A version of this essay appeared in The Chicago Reader. This is part of a weeklong Metal Apocalypse.

________________

To most civilian bystanders, there could hardly be two less simpatico white pop genres than metal and folk. On the one hand you’ve got fascist Vikings grunting gutterally about blood, Satan, and Leatherface; on the other you’ve got tree-smooching hippies warbling about peace, love, and gently blissed-out mammals. Short of some scene of hideous pillage, it’s pretty difficult to imagine any intercourse between them. “Welcome, corpse-painted stranger! A flower for your gard….eeeeearrrrgh!”

To most civilian bystanders, there could hardly be two less simpatico white pop genres than metal and folk. On the one hand you’ve got fascist Vikings grunting gutterally about blood, Satan, and Leatherface; on the other you’ve got tree-smooching hippies warbling about peace, love, and gently blissed-out mammals. Short of some scene of hideous pillage, it’s pretty difficult to imagine any intercourse between them. “Welcome, corpse-painted stranger! A flower for your gard….eeeeearrrrgh!”

And yet, intercourse there has always been. Led Zeppelin was as much a folk band as a metal one, and that tradition is carried on by horror-movie-at-the-Renaissance-Faire outfits like folk metal band Finntroll. Genre designations are, of course, notoriously slipshod, and it’s true that a joke horror outfit like, say, Venom doesn’t have a whole lot to do with the earnest protest music of, say, Pete Seeger. But if by folk you mean acoustic music with medieval English roots, and if by metal you mean thrash, death, doom, and especially black, then there’s a lot of common ground. It’s no accident that Forest is the name of both a black metal band and a 60s British folk outfit, for about both thundering metal orcs and tinkling elvish folk lingers the spirit of Tolkein and the distinctive scent of weed. If folk and metal are opposites, it’s not because they have nothing to do with each other, but because they’re mirror images — different takes on the same pagan Northern-European obsessions.

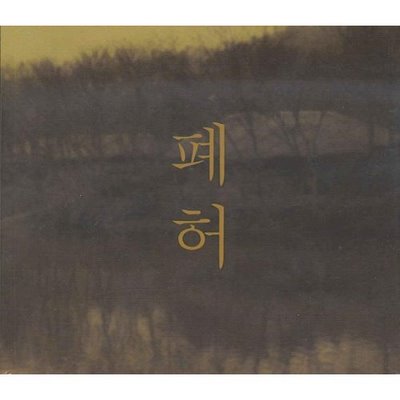

The two latest offerings on that unholy altar are the best releases of the summer: Karen Dalton’s Green Rocky Road and Pyha’s The Haunted House. Both document almost-lost recordings created in virtual isolation by eccentric quasi-legends. Dalton was an almost-famous Village folkie from the ’60s. Her musical legacy for the most part consists of ingratiating, bluesy guitar tracks in which she sings like an improbably docile Billie Holiday. This disc of recently unearthed home recordings from 1962, mostly on banjo, is the first record of a starker musical personae. Pyha is even more obscure. A native of South Korea, he recorded The Haunted House , his sole black metal opus, by himself in 2001 when he was 14 years old. Circulated on CD-R in Korea, it fell into the hands of the metal aficionados at tUMULT, who managed to track down the perpetrator. It had its official release, with extra tracks, in July.

Sonically, the two records couldn’t be more different. Rocky Road is so bare-bones it makes Alan Lomax’s field recordings sound polished. Even to call the two-track record “produced” seems a stretch. “Katie Cruel” is interrupted by a telephone ringing; part of the beginning of “Nottingham Town” is erased. Even without such cock-ups, Dalton’s voice and banjo-playing are incredibly harsh; each phrase and plunk seems to come scraping out of some abandoned hollow.

The Haunted House, on the other hand, is a dense, claustrophobic landslide of sound. The record’s signature noise is burst out static; the sound of recording technology dying in agony. Slabs of sound lurch into each other like lumbering tectonic zombies. In “Tale From The Haunted House Part 1” the background hiss and wail just…stops, to be replaced by whispering over a ghostly synthesized chorus, which in turn cuts back to giant distorted screaming and a mid-tempo drum beat that goes on and on, mindlessly repeating. Throughout the record, each of black metal’s requisite layers of sound (guitars, drums, synths, shrieks) seem manually lifted and dropped, one on the other. This sense of grinding effort reaches its peak on “Song of Oldman,” where the buzzing static actually seems to overwhelm the mics, cutting in and out in random, painful bursts, while the wailing, almost human synths distort into a horrible scraping noise, like a metal bar being dragged across your teeth.

Yet, for all their differences, Green Rocky Road’s empty space and The Haunted House’s dense maelstrom meet on the same bleak wasteland; bleached skulls calling hopelessly to each other in dry, mutually incomprehensible tongues. Given too much space or not enough, the songs and, indeed, the singers seem lost, abandoned, dead. Tempos on both albums stutter and grind down almost to paralysis. Pyha’s music is leaden enough to almost qualify as doom — on “Tale From The Haunted House Part 3” the drum machine is positively stoned, thudding down just behind the beat so the track sounds like it’s slowing down all through its 4 1/2 minute length. Dalton’s album is similarly stupefied. The banjo line on “Whoopee Ti Yi Yo” turns the familiar lyrical melody into a wavering slog, unrecognizable until Dalton’s voice comes in, off the beat and even off-key. On the endless “Nottingham Town” her picking and singing have even less to do with each other; the banjo speeds up, stretches out, trips over itself, and plunks notes so far out of tune that you’d swear the tape speed was screwy. She sounds like the Shaggs on a serious downer.

Nottingham Town” is an eerie, traditional tune with intimations of loneliness and the grave, and Dalton’s broken attack intensifies the uncanny sense of isolation and despair. In contrast, the last track of The Haunted House, “Wanderer Death March”, is not unpredictable, but insescapable. Anchored to repetitive, buzzing cymbals, increasingly strained synth washes, and throat-shredding howls, the song is a soundtrack for armageddon — a slow camera pan across clashing armies being devoured alive by mechanical insects. It, and the rest of the record, are intended as an anti-war statement, but this isn’t any kind of hopeful, or even outraged protest. Instead, it’s a vivid, bitter surrender before the crushing power of violence. Pyha seems pulverized by hate and terror; Dalton collapses in aphasia — for both, in different ways, individuality and artifice seem to disintegrate in agonizing slow-motion, falling to dust as the apocalypse approaches.

Folk and metal — and, indeed, the cold northern European culture that they epitomize — share a particular fascination with death, and, as a result, a particular take on authenticity and art. Punk tends to equate realness and sloppy incompetence; jazz, and hip hop link cred to invention and élan; blues and gospel tie it to personal emotional expression. As a celebration of the performer’s skill (or lack therof) the music is about individuality, and so about life. In folk and metal, on the other hand, the demands of the form tend to obliterate personality. In the true mountain tradition, Dalton’s singing is without affect; when she says “they call me Katie Cruel” her lack of inflection lets you know beyond a doubt that she is as heartless as she claims. Similarly, Pyha is swallowed in his own effects — snippets of taped ephemera, muffled bellowing, some poor soul gasping its last in the midst of a crackling fire — his own voice is everywhere and nowhere, neutered in its multiplicity. To be authentic is, for both, Dalton and Pyha, to be depersonalized; to be real is to be nobody. You show your commitment to the material by letting it bury you. When there is individuality, it comes across as weakness, stuttering — a falling away from the perfection of oblivion. Folk and metal are about being crushed by death — about the cold joy in self-immolation which links Protestants, and Norsemen alike.

Neither the American Dalton nor the Korean Pyha actually come from Northern Europe, of course. But their distance is, itself, part of the point. The form is as implacable as it is imperial; death doesn’t care if you’re folk, volk or other. Whether you’re cavorting with the fairies in Stonehenge, torching churches in Norway, or wandering somewhat further afield, a dirge is a dirge for everyone. Dalton’s keening and Pyha’s buzz are part of the same sexless drone, swallowing hippie and Viking alike in the abject ecstasy of annihilation.