A slightly edited version of this ran on Splice Today.

____________________

Towards the end of Steven Pinker’s new book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, he asks “whether our recent ancestors can really be considered morally retarded.” “The answer”, he concludes, “is yes.”

Pinker condemns his (and our) forbearers for two reasons First, he shows that the rates of violent death throughout the world have been declining for almost as long as there are records. Hunter-gatherer tribes with no state system has higher rates of homicide than ancient empires; ancient empires had higher rates of violent death than did 18th and 19th century Western societies, and so forth. Second, Pinker argues that the decline in violence has been the result of enlightenment — in its technical sense. The ascension of Western Enlightenment values like democracy, free trade and human rights have civilized the formerly barbaric, religion-haunted, blood-soaked planet. Locke and Voltaire and Darwin said “beat your swords into abacuses,” and that is precisely what the world has done.

Pinker’s thesis is both optimistic and polemical. It suggests that the human species has made massive progress, and that that progress is attributable to Western Enlightenment ideology. Among the aspects of that ideology that Pinker praises are:large states (the Leviathan) which monopolize violence and thereby reduce interpersonal murde; democracy, which statistically appears to make states less prone to violence; free speech and broad education, since literacy and the distribution of books increases the ability to see other’s perspectives (and since the availability of books seems to correlate with the widespread decrease in violence); and the expansion of women’s rights, since women are overall less violent than men, and their influence tends to stabilize and civilize. Most importantly, Pinker praises scientific thinking itself, which Pinker credits with giving individuals a non-parochial perspective, allowing them to break free of the blinkered Prisoner’s Dilemma and see that peace is best for all.

The spectacle of a Western author and scientist triumphantly proclaiming the virtues of the West, books, and science is not especially surprising — though I was a bit taken aback when Pinker, a prosletyzing evolutionary psychologist, proudly proclaimed that one of the causes of the decrease in violence might be the spread of the ideas of evolutionary psychology.

But however clear Pinker’s biases may be, and however skeptical one may be of the thesis that we are the best people in all of history (and I am quite skeptical), Better Angels is an imposing, not to mention mammoth, brief. With 700 pages and graph after graph moving inevitably down and to the right over time, he shows, at the least, that by many measures violence per capita in our society is at world-historical lows. The claims that ours is an age of terrorism, or that Americans are less safe than they have ever been, is, patently, bunk.

Some of Pinker’s other assertions are more questionable. Here are a few.

—Pinker’s absolutely right that gay rights have improved enormously since 1950. But that ignores the fact that many the 1950s in the West was a particularly horrible time and place to be gay. Gay people were certainly worse off in the mid-20th century West than they were in Ancient Athens, or even in early 19th century England.

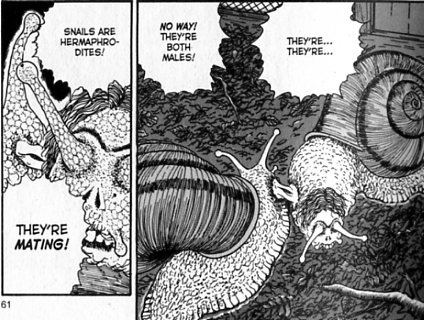

—His insistence that animal rights have been constantly improving since the Middle Ages seems somewhat contradicted by the rise of vivisection and animal testing. Even if, as he contends, people treated animals horribly in the 14th century, and even if, as he claims, vivisection has declined over the 20th century, science still tortures animals at rates that would impress (if not particularly horrify) our morally retarded ancestors. And this is without even discussing humanity’s role in our current ongoing planetwide species mass extinction event.

—Weapons have improved over time. This suggests that weapons, and war, have become more violent over time. Pinker responds to this by explaining that swords and arrows were plenty deadly — which rather begs the question. Nobody denies that arrows are deadly. But machine guns are a lot more deadly than that, and nuclear weapons are more deadly again. If you read John Keegan’s The Face of Battle, which discusses Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme, you are impressed first by how utterly, hideously horrible Agincourt was — and then by how much exponentially worse Waterloo was — and finally by how monumentally, unbelievably terrible the Somme was. Pinker spends a lot of time discussing the deadly effects of low tech weapons and medieval torture devices, but he spends little to no time talking about the much, much more deadly effects of our current arsenal. His silence on these matters speaks for itself.

One of the biggest question marks in Pinker’s book, though, is his handling of the first part of the twentieth century — the lovely years from World War I in 1914 through Mao’s famine in 1964, with the Holocaust, Stalin’s purges, and several neighboring atrocities thrown in. If you’re trying to prove that the world has been becoming more peaceable, that’s an awful lot of relatively fresh bodies to sweep under the carpet.

But Pinker goes for it. He first attempts to make World War I and World War II vanish into statistical noise mostly by adjusting them for world population. At 55 million, World War II is overall the largest catastrophe in the history of the world. However, if you adjust for world population, it is only the 9th largest. The biggest would instead be the An Lushan revolt in 8th century China, which Pinker says killed 36 million people over 8 years; a number which would work out to 429 million dead proportionally in the 20th century. Other conflagrations which beat WW II proportionally are the Mongol Conquests (40 million raw, adjusted to 278 million by population) the fall of the Ming Dynasty (25 million raw, adjusted to 112 by population) and the annihilation of the American Indian (20 million raw, adjusted to 92 million by population.)

It’s certainly worth remembering that people have done hideous things to each other for a long time. Even if no one is really sure that the An Lushan rebellion killed quite 36 million people, there’s no doubt that a staggering number of people died. Even if the Fall of Rome lasted over three centuries as opposed to the 6 years of World War II, 8 million dead is still a ton of dead people, as are the 40 million killed over the century of the Mongol Conquests. The recent past was by no means the first era of murder on a massive scale.

Still, one might argue that geeking out on statistical weighted tallies of dead is more than a little obscene. And one would be right. Human beings aren’t just numbers. Every dead person matters. Pinker insists again and again that the romantic ideology of the Nazis had nothing to do with enlightenment modernity and its march towards clear eyed utility, but he is least convincing on this point when he starts to fiddle with his death tolls in order to make his graphs look pretty. Counting World War I, World War II, Mao’s famine, Stalin’s purges, the Russian Civil War, and the Chinese Civil War, 142 million people died through atrocity in the first part of the twentieth century. That’s twice as many people as lived in the entire Roman Empire, and probably 10 times as many as lived in the entire world before the agricultural revolution. Does that make the number less obscene? More? What exactly does even asking the question accomplish? People look back on the early twentieth century as one of unique horror not because they’re naïve, or foolish, or because they’re not as scientifically astute as Steven Pinker. They look back on it as a period of unique horror because it was a period of unique horror.

For all his tables and weighted numbers, Pinker is honest enough to admit as much. He argues, however, that the unique horribleness is not a function of modernity, but an aberrant blip caused by the insanity of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. “Tens of millions of deaths ultimately depended on the decisions of just three individuals,” he insists. He adds that without the assassin who shot Archduke Ferdinand, there would have been no World War I. The early twentieth century, therefore, tells us nothing about violence in general, except that bad luck sucks.

The problem with this is that bad luck is universal. Insane assholes have existed forever. Genghis Khan (who Pinker discusses) for example, was a blight on the face of the earh Christopher Columbus’ genocide of the Arawak peoples ranks him as one of the monsters of history.

Both Genghis and Columbis killed and tortured lots of people. But they didn’t kill and torture anything like the number of people Hitler or Mao or Stalin did, for the simple reason that state apparatus and technology had not developed sufficiently to allow them to do so. As Tyler Cowen argues , the increase of state power, damps down individual violence, but it can vastly increase state violence as well. Thus, slavery has always been a bad thing, but it took centralized European states to create the rationalized, large-scale African slave trade that even Pinker calls “among the most brutal chapters in human history.” Cowen suggests, therefore, that “one way of describing the observed trend [in violence over time] is ‘less frequent violent outbursts, but more deadlier outbursts when they come.’”

Which brings us to nuclear weapons. Pinker argues forcefully that nuclear weapons need never be used, and that our ever-growing conflict-aversion may help keep them in their silos forever. One data point he uses here is the Cuban Missile Crisis. According to Pinker

Though the pursuit of national prestige may have precipitated the crisis, once Khruschev and Kennedy were in it, they reflected on their mutual need to save face and set that up as a problem for the two of them to solve.

That’s certainly a comforting way to think about it. However, in most accounts I’ve read, the resolution was achieved less through mutual face-saving, and more through Khruschev unilaterally deciding that he didn’t want to destroy the earth. This wasn’t, in other words, an example of an ultra-civilized meeting of minds; it was, instead, the usual pissing match, which one monkey ended by baring his throat.

This interpretation seems to better fit the facts, inasmuch as Khruschev’s face wasn’t saved; he had to back down and remove his missiles from Cuba. Kennedy’s quid pro quo — removing missiles from Turkey — was done in secret so that the President wouldn’t be punished at the polls for “weakness”. Gary Wills in Bomb Power concluded that Kennedy “risked nuclear war” rather than lose public standing. I’m able to type this today not because two world leaders behaved in a civilized and dignified fashion, but because Khruschev was not as much of an insane asshole as Kennedy. And he was not as much of an insane asshole, arguably, because he didn’t have to worry about an electorate. So much for the peaceful influence of democracy

The thing that is most troublesome about Pinker’s book, though, isn’t so much the occasional fissure in the argument as the tone. The suggestion that your grandparents and mine were moral fools is not exactly typical, but it’s not isolated either — and it’s not confined to the past. John Gray points out that Pinker tends to label certain peripheral groups (Muslims, for example, or hippies, who he blames for the rise in murder rates in the 1960s) as less civilized. Therefore, violence is associated with these groups because they are backwards or not sufficiently rational, rather than a function of power disparities or politics. As Gray says:

A sceptical reader might wonder whether the outbreak of peace in developed countries and endemic conflict in less fortunate lands might not be somehow connected. Was the immense violence that ravaged southeast Asia after 1945 a result of immemorial backwardness in the region?

Pinker’s disavowal of the effects of politics is consistent with his vision of rational enlightenment, which he sees as specifically outside of power relationships or communities. Science and reason, he argues, allow for “an Olympian, superrational vantage point — the perspective of eternity, the view from nowhere.” For someone who claims to find so little of worth in God-talk, that’s some oddly theological language there interlaced with the self-vaunting. Or does it not count as theological if your divine ideal is human? And on what grounds, then, do you so entirely disavow the enlightenment’s relationship to Marx?

None of this upends Pinker’s thesis, of course. But it does suggest that some caution might be in order. We should acknowledge, and celebrate, the reduction of violence in the world where and when it occurs. And we should acknowledge the part modernity has played in that, and in many other advances. But Pinker himself notes that elevated self-esteem — perhaps we could say hubris? — is one of the many factors that can lead people to violence. There are others of course, such as a faith that one has discovered the ultimate true path that will lead the world to peace. Or, for that matter, a faith in the transformative power of evolutionary progress, sometimes known as eugenics, from which some bad things have flowed in this, our modernity.

Pinker likes to see himself as a contrarion, but reason, science, progress, and self-regard are hardly anathema in our world’s wonkish corridors of power. Since one of the gifts of the enlightenment is a questioning of orthodoxies, it seems only reasonable to question the orthodoxy of enlightenment as well. Among other things, we might consider the possibility that there is something morally retarded in believing that we are the most morally advanced individuals to ever walk the earth. Perhaps we could also think of peace less as an algorithm and more as a gift, for which we make ourselves continually worthy through humility and contrition. Acknowledging our successes is certainly part of that, but so is admitting to our failures. Modernity is both our long peace and the guillotine. I don’t think that downplaying the second will extend the first.

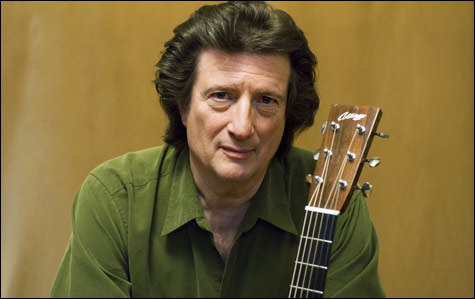

The thing about Chris Smither, though, is that, while he is a 100% bona fide, folk revival fossil down to his witty self-deprecating patter (“I love this place. I feel like I’m such an artist”) and the easy liberal jeremiads (“the trickle down will float you up…surprise, surprise, it ain’t so”) he’s also, actually — well, good. His blues-derived guitar playing is a wonder, whether swinging through a dirty Lightning Hopkins rave-up like “Surprise, Surprise” or using a lighter, Mississippi John Hurt-style flow as on “Time Stood Still.” His voice is hoarse, and his mumbled phrasing is remarkably evocative, like Tom Waits with half the booze and twice the brains. Everything, down to the incidental aspects of his set — the way he uses both feet to create barely audible (though mic’ed) percussive rhythms, or the effortless speed with which he downtunes between songs —is done so professionally, and with such unpretentious nonchalance, that it attains soulfulness almost by default. His performance of “Sittin’ on Top of the World,” which closed the night, was near definitive — a slow, almost-dirge where every drawn-out, supposedly carefree line dripped with bittersweet longing. Even my wife liked him. In fact, she bristled a bit when I informed her that he was, indisputably, and despite his many good qualities, clearly of the folk revival. (“I guess I did hear about him on NPR,” she finally admitted reluctantly.)

The thing about Chris Smither, though, is that, while he is a 100% bona fide, folk revival fossil down to his witty self-deprecating patter (“I love this place. I feel like I’m such an artist”) and the easy liberal jeremiads (“the trickle down will float you up…surprise, surprise, it ain’t so”) he’s also, actually — well, good. His blues-derived guitar playing is a wonder, whether swinging through a dirty Lightning Hopkins rave-up like “Surprise, Surprise” or using a lighter, Mississippi John Hurt-style flow as on “Time Stood Still.” His voice is hoarse, and his mumbled phrasing is remarkably evocative, like Tom Waits with half the booze and twice the brains. Everything, down to the incidental aspects of his set — the way he uses both feet to create barely audible (though mic’ed) percussive rhythms, or the effortless speed with which he downtunes between songs —is done so professionally, and with such unpretentious nonchalance, that it attains soulfulness almost by default. His performance of “Sittin’ on Top of the World,” which closed the night, was near definitive — a slow, almost-dirge where every drawn-out, supposedly carefree line dripped with bittersweet longing. Even my wife liked him. In fact, she bristled a bit when I informed her that he was, indisputably, and despite his many good qualities, clearly of the folk revival. (“I guess I did hear about him on NPR,” she finally admitted reluctantly.)