Women in the IDF are, horrifying though this may seem to a young teenage boy torn between hormones and politics, quite attractive. That this merits a good half a page in Joe Sacco’s “Palestine” tells you that this is a man who knows his Holy Land. In fact Sacco knows it well enough to recognise the truth which overwhelms even the casual visitor to Palestine; everyone has a story. I can remember a lecture I once attended on the history of the Israel/Palestine conflict where, after much deliberation, the relevant academic was forced to give two lectures on the same events, one in the persona of an Israeli settler, the other as a Palestinian militant. The point being, no single viewpoint or narrative could fully encompass the vast and polarised history of this country. This is obviously true of all countries, and all histories, but it is perhaps even more pertinent in Palestine, where history plays a disproportionately large role in shaping the attitudes of the now.

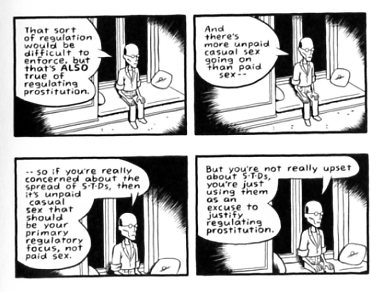

This is an idea that Sacco attempts to confront head on throughout his work in the region. He acknowledges how insufficient the single narrative is, and, as a journalist, how limited the dominant story that fills most of the media is. In “Footnotes in Gaza”, Sacco sets out to tell an alternative, to tell the story of the ‘footnotes to history’: the victims rather than the oppressors. In an exercise of oral history, the Palestinians are to be allowed to express their own voices, to speak in their own words about an event, the massacre of 111 Palestinians in the Gaza town of Rafah in 1956.

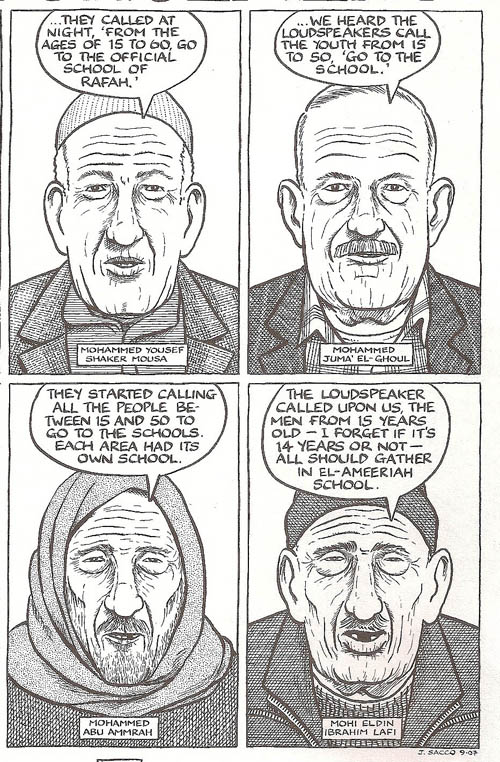

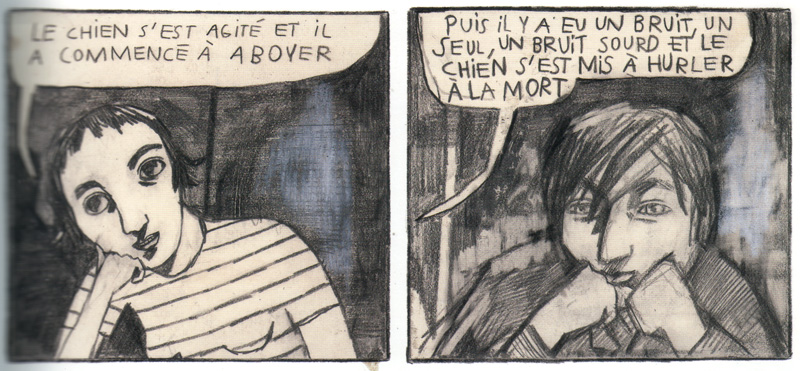

If “Palestine” is ‘graphic-journalism’, then “Footnotes” is arguably graphic-history, Sacco employs his enviable skills to bring to life not only the accounts themselves, but the process of collation. He scales down the expressionistic, Crumb-esque caricatures of ‘Palestine’ and exchanges them for a more realistic aesthetic, with some impressive detail and an especially sharp eye for landscape composition. The eye-witnesses whose testimony are portrayed are drawn as head and shoulders mugshots, speaking directly out of the page, in an evocative portrayal of the victims indeed speaking in their own words. There’s a lot of this direct portraiture, again and again eyes are directed out of the page at us, there’s rarely the experience of detached viewing.

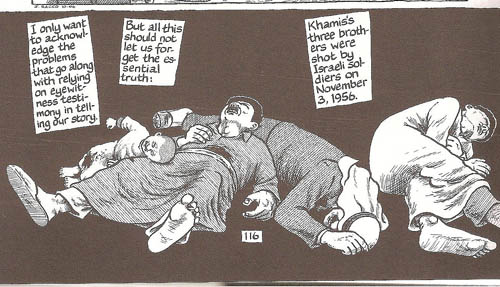

Despite his commitment to allowing the victims to simply tell their story however, Sacco acknowledges, and engages with, the necessity of drawing narrative from memory. With as much of the text concerned with the modern day collection of the oral accounts as with the history itself, Sacco is able to express concerns and difficulties with the oral testimony. He complains about the weakness of memory, the conflating of events and the exaggeration and elaboration he finds as he compares accounts. In the memorable segment entitled “Memory and the Essential Truth”, Sacco takes several different testimonies of a single event, the killing of three brothers, and compares their omissions and deviations, before finally concluding that the only confirmable truth, and yet also the only one which matters, is that three brothers were killed. The sequence becomes a justification of the methodology of the entire history, from this point on events are narrated by a succession of witnesses, with Sacco demonstrating both the convergences, and the deviations between the accounts.

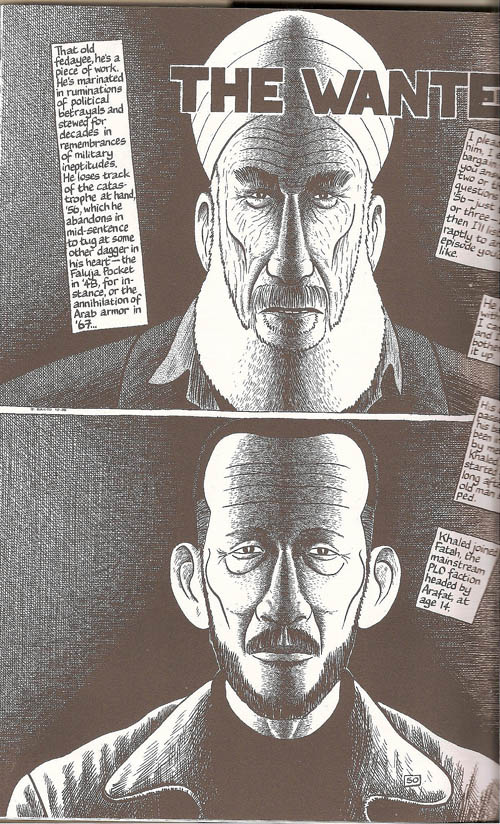

Another instance where Sacco steps outside of his simple historical narrative is in his comparison, and then conflation, of past and present. He notes the tendency of his subjects to prioritise the current over the past, to focus on the latest atrocity with no importance assigned to the past. He is slightly perturbed to realise there is little understanding of why he cares about 1956. So he shows us the importance, shows us the connections and repetitions of history, drawing visual parallels between militants past and present, as well as places and rhetoric. As Nina Mickwitz explains in a much more detailed reading of the panels than I’m capable of, the very composition of the page often seems to reinforce the cyclical nature of the conflict, where the past is repeatedly played out in the present.

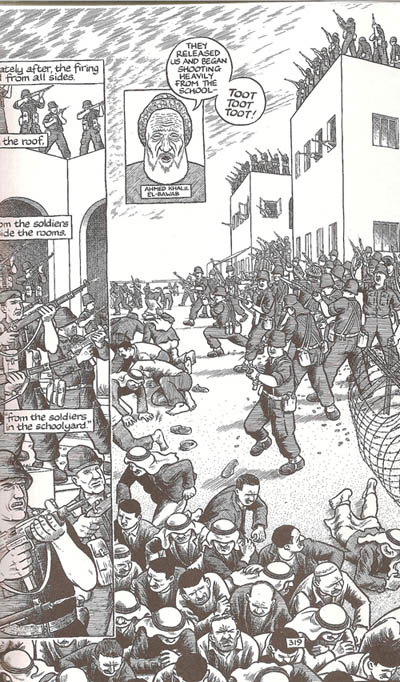

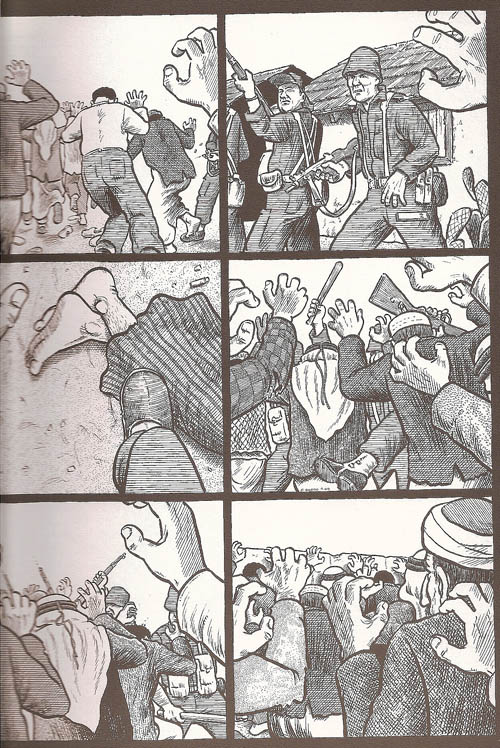

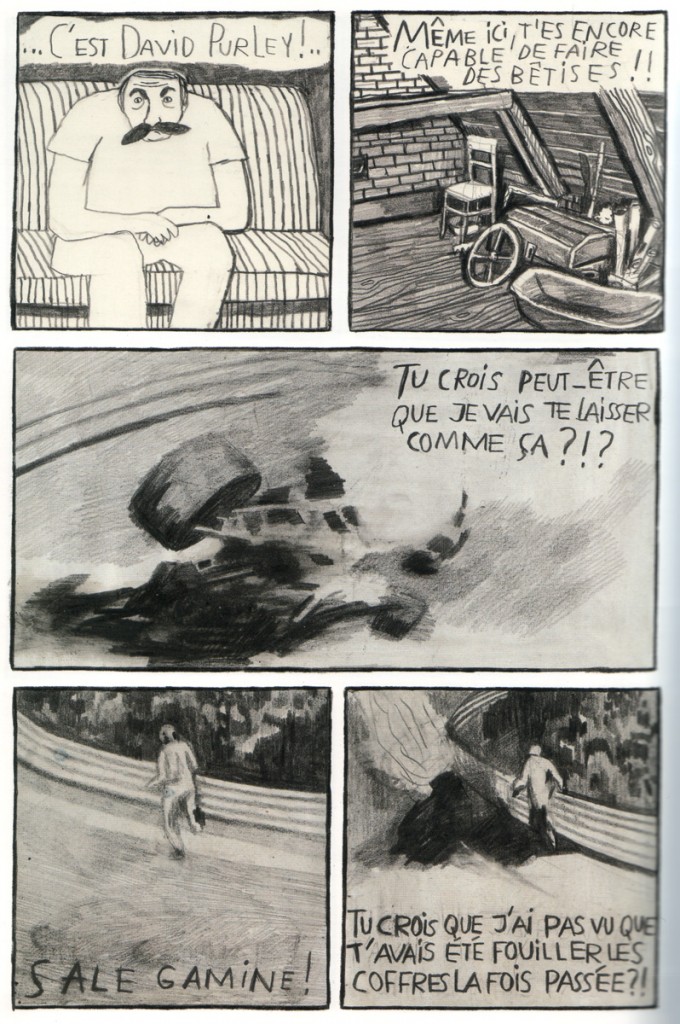

An oft cited criticism of this book seems to be that it slows down in the middle, full of repeated, barely distinguished events of horror or death. Yet that is exactly the point, Sacco blurs the lines between time and place, and places his event within the ongoing conflict. Rather than simply a distinct position in the past, he demonstrates its relevance through to the present. Through our reading of the book then, we begin to experience the blurring of memory and confusing of events which afflicts its subjects, the elderly refugees themselves. Throughout the book in fact, Sacco uses his composition to express not simply the facts of a scene, but the impressions of its subjects. Take this page for instance, where the contradictory viewpoints of the panels reinforces the confusion and chaos of the moment.

There seems to be a conflict here though, between Sacco’s drive and demand for truth which he confronts in the ‘Memory and the Essential Truth’ section, and the aforementioned projection of the event through the lens of blurred memory and confused experience. In one instance Sacco is railing against his unreliable sources, and trying to define the true account of various events, on the other he depicts those events with the very vagaries which he condemns. Sacco seems caught between two ideals, between the historian’s desire to uncover and visualise the ‘truth’, and the more artistic drive to depict events from the perspective of the subjects, to allow them to speak directly. Throughout the book this remains an unresolved conflict between truth and memory, as central a presence as the Israel/Palestine conflict itself, until Sacco leaves Gaza, and muses:

“how often I sat with old men who tried my patience, who rambled on, who got things mixed up, who skipped ahead,who didn’t remember the barbed wire at the gate or when the Mukhtars stood up, or where the Jeeps were parked, how often I sighed and mentally rolled my eyes because I knew more about that day than they did”

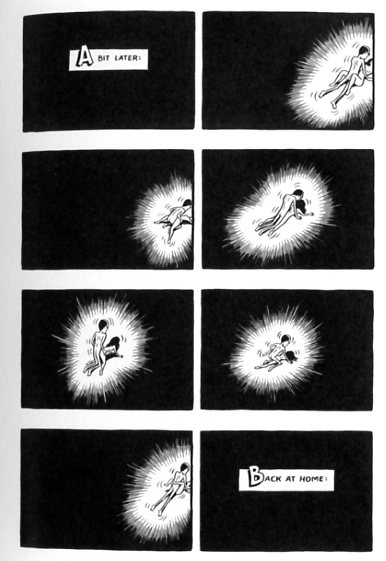

The statement is followed by the final sequence of panels, without words, depicting flashes of the events depicted earlier. They are confused and fragmented, with only a faintly observable narrative running through them.

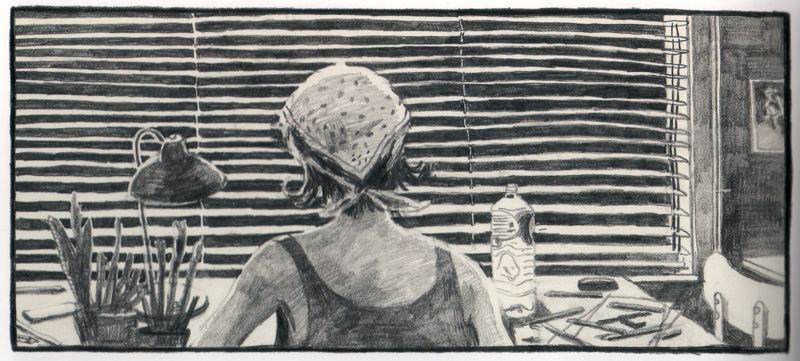

There is an acknowledgement here, that, for all that Sacco has become, as he says, “the worlds foremost expert” on the massacre of 1957, this book only constructs one narrative of many. That, despite the aim of writing the narrative of ‘the footnotes’, of the victims, Sacco’s book is simply his own narrative, his own interpretation of the collective memories of the victims. It’s an idea reinforced by one of the final panels, of Sacco staring, emotionless, across a boundary, at a grieving Palestinian man. The process of research for the book, the sifting and comparing of accounts, the search for the ‘definitive version’, ultimately separates us from the alternative narrative of the victims which Sacco originally intended. In the end Sacco has to some extent fallen into the same trap as the journalists and historians he rejects at the start of the book. His single narrative overpowers the individuals involved, and once again the Palestinian victims become footnotes to yet another (though admittedly more sympathetic), history.

Despite a conviction in his ‘essential truth’ idea, Sacco therefore seems to end by acknowledging his folly. He cannot combine an awareness of, and sympathy for, the individual with any kind of objective truth. Yet if the conclusion of a work of history is that history is subjective, then that only begs deeper questions. Aguably, Sacco’s commitment to his ‘essential truth’ causes an artificial distinction between history and empathy. Once we accept that we cannot draw an objective narrative from oral accounts of memory, once we accept that memory is not truth, then it seems a more interesting to ask, what is the actual relationship between memory and truth?

Halbwachs has argued that “It is in society that people normally acquire their memories. It is also in society that they recall, recognize, and localize their memories”. The point being that a social context both shapes and is shaped by memory. Arguably, here is the more interesting aspect of Sacco’s project, hinted at yet never addressed, eclipsed by the pursuit of ‘history’; memory is constructed, not only by social interaction, but by current experience, and vice versa. Thus the memories of the Palestinian refugees are influenced by the dominant narrative of society. As Halbwachs puts it, “society provides the materials for memory”. This narrative is not constant, but continually developing, and events in the present prompt re-evaluations of the memories of the past.

Conversely, as Sacco takes at face value the assertions of young Palestinians that they have no interest in the past, he fails to engage with the idea that their anger in the present is not simply a product of current atrocities, but also an unconscious product of an ongoing narrative of conflict. Their inherent notions of ‘we’ and ‘they’ are shaped by the dominant discourse as much as by physical events. Thus the connections between past and present which Sacco draws so clearly are not merely symbolic of the circularity of the ongoing struggle, but are themselves a factor in the production and maintanence of paradigmatic perspectives which shape both memories of the past, and attitudes of the present.

In a sense, what Sacco does is position his event within history, within temporal continuity. What he ignores however is its position within a social environment, the way in which events of the past become reduced to myth, their complexities subsumed as simply another example of the ‘them vs us’ narrative. Of course, not all history is required to take this deeper analytical view, and it is perhaps churlish to expect this level of insight from Sacco. However the use and reliance on memory in his methodology means that throughout the book we are constantly confronted with the flaws of memory, yet without a deeper investigation of its nature. If the objective truth of the events of 1957 is difficult to ascertain through memory, that is only the superficial conclusion. The deeper mysteries lie in how those memories are formed, and how they engage with not simply the reality of the now, but its dominant discourse.

____________

Ben is an itinerant and easily distracted Arabic postgrad who blogs about culture and comics here, and summarises Middle Eastern news here.