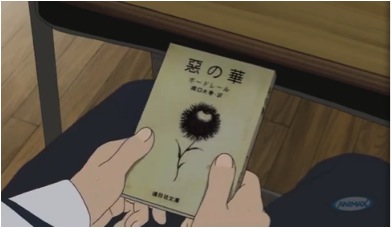

Having watched anime from a young age, I am accustomed to feelings of embarrassment. All around you in that peculiar fandom, at all times, is a strange fetish for marginal aspects of a foreign culture, or snatches of culture marginalized by their use: honorifics (mis)applied as a signifier of ‘understanding,’ weird debates over the accessibility of translation, and — since I knew mostly men — desperation-laden desire for an exoticised notion of female perfection, apparently native to Japan. This is not to say that some fans didn’t eventually develop a sophisticated understanding of language, culture and dubiously popular entertainment, but many more remained ignorant of their tourism, convinced instead that the meager abridgement of cultural engagement that is buying (or stealing) shit elevated them above the rabble, away from the debasement of American things and toward a verily rising sun.

I feel much the same way watching Indian movies today, though I am cognizant, of course, that a movie does not care who is watching. Like any single-screen front-bencher settling in for an evening of straightforward masala, I am invited to cheer the swaggering cop heroes and delight in the beautiful women, though I know that, fundamentally, part of my interest will always be the novel character of entertainment not exactly tailored toward a thirty-something heterosexual white American middle-class male, as is a good deal of the U.S. product which more and more seeks to dominate the filmgoing experience of international audiences as a valuable supplement to its already considerable returns.

Guilt, guilt, guilt. Need I mentioned I was raised stolidly Catholic? I do so wonder about Nicolas Winding Refn.

The plot of Only God Forgives concerns a murder of frustration, and the waves of incrimination that radiate outward in the manner of a stone dropped into a lake. The stone, in this case, is played by English actor Tom Burke, who is first spotted seething in a Bangkok kickboxing gym run by Gosling, his younger brother, as a front for the family’s lucrative narcotics smuggling trade. This is not deliberately a foreign expansion – Gosling had to be moved far away from America to escape a certain crime, and Burke, we might guess (though, like much in the film, we are not told), is supposed to be supervising him. Later, Burke skulks around the streets of the city, growling at a local pimp “I wanna fuck a fourteen-year old,” before offering the man an exorbitant sum for his young daughter. It is probably less a serious offer than a sneering display of the economic superiority that will always keep the locals polite, no matter how much it pains them.

Eventually, Burke secures the services of a prostitute, whom he then murders, for reasons which are never revealed, and perhaps unimportant.

Enter: Pansringarm, as a severe police lieutenant who observes only black and white moral distinctions. Instead of arresting Burke, he locks the white man in a room with the prostitute’s bereaved father, who pummels the killer’s skull into hamburger. Yet justice cannot end there, for the father too was a party to his daughter’s exploitation. The man pleads that economic and cultural circumstances led him to this place — he has no sons, which is financially disadvantageous — but because A is A, one of his hands is ceremonially cut off by Pansringarm’s righteous machete.

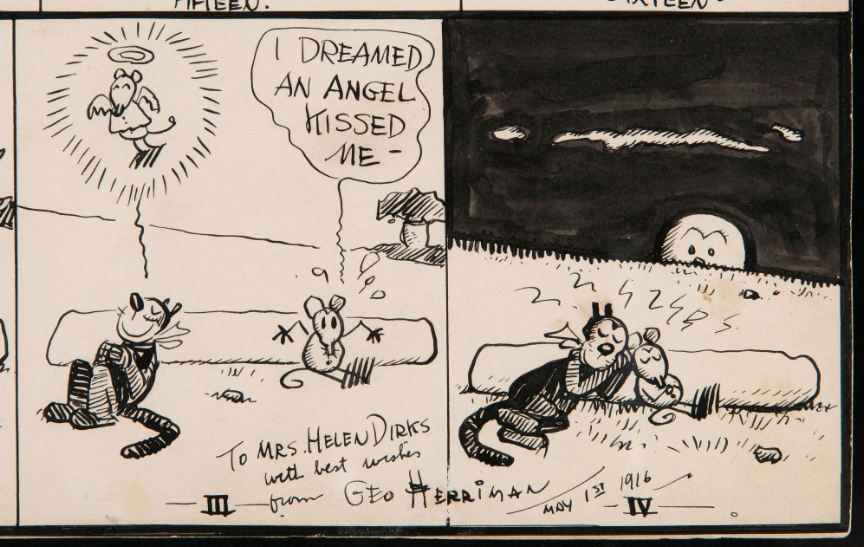

All of this Ditkovian melodrama is interspersed with images of Gosling staring at his own twisting hands, occasionally suffering precognitions of a confrontation with Pansringarm while wandering long, red-lined halls. He also fancies a local prostitute, though he seems disinterested in paying her to sleep with him – fantasies are crucial to Gosling’s life experience, and so he envisions his hands slipping up between her long legs, those instruments of violence depicted as, essentially, his primary sexual characteristic.

Alas, soon his wicked, wicked mother arrives from America, and Gosling — appalled at his brother’s actions and hoping things will remain settled — finds himself tempted into pursuing unenthusiastic vengeance against Pansringarm, turning those hands again… toward killing!

Pulpy material indeed, presented with a minimum of subtlety and maximal art direction, with a seemingly bottomless appetite for hoary visual metaphors. Flexing your hands in front of a statue of a boxer, washing your hands of illusory blood – by the time Kristin Scott Thomas’ malevolent mommy wraps herself around Gosling’s waist with her face pressed toward his crotch in commemoration of the Oedipal subtext at play, you can understand why connoisseurs across the globe dismissed this picture as the very definition of pretentious trash.

Still, I was utterly engrossed by the cultural dynamics central to the film. Put simply, all of the white characters are consumers, tourists, and their consumption is what causes much of the trouble for Bangkok’s luckless citizenry. Thomas contracts with an Australian fixer to assassinate the people who killed her son, an assignment then subcontracted to local thugs who shoot up the clientele of an entire cafe to get to Pansringarm, who himself then battles frightfully up the racial/class ladder until he has the white fixer pinned to his seat in a prostitution bar with needles plucked from ladies’ formal hairdos and flower arrangements, gouging out his eyes and gashing open his eardrums to relieve him of the senses he has misused.

The director is plainly thrilled by this old-school manliness, having once described his scenario as a ‘take’ on the great American cowboy films (though Bollywood movies too are full of heroic police who abuse due process to bring about Good); interestingly, though, the locus of manliness appears to have shifted from Gosling to Pansringarm during the film’s sequential shoot. You can easily picture him in a tall white hat, dispatching baddies without any angst. During the Australian’s torture, a theatrical police assistant urges all of the women in the club to close their eyes, while all the men are bidden to look closely, so they might appreciate the wages of sin. What showmanship!

Meanwhile, Gosling takes the prostitute with whom he is besotted to a fancy dinner attended by his mother, who proceeds to berate and humiliate the two of them in a fantastically vulgar manner, pausing only to turn to an off-screen waiter and order the table food. There is a certain ambiguity to exactly how much of Thomas’ absurd ugliness is occurring in Gosling’s imagination — and Thomas growls her dialogue with such lusty camp that she provides the film its sole source of comedy relief by virtue of performance alone — though plenty of external confirmation establishes her as a racist, grasping, misanthropic terror on her own terms, the kind of woman who perhaps sees a problem with what her older, departed son has done, in the abstract, maybe, but will inevitably choose the bonds of family over any exercise of empathy toward the funny local people who delay her activities through their broken English.

Outside, the prostitute expresses disbelief that Gosling would put up with such shit. Angered, the white man demands the girl remove the lovely dress he bought for her. She complies, standing proudly in her underwear and holding the fabric out toward Gosling, who is so ashamed he can scarcely reply.

Never have I seen an action-thriller so intimate with shame.

The ‘evil mother’ is a favorite character type of Alejandro Jodorowsky, to whom Only God Forgives is dedicated. And by this point in the plot, it is clear that Refn is sending Gosling out on a quest of spiritual and psychological evolution, as does Jodorowsky with so many lost souls. Santa Sangre — in which a man is maneuvered into violence by the specter of his mother guiding his *hands* — is a good reference point. Of course, to Refn, the idea of ‘evolution’ is to understand one’s true nature, like Gosling’s Driver in their prior collaboration, who is stunned to discover that he really is the super-cool expert killer he’d been playacting for so long.

But here, evolution terminates in annihilation.

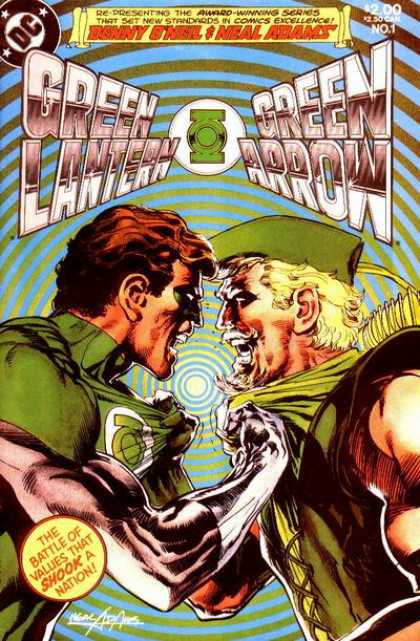

Only God Forgives, you see, is also reminiscent of Eli Roth’s Hostel series, in which tourists are ushered onto the next level of humans-as-commodities by their own bad behavior. But Refn does not characterize Pansringarm’s working class machete cop as himself an uncontrolled evil of capitalism; instead, he is unambiguously righteous, like a slasher movie’s killer cast as the hero, or a comic book avenger given a religious twist. Pansringarm himself has suggested a polytheistic reading of the character, positioning him as a literally magical “superhero” character, if but only one god among many Thai deities; Gosling’s situation, however, is specifically applicable to his domain, leading viewers of a certain religious disposition to inevitably conjure visions of a looming, Old Testament-style fire ‘n brimstone Gawd.

Politically, this is arguably problematic. Thailand’s recent history is marked by periods of military crackdowns on democratic activity, yet Refn places all of his enthusiasm in a brutal representative of Authority, one whose tolerance of prostitution/intolerance of individual prostitutes can easily be taken as advocacy for retrograde gender assumptions. No questions are asked by Refn – this is all necessary, one assumes, to combat the hellacious rudeness of capitalistic white condescension, of which Gosling, try as he might, cannot wriggle free.

Yet Refn knows he himself cannot do it either.

***SPOILERS FOLLOW***

In my addled little head, the act of Refn’s filming a movie in an exotic foreign location, for occidental delectation, became a metaphor for consuming foreign entertainment. Gosling is the ‘good’ consumer, looking to forge real relationships with women, respecting local performers/athletes, not murdering anyone, etc. But he learns, gradually, that he is still implicitly in the position of abuser, unable to escape the dread orbit of his mother; he cannot really accomplish terrific feats with his hands, and he is impotent as a lover – it is exactly the reverse of Drive, the bloody fantasies of which were so loved.

Inevitably, it comes to pass that Gosling asks Pansringarm for a fight. The powerful cop absolutely destroys Gosling, who doesn’t land so much as one punch, leaving the room with his pretty Hollywood face rearranged into a monster makeup mosaic of bruises reminiscent of Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tokyo Fist. The climax of the movie quickly follows. Pansringarm confronts Thomas, who reveals that Gosling murdered his own father, and suspected her and older brother Burke of having an incestuous affair. Not one to abuse his emotions, Pansringarm cuts her down.

Intercut throughout is Gosling’s own attempt to track and kill Pansringarm at his home. Too late, Gosling realizes that his backup thug has orders from Thomas to murder not only Pansringarm, but his wife and young daughter. The white man stands still as the woman is shot dead, but he acts in time to prevent harm from coming to the little girl, who in an earlier scene expressed to her daddy an interest in people solving their problems by talking them out. In a Christian sense, she is the peaceable [Son] to Pansringarm’s wrathful Father, and she stares silently at Gosling while he departs, as proud and stoic as the prostitute he shouted at, perhaps having already forgiven him.

Doubtlessly, many viewers will expect the film to conclude with a final battle between crook & cop; they will have to content themselves with memories of Albert Brooks’ stabbing. Gosling discovers his mother, slices open her womb, and fiddles around inside, perhaps eager to return; this could be the ultimate goal of his incestuous urge, to be like a child again, and not care about anything. This is futile, so he goes again to pay and watch his favorite prostitute, who can’t entirely get rid of him so long as he has money.

Pansringarm meets him there.

Gosling imagines they are in a field.

The white man offers both his hands in penance for his and his family’s sins.

Only God Forgives.

And then we are back in the karaoke bar, where Pansringarm takes the stage to sing the song from that original red band trailer. There are no white people in the theater. The lyrics are not translated; it is a communication Western audiences will not understand. The dream of obliteration is realized. Closing credits are displayed over the performance, again in Thai script, but with English translations now provided just below each name, instead of out of the frame. Hope remains, at least, for the future.