I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

—Wallace Stevens, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,

So what’s being compared here?

At first the answer seems fairly obvious; three minds are being compared to three blackbirds. When you think about it a little more, though, things get blurry. For one thing, the simile doesn’t quite map; the three minds are actually being compared to the tree, not to the blackbirds. So is there one overmind in which the three minds sit? Or is the tree the mind in which the blackbirds sit — or a number of minds, in which different explanations of the simile quietly caw? The poem doubles — or triples — back on itself; it seems to be describing or explaining its own processes. And if it’s talking about itself, the simile is there merely to multiply. The mind, the blackbird, and the poem are shadows that slide one into the other, each and each and each.

Or, to put it another way, the connection between the blackbird and the mind is arbitrary. That’s how metaphors work; they connect unlike things. Language is all metaphor; a string of arbitrary links, slipping signs that magically pull meaning out of non-meaning, like an infinite string of blackbirds rushing out of that tree, or mind, or poem. Wallace Stevens poems are built out of metaphors and think about metaphors, which is what I meant here when I said:

Wallace Stevens is very much about words. It’s words as imagery, but the point of most of his poems is the evanescence of those images; they’re arbitrary. They appear in language and disappear into language.

As a result, it’s not really possible — or at least very difficult — to create an illustration that works like a Wallace Stevens poem.

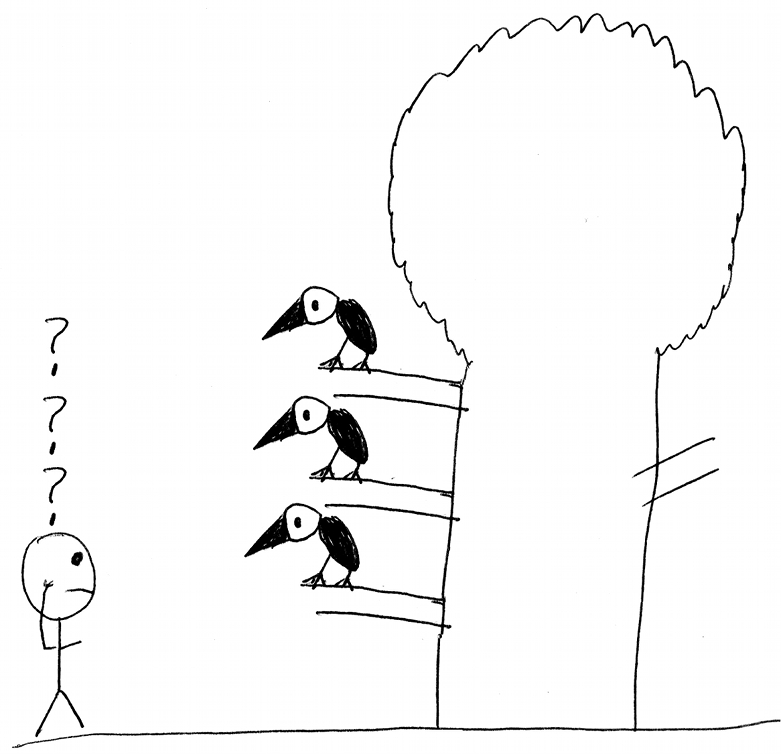

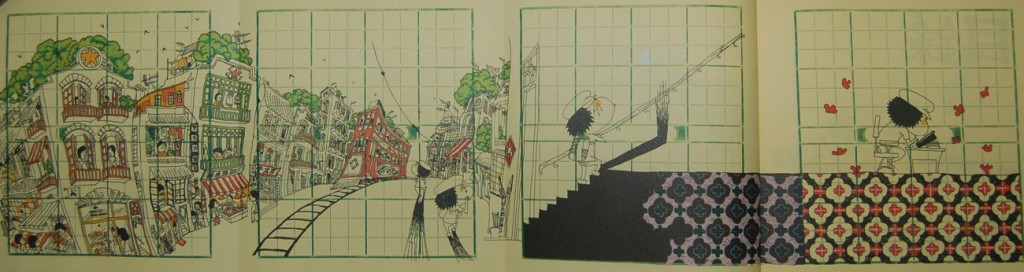

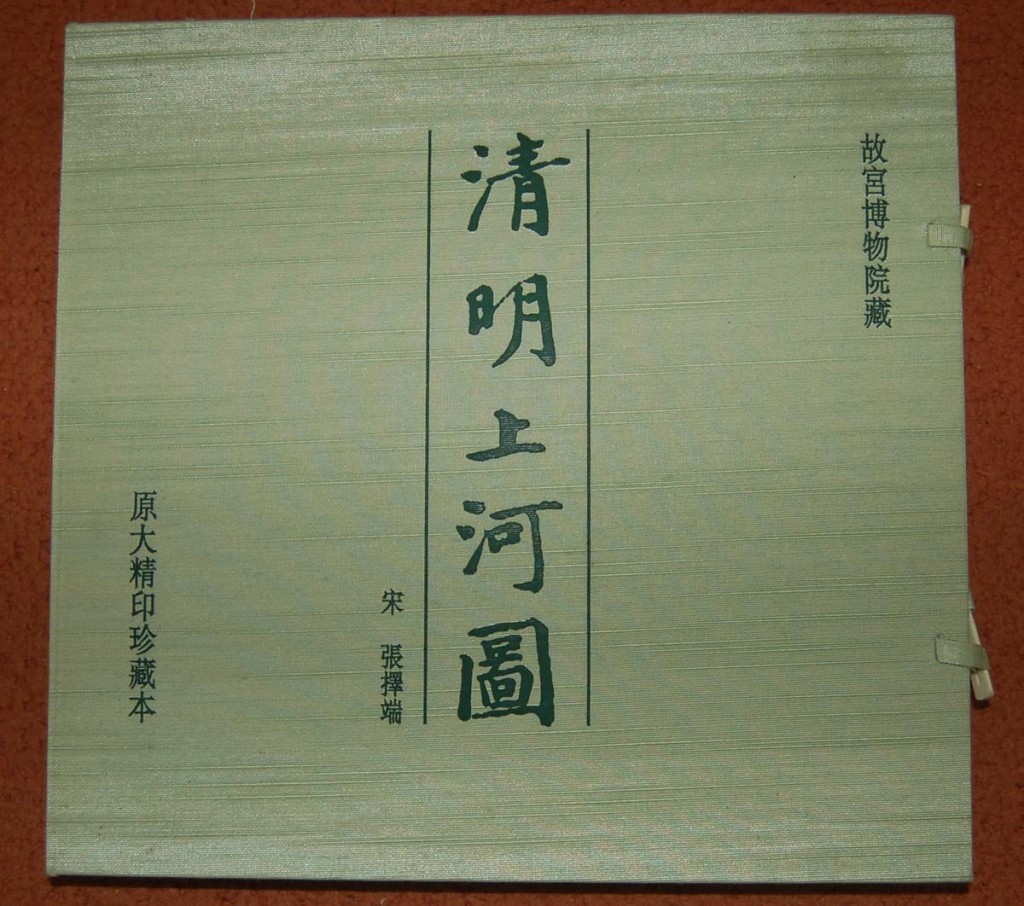

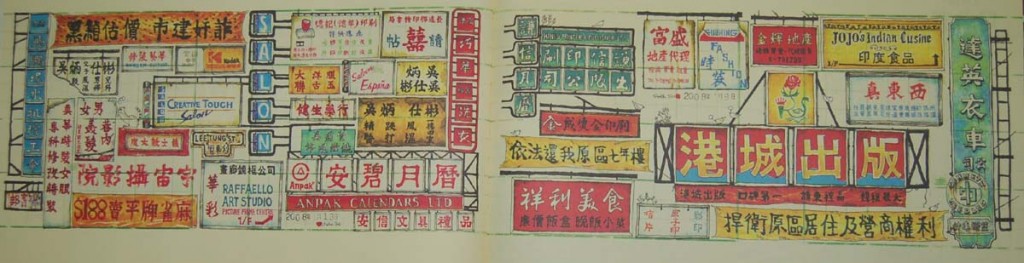

Though, of course, there isn’t anything to stop you from illustrating a Wallace Stevens poem. Nothing simpler. Here’s my own illustration of the above poem, taken from a zine I made way back in 2002.

This drawing neatly reverses the poem its illustrating. In Stevens, the mind comes first, and then the image of the blackbird follows. But in the illustration, the blackbirds are as solid as, and essentially precede, the split consciousness. Instead of three minds generating three blackbirds, the blackbirds generate three minds, represented by the chain of question marks. The poem spins an epistemological conundrum (what do I think?) into an ontological one (where are the blackbirds?) The illustration, on the other hand, takes an ontological question (what is the status of these multiple, poorly drawn critters?) and spins it into an epistemological one.

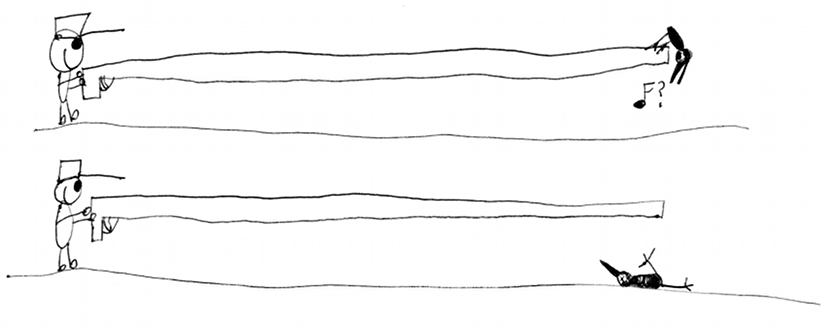

Here’s another example:

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

Here, the illustration’s concreteness doesn’t so much mirror the poem as parody it. The poem treats the blackbird’s insubstantiality as sublime; the word is beautiful because it shimmers and passes; the singing depends on the silence and the silence on the singing. The illustration, by nailing down the ephermerality, reimagines it as (or teases out the implication of) violence. Language’s play is freedom — what separates us from the blackbird is that we can contemplate the blackbird. But that (loooooooooooooong separation) from the animal is also our knowledge of sin, which is the knowledge of death. The poem is about the joy of the world slipping into words. The illustration is, maybe, a reminder that, from the perspective of the blackbird, human mastery of the world may have a downside.

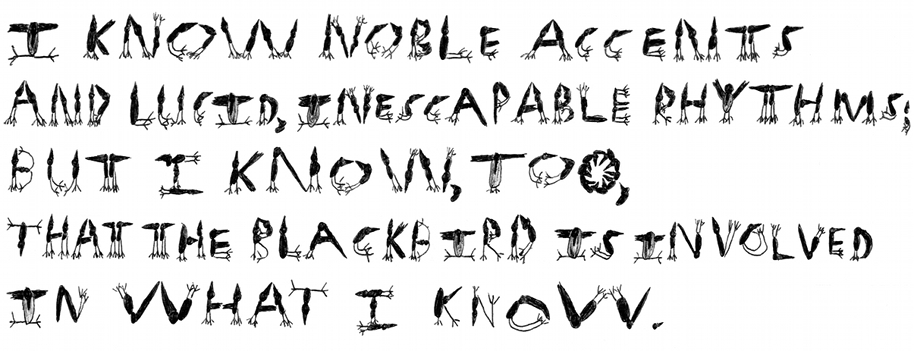

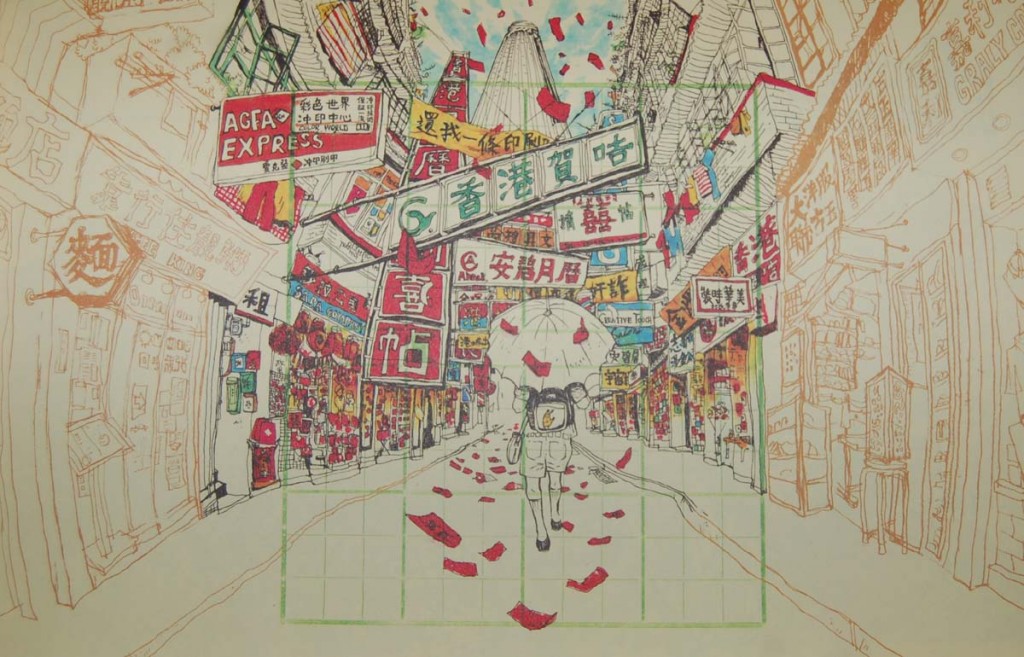

One last one…and here, I think, the illustration and the poem really do come close to meaning the same thing.

In “Thirteen Ways,” the blackbird stands in for both sign and signified. It’s the mark that points and the thing pointed to; the trace of a reality that can be indicated but not reached. The poem above can be read, perhaps, as an acknowledgement that words are not a self-contained system; the world is in there too, even if we can’t really tell exactly where. If words coat our images, then maybe images infest our words. We speak blackbirds — or at least something that looks a little bit like them.