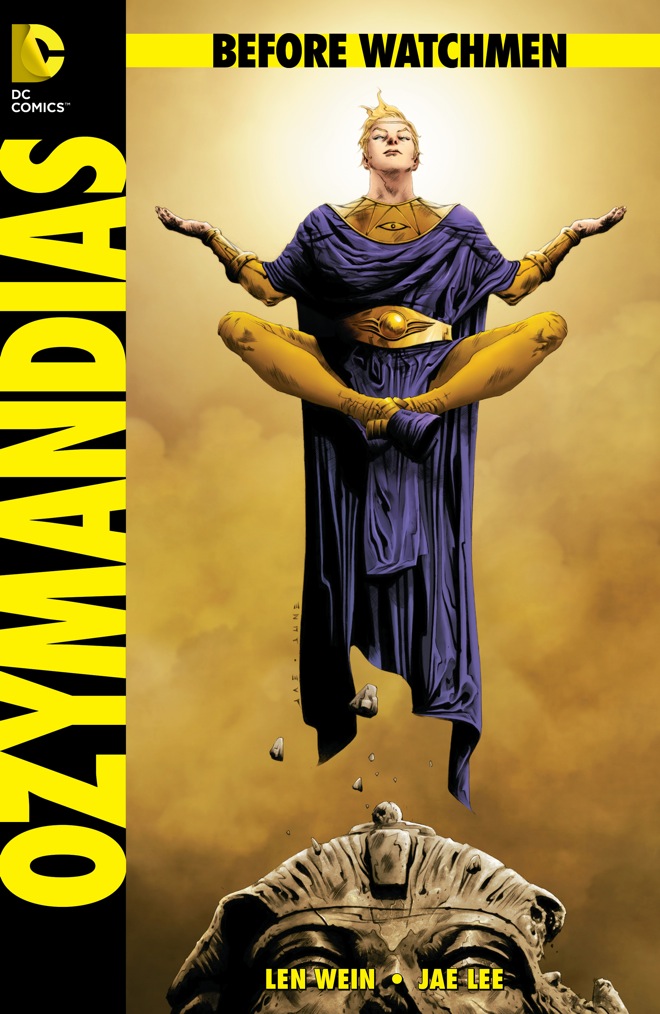

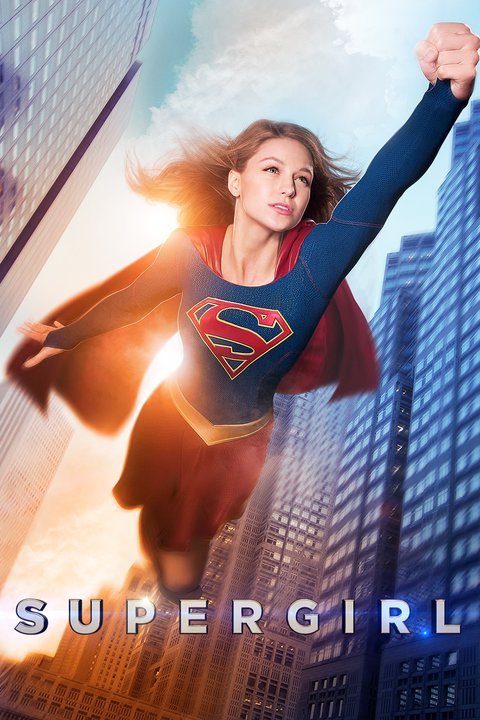

Some of my favorite comics growing up were the oddball superhero pairings Marvel would throw together: Spider-Man and Scarlet Witch, Thing and Black Widow, Thing and, well, Thing (that was an odd issue). So I’m delighted that the marvels of the publishing universe have thrown together my two most anticipated new books with the same fall 2015 release: Lesley Wheeler’s Radioland (Barrow Street Press) and my own On the Origin of Superheroes (University of Iowa Press).

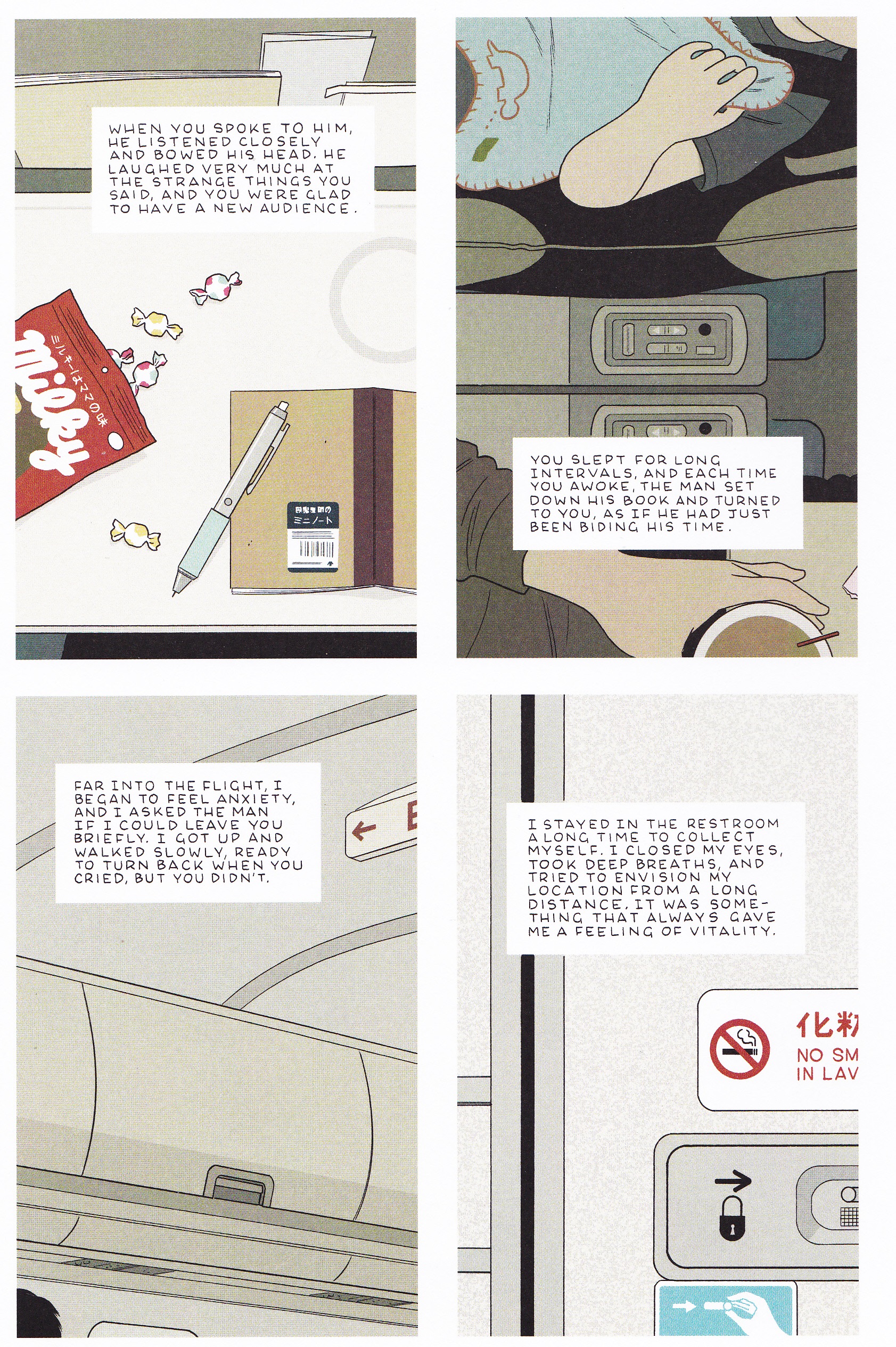

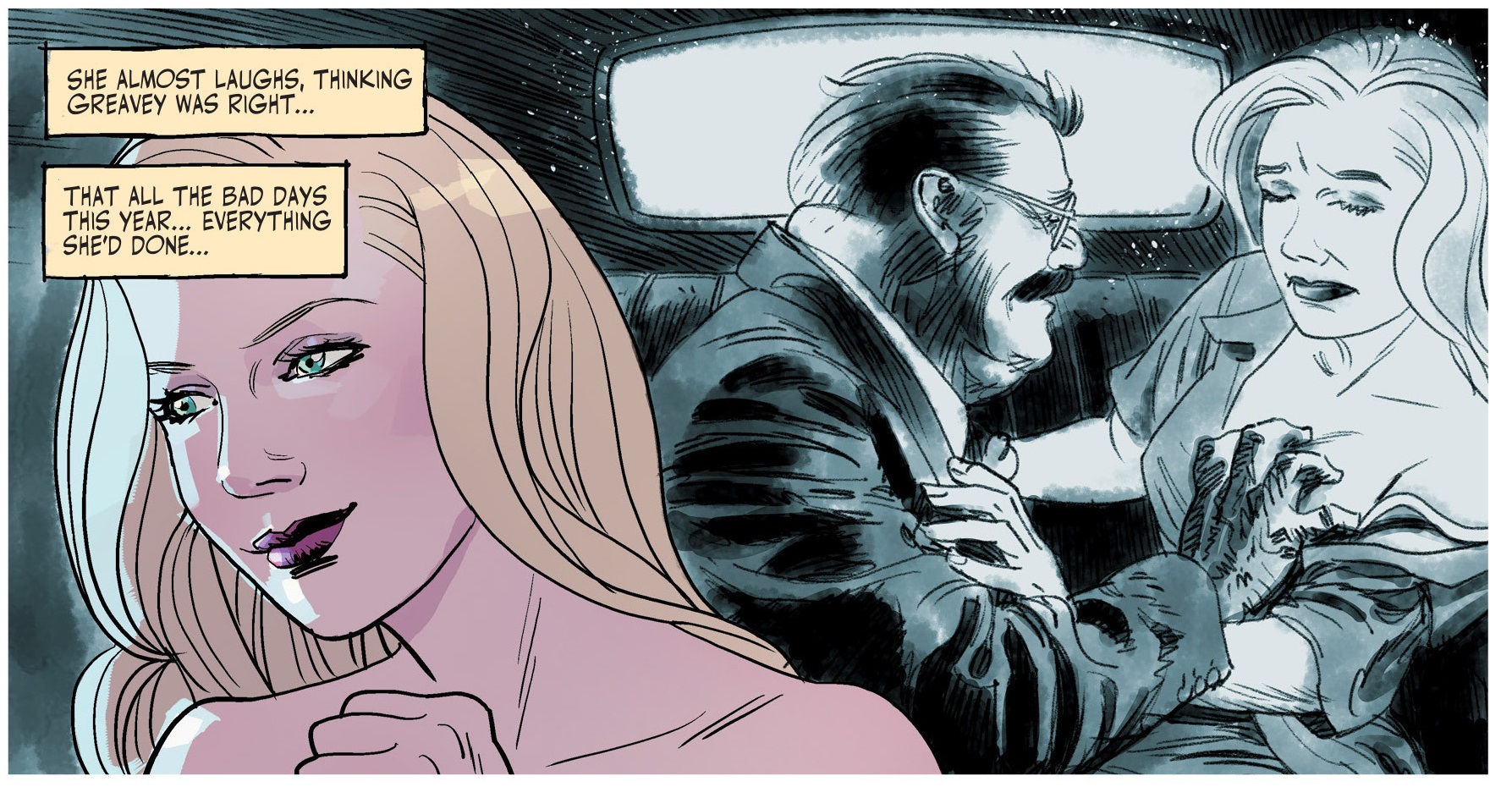

Obviously I’m anticipating my own book. Publishing means organizing readings, reviews, interviews, and every other kind of publicity. But it’s the poetry collection Radioland that I’ve actually looked forward to, that I can now sit back with a pre-release copy in my lap and sincerely admire. I already read it in multiple manuscript print-outs, but there’s nothing quite like the authoritative aura of a glossy-covered book fresh from its publisher’s packaging envelope. I’ve read all of Wheeler’s previous books (her scholarly Voicing American Poetry and The Poetics of Enclosure, and her collections Heathen, Heterotopia, and The Receptions and Other Tales), but Radioland is my current favorite. And not just because I teared up when I opened to the surprise dedication:

for Chris Gavaler

and other good fathers

I should acknowledge that I’m Wheeler’s spouse. We’re professors in the same English department too, so our professional identities team up constantly. But you never know which student or non-departmental colleague is going to give a startled blink at the discovery of our two-in-one domestic life. Aside from our three-sentence wedding invitation, we’ve officially collaborated on only one scholarly article (about poet Marianne Moore) and two children (a first-year in college and a first-year in high school). But our co-editing is invaluable.

After dutifully reading my weekly superhero blog, Wheeler saw me through the surprisingly complex process of rewriting and reorganizing the pre-1938 material into a cohesive manuscript. When an Iowa acquisition editor read the blog and contacted me to ask if I wanted to convert it into a book, I said yes. Obviously. But it was Wheeler who suffered the first drafts of each reconceived chapter, helping me rethink, rework and eventually refine. As I explain in the penultimate paragraph:

>Lesley Wheeler has no superhero scholarship I can cite either, but she’s seen me through each step of creation, critiquing everything from the first harebrained draft of that KKK essay to the thorniest midtransformations of this manuscript.

I dedicated my first romantic suspense novel to her (Pretend I’m Not Here is even set in the Virgin Islands where we honeymooned). But On the Origin of Superheroes is dedicated to John Gavaler, my father. He read comics as a kid in the 40s, fueling my comic book reading in the 70s. John is also one of the “other good fathers” of Lesley’s book dedication, a category that, when you read the collection you’ll see, doesn’t include her own. He’s more like the supervillain Nightmare haunting her sleep—no matter how many times she vanquishes him in real life. But her poetic superpowers more than make up for his failings when Radioland single-handedly realigns the universe into a better shape. “Gods and fathers,” her final poem concludes, “rarely signal / but rock vibrates /sympathetically. What else / could it say? Echo / a kind of love . . .”

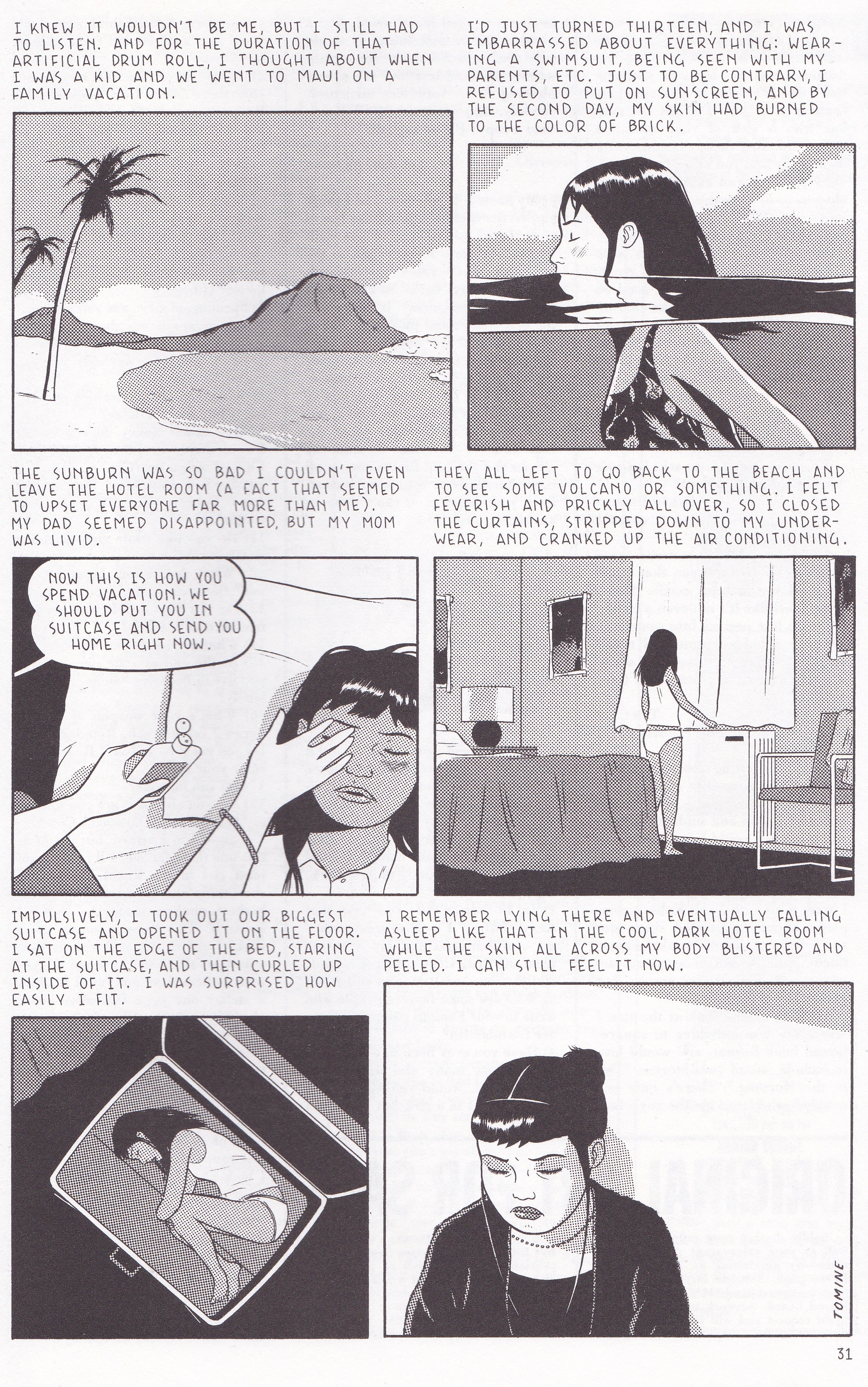

Wheeler and I also appear together in last year’s superhero poetry collection Drawn to Marvel: Poems from the Comic Books, but our most superheroic successes are our kids. Oddly, that includes standing on the crumbling planet of their childhood and watching them blast away in private rockets. Madeleine is now adventuring in the distant solar system of Connecticut, and Cameron, while still homebound, is tearing Hulk-like through his adolescent wardrobe, poised to make the same single-bound leap into adulthood.

Meanwhile, we have our books. Not as brilliant and hilarious as flesh-and-blood children, but they are easier to read and to hand to a friend.