Whoever would not understand me would not understand any better the roaring of a tiger. Aimé Césaire

I never knew Jean-Michel Basquiat, although we were of the same time and place and had friends in common, but I recognized his abilities the moment I saw his work. I can still recall how his painting resonated from the wall in a closely hung group show at CHARAS in the early eighties. It rivaled the intensity of the Alice Neel portrait across from it. Although his paintings have singular appeal in terms of their brilliant coloring alone and their marks always feel fresh, there is much more going on than just a painterly surface. They articulate a position in regards to art and history, often elucidated in a textual form where what is obscured or erased is given the same weight as what is visibly spelled out.

Basquiat’s work emerged in the early 1980s as his contemporaries in Graffiti achieved their too-brief moment of American Art world acceptance, but even when he was spraypainting on the street he did not share that movement’s form and goals. The graffiti entity SAMO created by Basquiat and his friends Al Diaz and Shannon Dawson wrote poetic sentences on the streets of Soho, with a obliquely critical tone directed at the wealthy people who lived and shopped there. Basquiat’s work was never about the evolution of illuminated lettering forms that characterizes aerosol art. The late theorist of weaponized letters Rammellzee commented that his friend’s writing was “unreadable…(he) crosses out words, doesn’t spell them right, doesn’t even write the damn thing right.” Nor does Basquiat have common ground with the decorative confections of his friends Keith Haring and Kenny Sharf, despite that he is most often placed in their context by Art pundits.

Instead, his paintings relate better to the guerilla subversions practiced by another of his East Village peers, David Wojnarowicz. Basquiat and Wojnarowicz were both subject to inversion of identification. As Wojnarowicz’s multimedia works expose and excoriate a culture that refuses to accept or acknowledge his homosexuality, Basquiat’s paintings layer and refashion the racist cultural signifiers imposed on him that did not reflect his image. Like Wojnarowicz, he used his art to highlight the disparities, omissions, and lies in the histories of Art and Civilization. According to bell hooks, to reach his goals Basquiat “assumed the role of explorer/ colonizer,” he “journeyed into the heart of whiteness. White territory he named as a savage and brutal place.” Our mutual friend the painter Stephen Lack says, “Jean-Michel gave his paintings great import.” Once ensconced in the pantheon, Basquiat pursued the purposes of information dissemination. His messages were radical but effectively composed within specific referents to pass through the filtering apparatus of white art appreciation as guided aesthetic missiles.

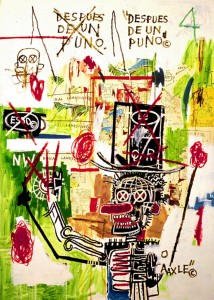

The textual aspects of Basquiat’s works incorporate a sophisticated multilingual approach. His use of Spanish relates in poetical terms to the linguistic claims of the Nuyorican movement, in that he deliberately use languages and the purposeful obscuring of written text to address, or privatize his words from, specific aspects of his audience. This paradoxical offering and withholding of understanding is seen in the painting “Despues De Un Puno,” where the text prominent in the piece is intended to block comprehension, as in comments he was known to make in Spanish to acquaintances in the presence of presumably ignorant patrons. Conversely, Basquiat does not close off the option of expansion of language. Typically his text operates in the opposite direction too, in order to self-proclaim his multilingual fluency and expand the linguistic possibility of his reach. On the interchange of language, the fluid switching between Spanish and English within a sentence seen in bilingual Puerto Ricans, Juan Flores writes, “rather than compensating for monolingual deficiency, code switching often signals an expansion of communicative and expressive potential.” As such a code switcher, Basquiat is able to draw from a wider reservoir of signifiers with the languages at his command.

Basquiat knows the history of the conqueror and the actualities of his current position within it, how it relates to his body. His quoting of corporate symbology and recurring impositions of trademark and copyright symbols speak to issues of ownership: of the land, of his ancestors, of himself, his body and the products of his brain and hand. His methodology is a form of layering of textual and visual signifiers that resembles the approach of other artists of his generation such as Wojnarowicz and Christof Kohlhofer, whose images consist of a profuse visual and textual “namedropping” invested with a multitude of sub-signifiers of shared experience. Basquiat communicated directly with the art world using their referents, their signifiers. In his paintings Basquiat links the significance of words or phrases set in proximity to each other in their context within the pictorial field. This allows associations to be followed by the viewer/ reader in a type of narrative of assimilated ideas. Basquiat contexualizes the Diasporan experience with the Western canon as Aimé Césaire did with Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” while he also bridges the gap between visual and textual signification.

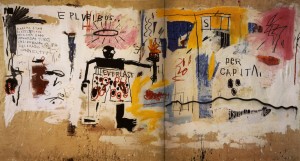

In the relatively spare piece “Per Capita” large lettering in Latin dominates the background field or storefront space. Basquiat uses Latin like other poets to point to his scholarship and to place himself amongst the great classical poets, but perhaps also like Elisabeth Barrett Browning, who as a marginalized female poet uses a Latin header on a poem to demonstrate her equality to the male Victorian poets, Basquiat claims equality across racial lines. He affirms that he knows the canon and claims a stand on even ground. Further, the work is surmounted on the left by the inscription “e pluribus,” or “out of many” (sans unum or “one”) as on coins and currency and on the right by “per capita” or “per head.” In this way he points to the way white classicism hides the ugly truth of people counted like numbers, in a nation built with slavery.

Down the left side are listed the names of states and figures in dollars. The highest amounts are tallied by predominantly white states, Connecticut and Alaska and the lowest to states with large African American populations such as Alabama. This listing taken with the title might indicate a sliding scale of income or funding allocation for each individual in the respective states. It might also reflect a type of ordering that allays the anxiety of those who are displaced. On a pictorial level, the painting depicts a boxer with a halo holding the torch of liberty. The shrunken, attenuated black figure with blank eyes wears oversized shorts with the logo “Everlast” emblazoned on it conspicuously. It is typical of the ambiguity and self-ironizing of Basquiat’s work. “Everlast” places the black male as enduring forever as the champ, who can withstand a pounding as well as deal one out, yet in the end still answer to the sponsors and handlers who see him only as a commodity. Basquiat points to the endurance of people of color as they are used by the dominant culture. The text qualifies the terrible skepticism of the piece with extreme brevity.

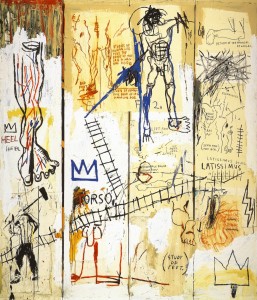

In “Leonardo Da Vinci’s Greatest Hits,” on four vertical strips of canvas Basquiat arranges distorted renditions from “Gray’s Anatomy” and Leonardo’s notebooks with an emphasis on legs and feet. The title suggests that Da Vinci also was pressed by his patrons to produce on demand and even repeat his most popular works, his “hits.” Basquiat refers to “the bad foot, the left foot” and with “Return of the Prodigal” he identifies as the bad son. “Heel” is repeated, which might define as being under a heel, or down at the heel, a heel in the sense of bad, a villain, or a flaw or weakness as in an Achilles’ heel. In the bottom left is a muscular figure with a mallet like John Henry, building the railroad tracks that the whole is crossed with, “hits” to make tracks perhaps as references to drugs, tracks that mark a slave to a habit, marks which take on the form of text themselves, used semantically to represent history. They unify the piece and lead on one path to Latin again with “Latissimus”, muscles of a strong back, on the other track to “studies of human leg plus the bone of the leg in man and dog.” A dog can be trained to “heel.” Perhaps the influence of Césaire’s line, “that it is enough for us to heel the world, whereas the work of man has only begun” is here as Basquiat feels the inherited burden. Yet perhaps it also recalls the anxiety caused by the sense of alienation from the body as a legacy of slavery.

The sense of the physical body is also in the piece as he refers to Shelley’s poem, “Prometheus Unbound” about the bringer of fire Prometheus’ emancipation from torment as “Prometheus Bound,” prefiguring release and again locating himself within the framework of revolutionary poets, but here insisting himself as both Prometheus the bringer of fire, a metaphor for the fire of his message and a reference to freeing himself from the long suppression, now pushed back into even earlier times. The poem cements the images of fighting back and rebellion together with flight and escape. The flight might be seen like Prometheus to claim his due or perhaps as away from the brutalization of exploitation. Basquiat trades in ambiguity and this is a hallmark of his work.

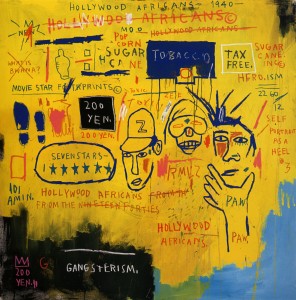

Correspondences can be found throughout the text of Basquiat’s work, as in “Hollywood Africans,” a caustic piece painted mostly yellow with the footprints and portraits of his writer friends, Toxic and Rammellzee, with his own likeness simultaneously valorized as “hero.ism,” villianized as “heel #3” and animalized with “paw.” There were few Africans in Hollywood that were not racist representations of savages and servants. The reader is asked, “what is bwana” in the form of a question as in the TV game show “Jeopardy” and crossed out. Basquiat is ventriloquizing white concerns, it’s not real. The lines of races and assimilation are crossed and blurred. Seven stars is too many, it’s pop, it’s corn, Idi Amin may be a black dictator in the real Africa but the sugar cane in Haiti is incorporated and copyrighted to be exploited, it all adds up to the sum of white on black “gangsterism,” it’s real and the piece is priced at 200 yen.

Belying the portrayal of him in Julian Schnabel’s film biography as a mumbling, bumbling junkie, the volume of work Basquiat produced in his short life is that of a dedicated painter, with little time for anything but work. Stephen Lack suggests that when Basquiat’s dealers requested that he switch from painting in acrylics to make more valuable products in the medium of oil, the prolonged drying time of oil paints adversely affected the artist. Lack posits that Basquiat then had to wait for a layer of pigment to dry before adding successive layers, depriving the work of spontaneity and the artist of his most valued rush, the more immediate pleasures and gratifications of creating large-scale works quickly in fast-drying acrylic. And, the paradoxes of his position and the fickle and judgmental nature of celebrity in the art world overwhelmed him. Frances Negron-Muntaner observes,

While Basquiat envisioned commodification as a way out of the racialized body to the extent that it socially valorized him, the requirements of steady output undermined his independence and relationship to painting, making the artist fatally aware of his shameful status as a racialized subject, even under privileged conditions.

Basquiat had truly believed that he would be able to scale the heights on his abilities and worth, but the tipping point was reached when the critical reaction to his collaborations with Andy Warhol hurt him. He was othered, treated as a novelty brought to life by Warhol’s divine intervention. He could not accept the sidekick role, could not be subordinate—it was he who had invigorated Warhol with his love and energy. It was now clear that in order to continue he would have to subsume himself and his art further into a system which did not regard him as an equal.

In less than a decade, Jean-Michel Basquiat sealed his fame with a large body of work and sacrificed himself in the process. He felt the oppressions of millenia, he internalized the damage done no less than did the tragic Puerto Rican poet laureate Julia Burgos. Like Burgos, in the end he died alone, and although they didn’t cut his limbs off to fit him into a pauper’s coffin as was done to her corpse, he was also dismembered. Parts of him are in many public and private collections. His art stands as a painterly, eloquent, accusatory text, a litany of sure marks which express the weight of centuries of dislocation, testimony and evidence presented against the culture that ate him.

It’s as if I’d like to return,

and yet can’t discover why, now where to.

Julia Burgos

____________________________________________________________________

Thanks to Marguerite Van Cook, Frances Negron-Muntaner, Stephen Lack and Sur Rodney Sur.

In an pre-publication

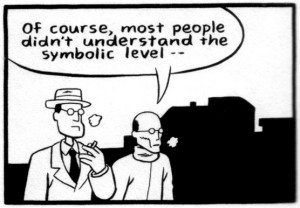

In an pre-publication  Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form.

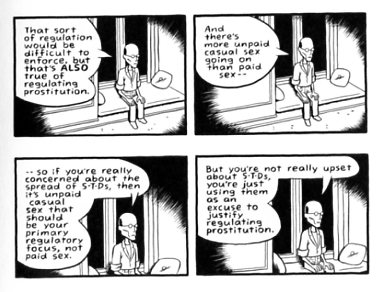

Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form. Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).

Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).  Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement.

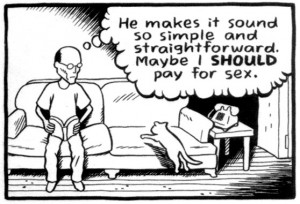

Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement. And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.

And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.  One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book,

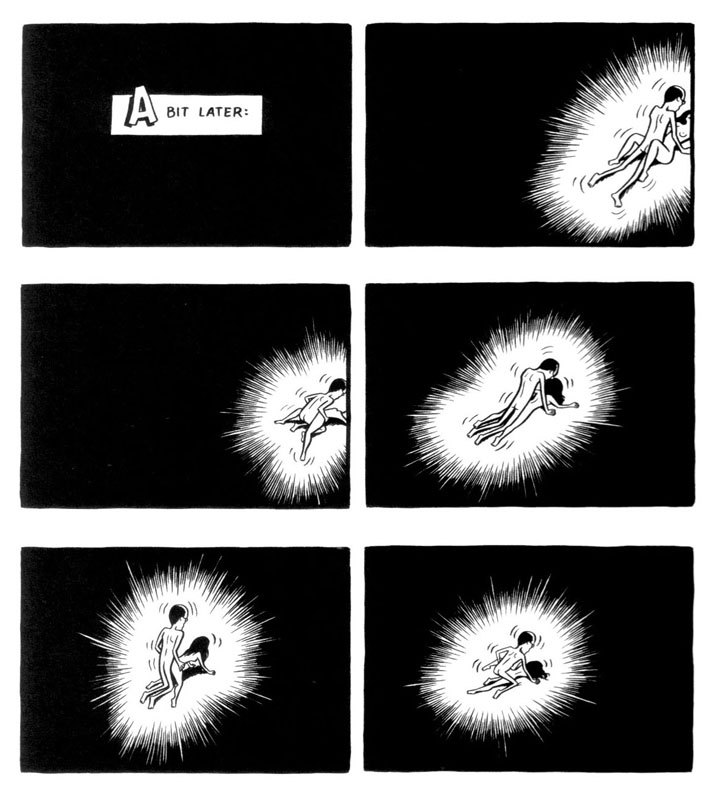

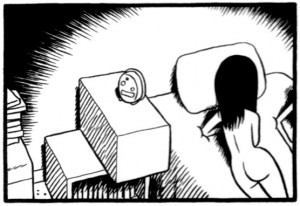

One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book,  As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.