In comics circles, Roy Lichtenstein is often condemned as a no-talent snob who condescended to comics artists even as he made millions by ripping them off. R. C. Baker in a takedown from last year, for example,not only nails Lichetenstein for his knee-jerk dismissal of his sources, but even sneers at him for his compositions, claiming that Lichtenstein’s “flabby lines, blunt colors, and graceless designs are invariably less dynamic than the workaday realism of the comic pros.” Lichtenstein took the vital, outsider pulp energy of comics and flattened it out into flaccid high-brow capitalist dreck. Rather than elevating commercial product into art, he turned art into commercial product.

This criticism, obviously, doesn’t erase the high-art/low-art binary so much as it flips it. High-good/low-bad becomes high-bad/low-good. Lichtenstein may be a transformative genius or a parasitic hack, but either way he’s defined through his relationship to something else; the thing that is not high art which he is blessing or debasing.

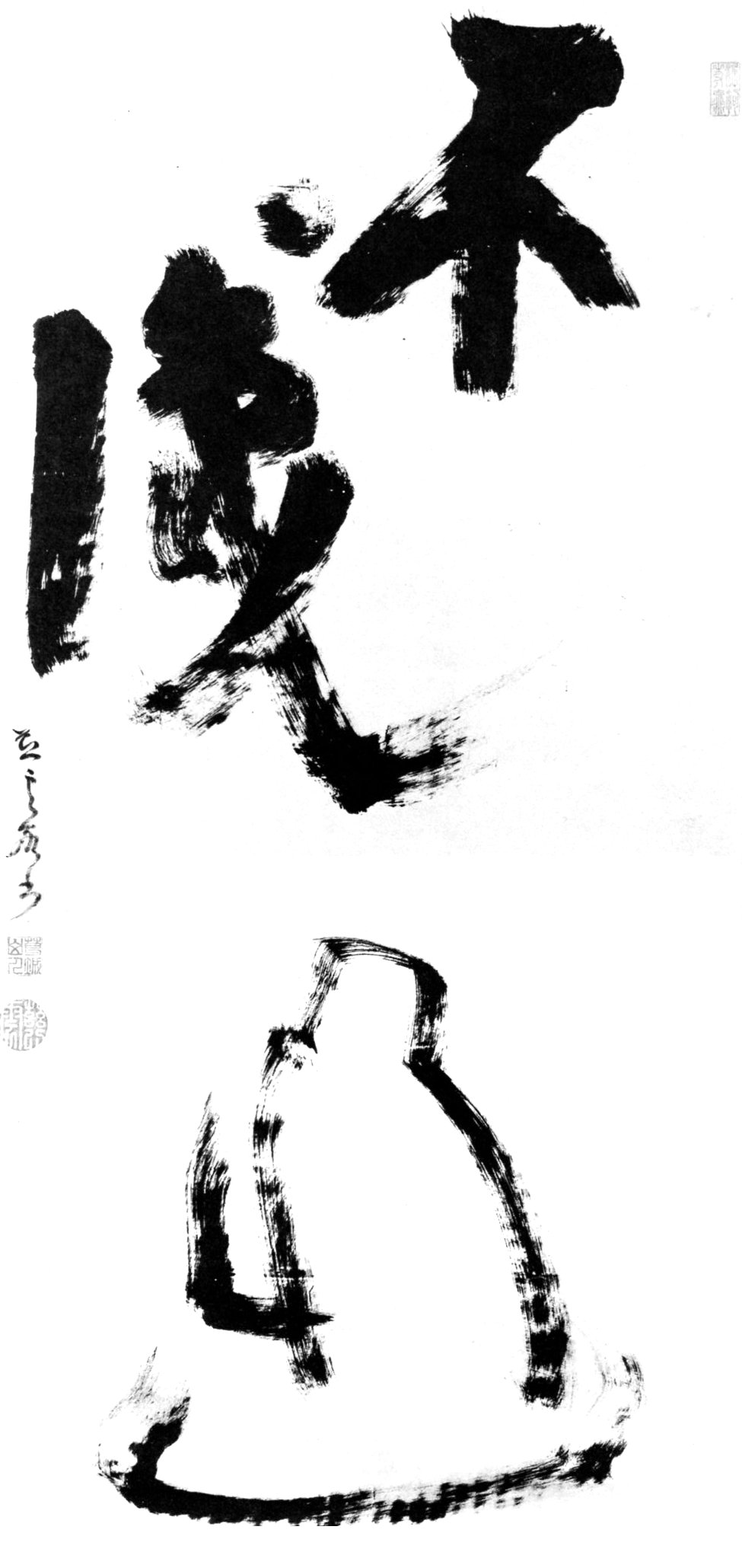

Seeing the current Lichtenstein retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago calls that narrative into question in some interesting ways. Mainly, the show makes it clear that Lichtenstein didn’t copy pulp because it was pulp. He copied pulp because he copied everything. From his early AbEx experiments which look more like half-hearted imitations of AbEX than like the real thing; to his lifetime of imitating other high art painters from Picasso to Matisse; to a series of bizarre Chinese landscape images which include, for no apparent reason, Lichtenstein’s famous imitation Ben-Day dots; to a series of drawings of his own studio in which Lichtenstein imitates his own most famous imitations — the man was a compulsive aesthetic magpie.

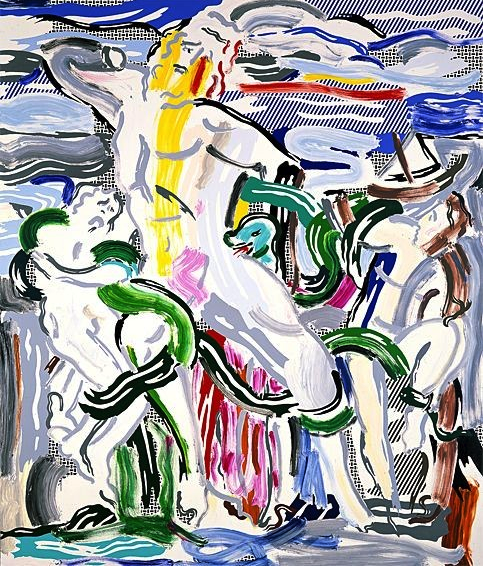

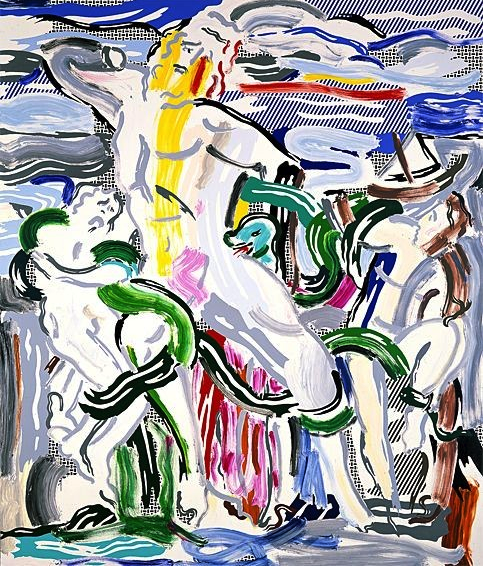

Moreover, the way he treated his non-pulp sources was in many ways similar to the ways in which he treated his pulp sources. For instance, here’s his version of the Laocoon:

I’m not sure that this really comes across in the reproduction, but in the massive original, there’s a stark contrast between the flat moire patterns Lichtenstein uses in the background and the AbExy swoops of paint that define the figures. Lichtenstein also, of course, obscures the characters’ expressions and blurs the narrative action. Some of the energy and pathos of the original are retained, but only in a deadened form. The emotion is presented as thin; a few slashes of paint against a surface that asserts itself precisely as patterned, meaningless surface.

Of course, this is what happens in Lichtenstein’s comics, too. The romance and war panels are lifted out of their narratives. The larger than life emotions end up as merely transparent, flat signs of “larger than life emotions”.

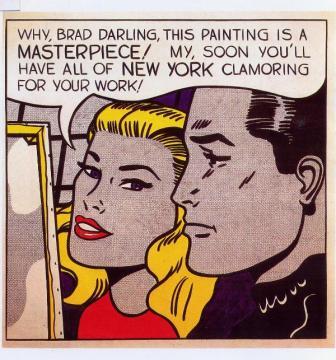

Like Laocoon, the drowning victim here is abstracted from her predicament and inflated; the energy, concentrated and expanded, collapses under its own weight. The panel is just its surface, there is no Brad outside it, and the only thing to do (for good and ill) is to sink.

I think the usual way to read this is as a playful satire of authenticity; a repetition which parodies the original and mocks its melodrama. Often this is seen as a mockery of comics or pulp in particular, but pieces like Lichtenstein’s Laocoon suggest that his target is not so limited. Rather, he seems to be sneering at sincerity and vitality itself — not at melodrama per se, but at emotion. Whether low art romance comics or high art tragedy, both point to depths, and are therefore ridiculous.

I’m sure there’s some truth to that reading…but it’s not necessarily how I see what Lichtenstein’s doing. Rather, at least for me, his work is suffused not so much with contempt as with a kind of etiolated longing. Surely there’s something almost quixotic in those Ben-Day dots; the painstaking hand-crafted effort to replicate the incidental byproduct of mass production. It’s as if Lichtenstein is trying not to ridicule the melodrama, but rather to reclaim it. the replication in this reading is not playful mockery but compulsive failure. He’s trying to frame that originary energy, and is condemned to keep trying and trying until he succeeds, which he never can.

My wife, who is a Lichtenstein skeptic, commented that he’d just had one idea, and it wasn’t all that great an idea, and he’d just kept at it with a numbing regularity. There’s definitely truth to that, and you certainly can see his inability to bottle the energy he alternately/simultaneously mocks and covets as related to his own aesthetic limitations.

You can also see it, though, as part and parcel of the historical moment Lichtenstein was in…and which we’re still in, to a large extent. Late capitalism is not an ideology that cares much about origin myths. Social authority doesn’t come from the divine right of kings, but from the repetitive images of value and community that circulate endlessly without any necessary prototype. Even the Founding Fathers are little more than a subcultural marketing trope at this stage; George Washington is just a cutesy infantilized placemat distributed for fun and profit. Which, not coincindentally, is what Lichtenstein’s version of George Washington crossing the Delaware looks like.

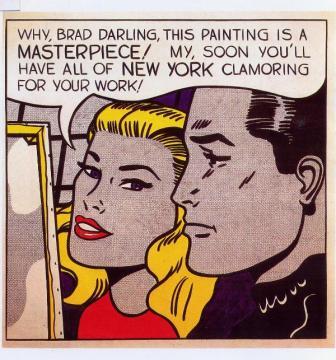

Lichtenstein is obviously a beneficiary and an exploiter of post-modernism…but he also can be seen, perhaps, as a victim of it. Imitation isn’t necessarily flattery, but it almost always has something to do with desire. When he has one of his cartoon women declare , “Why Brad, darling, this painting is a masterpiece!” it may be a sneer at pulp’s idea of high art, but it also seems like a nostalgia for that instantly recognizable work of genius, which that character, and that comic, may believe in, and so perhaps achieve — but which Lichtenstein himself can only wish for.

It’s tempting to see Brad’s sad frowny face as self-portrait; a depiction of that distance and that distress. But of course Lichtenstein is never in his paintings. At best, he’s on the surface.

___________

Folks may also want to check out Kailyn Kent’s recent discussion of Lichtenstein. Scroll down for numerous comments.