People like long stories. More than that, they seem to like stories that last a long time.

People like long stories. More than that, they seem to like stories that last a long time.

They also like short stories, and stories that take a short time, but people like massively long stories so much that sometimes they make the short stories into longer stories, which keep going, and going, and sequelling and sequelling, and rebooting and rebooting, and fanfictioning and publishing fanfictioning, ad infinitum.

As the rebooting and fanfictioning testify, it’s not necessarily the plots that people want to continue endlessly—or perhaps plots just aren’t sustainable over decades (centuries, in some cases) being discrete units, usually. It’s the characters people want to live with, and the universes people want to live in. They don’t just want to find out what happens next. They want it to last.

Over time we have developed many, many ways in which to extend the life of universes and characters. Those stories that are created with the intent to be lengthy, however, usually come in three main forms: the episodic narrative, the serial narrative, and—well, for lack of a better term—the episodic serial.

First, let’s get some definitions out of the way. When talking about television, we use “episodic narrative” to refer to those programs in which entire plots are contained within an episode, and we use “serial narrative” to refer to those programs in which plots are comprised by multiple episodes, seasons, or the entire series. Episodic narratives include I Love Lucy and M*A*S*H; serial narratives include The Wire and Deadwood. The main differentiation is continuity; you don’t have to see previous episodes of I Love Lucy to understand the plot of an episode; to fully understand an episode of The Wire, you need to see at least several episodes—and, for complete understanding, the entire series.

<“Episodic serial” refers to an amalgamation of the two; episodic serials may contain an A plot that is wrapped up by the end of the episode, with elements referring to the B plot, which lasts as long as the season or series. Buffy the Vampire Slayer is a good example; some episodes contain the so-called “Monsters of the Week,” which are defeated by the episode’s end, but often bear some connection to the “Big Bad”—the villain Our Heroes spend the season fighting. This means that you can watch an episode of Buffy and understand most of what is going on, but you wouldn’t get the whole picture unless you watch a whole season.

Although these days these terms are generally used to refer to television, we have always had all three forms throughout the history of narrative—though rather than three distinct forms, there has usually been a spectrum between serial and episodic. Different societies and the media used to convey narrative have often favored one end of the spectrum or the other, often shifting fluidly from one end to the other and back again over time. These shifts, rather than marked by changes in preferences or changing ideas regarding the quality of either form, seem mostly marked by the two factors that shift everything: money and technology.

Oral tradition contained all three forms, but the most prevalent fall on the episodic end of the spectrum. This is most likely due to ease of memory. Episodic narratives keep a constant universe and characters (and sometimes tone), but do not require memory of plot. While serial narratives were (and are) common in oral tradition, it seems less likely that there were as many. You can still add to an oral serial narrative, which is the beauty of it—you can make it last as long as you want. However, you have to juggle lots of threads, if you want to write the next episode of The Iliad. The next myth in which Zeus Gets Laid Again, not so much. Without the technology of movable print, the narrative form that was easiest to recreate from memory was the one that was most common.

Movable type, invented in China in the eleventh century C.E., made works easier to reproduce, but it was still a pain. As a result, many of the texts written after movable type and before the printing press are still episodic. For both those using labor-intensive movable type, and those copying—rewriting, passing around, copying again, dictating, and rewriting again—works initially produced by hand, an episodic text would feel more manageable. You don’t need every segment to make the story “work,” you could just distribute the segments you preferred, depending on your agenda, or only copy down the ones you thought worthwhile. Again, it all comes down to ease. In this case, it’s not that episodic narratives are easy to memorize, but they’re easier to produce.

With Gutenburg’s invention of the printing press, it was possible to get a long narrative, in its entirety, into someone’s hands with relative ease. And thus marks a strange kind of bubble in the serial-episodic spectrum—because this is a strange kind of bubble in the history of Making Stories Last (A Long Time).

Works before the printing press, from The Iliad to The Canterbury Tales, were all stories produced and distributed over time. Many of them could be added to—either by readers or the original authors. The Tale of Genji, written over three hundred years before Canterbury Tales, and argued by some to be the first novel, was written by installments as the author distributed the stories at court; The Canterbury Tales were likely distributed a tale at a time.

While post-printing press romances or epics like Le Morte d’Arthur and two centuries later, Paradise Lost, are a lot more episodic than modern novels—or indeed, Enlightenment era novels—they were still published as single volumes. Within, they were split into “books,” but they could all be read at once (if that’s even possible). The intent was that they be sold at once.

So, while it can be argued that these works fall somewhere on the spectrum between serial and episodic, the works themselves mark a departure in the amount of time the consumer spends in the universe and with the characters. A consumer may spend just as long inside the work, if she desires to do so; it certainly can be argued that these works are just as lengthy as many narratives produced before. However, the consumer is not forced, as she once was, to wait (aka Make It Last).

The bubble burst with the invention of the steam press at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The steam press allowed for quicker, cheaper printing, and the invention marked the newspaper boom. Before this time, the printing press had certainly allowed for a democratization of knowledge, just like all our textbooks say. Still, a book was a relatively large expenditure—and not the most practical one, as compared to say, a loaf of bread. And in the past fifty years or so before the steam press, publishers were thinking up the genius scheme to “divide books for publication”—making one book three times as expensive, by splitting it into three volumes.

Newspapers, however, were cheap, and people who couldn’t afford books could often afford newspapers for a narrative fix. Thereby, newspapers allowed for a revival of a time honored tradition: making you wait for your stories. It began with episodic stories, probably due to the uncertainty in the early days of the newspaper boom—would this newspaper last? Would people pick it up, and try a new one the next day, or would it earn a loyal following? Could a serial narrative really work in this format?

Dickens’ first novel, The Pickwick Papers, isn’t actually really a novel. It’s a series of shorts about a group of characters, set in a particular universe. When it proved to be popular, publishers decided they could make money off of it by compiling the stories and selling them as a book. Probably a three volume set.

As Dickens and episodic narrative-constructing contemporaries gained in popularity, and some newspapers stabilized, the serial form took a firmer hold in the Victorian era. Most scholars mark a turning point between Dickens’ episodically structured novels and his serially structured ones; the serially structured ones still have distinct installments, but they also have tighter plots that depend on continuity to drive the plot forward. Many of the most famous Victorian novels were written in installments, for which the Victorian audience had to wait. Only later were these novels bound and sold in volume form.

By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the serial novel was going out of fashion. One reason may have been continued improvements to presses, which allowed novels to be cheaper and cheaper. Perhaps publishers realized they could sell more novels by producing works in one of volume and just demanding that they be shorter (Henry James didn’t listen). Perhaps people decided following a story in a newspaper was too difficult—and yet, while the evolution of modern novels spelled the end of serial novels, it didn’t spell the end of Making It Last.

Newspapers, after all, were still in production, and concurrently with the growth of the single volume novel we know and love today, came the rise of comic strips. Comics had always existed, of course, in various forms; some scholars would argue they existed before the written word. However, the nineteenth century newspaper boom caused the comic to take great leaps in terms of both commentary and story-telling, and by the turn of the century, we had the antecedents to what we know today as the Sunday funnies. Eventually—sort of like Dickens’ stories—strips were combined into books and sold as volumes.

As the serial novel started dying out and comic books started rising up, another medium that is engineered to Make It Last was on the rise—radio. Radio had both episodic and serial forms, and episodic serial forms, but when we traded it for television, narrative went mostly episodic.

The first television shows were televised plays, but once the technology evolved, and a lot of the middle class and up had them in their homes, people were getting Lassie, Leave It To Beaver, The Andy Griffith Show. Continuity on these shows would have been impractical, because unlike a newspaper, people couldn’t just pick it up and put it down. No one was going to stop their day every day at five to watch a program on television, producers thought, so most consumers couldn’t “follow along.”

Then, instead of television shows being produced live, they were recorded, and there could be reruns, and then reruns began to show in syndication. This made a little more continuity possible, because people could catch up with stories in reruns during hiatuses—or even enjoy the show the whole way through after its initial run on television, even if producers weren’t exactly writing to that possibility.

Next came the VCR, and suddenly people could tape things off television. We start getting shows like The X-Files and later, Buffy—no longer episodic. Serial episodic.

With the invention of the DVD, though, there’s another paradigm shift. Suddenly, it’s possible to do an eighty episode show on HBO that is just as reliant—some would argue more so—on continuity as some of Dickens’ later works. These suckers basically almost work like eighty hour movies, because you can go buy the whole set for fifty bucks—and isn’t that kind of just like Guttenburg; before, things are doled out in these small pieces, and then whammo—I can get all of The Wire and I can buy Paradise Lost right off the shelves.

Of course, there are a lot more threads to this, because there are a lot more media than books and television, and a lot of things going on in those media in particular. Why the serial narrative torch was mostly carried by comic books, and was completely dropped by serial novels, for a large part of the twentieth century is a mystery. While—since their emergence—comic books have always dwelt on a myriad of subject matter, it’s also a mystery as to why the superhero genre became so popular in the United States, when it was less so, for instance, in Japan. There are no doubt cultural reasons, as well as coincidences of timing and circumstance—and, as always—technology and money.

While comic books have always been popular in the United States, in Japan, manga emerged as a prevalent media outlet. From that emerged anime, which was making serial narrative a long time before HBO. As for American television, there have also been soap operas longer than there has been shows like The Wire, and soaps are for more reliant on serial structure. The reason for soaps probably has to do with audience. The target audience was a group that could be in the same time, same place every day, so they evolved on a different arc than much of the rest of narrative television.

Though shifts in preferences along the serial-episodic narrative spectrum seem motivated by money and technology, the undercurrent to all of it could be something deeper (or it could be the same thing, really). It’s all about Making It Last versus Getting It Now.

With Gutenburg’s invention, humans all seemed pretty happy with Getting It Now, and yet the first thing they did with the steam press was Make It Last. This was motivated by money, as I described—people who could not afford novels could afford newspapers. And yet, many people who could afford novels were reading serial installments in the papers—and then going to the extra extravagance of buying the book after it was all done.

These days, we watch the whole show as it airs and then go buy it on DVD. Maybe we do this because serial installments and daily programming are just the way it’s done. The first thing we did with television, after all, was Make It Last, but again, as I said, that seemed to be motivated by marketing decisions, and what technology made possible. After all, I, for one, don’t prefer watching television week to week. I would always just rather watch a whole show on DVD; I’m a Get It Now sort of person.

However, the Victorian style serial novel died out. Our novels became lean, and along with Hemingway, quite mean (in the sense of lacking excess; Hemingway is only sometimes unkind). Now that it is so easy to get a longer story on DVD, does that mean our television shows will become leaner—more like novels, or like movies?

The internet is our newest technology, and what are people doing with it, but writing Facebook and Twitter novels? Oh, sure, people are doing all sort of things with it—they’re serially blogging, and breaking things up into installments so that they’re easier to read day to day, and Twitter novels don’t seem to have much at all to do with money or how to rope in a consumer to buy a higher volume of products. They seem to be about wanting to spread things out, Make It Last.

After all, despite the economic reasons behind Making It Last for the consumer, there are plenty of narrative points in its favor. Victorian novels are famous for their length and wandering pace, but their method of distribution made it possible to lay out a hundred different threads. With each installment, these threads could slowly be picked one at a time, or put down, tied together with another thread, or unraveled a bit at a time (or dropped completely, as sometimes happens).

There seems to be no room for that, in many modern novels. There is very little room for people sitting around talking; there is very little room for mutants sitting in the mansion talking about how life sucks. There is very little room for Xander to go on his own adventure while Buffy, Willow, and Giles try to save the world, thanks. There may be room, in a blogged novel, to do these things. (I’m still not sure about Twitter, though. There doesn’t seem to be room for anything. Even this parenthetical is probably too long.)

Of course, there’s no way to draw any absolute, causal conclusions about the kind of narrative people want. They want all kinds; when they Get It Now, they want to Make It Last. When they get episodic, they want serial. All of these different elements are in such a mish-mash of what is possible with current media, that in the end, it always seems to me that writers and creators are always going to find a way to do something different with it.

And publishers and producers are always going to find a way to make money off it.

Mariah Carey, Memoirs of an Imperfect Angel

Mariah Carey, Memoirs of an Imperfect Angel AmerieIn Love & War

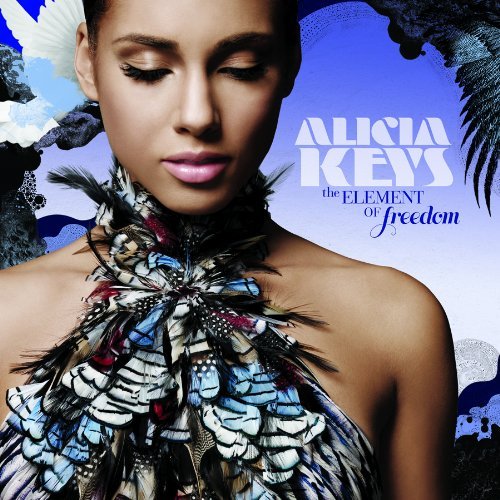

AmerieIn Love & War Alice Keys,Element of Freedom

Alice Keys,Element of Freedom