It’s been a whirlwind week or two here at the Hooded Utilitarian for discussing race in comics. Building on earlier treatises about Black Panther’s exercises in assimilation narratives, Black Lightning’s equivocation on race and the X-Men turning black Noah Berlatsky asserted that the original Milestone Static comics kind of suck. J. Lamb argued that the superhero genre is fundamentally white supremacist, which makes most all black superhero characters generally useless.

As a black comics fan, this is abjectly depressing.

Everyone knows that black comic heroes hardly register as competition against white heroes for popularity. They barely exist. The fact that having one non-white costumed character on the big-screen is typically seen as an enormous boon for diversity is pretty demoralizing. When you add this to the fact that, as J Lamb wrote, non-white heroes function “within a paradigm defined by Western perspectives on violence and ideal beauty, in an industry dependent on White male consumer support .” I’m left feeling outright bamboozled.

The truth wouldn’t sting so much if these essays were written some time last year, but they just reaffirm what I had concluded after reading All-New Captain America #1. One of the most banal, vapid comics I’ve ever read, All-New Captain America#1 truly underlined the utter fecklessness of the black super hero. We have Sam Wilson, the first African American super hero in the role of Captain America with all of the variant covers and implied importance that the role suggests, adorned in the American flag boasting a triumphant reach to the utopic mountaintop, published within twelve days of the announcement that Darren Wilson would not be indicted for shooting Michael Brown. The book’s lack of self-examination makes the juxtaposition painfully jarring.

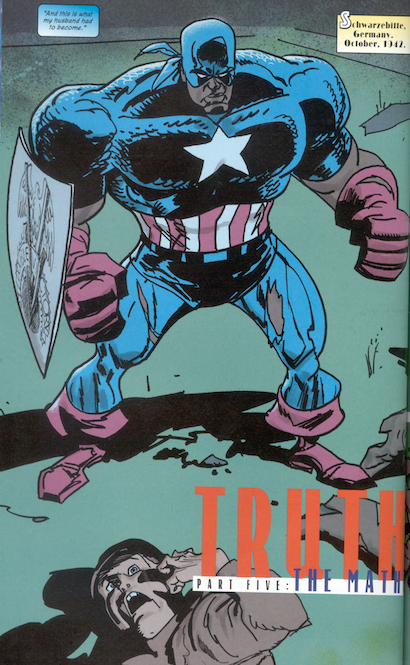

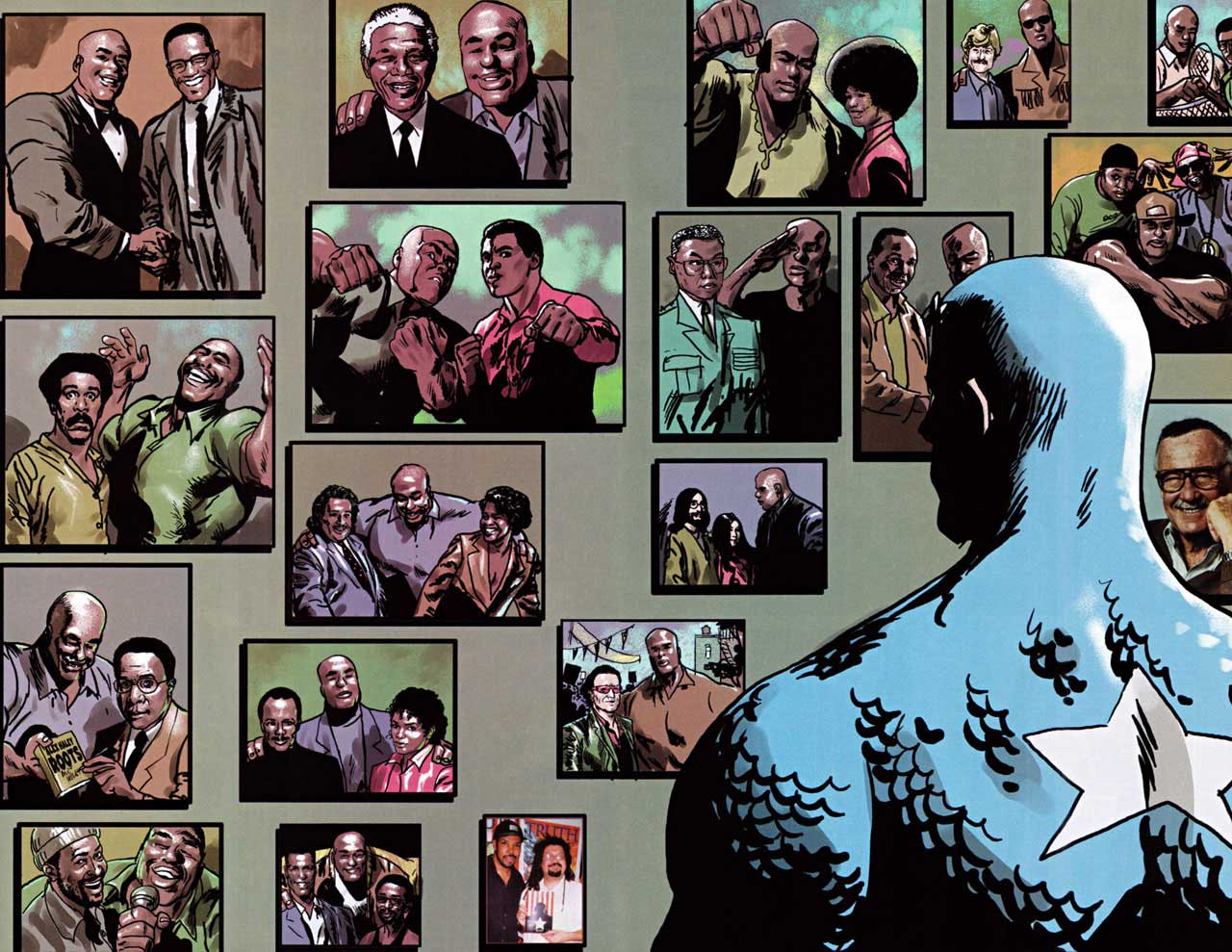

It isn’t as though I had ambitious hopes for the new Black Cap book. But I honestly thought the idea of a black Captain America would mandate a minimal degree of content, especially with books like TRUTH in Marvel Comics’ rearview. In this series, we’re presented with pages of wintry, hoary dialogue where Sam Wilson briefly recalls the death of his parents whilst dodging gunfire for no reason. He battles Hydra and fights Batroc, the French stereotype in a typical superheroic battle that is requisite for a Captain America comic, I suppose. However the concept of a black Captain America and what that means to him or anyone is completely passed over for an adventure typical for white Steve Rogers. The issue eschews moments of reflection from Sam, opting instead to toss in empty critiques of America’s obesity problem and government corruption. Remarks by the villains on how Sam’s nothing more than a sidekick are carefully worded; the reader can infer racial bias if he or she feels like it, or ignore it if the idea of a villain being racist is too upsetting or unpleasant.

Exploring the importance of Sam’s new role should be a no-brainer. Why else was an irrelevant Joe Quesada ushered back onto the Colbert Report to promote the book? Comic readers understand diversity is often an empty gesture in comics, but this is “Captain America”. I had no real fantasies about Sam talking about systematic racism or making birther jokes, but that the book literally says nothing about how the figure representing America as its premiere superhero is now black reveals how ruefully optimistic I was when expecting comments on the black super hero’s existence from a white writer.

The disappointment isn’t just mine. Writer and Public Speaker Joseph Illidge wrote about the first issue of All-New Cap on his weekly column for Comic Book Resources, “The Mission”. When reading it, you get the sense that he’s holding back a deeper sense of disappointment than he’s letting on. Lines like “I’m not going to make this a polemic on non-Black writers writing Black characters, because the dialogue on that subject may very well be reaching its golden years. That said, I would have preferred a Black writer handling this book.” Reading that, I can’t help but see an image of eyes clenched shut and a setback induced sigh.

He mentions the HBO series “The Wire” and says how it was a show where white writers presented black characters with a strong sense of authenticity. Illidge labels “The Wire” as an exception, and reiterates that white writers will almost always miss out on the nuances of the black experience. In the 50+ to 75+ years of Marvel Comics’ history the company has been generally viewed as the more diverse universe when compared to DC. Surely at some point, in all that time, one of those characters managed a convincing portrayal of the black experience.

As J Lamb wrote, black heroes can only do so much within the confines of the white establishment they exist in. Luke Cage may get his origin story from wrongful imprisonment and Tuskegee-inspired experimentations, but he won’t spend his super hero career warring on the treatment of black people by white authority. But it’s with relief that I recall a series of issues during Stan Lee and John Romita’s run of The Amazing Spider-Man where the sole black supporting characters Joe Robertson and his son Randy interact with each other in ways which feel honest and timeless.

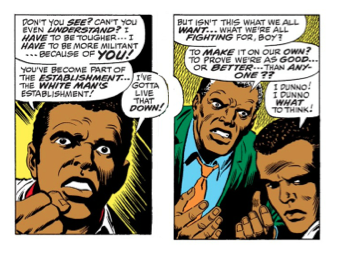

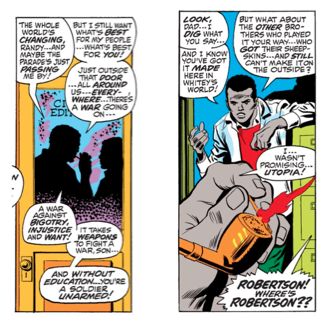

In Amazing Spider-Man issues #68-#70, Randy gets involved with campus protesters who want the school Exhibition Hall to be used as a low-rent dorm for students. It leads into a number of scenes where Joe and Randy try to convince each other what’s right for a black man to do in the modern world of 1969. Quotes from Robbie like “A protest is one thing! But, the damage you caused..!” resonate sharply with the critics of the Ferguson protestors. The same goes for Randy’s comments about militarism, which mirror protestor Barry Perkins comments about feeling triumphant while fighting back against the police during the Ferguson protests.

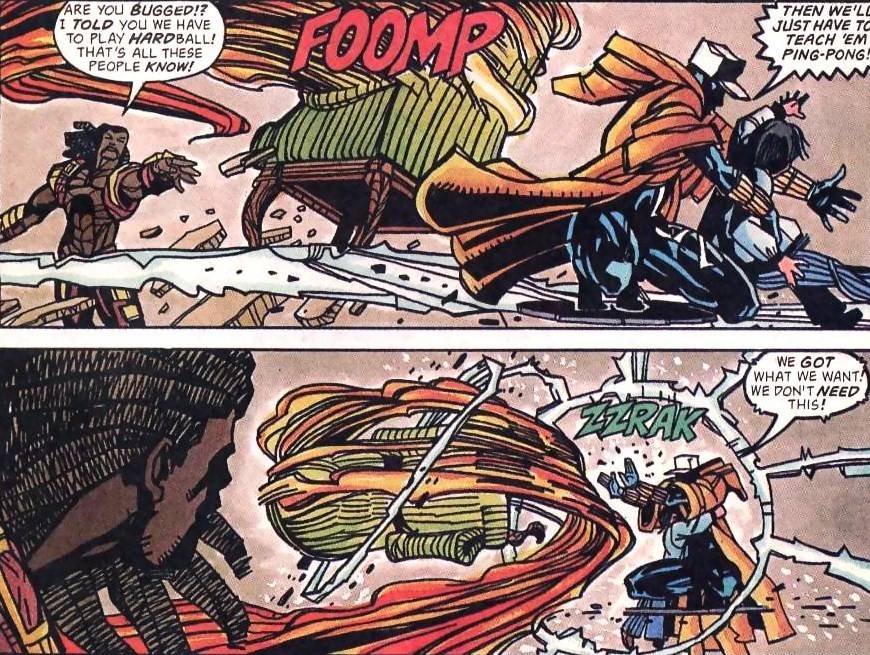

A few issues on, in #73, the creators include a scene in which Joe and Randy discuss college. Randy protests his social placement, exclaiming “What’s the point bein’ a success in Whitey’s World? Why must we play by his rules?” Joe (or Robbie as he’s often called) maintains that by only educating one’s self can one truly bring about societal change. Randy, looking out at the reader, asks his father to explain why, if that’s true, educated black men in America haven’t prospered. Robbie has no response — he’s interrupted by J. Jonah Jameson bursting into the room ranting about Spider-Man. As in Static #4, where Holocaust’s grievances with racial inequality evaporate the minute he tries to kill a white child in cold blood, the discussion on racial inequity is silenced when the white guy (and, thematically, the white hero) enter the room.

But whatever it’s limitations, the fact remains that the two black characters in this comic are having a realistic discussion about racial injustice and how to deal with it. Randy isn’t presented as a hothead who doesn’t know any better (there was another character named Josh for that during the Campus protest arc), and Joe isn’t shown as a stodgy relic of the old guard. Education is said to be key to enlightenment, but Randy questions the very system providing the education. The scene is interrupted by a white man, but it has no easy answers for a white audience.

But the Robertsons aren’t super heroes.

So what’s the point? If black super heroes can’t engage in this type of discussion in any meaningful way, what does it matter that black supporting characters do?

If the super hero genre has been inherently, historically white, it’s all the more important to note those moments when white creators and black creators attempt to relay the black experience. It’s also important to note where they go wrong and to examine how, despite their efforts, superheroes continue to present a narrative of whiteness. The few successes can perhaps serve as a template for the future, so we don’t have another All-New Captain America to suffer through. Those few scene with Joe and Randy suggest that meaningful diversity is possible in a superhero comic, however unattainable the whole of the genre appears to make it.