In the spirit of our Jaime roundtable, a punk rock mix. Download Hinkley Had a Vision.

1. Capybara — Shonen Knife

2. Another Genius Idea From Our Government — Erase Errata

3. Marmoset — Rapeman

4. Human Fly — The Cramps

5. Down on the Street — The Stooges

6. Tight Black Plants — The Plasmatics

7. Neanderthal Dike — Tribe 8

8. Hate Breeders — The Misfits

9. It’s Halloween — The Shaggs

10. Radio G. String — Bow Wow Wow

11. Pretty Vacant — Sex Pistols

12. New Breed — Pussy Galore

13. Hinkley Had a Vision — The Crucifucks

14. Institutionalized — Suicidal Tendencies

15. Life Sentence — Dead Kennedys

16. Screaming at a Wall — Minor Threat

17. Who Am I — D.R.I.

18. Radiation Sickness — Repulsion

19. White Riot — The Clash

20. The KKK Took My Baby Away — Ramones

21. Too Bad on Your Birthday — Joan Jett and the Blackhearts

22. Political Song for Michael Jackson to Sing — Minutemen

23. Thank You — Swans

24. Hot Topic — Le Tigre

Tag Archives: Noah

Utilitarian Review 3/24/12

On HU

In our Featured Archive post this week, Caroline Small explained why Jaime Hernandez is (unfortunately) not like a soap opera.

I reviewed albums by two punk rock girl bands: Shonen Knife and Forever.

I reviewed a book about rock and the apocalypse and argued that rock realy is the devil’s music.

Most of this week was devoted to our ongoing Jaime Hernandez roundtable. This week we had posts by Marc Sobel, Derik Badman, James Romberger, and Richard Cook. You can see an index for the whole ongoing roundtable here.

And finally Monika Bartyzel explained why Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s Xander Harris is a sexist ass.

Utilitarians Everywhere

At Splice Today, I talk about trying and failing to vote for Romney in Illinois.

Other Links

Eli Zaretsky on Obama and the limits of reason.

A nice post on Chet Baker.

On defiling Corto Maltese.

Robert Stanley Martin and Tom Spurgeon talk about Watchmen, canons, and Calvin and Hobbes here and again here. As a bonus, Tom explains in some detail why he despises HU in general and me in particular.

Punk Rock Girls

Since we’re doing a Jaime roundtable, I thought I’d break out some old punk reviews for the intermission. This Shonen Knife first appeared on Madeloud, the Forever review I think was pubished in Bitch Magazine.

___________________

Shonen Knife, Free Time

I haven’t heard any of Shonen Knife’s albums since 1998’s sublimely silly Happy Hour. Honestly, I wasn’t even aware that they were still a going concern. So when I picked up their latest, I was excited, but a little nervous as well. They’ve replaced their founding bassist, they’re a decade past their heydey — Lollipops and Fish Eyes forbid, but…is it possible that they suck now? Could their cuteness have curdled?

I needn’t have worried. Shonen Knife’s formula has stayed the same: Ramonesesque three-chord songs backing adorably dada lyrics about food, animals, or any other topic as long as it is treated as if it were a food or an animal. It’s simple, it’s unpretentious, and — even if the indie scene has moved on to other things — it works every bit as well in 2010 as it did in the 90s. The most characteristic outing here is undoubtedly “Capybara,” an insanely catchy tune about…well, you know. “South American animal/always biting grass….roly-poly body shape/swimming very well.” Sing it in a winsome female voice with a Japanese accent, shifting into a Beatles-y psych chorus to announce “Sleeping, biting, all the time/Sleeping, snoring, all the night” — it’s so comforting. In fact, the only way it could possibly be improved is with a techno version sung in Japanese — which is thoughtfully included as a bonus track.

“Comforting” pretty much defines Shonen Knife’s whole aesthetic. Greil Marcus and a million sad aging morons may point to the Clash and mumble incoherently about fighting the power, but in Japan they know that punk is music to shake your toddler to. “Rock N Roll Cake” isn’t about keeping the faith — it’s a recipe for woolgathering. (“Rock cake/ I want to sleep inside it…Roll cake/I can have funny dreams.”)

Even a song like “Economic Crisis” is not a call to arms but a cheerful ditty. And “Perfect Freedom” isn’t about the allure of Dionysiac abandon, but is instead a thoughtful, cautionary note from your mildly dotty aunt. “An…archy in the UK/it might be a mistake.”

“Love Song” though, is my absolute favorite. The band nods to girl group garage with a tune that adds some sway to the rock as they sing about how they don’t really like love songs, but everyone likes to listen to them. “Maybe I have a strange mind,” they muse, and then, in half parody, half capitulation, they start trotting out the clichés. “I want you, ooooo/ I need you, oooo/ such phrases/embarrass me.” The completely disarming sincerity of the distanced disavowal sung in those little girl voices just about breaks my heart. There are another six albums that Shonen Knife released over the last 12 years, and I’m thinking I’m going to have to go back and get them all.

_______________

Forever, Forever

According to their press materials, Forever was conceived in a van. While travelling as part of Me and My Arrow, Shenna Corbridge (vocals), Jen Nigg (bass and vocals), and Joel Lopez (drums) got the opportunity to go on another tour instantly. Their bass player didn’t want to…so the remaining three just picked up a fourth (guitarist Jael Navas), formed a new band and went anyway.

Forever certainly sounds like it’s the brainchild of a bunch of folks who want the road to go on…well, forever. The music is enthusiastic, unpretentious, professional pop-punk that hits all the genre expectations — fast (but not too fast) tempos; catchy, familiar hooks; raw (but not too raw) production; vocals with a tinge (though just a tinge) of cowpunk swing.

Live, I bet they’re fabulous; enthusiastic, as happy to play in front of 2 people as in front of 300, in love with the true-believers thrashing away in the audience. On record, though, it’s hard to see the point. Not that there’s anything wrong with Forever, just as there was nothing wrong with the first million bands that sounded exactly like them. The only real variation on the 15-minute record is “Who’s Haunting Me?” which picks up speed enough to verge on hardcore. It’s hardly earth-shattering, but when you’ve been in the van this long, any change in scenery is worth pointing out.

Listen To If: You’re a Very, Very Old Punk or a Very, Very New One

Listen To While: Jogging Short Distances

Utilitarian Review 3/17/12

On HU

Our featured archive post this week was Franklin Einspruch’s illustrated version of Wallace Steve’s poem “Of Mere Being.

Albert Stabler on the metal vs. punk, Arriver’s Tsushima, and Russian military disasters.

Nate Atkinson on how he kept Moebius in his living room.

Matthias Wivel on death in Moebius’ last works.

And we finished the week up with the beginning of our Jaime Hernandez Roundtable. Deb Aoki talked about her experience as a Jaime-loving punk rocker in Hawaii; I talked about nostalgia in Jaime’s work; and Jones, One of the Jones Boys explained how you should like Jaime because he said so. The index to all post is here.

The roundtable will continue through all of next week with contributions by regular Utilitarians and guests.

Utilitarians Everywhere

At the Atlantic, I reviewed Nicholas Cage’s dreadful new movie Seeking Justice, and talked about revenge narratives.

At Splice I sneered at Rush Limbaugh and Bill Maher.

Other Links

Matthias Wivel on the Hermetic Garage.

If you buy Before Watchmen, Alan Moore hates you, God bless him.

Ken Parille on why male supeheroes don’t show any skin.

Smart Bitches make fun of the nipples in romance novels.

When You And I Were Young, Maggie

Jaime Hernandez’s “Browntown” has been lauded by everyone from Tom Spurgeon to Jeet Heer, the later of whom states that it is “arguably one of the best comics stories ever”.

It’s a bit of a let-down, then, to actually read the thing and discover a decent but by no means revelatory, piece of program fiction. All the hallmarks are there: the precocious child narrator as guarantor of authenticity; the ethnic milieu as guarantor of authenticity; the sordidness as guarantor of authenticity and the trauma as guarantor of authenticity. Poignant ironies fall upon the narrative with a sodden regularity, till the only landscape that can be seen is the wet, heavy drifts of meaning.

For what it is, “Browntown” isn’t terrible. Jaime’s precocious child narrator is endearing

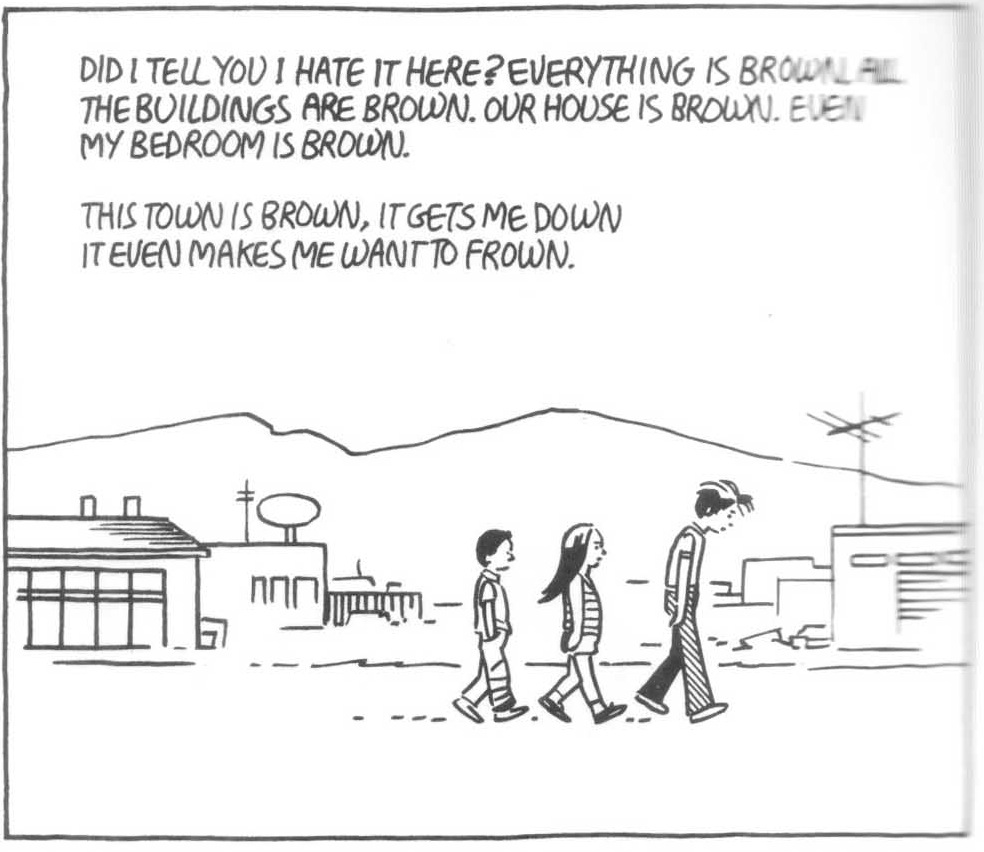

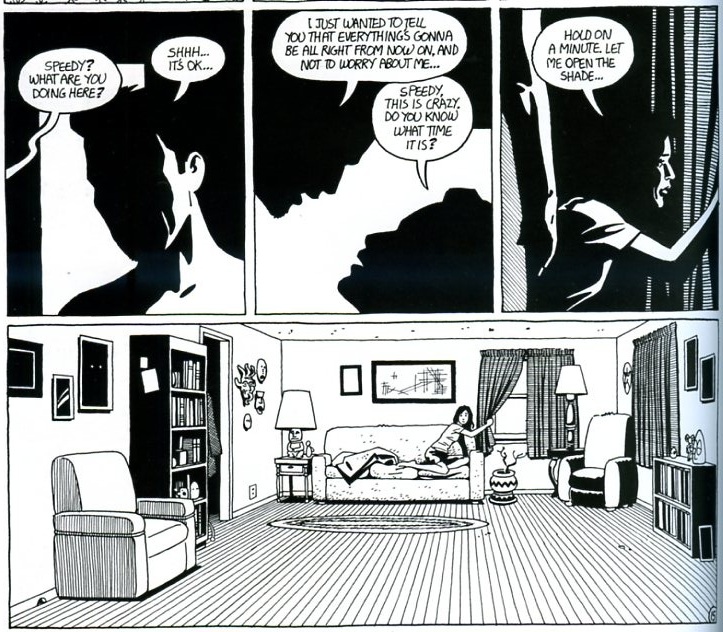

his ethnic milieu is surprisingly uninsistent and unforced; his traumas are doled out with a disarming lightness — as when Calvin’s years of abuse are limned in the space between panels:

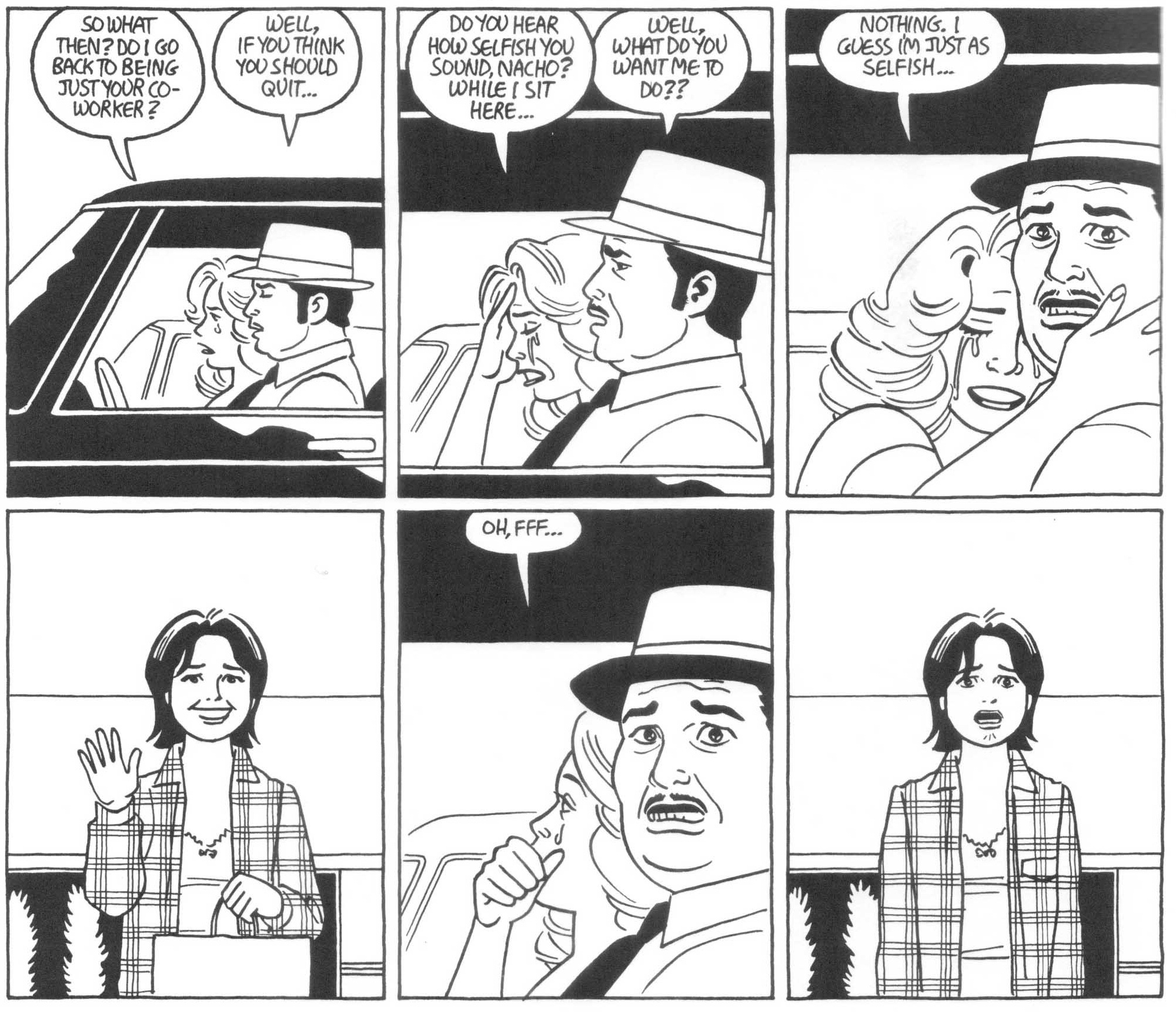

But still; there’s nothing particularly brilliant here, either in the use of language, or in the drawing, or in the use of the comics medium. In this sequence, for example, Jaime uses a series of verbal and visual clichés to present the end of an affair.

“Nothing, I guess I’m just selfish,” she says, as the stylized tears pour down. The camera moves closer, and then we’ve got a shot/reverse/shot. Entirely competent story-telling, sure. Masterpiece by one of the genre’s greatest creators? For goodness’ sake, why?

_________________________________________________

I read a fair bit of the Locas stories for this post — Death of Speedy, The Education of Hopey Glass, The Love Bunglers, bits and pieces of other stories, including Wig Wam Bam. I haven’t exactly grown more fond of Jaime’s work, but I think I have a better sense of what I’m supposed to like about it.

Which would be nostalgia. The difference between “Browntown” and an anonymous short story in a lit magazine isn’t Jaime’s skill, or his handling of plot or theme or character — none of which, as far as I can tell, rise above the pedestrian. Rather, “Browntown” is different not because of what’s in it, but because of what’s outside it: the years and years of investment in the characters, by both the author and his readers. Here, for example:

You see Maggie from a distance, and then in close up. It’s not an especially interesting or involving visual sequence…except that this is the first time in the story that Maggie appears as an adolescent, thirteen years old and post-puberty. For those who have followed Jaime’s work (or even just read the first installment of the Love Bunglers that precedes this piece in Love and Rockets 3), that face is finally, recognizably, the Maggie we know (or one of the Maggies we know). As a result, there’s a charge there of recognition and delight. It’s analogous, perhaps, to Lacan’s description of the mirror stage:

This event can take place… from the age of six months, and its repetition has often made me reflect upon the startling spectacle of the infant in front of the mirror. Unable as yet to walk, or even to stand up, and held tightly as he is by some support, human or artificial…he nevertheless overcomes, in a flutter of jubilant activity, the obstructions of his support and, fixing his attitude in a slightly leaning-forward position, in order to hold it in his gaze, brings back an instantaneous aspect of the image….

We have only to understand the mirror stage as an identification , in the full sense that analysis gives to the term: namely, the transformation that takes place in the subject when he assumes an image – whose predestination to this phase-effect is sufficiently indicated by the use, in analytic theory, of the ancient term imago.

This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child at the infans stage, still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence, would seem to exhibit in an exemplary situation the symbolic matrix in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form, before it is objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other, and before language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject.

As always, Lacan is a fair piece from being comprehensible here…but in general outline, the point is that the child sees its image in the mirror — an image which is whole and coherent. The child identifies itself with this image, and so jubilantly experiences, or sees itself, as coherent and whole.

In her book Reading Lacan, Jane Gallop points out that the jubilation and excitement of the mirror stage is based upon temporal dislocation:

…in the mirror stage, the infant who has not yet mastered the upright posture and who is supported by either another person or some prosthetic device will, upon seeing herself in the mirror, “jubilantly assume” the upright position. She thus finds in the mirror image “already there,” a mastery that she will actually learn only later. The jubilation, the enthusiasm, is tied to the temporal dialectic by which she appears already to be what she will only later become.

Thus, there is a rush of pleasure in seeing the woman Maggie in the adolescent Maggie; the future image charges the past.

But the mirror stage is not just about recognizing the future in the present. It’s also about creating the past. Gallop explains that before the mirror stage, the self is incoherent; an unintegrated blob of body parts and non-specific polymorphous pleasures. But, Gallop continues, this is an illusion; the self cannot be an unintegrated blob before the mirror stage, because it is the mirror stage that creates the self. Thus:

The mirror stage would seem to come after “the body in bits and pieces” and organize them into unified image. But actually, that violently unorganized image only comes after the mirror stage so as to represent what came before.

The mirror stage, then, provides an image not just of the future, but of the past. The subject “assumes an image” not just of what she will be, but of what she was; the coherent image of the self is not just an aspiration, but a history. When Lacan says:

This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child at the infans stage, still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence, would seem to exhibit in an exemplary situation the symbolic matrix in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form…

the specular image that is assumed is precisely the infans stage, and the I that is precipitated is precisely the primordial form. The jubilation is not just in seeing a future coherent self, but in seeing a past self that is coherent with both the present and future.

Or to put it another way, the attraction of nostalgia is not the idealization of the past, but simply the idea of the past — and of the future. It’s the romance of self-identity. Hence, nostalgia in the Locas stories isn’t a function of actual time (a reader who has in truth read for decades) so much as it is a projection of imagined history. How many times has Jaime drawn Maggie (or Perla, or Margaret, or…)? All of those images are a part of a self, snapshots of a connected chain of bodies linked from infancy to middle-age to (presumably) death. As Frank Santoro says in his piece about the Love Bunglers:

Something extraordinary happened when I read his stories in the new issue of Love and Rockets: New Stories no. 4. What happened was that I recalled the memory of reading “Death of Speedy” – when it was first published in 1988 – when I read the new issue now in 2011. Jaime directly references the story (with only two panels) in a beautiful two page spread in the new issue. So what happened was twenty three years of my own life folded together into one moment. Twenty three years in the life of Maggie and Ray folded together. The memory loop short circuited me. I put the book down and wept.

The power of the Locas stories, what makes them special, is not any one story, or instant, or image, but the knowledge of the whole — not in the sense that each part contributes to a greater thematic unity, but in the sense that simply knowing there’s a whole is itself a delight. You can read the Locas stories and know Maggie, not as you know a friend but as an infant knows that image in the mirror — as aspiration, as self, as miracle.

_______________________

And, of course, as illusion. The reflection in the mirror, the coherent past and present I, is a misrecognition — it’s not a true self. Jaime’s use of Maggie as nostalgic trope, then, functions as a deceptive, perpetuated childishness; a naïve acceptance of the image as the real. Consider Tom Spurgeon’s take on “The Death of Speedy”:

Hernandez’s evocation of that fragile period between school and adulthood, that extended moment where every single lustful entanglement, unwise friendship, afternoon spent drinking outside, nighttime spent cruising are acts of life-affirming rebellion, is as lovely and generous and kind as anything ever depicted in the comics form.

That could almost be a description of “American Graffitti”, another much-lauded right-of-passage cultural artifact noted for its compelling, yearning encapsulation of time. I would agree that this is a major characteristic of Jaime’s work…but whereas for Tom that’s the reason Jaime’s a favorite creator, for me it’s the reason that he isn’t. Hopey’s nightmare hippie girl schtick; the shapeless but coincidence-laden narratives; the sex, the violence, the rock and roll — it all seems at times to blur into that single repeated punk rock mantra, “That was so real, man. That was so real, man. That was….”

But while I don’t necessarily need to read any more of Jaime’s work ever, I do think that there are times when the nostalgia in his stories becomes not just a symptom but a theme. For example, looking again at that image of the suddenly post-pubescent Maggie from “Browntown”.

As I said, this is a moment of recognition. But whose recognition? The panel is from the perspective of Calvin, who is both Maggie’s little brother and the sexual victim of the boy Maggie is talking up. While readers see suddenly the grown-up Maggie they know and love, Calvin is seeing, perhaps for the first time, a grown-up Maggie who he does not know, and who he fears and resents as a potential sexual rival. The reader’s image of Maggie — the shock of her newfound adulthood — lets us see her, to some extent, as Calvin sees her (and, indeed, allows Jaime to subtly tell us how Calvin sees her). At the same time, looking through Calvin’s eyes inflects and darkens Maggie’s new adulthood; the overlapping perspectives capture not just the excitement of growing up, but its dangers and sadness as well. The mirror image is also a primal scene, the discovery of self also a loss of innocence. What Gallop says of Lacan might also be said of Jaime:

When Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge, they anticipate mastery. But what they actually gain is a horrified recognition of their nakeness. This resembles the movement by which the infant, having assumed by anticipation a totalized, mastered body, then retroactively perceives his inadequacy (his “nakedness”). Lacan [or Jaime?] has written another version of the tragedy of Adam and Eve.

Another example of the way nostalgia is thematized is in the ghost scenes in “The Death of Speedy.”

On the one hand, this, like the entirety of the derivative “West-Side Story” plot, is fairly standard issue melodrama. But in the context of Jaime’s oeuvre, there’s something (eerily?) fitting about Speedy’s disappearance into a darkened silhouette, a kind of icon of himself. Speedy’s a projection, a specter given meaning only by his past. But that’s not just true for Speedy — it’s true for everyone in the Locas stories, who appear and then disappear and then reappear further up or down the timeline. A ghost is a kind of distillation of nostalgia, a memory that walks. At moments like this in Jaime’s work, the compulsive authenticity claims become almost transparent, as everyone and everything turns into its own after-image. We cannot see the present without seeing the past and the future, which means that we don’t ever see anything but an illusion, an image of coherence.

This is perhaps one way to read the conclusion of The Love Bunglers. Many people have read it as a happy ending for Maggie and Ray; the final triumph of romance after many trials. Thus, Dan Nadel:

In the end we flash forward some unspecified amount of years: Ray survives and he and Maggie are in love and Jaime signs the last panel with a heart.

And maybe Dan’s right. But it’s also certainly the case that that ending is only reflection; it’s what we want to see in the mirror.

Two Maggies side-by-side look in two mirrors at two Maggies. We see doubles doubled, the Maggies we love seeing the Maggies we love. This is the way cartooning works; one image calls forth another and another, the characters become themselves through sequence and repetition. As Dan Nadel says, “It just works. They’re real.”

But at the same time as it solidifies Maggie, the doubling of the mirror stage also disincorporates her. The second Maggie in the mirror…doesn’t she look younger than the first? Is time passing, or is the mirror image just an image — the future Maggie that present Maggie needs to see in order to make the past Maggie cohere? If the happy-ending Maggie looking in the mirror is just a dream to retroactively solidify the grieving Maggie, perhaps the grieving Maggie looking in the mirror is herself a dream, an image to confirm the tragedy. And so it goes; Calvin’s unlikely assault is an image there to give weight and shape to his childhood trauma; Maggie kisses Viv and is rejected by her to give weight and shape to their past — or and simultaneously the past gives weight to the future, and on and on, image on image, through the never-ending jubilant shocks of misrecognition.

__________________

Jaime’s oeuvre, I think, can be seen as a mirrored engine; turn the crank and nostalgia is infinitely reflected. It’s an impressive delivery system. As with the Siegel/Shuster Superman, or the Twilight books, I can see the appeal, even if, for me, there’s something more than a little off-putting about the efficiency of the mechanism.

__________

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.

Utilitarian Review 3/10/12

On HU

For our Featured Archive Post, Vom Marlowe looked at Billy and Blaze.

Erica Friedman discussed the Defenders and other comics she likes despite themselves.

I talked about empowerment and dicks in Almodovar’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!

Ng Suat Tong on the not so transgendered world of Tezuka’s Princess Knight.

Domingos Isabelinho on Tim Gaze and abstract comics.

Kinukitty on angst and cat reaction shots in the yaoi manga I Give to You.

I did a series of reviews through the week on Pop R&B. Beyonce, Ashanti, Mariah, Britney, and more.

Utilitarians Everywhere

At the Atlantic I review Gail Carson Levine’s children’s book of William Carlos Williams adaptations and talk about how contemporary poetry has isolated itself. Plus! A poem by me!

At Splice Today I talk about Andrew Breitbart and new media navel gazing.

Also at Splice I review the crappy new Springsteen album.

Other Links

A nice essay on Habibi and Orientalism.

A comics anthology supporting marriage equality is running a kickstarter campaign.

Qiana Whitted on how where you shelve comics affects how you read them.

Radio Pop That Didn’t

These reviews originally ran on Madeloud.

________

Brooke Valentine

Physical Education Mix Tape

Houston native Brooke Valentine’s debut, Chain Letter, was one of the greatest R&B albums of the oughts…or of all time, for that matter. From the loping, burping strut of “Pass Us By,” to the tongue-in-cheek goth-funk of “I Want You Dead” to the aching, breathy heartbreak of “Laugh Til I Cry,” Chain Letter was all over the place stylistically, but tied together with humor, smarts, and audacity. Valentine and mad genius producer Deja were convinced down to the giant flying bat on Brooke’s half-shirt that female-helmed R&B could be every bit as bizarre and crazy as rap by the likes of Outkast and Ol’ Dirty Bastard, and they were damned well going to prove it.

Musically they succeeded, and then some. Commercially…well, that’s a different story. Chain Letter had only one bona-fide hit, the funny but relatively unadventurous Lil’ Jon produced “Girlfight.” Singles released to promote her follow-up went nowhere, and after months of hemming and hawing by her distributor, Virgin, the album was shelved and she limped back to Deja’s Subliminal label.

Earlier this year, Physical Education, the album that never was, was finally released by Subliminal as a mixtape. It’s definitely a retrenchment. The flashes of bizarre wit and eclecticism are gone; there aren’t even any ballads here, much less profanity-laced tirades against valley girls. Instead, what we’ve got is track after track of deep, throbbing, ominous Houston crunk.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Valentine and Deja may be working to keep the smarts on the down-low, but try as they will, they can’t quite make a duff track. Valentine is not by any means a great singer, but throughout the album her throaty whispers and moans drip sex and insouciance. The production (I presume by Deja, though there were rumors that Valentine did some of it herself) is also stellar. Pimped Out is built around a weird synth motif that sounds almost like an electronic duck has been drafted to quack rhythmically while Chamillionaire raps along. “Make It Drop” has some of the funniest rear-obsessed lyrics this side of Sir Mixalot: “I can make that ass pop/like hydraulics on drop; I can make that ass stop/like you runnin’ from the cops.” “Gold Diggin’” starts with a wash of demi-classical synth strings and then opens out into a heavy, hesitating thump which also somehow manages to swing hard enough to lift Valentine and the uncredited guest rapper up off the backing like they’re jazz performers. “Thug Passion,” too has an impossibly hooky stuttery beat which keeps you off-balance no matter how many times it repeats.

The only thing I miss here is the 2006 “D-Girl” single, with its surging keyboards and that sample from N.W.A. pattering through the tough production like a whispered, half-forgotten threat. Even with that track left off, though, this is still hands down my favorite R&B release of 2009 to date. So if you’re going to download it, be sure to pay for it, would you? I don’t want Valentine and Deja to completely run out of money before they release their next full length.

___________

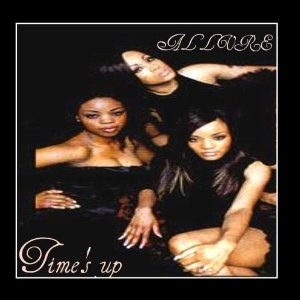

Allure

Patiently Waiting; Time’s Up (4 stars)

Like everyone else, the vocal group Allure was pulled along in the wake of Destiny’s Child in the early 2000s, abandoning the smooth jams of the 90s for a tighter, funkier, more hip-hop friendly sound. But where Beyoncé has moved on, Allure got stuck. Their new ep (Patiently Waiting) and album (Time’s Up) both sound like they’ve dropped through a wormhole from 2001.

Which is kind of great. Nothing against today’s radio, but there was really something special about that moment a decade or so ago when R&B songwriting and production suddenly caught on fire — a mixture of newbie fumbling and professional calculation as hip hop realized that this, this right here was the way it was going to take over the world. No doubt there’ll be an uncomfortable retro-early-oughts movement any time now, but this isn’t that. Instead, Allure clearly just never got the memo that itchy/cheesy Kevin Briggs beats aren’t where the market is at.

Patiently Waiting takes that obliviousness and runs with it. From the sweeping, harmonized tough-girl-threats-with-horn-sample of “What Goes Around;” to the materialist tinny looped steel-drum reworking of “Favorite Things;” to “Treat Him Rite” with overdriven eighties video game bleeps that somehow slide right into a sexy, laid-back groove — it’s 20 perfect minutes of gloriously out-of-date pop. Hell, even the obligatory skit is great, featuring some of the most piercing shrieks I’ve ever heard outside of a Diamanda Galas album.

Twice as long, Time’s Up has a bit more filler, but it’s still plenty good. “The Other Side” is awesome faux early Timbaland, with layers of beats and squeaky vocal hiccups bounding around each other while the singers volley “you’re a no good cheater” lines back and forth between the soloist and the harmony backup. “With Out U” is a great mid-tempo disco roll — Andy Gibb for the hip hop generation. “Walk in My Shoes” is something of a rote ballad with too, too gospel vocals — but even so, the low-key guitar playing and the harmonizing makes it listenable.

It’s those harmonies that are maybe the most refreshing thing about the album. Not to take anything away from the amazing sucrose delivery system that is Danity Kane, but there’s also really something to be said for a group whose vocal arrangements are tight enough to add hooks to the song, rather than just keeping up with the production.

Even Beyonce herself has given up on the vocal group aspects of her legacy these days, so it’s up to groups like Allure and the similarly-backward-looking Cherish to keep the faith. Not a good career move, exactly — harking back a decade is no way to get radio play. In fact, both Patiently Waiting and Time’s Up are CD-Rs, burned on demand, which suggests the singers themselves don’t expect to move a ton of copies. But whether or not anyone buys it, this is still some of my favorite music of the year — even if it is the wrong one.