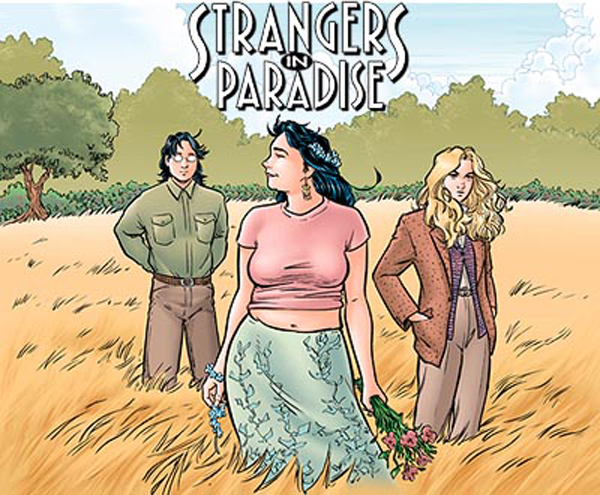

Terry Moore’s Strangers in Paradise was one of the first “alternative” comics I read when I was a teenager getting tired of Marvel (I bought it after reading the preview in Cerebus). I picked up around the middle of “I Dream of You,” I think, so fairly early in the run. I followed the series faithfully all through high school, painted Katchoo on my graduation mortarboard (and got the photo published in the lettercol!), angsted and argued over the characters, and decided with my best friend that she was Katchoo (but taller) and I was Francine (but gayer).

In short, it was the perfect graphic addiction for the kind of teenage girl I was. Later, I grew up, started hanging out with comic snobs (you know, the kind of horrible people who write for The Comics Journal), and found out my SiP love was stupid and misguided and didn’t I know Moore stole everything he knew from Jaime Hernandez?

I have to confess, I never read any bros Hernandez until last year or so, when another comics snob (allright, so I’ll name-drop) lent me the whole run of those giant Love and Rockets phonebooks, two by two, over the space of a year. The comic snobs may have a point with the ripoff thing. Hopey is Katchoo but moreso, and Francine has Maggie’s daffiness, voluption, and super-heterosexuality-with-one-teeny-exception. Both storylines could be called an exercise in fanny, in that they’re well-realized women in a women’s world, created for straight male gratification (at least the creators themselves are clearly getting off on drawing so many and varied hot women). And no one could dispute that Hernandez has it all over Moore in terms of artwork.

But I don’t really know that Moore is just a poor man’s, or middlebrow girl’s, Hernandez. If I had to pin it down, I would say Locas (if that’s the term for the Jaime parts of L&R) is better fanny, but SiP is better chick-lit.

One of the notable things about SiP is that it always had a very large female following, and those women, going by the lettercols and my own experiences, were disproportionately the type who “didn’t read comics” except of course Archie when they were little. Even today, SiP will always be one of the first works mentioned in message board threads of “what comics can I get my girlfriend into?” (of course, responders almost never follow up with “what kind of books does she like to read?” as if women were, you know, individuals, with divergent tastes. But I digress.)

I’m too lazy to google, but I don’t recall that L&R comes up in those threads more often than most popular comics do (because anyone who knows a woman who’s liked a comic, or is a woman who’s liked a comic, will mention that comic, and the list inevitably and logically ends up all over the map). I think the height of L&R’s popularity was before my time, but by the time I was aware of it, its boosters were all Comics Journal reading types who want to educate me about Important Comics.

Now, I never would have read and loved L&R if not for those people, and I am a sucker for anything anyone tells me is Culturally Important. But we run an iconoclastic blog here, and suburban Archie-reading housewives will always win out over comics scholars, at least until Archie moms make up the majority of our readers. So why does Moore capture that demographic better than Hernandez?

Mostly because SiP is a straight-up soap opera, whereas Locas is only an homage to soap operas (of both the telenovelistic and professional-wrestling varieties) among other things. Maggie and Hopey have a semi-fraught relationship, where Hopey expresses frustration and jealousy over Maggie’s straight crushes and Maggie is hurt when Hopey viciously puts her down as a cover for her feelings of love. But those moments are very by-the-way, and usually played for laughs rather than drama. They do fall out and get back together occasionally, but it doesn’t really seem to matter why.

SiP was, what, fifteen years of will-they-won’t-they, while Maggie and Hopey’s sex life is more do-they-don’t-they, serving the cause of male titillation rather than suspense. You don’t ache for the women’s relationship to go to the next level, cause implicitly it has, and it was no biggie…. you just kinda hope Hernandez will get around to drawing the nitty-gritty. You want Katchoo and Francine to have sex because, the way the story’s set up, it will change everything.

Most importantly, SiP is both plot-driven and episodic in exactly the way TV soap operas are. The proportions of love triangles, scheming villainesses and flawed heroines and how they will all be changed forever drives every issue. This is great for getting a devoted, strongly identifying readership. But like soap operas, it gets really boring and repetitive and forced when it becomes clear that the creator is too attached to his characters to let them go. Which is why I quit reading years before, apparently, Francine and Katchoo Did It (and my sister insists that in her universe, SiP ended after “I Dream of You”).

Locas is a weaker soap opera, but ultimately a much more satisfying work to read straight through, because Hernandez doesn’t seem very invested in What Happens Next. He likes the locas, he likes their friends and surroundings, and he likes writing stories about them in all sorts of genres. He creates plot arcs, but he’ll nonchalantly scrap them (Maggie loves Rand Race, Hopey has a baby, etc.) when he gets bored of them, and may or may not revisit the continuity years later (note, of course, that I read all of the phonebooks of Locas together, one time, rather then following each issue over ten years like SiP, and this colours my readings). Background figures become stars and then fade out again, settings and tone drastically change around the characters.

On a superficial reading, it seems like Hernandez is just exploring whatever interests him, but what interests him ends up being more interesting than will-they-won’t-they, will-this-change-everything-forever. On the downside, the sheer virtuosity of Locas, and the people who recommended it to you in the first place, can give you the impression that there must be something else going on, something symbolic, or Literary. Maybe you’re supposed to be Learning Something from the characters, rather than lusting after them.

What a drag, man. Bring on the busty bisexuals in denial.

(disclaimer: i’m all strung out trying to finish drawing an issue, so please forgive all the hysterical italicizing and the Portentous Caps.)