France has its own Batman. He’s named Nightrunner, and he’s been patrolling the streets of Paris since 2011 when DC introduced him as part of Bruce Wayne’s Batman Incorporated team. I walked some of those streets in June, but I didn’t see any caped crusaders, just used book vendors lining the Seine. A few of them sold BDs (bande dessinee, “drawn bands”), mostly late 70s and early 80s stuff, stray Teen Titans and X-Men between stacks of Tintin and Asterix.

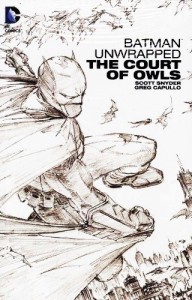

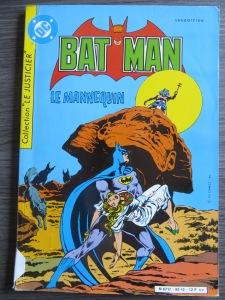

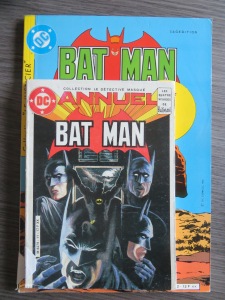

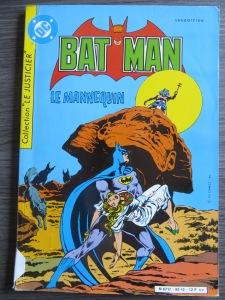

The Bronze Age Batman belonged to the French publisher Sagedition. I found him in the Angouleme research library while tracing the influence of U.S. superheroes on their French counterparts. The cover title story, “Le Mannequin,” doesn’t match the cover image,”Le Secret du Sphinx” (I’ll let you translate both of those yourself) because the issue collects five Batman adventures in what was not yet popularly called a graphic novel format.

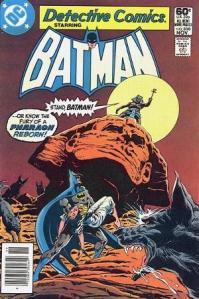

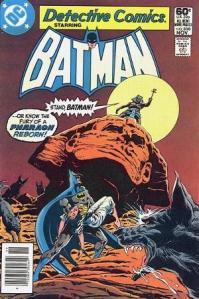

Note “LE JUSTICIER” printed along the left margin; it roughly translates, “THE ADMINISTRATOR OF JUSTICE” (a mystery we’ll return to soon). Otherwise the cover is Detective Comics No. 508, minus artist Jim Aparo’s growling dog in the foreground (deleted, presumably, by the French censorship board):

The Sagedition version is cover-dated December 1982. I cross-referenced the content as Detective Comics Nos. 506-510, the last episode from January 1982, so roughly a one-year turnaround time. Unlike the original American publications, the translated reprints include no advertising, not even on the back cover; the inside front and back covers are blank, with an added table of contents and very brief publishing information on the final page.

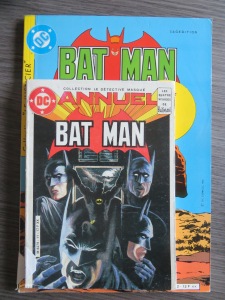

Sagedition also printed only half of the pages in color. Turn a page and you’re looking at a black-and-white, two-page spread; turn again and it’s a color spread. This presumably saved printing costs, though I found the alternating color system dates back to the tabloid-sized newspaper BDs of the 40s. Sagedition applied it inconsistently. A 1985 Batman “collection un max” alternates its first 98 pages, before switching entirely to color for the last, re-paginated 45 pages (which also include an incongruous Golden Age Dr. Fate/”Dr. Destin” adventure). A 1986 Batman and Superman omnibus prints all 96 pages in black and white and in a smaller format:

Smaller, black-and-white pages may also reflect Sagedition’s shrinking business. The company vanished in 1987.

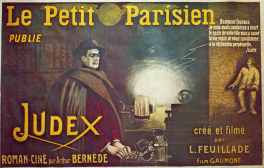

France has no Silver Age Batman. The BD censorship board (the Commission for the Oversight and Control of Publications for Children and Adolescents) established by the Law of July 1949 effectively halted the importing of most American comics. But just prior to the law’s passage, French readers had two Golden Age versions of Batman. Beginning from its first September 19, 1946 issue, the weekly 8-page tabloid Tarzan included “A Chauve-Souris” (the surprisingly multi-syllabic French way of saying “A Bat”):

And beginning with its first May 21, 1947 issue, L’Astucieux ran “les ailes rouges” (“the red wings”) on two of its eight pages, including an interior page in black-and-white which continued to the color back page:

Despite the title change and the red cape and cowl, Batman is still called “Batman” in the translated dialogue.

Both Batmen vanish in 1948 as criticism of American comics and their influence on France’s BDs was building toward the censorship law. U.S. comics publishers faced similar criticism at home but created the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers to stave off legislation. The ACMP’s 1948 code went unenforced until 1954 when it was revised and adopted by the new Comics Code Authority in the U.S. industry’s second maneuver to avoid government regulation. The British Parliament passed its own comic book censorship law in 1955.

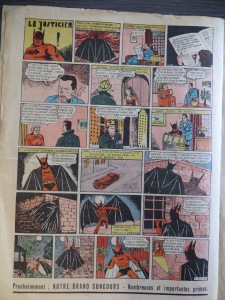

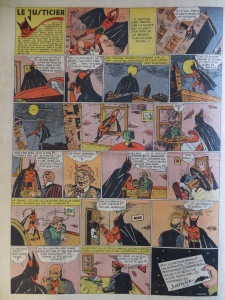

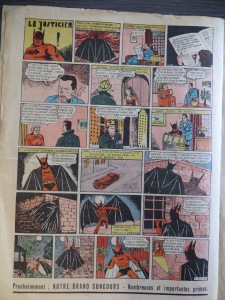

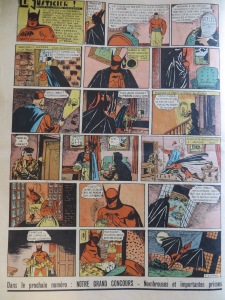

In all three cases, the call for censorship was a post-war cause. Batman appeared only once in France during World War II. Germany invaded in May 1940 and by August divided the country into an occupied northern region and the so-called “free zone” of Vichy France. The weekly Les Gandes Aventures premiered the following month. Beginning in the tabloid’s second issue, “Le Justicier” ran through October and November in eight weekly pages, divided into two, four-part stories. The first is an uncredited adaptation of Detective Comics No. 30 (August 1939), Batman’s fourth episode, written by Gardner Fox and drawn by Bob Kane with Sheldon Moldoff co-inking.

Les Grandes Aventures, No. 2:

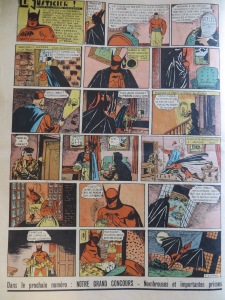

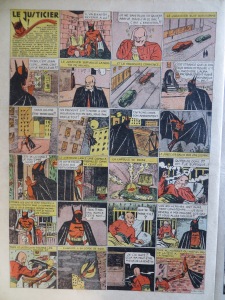

Les Grandes Aventures, No. 3:

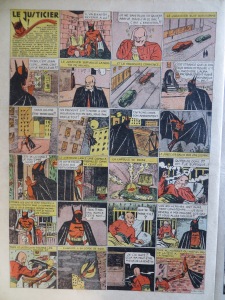

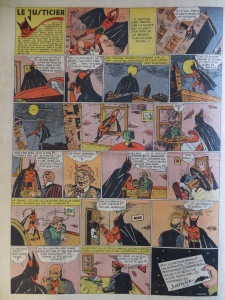

Les Grandes Aventures, No. 4:

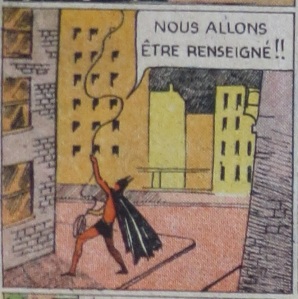

Les Grandes Aventures, No. 5:

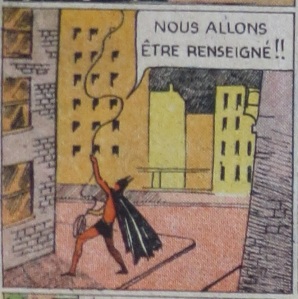

Unlike Batman’s post-war appearances, Les Grandes Aventures does not reproduce the original artwork, but redraws it panel by panel. To accommodate the differences in formats, the French version regulates panel sizes while usually widening Kane’s taller originals:

In order to conclude the adventure at the bottom of the fourth page, two new panels were added, including one of the worst drawn images in the sequence:

It’s difficult to judge what impact the Les Grandes Aventures Batman had on later French incarnations. His rouge costume is not quite the same as L’Astucieux’s Red Wings, though the inclusion of “Le Justicier” in the Sagedition reprints could be an allusion to Batman’s first appearance. But the term could also be generic, an equivalent of “vigilante.”

The Gardner Fox script features a thug named “Mikhail,” who, though identified as a “Cossack” (so Russian or Ukrainian), wears a fez and hoop earrings. He replaces Dr. Death’s previous thug, “Jabah,” a “great Indian,” who Kane dressed in a turban. Both Jabah and Mikhail wear cummerbunds, green leggings, and purple capes–a result of the printer’s limited color choices and Kane’s limited lexicon for his Exotic East. Batman kills them both.

Fox doesn’t mention Jabah’s and Mikhail’s religious affiliations, but the fez suggests Muslim. It brings us back round to Bilal Asselah, AKA Nightrunner, AKA the Batman of France in the international Batman Incorporated. Creator David Hine explains his choice: “The urban unrest and problems of the ethnic minorities under Sarkozy’s government dominate the news from France and it became inevitable that the hero should come from a French Algerian background.”

Some conservative bloggers weren’t happy with a Sunni Muslim Batman. Warner Todd Huston accused DC of “PC indoctrination,” complaining that “Batman couldn’t find any actual Frenchman to be the ‘French saviour.'” “How about that,” writes Avi Green. “Bruce Wayne goes to France where he hires not a genuine French boy or girl with a real sense of justice, but rather, an ‘oppressed’ minority.”

I consider Bilal reasonable reparation for Dr. Death’s henchmen, as well as a nod toward the actual Algerians who did fight as French saviours during the German occupation. They administrated better justice than the first French Batman, a pirated, second-rate feature from a publisher working under Nazi rule.

I’m glad Paris has a new Le Justicier.