In comments to his post on Tsuge, Tom Gill has a lengthy discussion of Tsuge’s relationship to the zen concept of evaporation. I thought I’d reprint it below.

Dear Domingos,

You ask: Do you think that the fish going away is a symbol of what Tsuge calls “evaporation”?

The short answer to your question is “yes indeed.” Evaporation, or jôhatsu in Japanese, is an important cultural trope in Japan. Certainly it relates to the Zen Buddhist idealization of “nothingness” (mu), which is discussed at some length in the interview you cite (originally in Japanese, translated into French). To disappear, to become nothing: that is the dream of Zen thinkers. In Tsuge’s works, (1) death, (2) escape, (3) enlightenment, (4) laziness/irresponsibility, are intertwined concepts. To evaporate is to die, to escape from responsibility, to disappear to a perhaps more enlightened elsewhere. As well as the philosophical/religious aspect of this metaphor there is also a political/sociological one. Tsuge’s semi-autobiographical heroes reject the materialism of mainstream society, or simply cannot relate to it. To be lazy, to refuse/fail to conform to the socially sanctioned image of the “salaryman” is a kind of statement, aligning one with a romantic, escapist, world-renouncing strand in Japanese culture. I discuss it as a masculine fantasy in a paper I published a few years ago: When Pillars Evaporate: Structuring Masculinity on the Japanese Margins.

Here I oppose the concept of evaporation/jôhatsu to that of the great pillar, or daikoku-bashira, which means both the central pillar supporting a house and a man who is the economic supporter of the household. I stumbled upon this theme while studying Japanese day labourers, the topic of my 2001 book from SUNY Press, Men of Uncertainty. This is why I am interested in Tsuge: he is a kind of hero of the jôhatsu side of Japanese culture. His comics, and also his essays, would no doubt appeal to the more thoughtful day labourer. It may be a translator’s little joke, but the prize-winning memoir of a day labourer, San’ya Gakeppuchi Nikki (A Diary of Life on the Brink in San’ya [a slum district of Tokyo]) was rendered into English as A Man with No Talents – essentially the same title as Tsuge’s book-length manga Munô na Hito, translated into French as L’Homme sans talent. The author of that book is totally anonymous, using the pseudonym Ôyama Shiro, and shuns publicity as Tsuge does.

What I am trying to say is that though Tsuge Yoshiharu is a unique artist/autor, he did not spring out of thin air. He is rooted in a strong tradition of world-renouncing, foot-loose, romantic losers. Like Tsuge and his fictionalized protagonists, day labourers traditionally drift from town to town, stay in the cheapest possible inns, and have no clear idea of their future. The Tsuge protagonist is described as a tramp or vagabond (clochard) in the interview you cite, probably a translation of “furôsha” – day labourers are frequently described similarly. Here is a short extract from my paper, which may be relevant to this discussion. In it I discuss what happens when older day labourers give up the struggle to make a living out of manual labour and apply for welfare.

getting welfare does inevitably affect one’s personal identity. Solitary day laborers have already abandoned or rejected the image of the daikoku-bashira as a man supporting a household; once they apply for welfare, they effectively admit that they cannot even support themselves.… Thus themes of strength and weakness, independence and dependence, mobility and immobility, twine themselves around the day laborer’s career and changing identity.

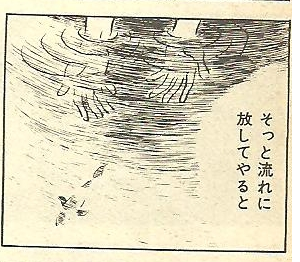

Protean Passivity at the Margins

These ambiguities are expressed in some of the language associated with day laboring. They often describe themselves as having “drifted” (nagareru) into the doya-gai (skid-row district), a term that elegantly combines the concepts of mobility and passivity. The imagery surrounding these drifting day laborers is often liquid and piscine. They are called ‘angler-fish’ (ankô) as they wait on the seabed of society for a job to come along. They may be caught in abusive labor camps called ‘octopus traps’ (tako-beya). When a man is mugged while sleeping in the street they call the incident a ‘tuna’ (maguro), likening the victim to a tuna helpless on a sushi chef’s chopping board. Day laborers who fail to get a job say they have ‘overflowed’ from the market (abureru); if depressed they may ‘drown themselves’ (oboreru) in vice; and when troubles appear insurmountable, they may disappear overnight, or as they put it, ‘evaporate’ (jôhatsu suru).So Tsuge’s little fish comes from a strong cultural tradition in which fish and their environment are metaphors for the human condition. Consider also Tsuge’s salamander, and the floating fetus, in my previous contribution to the Hooded Utilitarian.

In the interview you cite, Tsuge describes a particularly literal and personal case of “evaporation” – when he decided to leave Tokyo, abandon his entire life, taking a train to Kyushu where he hopes to marry and settle down with a female fan of his work whom he has never met. (It is interesting to note that where male escape fantasies often include leaving one’s wife and family, for Tsuge married life is part of his post-evaporation scenario. Loneliness and desire are always in the mix for Tsuge.) He goes through numerous distractions, and actively considers marrying a couple of other women he meets on the way, but in the end he gives up and returns to Tokyo. The adventure is described in one of his essays, “Diary of an Evaporation Journey” (“Jôhatsu Tabi Nikki”), written in 1969, published in Yakô (Night Journey) magazine in 1981, and republished in his 1991 collection, Records of a Poor Man’s Travels (Hinkon Ryokôki)

He discusses it in the interview you cite, alluding to the final line, in which he states that he is now married with a kid, but feels that maybe this is his evaporated self. The implication seems to be that we cannot necessarily distinguish between the life we think we are actually living and those that we think we are merely imagining.

Anyway… yes, there is a desire expressed in the Nishibeta story to be like that little fish in the final frame, to swim away, down the river, destination unknown. Have you ever felt like doing that?

You can read all HU posts on Tsuge here.