Part 1: What Is A Fight Scene?

Fighting is to superhero comics what fucking is to pornography, or singing to musicals: the raison d’etre, the sine qua non, the whole kit and kaboodle. It’s why skeevy guys creep around in trenchcoats with a box of tissues, bottle of lube, and a very special life-sized doll named Candy; or why other people watch porn or musicals.

All three genres demand that character, motivation, theme, incident and conflict be expressed in distinctive forms. In musicals, it’s song; in porn, it’s, well duh; and in superhero comics, intra- and inter-personal conflict above all else must be expressed and resolved through physical conflict. In other words: the fight scene.

Few cartoonists have understood this more than Jack Kirby, whose superhero comics, especially from the 1960s and onwards, are positively drenched with fight scenes. We can see this by comparing Kirby’s 1960s work for Marvel with some roughly contemporaneous superhero comics published by Marvel’s chief competitor, DC. Take, for instance, the Superman comics produced by Curt Swan, Kurt Schaffenberger, Wayne Boring and others, under the tyrannical editorship of Mort Weisinger. There are vanishingly few fight scenes in these comics; Superman himself rarely gets to punch anything, which makes a certain kind of sense — since he is, after all, essentially invulnerable and nearly omnipotent, how could he possibly get into a fight that lasted more than three panels?

Panel one: bank robbers running out of Metropolis First.

Panel two: Superman swooping down to punch them into submission.

Panel three: Metropolis’ streetsweepers and janitors scrubbing splatters of brain and flesh off the street.(1)

It’s surely no coincidence that, of Superman’s cast of recurring villains, only a handful are memorable, and of those, two are defined entirely by their intellect — evil scientist genius Lex Luthor and evil alien genius Brainiac (!).

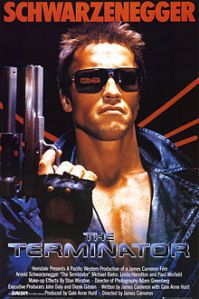

By contrast, the superpowers of many of Kirby’s chief 1960s characters are desultory, a thin excuse to motivate fighting, fighting, and more fighting. Consider: Thor is a strong guy with a hammer that he uses to beat the crap out of people. Captain America is just a normal guy (more or less), with a shield that he uses to beat the crap out of people (2). The Hulk is a strong guy with a, well, he just uses his own fists to beat the crap out of people. The Hulk’s whole power just is beating the crap out of people.

But we can say a little more about the visual logic of superhero comics than just “there is one”, and we can do so by thinking about the structure of a fight scene as abstractly and generally as possible. For what, exactly, is a fight scene? A scene with a fight, of course, but what does that actually mean? At the most abstract level, we can conceptualise a fight scene — in the narrow genre of superheroes, or any other kind of comic — as a sequence of aggressive or defensive actions and their effects — more precisely, a fight scene is

a sequence of events caused by the aggressive and defensive (and other) actions of two or more combatants

This needs some unpacking, so I’ll take you through it, in reverse order.

of two or more combatants

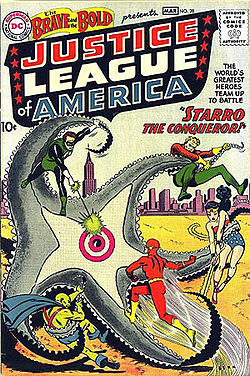

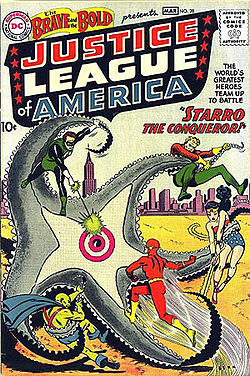

the Justice League battle Starro the giant starfish, from Brave and Bold #28 by Mike Sekowsky

The participants in a fight scene can be people, but they can also be animals, robots, zombies or anything else that can act — that can take action of one kind or another. In the simplest case, we have just two participants fighting, but superhero fight scenes — particularly so-called “team books” like The Avengers or Justice League of America — routinely feature three or more combatants. Where there are more than two participants, they can be distributed in any number of ways; that is to say, it could be one versus two, one versus three, two versus two, two versus one versus one… In principle there is no upper limit to how many combatants can participate in a fight scene, but in practice there are vague limits imposed by constraints like the size of a page, the quality of reproduction in printing, and the reader’s (and the artist’s!) patience.

events caused by the aggressive and defensive (and other) actions

In a fight scene, at least one participant is trying to damage, somehow or other, at least one other participant, who may be trying to damage the other in turn, or to flee, or merely to avoid damage, or to do any number of other things (but usually one of those three — fight back, flee, or avoid damage). At each stage, what happens depends on the actions of both combatants — what each of them is doing.

When somebody is trying to damage somebody else, let’s label the respective parties Attacker and Victim. In a fight scene, the Attacker makes an attack on the Victim — that is, Attacker takes some kind of aggressive action against Victim, such as throwing a punch, shooting a gun, firing a laser… The Victim also does something — dodges, projects a force-field, just stands there… What happens to Victim depends both on what Attacker has tried to do and what Victim tries to do (where doing nothing counts as a kind of doing something).

If Victim tries to dodge, then Attacker’s kick might miss. If Victim throws up her shield in time, Attacker’s laser might bounce off. If Victim does nothing to defend himself (perhaps he doesn’t know he is under attack, or perhaps he tries to retaliate without trying to avoid Attacker’s attack), then the attack might make contact. But even when an attack “lands”, what that actually means will depend, again, on the nature of Attacker’s attack and on what Victim is like. If Attacker has fired a bullet that hits Victim, it will have very different effects depending on whether or not Victim is wearing, say, a Kevlar vest.

a sequence

Fight scenes typically involve more than one thing happening — Batman punches the Joker, who then squirts back with acid from his trick flower, which Batman dodges while kicking out at the Joker, who topples… This is the prototypical kind of fight scene, in which two participants alternate between the roles of Attacker and Victim. First A attacks B, then B attacks A, then…

In principle, each action taken by Attacker and Victim could be depicted in their own panel, but usually an artist will collapse the panels (3) to one of four patterns:

1) Attack-Effect Dyad. Two panels, the first showing Attacker’s attack, and the second showing Victim’s action and the attack’s effect on him — e.g. panel one shows Attacker firing a gun at Victim, and panel two shows Victim successfully jumping out of the way so that the bullet whizzes past.

2) Attack Monad. One panel showing Attacker’s attack, with the resulting effect left off-panel, to be inferred by the reader as following this panel — e.g. we see Attacker firing a gun at Victim, who may or may not be shown (as yet unaffected by the attack) in the same panel.

3) Effect Monad. One panel showing the effect on Victim, with the initiating attack by the Attacker left off-panel, to be inferred by the reader as occurring before this panel — e.g. we see the Victim successfully dodging the bullet, which we infer to have been fired by Attacker immediately beforehand.

4) Attack-Effect Monad. One panel showing both Attacker’s and Victim’s actions, and the resulting effect on Victim — e.g. we see Attacker’s punch making contact with Victim within a single panel.

Naturally, an artist can use any combination of these patterns over the course of a fight scene, sometimes using one pattern and sometimes another. I’d guess — but I don’t have any figures to back this up — that the most common pattern, at least in American comics, is the Attack-Effect Monad, especially with fight scenes involving direct melee between combatants. Most fight scenes simply don’t parse action finely enough to differentiate between the moment when Attacker throws (say) her fist out in front of her at Victim and the moment when her fist actually makes contact with Victim. Instead, the easiest solution for most fight scenes is just to show everything all together.

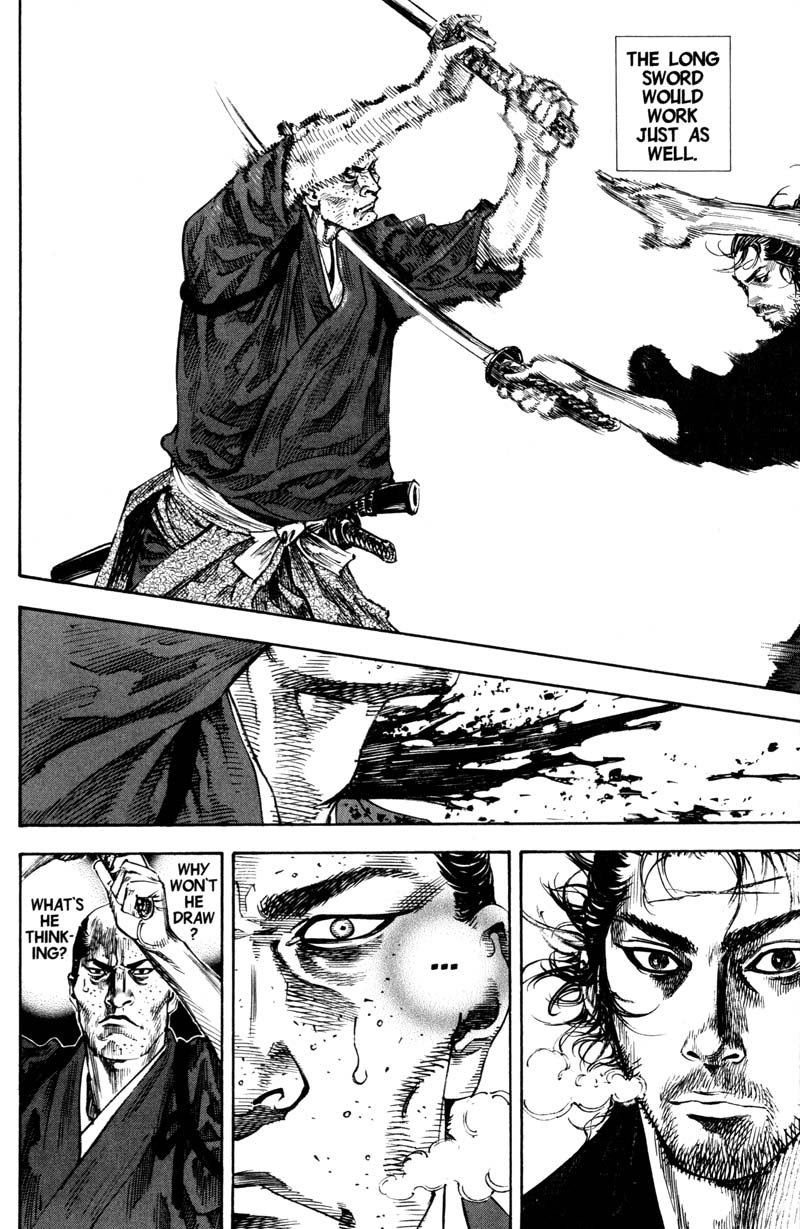

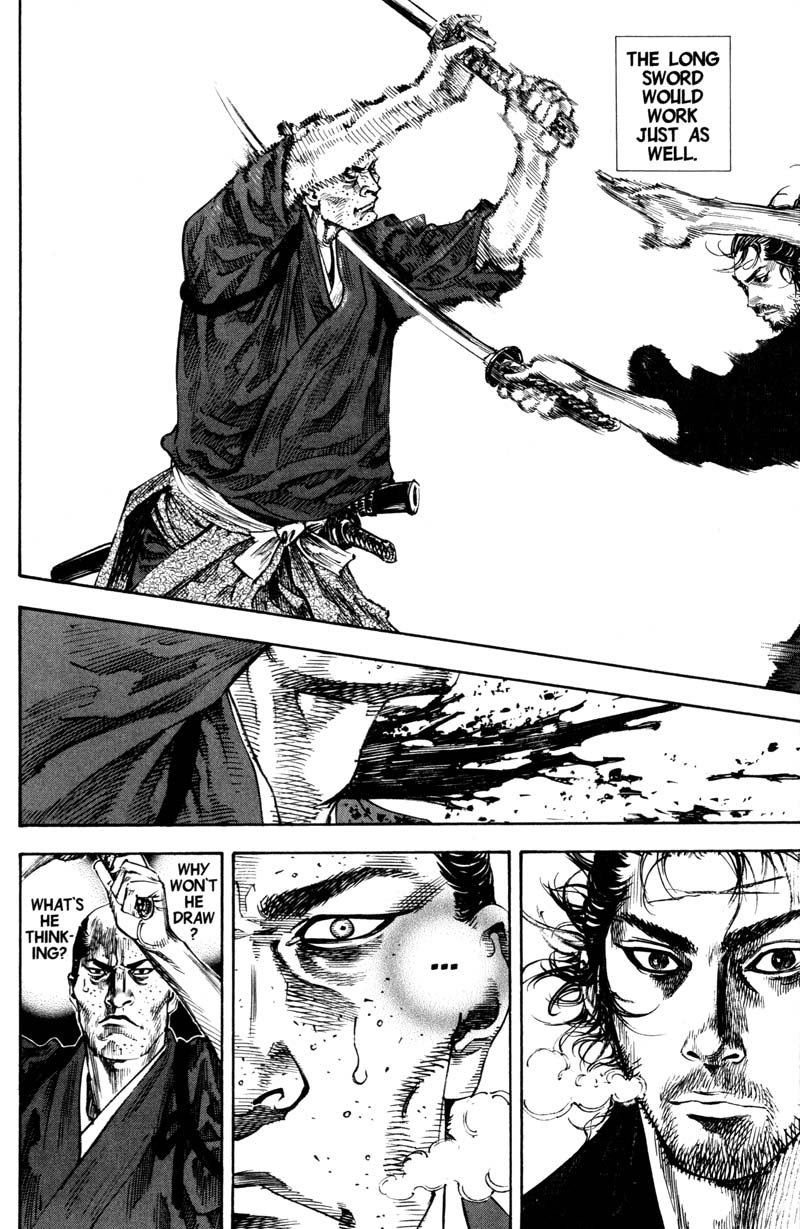

As with the number of participants, there is no upper limit to how long a fight scene can take. The Cerebus volume Reads has a remarkable fight sequence lasting for dozens of pages; Takehiko Inoue’s samurai manga Vagabond notoriously teases fight scenes out for hundreds of pages (although, to be fair, much of that does not involve actual fighting so much as flashbacks or other representations of the combatants’ streams of thought).

Kirby’s fight scenes can sprawl as long as an entire issue of twenty pages or more, although usually there will be some interruptions, such as a crosscut to a separate scene elsewhere. A fine example is the fight between Thor and the Absorbing Man in the main stories of Journey Into Mystery #121-#123. The entire sixteen pages of #121’s main story is given over to the fight, with a brief interruption in panels 3-6 on page 5 and panels 1-2 on page 6, in which we cut to Asgard and Loki (who has orchestrated the fight). The fight then continues in #122 from page 1 to the second-last panel of page 3, where we cut again to Loki who magically transports the Absorbing Man to Asgard. There the Absorbing Man fights basically the whole of Asgard, and eventually Thor again, until roughly page 10 of #123 (4).

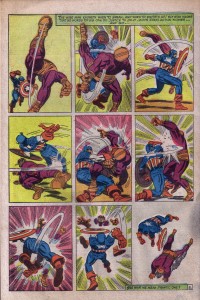

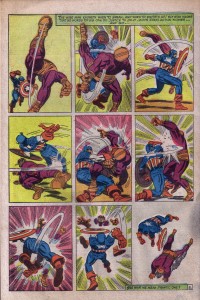

As an illustration of this formal structure, let’s do a quick close-read of another Kirby fight scene, and specifically a single, famous page from Tales of Suspense #85, inked by Frank Giacoia and lettered by Sam Rosen, with two captions by Stan Lee. (The comic doesn’t credit a colourist, and the listing at comics.org leaves it unknown). In this sequence we see a fight scene between Captain America and Batroc the Leaper (or, to give him the pantomime-French title favoured by Stan Lee and his later epigones, Batroc zee Leapair), which breaks down as follows:

Panel 1: First panel in an Attack-Effect Dyad. Batroc and Captain America are, each of them, both Attacker and Victim.

Panel 2: Second panel in the Attack-Effect Dyad, showing the effects of their respective attacks in panel 1. Again, each character is playing the role of both Attacker and Victim.

Panel 3: Attack-Effect Monad. Captain America is still Attacker but no longer Victim, while Batroc is now just Victim. We see Captain America’s attack and its effect on Batroc.

Panel 4: Attack-Effect Monad. Roles are reversed, with Batroc now Attacker and Captain America Victim.

Panel 5: Attack-Effect Monad. Roles reversed again, Captain America attacking and striking Batroc.

Panels 6-8: As with panel 5.

Panel 9: A breather — no attacks.

So I think this is a helpful way to think about the formal structure of a fight scene, in any genre: it’s a sequence of events caused by the aggressive and defensive (and other) actions of two or more combatants. But I really don’t know anything about proper comics theory, so please let me know in comments whether I’ve reinvented the wheel with my formal description of a fight scene above. If anything, I’ve probably reinvented the wheel, only this time it’s square and doesn’t turn very well…

In Part 2 of this essay, I’m going to talk about how this structure constrains the imaginative space of superhero comics, using Kirby’s The X-Men as an especially vivid case-study. So, come back next time, true believer, for more hot fucking action the Marvel Way. Excelsior!

ENDNOTES

(1) Although this scene doesn’t occur in any actual Superman comic, it does occur in roughly 98% of post-Watchmen superhero revisionist comics.

(2) Well, Captain America was actually created by Kirby and Joe Simon in 1941. But the 1960s revival was Kirby’s third-longest work in that decade, after Fantastic Four and Thor, so he certainly counts as one of Kirby’s chief characters of that decade.

(3) Just for the sake of convenience, I’m assuming that fight scenes are drawn in a standard panel lay-out, with one moment per panel. Things are a little more complicated when you have panels showing more than one moment in the same space, or ill-defined panels, but the basic idea is the same.

(4) I say “roughly” because it’s debatable whether the fight proper ends there, or three pages later when we see the final result of Odin’s magically expelling both Loki and the Absorbing Man into space. Debatable, but not really debate-worthy, you know?

IMAGE ATTRIBUTION: Stan Lee centerfold from Sean Howe’s tumblr for his book on Marvel. Captain America v. Batroc, credits as above; I took the image from Eddie Quixote’s Campbell’s post “The Literaries”. [Other images grabbed by Noah, who is less careful about documenting these things — so blame him, not Jones.]