The index to the entire Joss Whedon roundtable is here.

_________

“We make choices. I’m well aware there are forces beyond our control, even in the face of those forces we make choices.” – Adele, Dollhouse

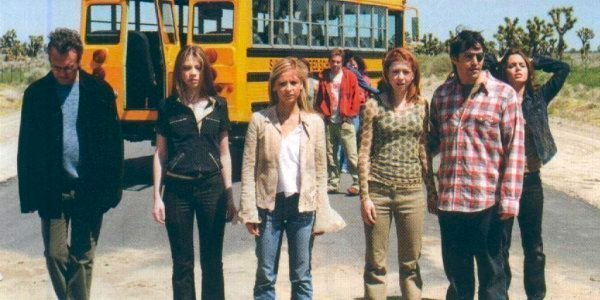

Given the recent contention surrounding Joss Whedon’s brand of feminism, we immediately wanted to revisit Dollhouse for this roundtable because of how far it takes some of feminism’s central concerns (and also because of how much feminists seem to hate it). We decided to structure our analysis of the show as a dialogue for two reasons. The first was simply to approximate the feeling of an informal roundtable, and the second was to side-step the is-or-isn’t-this-show-feminist quagmire by modeling the ways in which feminism, like popular culture, is dynamic. All it can offer us a place from which to start—not settle—discussion.

Desirae: I suppose I’ll address the is-or-isn’t-Dollhouse-feminist thing by saying that there are many different types of feminisms, and they are all going to have a different take on the show. Dollhouse is fundamentally concerned with philosophical questions relating to freedom, choice, and the self, and different feminisms relate differently to these things. So when people say Dollhouse is a rape fantasy or glorifies sex work, my thing is that perspective specifically comes from liberal feminism, which has to believe in (and so wants to see reflected) this idea that women can be free and empowered with choice. This is why consent is such a huge part of liberal feminist rhetoric. But if you’re dealing with a system of complete control that sort of consent (Yes, I choose my choice) doesn’t make sense anymore because there’s no choice that isn’t coerced in some way. I think that’s the main premise of the show, and it’s exemplified by the Dollhouse itself… but it’s also meant to be a reflection of the world in which we live.

Jade: Yeah, which is why it’s such a cool premise. The fact that in S1 E6, in the beginning stages of developing her own awareness and while imprinted with another consciousness, Echo chooses to complete her engagement after it had been interrupted by Paul’s white-knighting. Echo seems aware that her imprint didn’t experience resolution, and that the romantic engagement hadn’t been executed to completion. Does her choice not matter because Caroline (or her “soul”) isn’t present? I guess that’s a metaphor for intoxication or other forms of out-of-body-ness that liberal feminism would argue cannot be consent. Caroline consented to being a doll; she signed the papers…but liberal feminism wants Caroline’s consent in the moment. S1 E6 is the first moment where Echo asserts her will which forces us to ask, what the threshold that has to be crossed in order for something to count an authentic choice.

In another scene, Paul argues that you can’t erase a person’s soul. He later doubles down on that when he refuses to sleep with Echo because all her actions, desires, and sexuality are programmed. As a result, he thinks she cannot consent. This idea that we are only able to TRULY make a choice if there is a connection between our mind, our body, and our soul speaks to the “ghost of Christianity” that lurks in all Joss’s meditations on “the soul.” It fuels the critiques of Dollhouse as rape fantasy and completely ignores that we are all products of coercion. The systems we live within are deeply ingrained in the very nature of our bodies, minds, and souls, and taken to its most extreme conclusion: all sexuality is rooted in coercion, especially unexamined heterosexuality.

D: Right, and one way of looking at it is, how is our daily reality different from the dolls’? I think I can genuinely choose or consent to certain actions/relationships, but there is a larger structure of systemic coercion that doesn’t allow me the choice to not engage, you know. Adrienne Rich called it “compulsory heterosexuality,” where choosing to opt out isn’t really an available choice. Even if you’re a lesbian, you’re still acting within a system of compulsory heterosexuality. In this scenario, I feel like a doll.

J: I do too. We agreed to keep this focused on S1, but the fact that the first episode of S2 is about a long-term engagement where Echo gets MARRIED could be discussed at length. It’s just wonderful.

D: My body is coerced in various environments and ways, and there’s no way I can consent to some of what I choose to do. Like that is the literal definition of oppression.

J: Right. All the people in the Dollhouse were coerced, even those that chose it. Caroline, Madeline, and others are seen signing contracts and while they do, we hear Adele’s well-crafted explanation of the Dollhouse’s purpose (and its benefits). We’re to believe they understood the terms and accepted them. They’ll wake up in 5 years with a clean slate—selective memories removed, PTSD treated, and free of the guilt that they had before their residency. It isn’t until the S1 E8-where they are allowed to live out their “needs” as a way to correct the glitches each doll is experiencing that we discover that there’s an element of coercion to everyone’s decision to enter the Dollhouse. This exercise relies on the same idea Paul sells later, that you can’t completely remove the fundamental need of the original personality’s soul.

D: Which was itself a thing they were allowed to do by Dr. Saunders and the Dollhouse. There’s no real consent in the Dollhouse, but there’s no real consent anywhere else either. And that’s what the show problematizes, and I also think it’s a thing that a lot of mainstream feminism does not want to have to confront politically. No, your desire isn’t authentic. No, you are not free. But that’s just what it means to be a person in the world.

J: Well, and Priya is really the only character who didn’t consent to entering the Dollhouse. She’s the only one who was trafficked in. Her residency in the Dollhouse is painted very differently than Caroline, Madeline, and Anthony. While you can argue that Adele emotionally manipulated the others into joining, with Priya, it was Adele that was manipulated. Priya is drugged into an altered state and misdiagnosed with schizophrenia, which Topher thinks he could treat through the active architecture.

D: That’s interesting. There are a lot of instance in which people step on the autonomy of others, even if they have good intentions in doing so.

J: Yeah, Echo and Paul are trying to “save” everyone. In S1 E8 in the midst of Caroline’s rebellion against the Dollhouse Adele says to her, “You are free to leave. Who are you to decide for the others?” It’s like liberal feminists or white knights that try to save women from whatever “bad decisions” we make, whether it’s wearing make-up or engaging in sex work… And Adele, Caroline, and Paul are representative of different savior scenarios. Paul takes the patriarchal approach and asserts that there is only one way to be authentic. Adele is the champion of individual choice. She believes in a world where empowered choices can be made freely and she asserts and protects people’s ability to do so. Caroline is an animal rights activist who has good intentions but often can’t see how her actions hurt the people around her. Dollhouse stages these different types of problematic commitments to social justice and challenges us to question the idea that there is One Best Way to address oppression.

D: They all choose for other people; that’s what saviorism is. It’s also what rape is. Back in 2009, i09 ran an article that drew a direct line between rape and the dystopic future the Dollhouse’s technology creates. It’s not an accident that it all started with some savior impulse…

J: Though, we do see instances of authentic and real decisions, like Victor/Anthony and Sierra/Priya. They develop a relationship in the doll state that isn’t consented to, but later Priya falls in love with Anthony. We’re meant to trust in and support their relationship.

D: Yes, but even that one is weird. Doll-state Sierra (who is Not Sierra) doesn’t consent to her relationship with Victor, but that love is cast as being the only authentic one in the show. It’s as though the Truth of their connection transcends the doll state and carries into their original personalities. I think that goes back to the idea of the soul that you keep bringing up. We want to think there are these hard kernels of the self that can survive all the coercion and the ideological programming that structure our daily lives; Victor and Sierra, apparently, have that kind of love. But is it really that different than the relationship between, for example, Adele and Roger (an Active)? Paul and Mellie (an Active)? Paul and Echo (an Active), and then later Echo (who has become a self) and Paul (who becomes an Active)?

J: So here’s a question: once Echo becomes self-aware, does Caroline have the right to essentially kill her by taking her body back? What about active imprints within Echo? What happens to consent then? We are to believe Caroline has that right as the “true owner” of her body. Toward the end of S1 and into S2 as each character becomes self-aware, we see another set of circumstances that pit informed consent against coerced choice, and the ways that the system forces everyone’s hand. This is most clear in Madeline’s case. She is released from her contract because Paul agrees to become Echo’s handler in order to play out his fantasy of “saving” Caroline. (Which is eerily similar to some of the Dollhouse’s clients’ paid engagements.) Later, when Madeline’s freedom is tested, she tells Paul that freedom means the ability to make choices even if they’re the wrong ones, and she asks if she is really free. Paul, who so desperately wants to believe in freedom beyond the Dollhouse, (again!) grants that freedom to her (which speaks to his patriarchal saviorism, he allows the “bad choices” to happen). And of course it’s the “wrong” choice and Madeline ends up back in the Dollhouse, this time as a prisoner—no consent. And then of course, Echo, who is being driven by Caroline’s savior soul, stays to fight. So you’re right, at the end of the day there is no choice that proves to be correct or any less coerced. Whether any of them chooses to stay or go, fight or comply, it’s all equally a matter of acting out what they are programed to do—whether literally by the Dollhouse or figuratively by an inborn sense of ethics, duty, or whatever.

D: One of the ideas we’re touching on too is, what are the limits of capitalism? Can you, for example, sell yourself into slavery? That’s one of the show’s major questions. Is the self a thing that can be bought and sold? If so, who owns it? We were talking the other day about how saying that all choice is coerced can be deployed in super racist ways (see: Meghan Murphy’s take on Laverne Cox’s babely photo spread in Allure). So there is a way in which the conversation needs to be attuned to contemporary and historical differences in raced experience… because there is a difference between “selling oneself,” which is the term liberal feminists often use for sex work, and being sold as chattel by another. Think the difference between Dominatrix Echo and Priya being trafficked into the Dollhouse. In liberal feminist rhetoric, these are the same thing. But in Dollhouse, we are meant to see the difference between Caroline’s choice to become an Active, which was an abdication of responsibility, and Priya’s being trafficked into the Dollhouse, which was a violation of sovereignty. So all of this is to say, in my mind at least, that if all choice is coerced then no one choice can be better or worse than another. But at the same time, just because all choice is coerced doesn’t make all coercion equal. These are distinctions that I think are missing from feminist critiques like Meghan Murphy’s or those that reduce Dollhouse to a rape fantasy.

JD: So, I like the idea of ending this with a quote from Boyd. I feel like it kinda brings everything home.

D: Yes, I agree, especially because of the role that he plays in the show, going from handler to arch villain.

J: If we had more time I’d go into detail about that ep because it’s a mirror of the Dollhouse, but it comes from S1 E5, “True Believer,” which I think is a self-contained examination of the entire premise. “No one asked to be saved—not by you.”

____________

Jade Degrio works in the fashion industry and is a freelance writer for various online and print publications. She specializes in yelling about things on the internet

Desirae Embree is a PhD student in English at Texas A&M University, where she has figured out how to make watching too much television a (somewhat) respectable profession.