Jean-Luc Godard’s 1964 film Contempt inventively deviates from cinematic convention and probes gender relations while it explores miscommunication between people. The storyline is loosely adapted from a 1954 novel by Alberto Moravia, Il Disprezzo [A Ghost at Noon) and depicts the production of a film-within-a film, a cinematic version of Homer’s classic Odyssey. Multileveled ambiguities complicate the narrative of the movie enough that many writers have misinterpreted Godard’s premise. They fail to understand why the female protagonist becomes disillusioned with her husband. I will interrogate those critical misapprehensions to suggest another reading of her response. I will further attend to a sequence that is rarely mentioned in the copious literature about Contempt. The scene in question is a mise en abyme staged in a movie theatre auditorium, which displays in microcosmic form the primary deconstructive and reflexive techniques of visuals and sound that Godard uses throughout the film. In that scene, through a critique of the dominant ideologies of Hollywood and by exploring male and female relations, Godard reveals how women are diminished.

In an interview done while he was working on the film, Godard reduced the plot down to one simple sentence: “It’s the story of a girl who is married to a man and for rather subtle reasons begins to despise him” (Feinstein, 9). This quote indicates that the director considers the primary theme of the film to be the disaffection of the couple, with a particular focus on the feminine rationale; however, the way in which Godard reveals the response of a woman to her husband’s behavior is far more complex.

The narrative can be more properly synopsized as follows: a young writer, Paul Javal (played by Michel Piccoli), is commissioned to write a screenplay for a filmed version of Homer’s Odyssey, which is to be directed by Fritz Lang, who plays a version of himself. The film is financed and produced by an extremely arrogant American, Jerry Prokosch (played by Jack Palance), who cannot speak the languages of those involved in the film production, but relies on his assistant/interpreter Francesca (played by Giorgia Moll). Prokosch’s demands strain not only the progress of the film, but also Paul’s marriage. The writer takes out the brunt of his frustrations on his wife Camille (played by Brigitte Bardot) and he uses her to curry favor with the producer, which eventually leads to the separation of the couple and her death.

When Contempt was first released in 1963, it was the most widely promoted and renowned of Godard’s films and indeed, of any film connected with the French New Wave. A huge literature has built up around the film in the time since its release and a newer burst of analysis occurred after the release of the Criterion Collection DVD in 2002. However, many of the critics that have been written about it, both at the time of its release and more recently, seem to have misread the reasons why Camille leaves the callow, compromised writer Paul, to go with the crude and bullying American producer Prokosch. This confusion is in spite of, or perhaps due to, the fact that so many writers have dismissed the importance of Godard’s story content. They echo the commentary in David A. Cook’s textbook, A History of Narrative Film: “The narrative portion of Le Mépris, which concerns the dissolution of the scriptwriter’s marriage, is less important than Godard’s use of the self-reflexive conceit” (542). Cook’s claim results in a distorted view of the film because he privileges Godard’s reflexive techniques over the content of his narrative. In fact, the nature of Godard’s practice is such that the representations and socio-political content in his narratives are every bit as important as the cinematic forms of depiction that he uses. They are intricately and essentially bound together. Godard is always self-reflexively pointing to the way the film industry and his personal life are tied together and how representations inform the relationships between men and women.

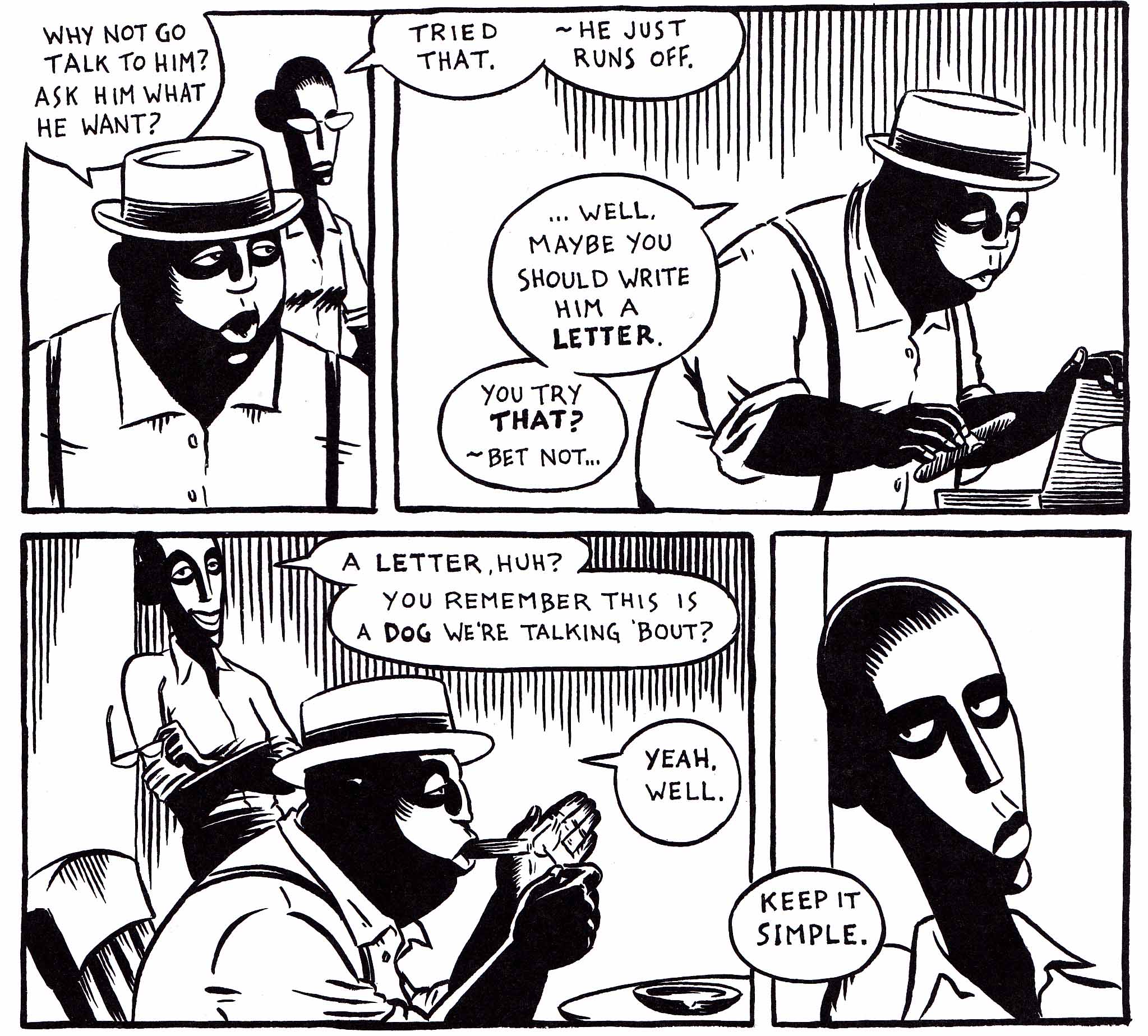

Alternatively, the cinematographer of Contempt, Raoul Coutard, remarked that the director made the film to be a “million-dollar (love) letter” to his soon-to-be-ex-wife Anna Karina (Horton, 210). Seen in this light, Contempt is Godard’s self-analysis of certain of his own negative behaviors, which by explicating them in the course of the story, he acknowledges to have contributed to the eventual dissolution of his marriage. Therefore, the film is rather a confession or apologia, than a love letter as such. There is a high degree of personal investment in the narrative, which shows that that narrative should be accorded the same level of critical attention as the technical aspects of the film.

Many have said that the success of the film is largely due to the conspicuous presence of the famous beauty Brigitte Bardot in the cast. Her erotic presence and star power inform public reception. Likewise, veteran American tough-guy character actor Palance is used effectively as the American producer Prokosch. His casting incorporates the audience’s expectations, as noted by critic Robert Stam:

In the cinema the performer…brings along a kind of baggage, a thespian intertext formed by the totality of antecedent roles.(…) By casting Jack Palance as the hated film producer Prokosch in Contempt, the auteurist Godard brilliantly exploited the sinister memory of Palance’s previous roles as a barbarian (in The Barbarians, 1959) and as Attila the Hun (in Sign of the Pagans, 1959). This producer, the casting seems to be telling us, is both a gangster and a barbarian, a suggestion confirmed by the brutish behavior of the character (548).

Palance is so famed as a portrayer of gangsters, even to the French, that his presence in the film telegraphs “villain” to the audience fully as much as Fritz Lang indicates “venerated director” or Bardot indicates “sex kitten.” Palance and Bardot are both used reflexively within Contempt, as their extra-screen images carry meaning in very different ways into the narrative of the film. They each indicate stereotyping, or rather they reflect the traditional male and female characters that are produced for Hollywood narratives, but in Contempt they demonstrate how those stereotypes complicate real-world expectations.

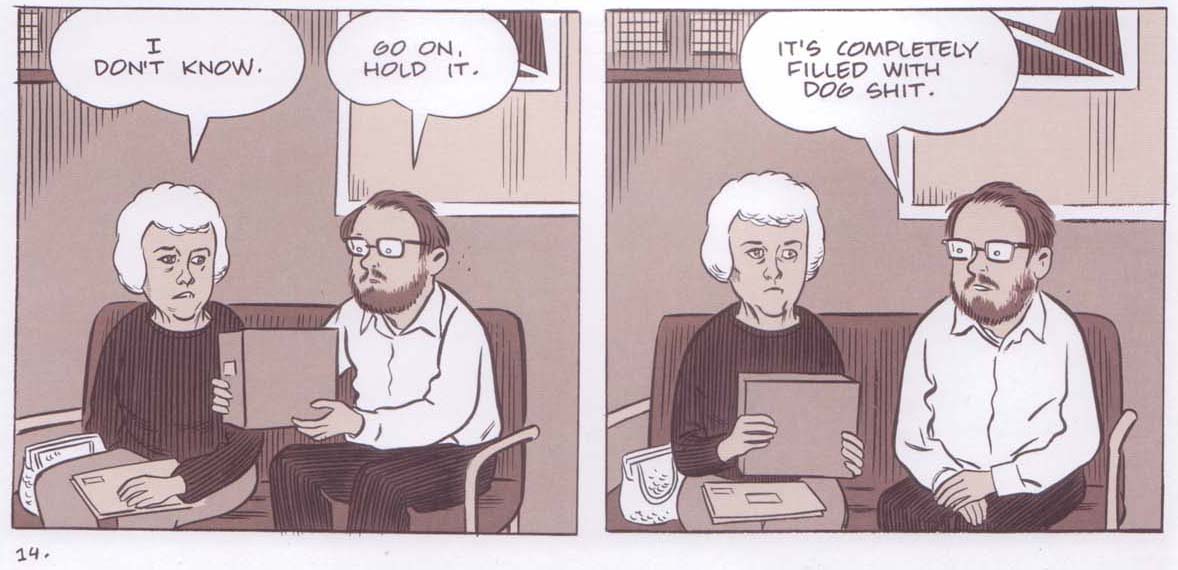

In fact, male/female relations are a central concern of Contempt. At a screening that Lang has arranged to show Paul and Prokosch rushes of the film in progress, the producer arrogantly makes claims to understand how “the Gods” feel, but then leers and sniggers in a degraded way at shots of a nude woman swimming onscreen. He forces his assistant and interpreter Francesca to bend over, while he uses her back as a desk to write a check buying Paul’s rewriting services.

Disturbingly, Francesca serves his efforts to control the film, since she is not only selective in how she chooses to translate Prokosch’s English words for the film team, but also, she edits what she relays of what they say back to him.

Stam also points out how Francesca chooses to perform her functions as translator: “(she)….mediates between the monolingual American producer Prokosch and his more polyglot European interlocutors.(…) Francesca’s hurried…translations invariably miss a nuance, smooth over an aggression, or exclude an ambiguity” (549). As will be seen to also apply to the other female characters, Francesca primarily is ventriloquized by the male characters; the words of Prokosch and the other male character are filtered through Francesca. She does not speak her own thoughts or opinions, but can only edit, at best. Francesca sometimes subverts her employer’s interests — when Lang frequently makes disparaging remarks about the producer in languages that Prokosch doesn’t understand, she often either mitigates them by altering their meaning, or doesn’t bother to translate them at all. However, her discretions regarding Prokosch’s proclamations and the responses they elicit are wasted on the multilingual Lang, at least, because he is aware of exactly what Prokosch is saying.

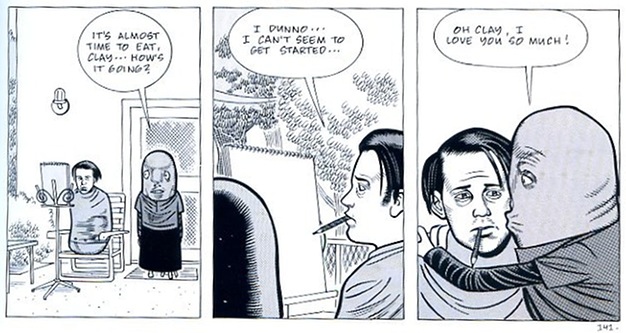

Many critics have wondered why Camille falls out of love with Paul in the course of the story For instance Colin McCabe says that he cannot see how Paul’s behavior can “explain [Camille’s] contempt for her husband, nor her decision to have an affair with Prokosch.” (155). McCabe misconstrues the reasons for the couple’s disaffection and blames it, as if by default, on the woman involved. This is a misreading apparently based on the spurious, sexist views of “liberated” female sexuality that were prevalent at the time the film was first released, rather than anything seen in the film. Significantly, Camille is traded like a commodity between Paul and Prokosch. Neither man cares about her opinion. Paul silences her and betrays her trust. He and Prokosch both attempt to remove her agency. This represents the way in which the dominant ideologies of Hollywood deprives women of their voices and uses them only for their physical beauty in films.

Despite any protestations Paul makes to Camille and to Lang in his consultations with the director, whose advice he seems to ignore, the writer goes along with Prokosch’s desires regarding the script he is supposed to be working on. In his behavior, Paul shows himself to be no better in his way than Prokosch is in his. It is notable that to curry favor with Prokosch, Paul repeatedly pushes Camille at the American. First, Paul arranges for Camille to ride with Prokosch in his sports car. It is the first major blow to the marriage. Camille is disgusted that Paul entrusts her to the care of such a man. Paul is then late himself in getting to where Prokosch drives her and he makes an unconvincing explanation for his tardiness. Francesca arrives at the destination on her bicycle belatedly and just after Paul, which gives them the appearance of collusion and we, the viewers, cannot say whether or not there is justification for such an implication.

Subsequently, Camille’s worst suspicions are apparently borne out when later, she enters the interior of the Capri residence to see her husband casually fondling the interpreter. Camille observes that Lang is also forced to work with Prokosch, but shows obvious contempt for the producer.

Throughout the film, Paul displays no ethical backbone at all. He whines to Camille and vacillates about whether or not to compromise his talents, as he is unquestionably in the process of doing just that. He has taken Prokosch’s check after the producer made a fool of himself in an absurd tantrum. Yet, Paul blames Camille for his compromises. He says he must do so in order to make more money to pay for the apartment that she likes. In his escalating argument with her, Paul condescendingly describes Camille as a “typist” who he has somehow elevated in status by his attentions, even though typing is the only activity we see him do.

Additionally, Paul has been hiding things from his wife that she subsequently discovers: that he is a member of the Communist Party and that he has a gun. In the extended apartment scene, the entire relationship slips over the edge when he unexpectedly, shockingly slaps her. She then says that she fears him and that “it wasn’t the first time either,” implying that he has physically abused her previously. Later, Paul pushes Camille on Prokosch again and insists that she leave with him on his boat while Paul remains behind on set. Paul later spies Camille and Prokosch kissing, and blames Camille.

Paul brings a gun onto the set for the purposes of threatening Prokosch, but he does not follow through, apparently because it would endanger his employment.

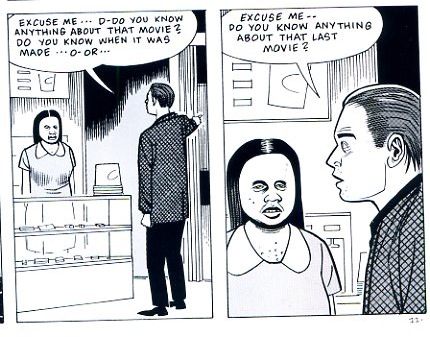

The auditorium scene (the chapter titled “7. An Audition” on the DVD) is rarely noted in articles and papers about Contempt, but it forms a microcosmic view of many of the most important themes of Godard’s innovative mise-en-scène. It can be usefully examined by splitting its elements into two parts: one that focuses on the visual aspects of the scene and one that concerns itself with Godard’s use of sound. The scene is staged in a movie theatre and/or auditorium that is being used for a casting call that is set up in the form of a dance performance.

____________________________________________________

Visuals

The scene in question is prefaced by another, much shorter scene that takes place in a cab. This short interlude links the very famous long take within Paul and Camille’s apartment to the scene under particular examination here, the casting call that takes place in an auditorium. After the emotional sequence in the apartment, Camille escapes in a cab, trying to leave Paul behind, but he runs to catch up to the vehicle and hops in. There is a brief interchange between the couple and then Camille apparently surrenders, to be taken to the casting call. Her anger and disgust at Paul is emphasized by the abrupt imposition of a dark filter over her image. This is one of several occlusions of Camille, which foreshadow what becomes of her at the end of the film and also echo the use of colored filters in the nude scene at the beginning of the film.

In the present scene, the dark filter leaves only the silhouette of Camille’s head and the whites of her eyes visible, whites which glitter strangely. The filter simulates a temporal passage from daylight to early evening, but it also represents an occlusion of the character of Camille. The darkening, taken with the swelling at that moment of the non-diegetic score, symbolically predicts her fate at the end of the film.

Inside the theatre, the girl onstage mimes a pop song as she dances in an eroticized manner, wiggling her hips and shimmying from left to right and vice versa. The other performers behind her onstage simply walk in male/female pairs from one side of the stage to the other, only to turn and walk back again, repeatedly. One of the couples separates as a woman goes offstage; her male partner then wanders back and forth among the other couples as if confused. They are all shot with sweeping back-and-forth horizontal movements of the camera. This is similar the other slowly swiveling horizontal pan shots in this film, but in this case the actors have their lower legs and feet cropped out.

Their movements become groundless and their shifting figures seem to be sliding in different directions, which creates a dizzying, unmoored sensation in the viewer. Simultaneously, the shadows of the performers project via multiple light sources onto the movie screen behind them and above the stage, replicating their images in ghostly overlays and reflexively emphasizing the nature of film itself, as 2-dimensional images representing 3-dimensional reality, created by projected light. The lead dancer lip-synchs the song while she dances with occasional odd high-stepping leg movements, as if pulling to extricate her legs from a mire.

When the view reverses to show the audience and the production team in the auditorium, again with slow, to-and-fro horizontal pans, Lang and Camille are on the left side of the aisle. Camille speaks to Lang and they exchange private gestures of disgust about those on the other side of the aisle, but we cannot hear what she says. Francesca is behind them, reading a newspaper and translating for Prokosch, so she is heard, but she is often blocked from view. On the right side of the aisle, Paul sits with Prokosch, who eventually rests his arm on Paul’s shoulder in an overbearing manner that implies Paul is simply furniture. A photographer repeatedly emerges from behind Paul and Prokosch to crouch in the center of the aisle and shoot pictures with a flashbulb of what is transpiring onstage (aiming towards the fourth wall that separates viewer and film).

As they are leaving, Prokosch crows that he has convinced the singer to appear nude at a later shoot. This resonates with the major demand made on Godard by one of the real producers involved with Contempt, the American Joseph Levine, that a nude scene of Bardot be added to the beginning of the film. Godard managed to turn this compromise to his advantage by making that scene work beautifully and support his narrative. However, that was not Levine’s desire. He just wanted Brigitte Bardot naked in the film for commercial reasons. In Hollywood, even such a star as Bardot is only there to stimulate the erotic desires of a male audience. Sex sells; it is the basis of the economy of cinema. At the end of the scene, the film team goes up through the aisles of seats while discussing the actors’ roles within the adaptation of Odyssey. Camille rejects Paul’s conciliatory efforts, but reserves a smile for Lang when he cites her (Bardot’s real) famous initials, “B.B.” Camille then removes herself from the group to pass through an upper row of seats, separated from the others. Prokosch moves ahead and reaches the exit first; he then turns, dramatically placing one leg up on the seats at the end of the row Camille is navigating. When Prokosch asks Camille why she doesn’t speak, the theatre lights are cut and she is again plunged into darkness, one not quite so deep as that which enveloped her in the preceding scene in the cab, but echoing its affect. The shadow around Camille obscures her and reduces her to just a shadow, as she reiterates her muteness.

____________________________________________________

Sound

The sound of the scene is also key to deciphering its reflexive narrative qualities. Camille and the “singer” onstage are depicted as voiceless, sexualized bodies. Francesca is also voiceless, but in a somewhat different way; she functions as a mediator and such limited agency as she has is limited to withholding small bits of information. These characters symbolize the roles forced on women by Hollywood that relegate them to a lower class. Women may perform, but words are put into their mouths by men and their acting roles are most often passive and subservient—they may be mothers, homemakers, servants, secretaries or sex toys. They may mediate between men or be traded as commodities among men, but whenever possible, their proactive participation in the power structure is avoided by the male-dominated film industry, then and often still.

As previously noted, in the taxicab sequence that links the famous apartment scene to the auditorium scene, as Paul forces Camille to accompany him to the audition, a filter darkens the image of Camille as the non-diegetic Moravia score swells up portentously. In this way, visual and auditory cues influence the viewers to ascribe great significance to the obscured image and dramatic music–which with hindsight, appear to foreshadow what will become of Camille as the movie’s events unfold. Then, the scene cuts to the approach to the auditorium.

The team working on the film of Odyssey is at the theatre to watch a casting call occurring on a stage in front of a large movie screen. A “singer” who is not actually singing dances onstage in front of a “dancing” troupe made up of couples who hardly dance. Because there is no alteration in the volume of the lead vocal of the song as she shimmies and slides far past the microphone in either direction, it becomes clear that the woman is lip-synching to a recording. One wonders what role she could be cast for then, since she is just a body, an apparent “speaker” for the music with no voice of her own. The diegetic music is murky, brassy and too loud for the auditorium’s audience to have a conversation over.

However, when the view reverses to show the audience, the diegetic music cuts abruptly so that the conversation of the main characters, seated in the front rows of the audience, can be clearly heard. Harun Farocki explains the significance of this device within the greater arc of the director’s filmed corpus: “…it is Godard’s way of comically obeying a rule of sound mixing which he almost always breaks: the rule that ‘background’ noises should be lowered during conversations” (Farocki & Silverman, 49). Farocki understands how Godard alerts the viewer to the ways in which sound is typically presented, in order to demonstrate its artificiality.

In the commentary track included on the DVD, Robert Stam also finds the reflexive manipulation of the sound of this scene comical. However, what is revealed of the characters in the conversations that become audible because of the dropout of the diegetic music is anything but amusing. Both Lang and Camille display revulsion primarily through miming, each for their own very good reasons. Francesca must mediate between the male parties and Paul sulks, but continues to acquiesce to the crass Prokosch’s ongoing bullying.

Two online commentators who reviewed the more recent DVD release of Contempt have opposing views of the sound in this scene. Glenn Erickson takes the scene to represent a theatrical presentation; he misunderstands the purpose, which is actually that the characters are attending a casting call, but he points to the deliberation of the sound techniques that Godard used:

When the leads attend a typically artificial and unconvincing theater performance, Godard takes the opportunity to deconstruct the movie making process. A ‘slotted’ playback tape is used, to which the supposedly live singer on stage lip-synchs. The audio crew has spliced specific holes of blank tape into the playback reel. The appropriately timed gaps of silence allow the spoken dialogue to be recorded in the clear. It’s a standard musical technique, I saw it used on the big dance number in 1941. But here in Contempt, instead of remixing the scene with clean, uncut music, Godard leaves it raw. The jarring holes in the playback punch in and out, making the scene purposely artificial, unfinished…anti-slick (Erickson).

Even as Erickson misses the narrative point of the scene, he apprehends the technical innovations involved. Godard even has the sound cut-off occur within a single shot. For instance, as the film team is shown, the music is heard, then drops out so we hear the conversation. Then the music resumes before the camera shows the stage. In this way, the director draws the viewer’s attention to the various multi-levels of narrative taking place and the fact that the conversation could not be heard unless the music was muted.

Joshua Zyber understands what transpires in the scene, but he treats the director’s handling as negative and possibly accidental:

Like most of the director’s films, Contempt is filled with pretentious attempts to play with or deconstruct the language of cinema. (…) An overbearing score often drowns out the dialogue. During a scene in which Jerry auditions singers, the music and singing abruptly cut out on the soundtrack whenever the main characters speak (Zyber).

Whether or not Godard’s work is “pretentious” is debatable, but his effects are entirely deliberate. As Zyber notes, the music does “drown out” the dialogue in other scenes, but in this scene, the music drops out whenever Prokosch, Francesca, Lang, or Paul speak.

They sit in the front row, first Lang beside Camille, with Francesca seated in the row behind them, and then across the aisle, Paul besides Prokosch, who pontificates while Francesca translates. Francesca has no authority or agency; her words are never truly her own, although she occasionally edits her translations in the interests of diplomacy. Rather, she is a conduit between men, she is a body used for transmission. Often Francesca can’t even be seen; her positioning makes her invisible, a disembodied voice that has no apparent source. Her skills as a linguist or mediator are never acknowledged and she is never thanked by those that she serves.

Camille seems to be primarily there as an erotic presence. She is not actually part of the production and she hardly speaks while they are seated. When she does, it is overridden by the diegetic music. Paul speaks to her, but she doesn’t answer him back. Several times, she gestures as if she is exchanging words with Lang, but she cannot be heard. As they leave the auditorium, the party continues to discuss the movie project. Paul attempts to speak to Camille, only to be angrily but silently rebuffed. Lang is reflexively faux-ventriloquized by Bardot, as he ascribes a Berthold Brecht quote to her nickname “B.B.” This reference seems to prompt Camille to soften for a moment and silently smile. Lang then specifies those initials as signifying Berthold Brecht, another reflexive touch.

Prokosch makes an announcement regarding the arrangement he has made with the singer: “She agrees to take off her clothes, Tuesday morning, 8 o’clock on the beach” (ironically reflecting the demands made on Godard and Bardot by the real American producer of Contempt). Again, the singer’s voice isn’t heard, her words are only mediated through Prokosch. As the group traverses the aisle on the way out, Prokosch says in English to Camille, “Why don’t you say something?” As Paul and Lang both turn to look at her, a loud click is heard and the lights of the auditorium come down. Camille is eclipsed in shadow as she looks up at the stage and answers (according to the subtitles), “Because I’ve got nothing to say.” This indicates that as with Lang, Camille also understands English and so is more aware of the significance of the various conversations and manipulations occurring around her than she lets on.

According to Kaji Silverman and Farocki Harun, Camille’s silence reflects her symbolic role within the Homeric allegory that the film represents:

HF: …Camille is the only one of the four major characters who never offers a verbal interpretation of Odyssey—the only one who makes no claim to stand outside it, to relate to it from a distance.

KS: Instead, she accepts her preassigned role from the start, and simply persists in it (50).

This interpretation implies that Camille-as-Penelope is locked into a voiceless role, a view echoed by the singer onstage, who is also voiceless in her lip-synching, who pulls yet cannot extricate herself from the cropped-off, boundless space of the stage and who will also soon enough be stripped bare by Prokosch for his pleasure. Similarly, Francesca has no real voice of her own; she merely parrots for the men more palatable versions of their words to each other.

____________________________________________________

Throughout the film, Paul emotionally and physically abuses Camille whenever he has a chance to address her without anyone else seeing. It is his violence, his shallowness and his lack of integrity that drive her away. And the result of all of Paul’s betrayals, compromises and rejections is the worst possible one for Camille: Prokosch is eventually the death of her. In the end, after Camille leaves Paul, she and Prokosch are killed in an automobile accident.

Camille’s death at the end of the film is also misconstrued by some Godard scholars, such as Douglas Morrey, who says it “appear(s) as distinctly arbitrary and as such, it is difficult not to conclude that Camille is being punished for her actions, and punished indeed for her gender which appears solely responsible for those actions. The sudden death at the end of Le Mépris has no generic or narrative motivation….but nor is it realistically motivated…” (20). But a conclusion such as this seems again to reflect preconceptions on the part of the critic, rather than observation of the events depicted in the film. Camille makes no actions that are not precipitated by Paul’s inexplicably cold, contrary and even abusive behavior.

Few Godard scholars misread Contempt as offensively as does Jeremy Mark Robinson. At the outset of his examination, Robinson writes:

Contempt is a film about Brigitte Bardot’s ass (and a very nice, smooth rounded ass it is too). Bardot’s butt is the super special effect, the mega-buck production value item at the heart of the film. The writer Paul quips in the film that if you show a woman a movie camera, they’re happy to show off their behinds. Contempt demonstrates that, time after time. It’s a film of what Godard called the “civilization of the ass” (161).

Here Robinson attempts to ascribe his own sexism to Godard. But in his quoted comment as well as in his self-reflexive movie, Godard alerts the viewer to the absurdity of the patriarchal film industry, to the idea that the producers are self-important, tasteless “asses” who, ironically, are apt to align themselves with Robinson’s literal interpretation. Robinson says of the initial nude scene with a similarly derogatory tone:

The lengthy shot…frames Bardot’s back and buttocks and legs, cutting out the heads of the couple, and the film will do this a number of times, as if telling the viewer, no, you’re not really interested in faces or what the people are saying, you want to see Brigitte Bardot’s naked body. The instinct of the (sic) Contempt’s producers was spot on, of course. And Godard was happy to do what was asked (167).

Again, Robinson assumes wrongly that he comprehends Godard’s motivations and is qualified to judge his integrity. These quotes instead indicate the depths of the critic’s misogyny and his condescension to the audience.

More reasoned is the description by Colin MacCabe:

…there can be little doubt that Contempt would be a much less beautiful and moving film without the long opening scene of Bardot naked on a bed. This highly stylized scene, both in the repetitive naming of the parts of the body and in the use of very strong primary colour filters, delivers neither the pornographic charge nor the psychological explanation which Levin wanted. It does, however, provide perhaps the most beautiful portrait of Europe’s most photographed woman and a hint of the married bliss which will turn to catastrophe in the course of the film (154).

McCabe appreciates how Godard satisfied the producer’s demands while simultaneously subverting them, no mean trick. As a result, the film can sustain a feminist reading of its depiction of an abusive relationship even as it plays on its status as a star vehicle for one of the most objectified of actresses, Brigitte Bardot. Even by the values of 1963, it should be seen that it is Paul who is as Camille says, “an ass.”

A large part of the shock value of the film is watching a man callously maltreat his wife, as Paul does; the abuse is emphasized in seeing it happen to a character played by the famously desirable Bardot. Her various close-ups, even when subversive in content, still achieve exalted heights of glamour and help to propel the film to legendary classic status. In one profile shot that echoes the painted statue sequences that are interspersed through the film, Camille speaks a transgressive list of obscene curses, then turns and her face crumples in pain. In another close-up, she nurses her burning, slapped cheek.

Despite the actress’s engagement in her role, the character of Camille is as much the intoxicating Bardot as “Lang” is Lang. Godard’s ability to play on this adds to the reflexivity of the film in many overt and subtle ways. In her bathtub scene, Camille reads a biography about Lang, and quotes his words. Lang in his role as himself speaks lines that express Godard’s own theories. And, as noted earlier, in the auditorium scene, Lang quotes Bardot’s ubiquitous nickname “B.B.”

Even as Godard embeds in his film specific depictions of how creative people are used and abused by the money interests of Hollywood and other players in the commercial movie world, he shows how women are specifically maltreated and exploited within that system. Godard pulls aside the curtain on the private emotional interactions between men and women, to expose and comment on the shallowness of male sexism and weakness of character. He shows how relationships can be dismantled through one partner’s realization that their love has been taken for granted, or that their sexuality has been exploited for the purposes of career advancement, or by a victim’s rejection of escalating mental and physical abuse. In this way, Godard makes a classic film, yet one that destroys the artifice of film. Contempt raises questions about female agency and the female voice. It points to problems which it does not answer, but at least Godard notices that the problems exist. He made Contempt to be derisive in tone, towards a society that rewards sexism and cruelty and towards the processes of filmmaking that demand so much compromise from artists.

____________________________________________________

Bibliography

Contempt (Le Mépris). Dir. Jean-Luc Godard. Perf. Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance. Criterion Collection, 2002. DVD.

Cook, David A. A History of Narrative Film. 3rd Ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996. Print.

Dixon, Wheeler Winston. The Films of Jean-Luc Godard. State University of New York Press, 1997. Print.

Farocki, Harun and Kaja Silverman. Speaking About Godard. NYU Press, 1998. Print.

Erickson, Glenn. “DVD Savant review: Contempt”. 5 Dec. 2002. Coolector Movie Database. 15 March 2013.

Giannetti, Louis. Understanding Movies. 8th Edition. N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1999. Print.

Godard, Jean-Luc. Interviews. Ed. David Sterritt. University Press of Mississippi, 1998. Print.

MacCabe, Colin. Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70. UK: London: Bloomsbury, 2003. Print.

Morrey, Douglas. French Film Directors: Jean-Luc Godard. UK: Manchester University Press, 2005. Print.

Robinson, Jeremy Mark. Jean-Luc Godard: The Passion of Cinema. UK: Kent: Crescent Moon, 2009. Print.

Stam, Robert. “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation.” Film Adaptation. Ed. James Naremore. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000. Print.

Temple, Michael, James S Williams and Michael Witt. Forever Godard. UK: London: Black Dog, 2004. Print.

Zyber, Joshua. “Contempt (Le Mépris) (Blu-ray)”. 22 Feb. 2010. Hi-Def Digest. 15 March 2013.