This piece first ran on Splice Today. I’m reprinting it here as part of the Juxtaposition Blogathon at Pussy Goes Grrr.

____________________

If I were going to remake I Spit on Your Grave, the notorious 1978 rape/revenge thriller, I’d add more women. Not necessarily to the rape, but definitely to the revenge. The reason’s fairly simple: I think it would make the movie more feminist.

This is hardly at odds with the intent of the original. Director Meir Zarchi has said that he made the film after encountering a young rape victim and attempting to aid her despite police indifference. The film’s infamous 25 minute rape scene captures that sense of blunt, hopeless outrage — it has to be one of the most harrowing depictions of violence in film. Jennifer (Camille Keaton) attempts again and again to escape, only to be captured and recaptured, humiliated and brutalized until she’s little but a traumatized, naked slab of blood and terror. Meanwhile, the four rapists talk and joke among themselves, urging each other on with taunts or threats. It’s clear throughout that they’re much more interested in each other than they are in their victim. She’s just the excuse for extended male bonding and one-upmanship, a convenient non-person onto whom to safely displace and act out the real male-male passions. As Carol Clover writes in Men, Women, and Chainsaws, “the rapes are presented as almost sexless acts of cruelty that the men seem to commit more for each other’s edification than for their own physical pleasure.” Clover also notes that one of her male friends “found it such a devastating commentary on male rape fantasies and also on the way male group dynamics engender violence that he thought it should be compulsory viewing for high school boys.”

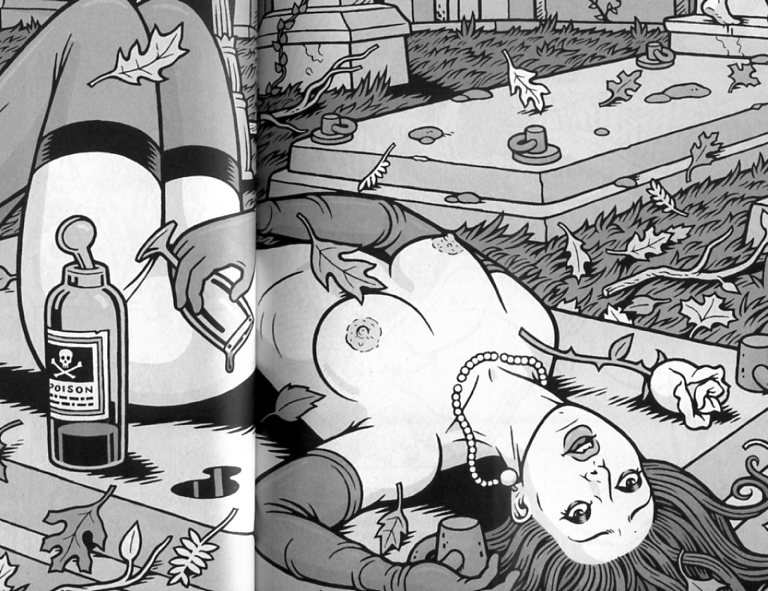

While I Spit on Your Grave is very aware of how men relate to each other, however, it has virtually nothing to say about how women interact. Its vision of female, and, indeed, feminist empowerment is entirely individual. Jennifer fights the patriarchy herself — abetted by the abject stupidity inflicted upon men by their own hierarchical obtuseness and sexism. Jennifer avoids death because the rapists deputize the mentally retarded Matthew (Richard Pace) to do the dirty work of killing her, and he wimps out. Weeks later, after she recovers, she is able to murder her assailants in large part because they are ideologically incapable of believing (a) that she is able to kill them, and (b) that she didn’t want to be raped in the first place. She seduces Matthew, fucks him, and as he cums she slips a noose around his neck and strangles him. She then finds Johnny (Eron Tabor) at the gas station, convinces him to get in a car with her by flipping her hair winsomely, and then drives him out to the middle of nowhere and forces him to take off his clothes and kneel at gunpoint. He starts to explain himself…and he’s so stubbornly obtuse that he thinks he’s swayed her, and actually allows her to seduce him again. So Jennifer takes him home with her, maneuvers him into a tub, tells him she killed Matthew (he doesn’t believe her) and then, under pretense of giving him a handjob, cuts off his dick.

Finally, she climbs aboard a motorboat with Stanley (Anthony Nichols), fools him into thinking she’s going to kiss him, then pushes him into the water and disembowels him with the motor blades. (The final rapist is the only one who doesn’t get seduced; he’s so upset at seeing his pal menaced with the motorboat that he rushes into the water, where Jennifer kills him from the boat with an ax.)

There’s obviously some satisfaction in seeing the men hoisted by their own…bits. But it’s a bitter pleasure. To get her revenge, Jennifer has to turn herself into the sexual thing the men imagine her to be. It’s notable that while the rape itself is probably about the least arousing half hour ever filmed, the seduction scenes have a queasy erotic charge. Jennifer caters to men’s desires only to cut them off, but she’s still catering. It is, then, not the men, but Jennifer who completes her degradation. The loss of her self is the price of her victory — though it’s not clear what other option she has. Men are despicable — and they are also, in this world, effectively all there is. Jennifer wins, but it’s man’s game she wins at. There isn’t any other.

Of course, feminism offers some other options — most notably sisterhood. Nor is it unheard of for rape-revenge (or rape-revenge inspired films like Tarantino’s Death Proof) to explore female relationships . So if you had to do a remake, and you wanted to throw in some clever plot twists for the jaded exploitation viewer, adding female relationships to the plot seems like it would be an unexpected but not unprecedented tack. Why not see what happens if, say, you had Johnny’s wife (who gets a notable ball-busting walk-on in the original) find Jennifer after the rape and take her side? Or perhaps more realistically, you could have Jennifer come out to the cabin with her sister, her mother — or perhaps with a girlfriend? Certainly, gay rights would have some of the polarizing power today that feminism has in the ‘70s. As such, including lesbian themes in order to ramp up both the exploitation and the political edge would be perhaps the best way to stay true to the spirit, if not the letter, of Zarchi’s original.

It probably goes without saying, but this was not the path taken by the actual 2010 remake of I Spit on Your Grave.

In fact, the remake takes the opposite approach; instead of an additional revenger, it adds an additional rapist. At one point in the remake Jennifer (Sarah Butler) maces one of her four attackers and manages to escape into the forest. She runs into the town’s sheriff (Andrew Howard), who takes her back to her cabin…where the other rapists reappear. Instead of running them in, the sheriff rather inexplicably joins them.

As I noted above, the original film took some care to show that male bonding and rivalry were central to the rape. The men’s mean-spiritedly jovial desire to “help out” sad sack Matthew by using Jennifer to deflower him; their need to impress Johnny, the way they only expressed their emotions for each other (whether affection, dislike, or envy) through aggression and humiliation — it’s those interactions which powered their misogyny and violence. And the film also took pains to show these impulses as unremarkable. In a scene before the rape, where the men chatted with each other, they didn’t appear dangerous.. Indeed, they seemed like naïve adolescents, wondering (mostly, but not entirely in jest) whether really sexy women shit or boasting about their plans to visit New York or Los Angeles. It was only in retrospect later in the film that their casual abuse of one another and their casual jibes at women appeared ominous.

The remake follows through on the group dynamics to some extent — the guys egg each other on; they bring Matthew along to lose his virginity, etc. etc. But it abandons the effort to make the men appear like just folks. Ironically, the director Steven R. Monroe gives one of his characters a video camera, and we see some of the rape through the lens. This is an obvious effort to implicate the viewer — but in fact, this version of the story is much less accusatory than Zarchi’s original.

That’s because, instead of seeing the rape as a result of standard male group dynamics, Monroe tries hard to decollectivize the guilt. In Zarchi’s version, the men were typical guys, and the rape, too, was therefore typical — a possibility for any man. In Monroe’s version, on the other hand, the rapists are individual monsters — a much less frightening idea.

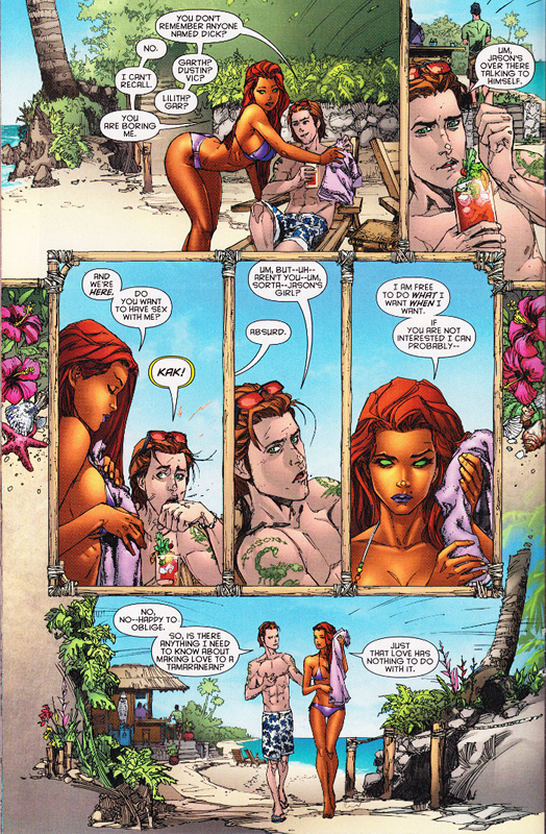

In the original (top), the rape is about the interactions between the men. In the remake (bottom) it’s about individual sadism.

Thus, for example, in the first film, when Jennifer first meets Johnny at the gas station where he’s an attendant, he’s nondescriptly polite with the distant friendliness of the perfect service employee. In the remake, on the other hand Johnny (Jeff Branson) is a lecherous jerk right from the get-go. Monroe even makes sure Jennifer (Sarah Butler) humiliates him explicitly (though accidentally) to add an additional personal motivation. This is carried through into the rape itself, in which Johnny devises elaborate humiliations for Jennifer — humiliations which are predicated on his commanding her to, for example, drink booze or show her teeth like a racehorse. There are no such commands in the original, and, indeed, there can’t be, since the rapists barely talk to their victim.. The rape, in other words, becomes about Johnny’s wounded vanity and his investment in elaborate sadistic games, rather than about the way the men perform for each other. In fact, in the first film, when Stanley starts to yell personal insults at Jennifer and generally to treat her as if she’s a person to be dominated rather than a piece of meat to be used, the rest of the men get more and more disturbed, and finally pull him away.

The remake turns Johnny into a sociopath; Matthew (Chad Lindberg), on the other hand, is given a conscience. His mental deficiency, the fact that he isn’t as much man, is, in Monroe’s version, a sign that he is not as evil or irredeemable as the others. There was no such shilly-shallying in the first film; there, Matthew’s incapacity simply made him less able to rape, not less eager to do so. When confronted by Jennifer in the second half of Zarchi’s film, Matthew does apologize and claim that the assault was not his idea…but Johnny and Stanley do the exact same thing when Jennifer comes for them.

Again, for Zarchi, the culprit is all the men and the way they interact, suggesting that violence against women is a systemic, social sin. For Monroe, though, Matthew really is sorry, while Johnny, even up to the moment of his gruesome demise, expresses no sorrow, feigned or otherwise. In the remake, the crime is a crime of individuals, which means some are more guilty than others and some (like Matthew or, the men in the audience) are less guilty.

Where the group dynamics completely come apart, though, is with the introduction of the sheriff. As I said above, his actions are inexplicable. We never even see him with the other men before the rape. He does mention that he’s known them since they were boys — but he’s in no sense their peer. We quickly learn (through a cell-phone call mid-rape) that he has a loving pregnant wife and a daughter in the honors program. He’s got, in other words, a lot to lose — and he’s willing to throw it all away for what? To have sex with some random city girl? To impress some subordinates?

In the first film, where it’s Johnny who has a wife and kids, Zarchi confronts this issue directly: Jennifer actually asks Johnny if he loves his wife while she’s seducing him. In response he says, “She’s okay. You get used to a wife after awhile, you know?” His family is a routine; it doesn’t particularly touch his inner life, to which, in any case, he seems to be only tangentially connected. The sheriff, on the other hand, is shown to be deeply invested in his child and his wife — he’s a doting middle-class family man. The idea that his spouse or daughter might find out about the rape sends him into a panicked rage. So what could possibly have led him to participate in a felony with a number of extremely untrustworthy accomplices?

We don’t know the answer to that question because the movie doesn’t tell us. And it doesn’t tell us because it doesn’t really care what his motives are. He joins in the rape because he’s the villain and, more, because it’s surprising. The sheriff is a plot device — a contrivance. Which means the real fifth rapist here is, in some sense, the director, who throws logic and coherence to the wind for the sheer pleasure of a cheap thrill.

Cheap thrills are what exploitation is supposed to be about, of course. But, while you certainly couldn’t say that Zarchi had a light touch, you also never felt that his hands were on the scales. This is part of the reason that the first I Spit on Your Grave had such an indelible, inevitable power. There weren’t plot twists or clever reversals; there was just sex and violence and their remorseless attendants, rape and revenge. Zarchi’s world fit together. Men were rapists. Rapists destroy women, and also themselves. QED.

Monroe, on the other hand, doesn’t believe any of that. His men don’t die because they’re rapists; they die because they’re in a movie and Monroe can do whatever he wants, damn it. In the remake, Jennifer doesn’t outthink the men because they’re sexist idiots and then dispatch them efficiently. Instead, she kills them because the script calls for her to turn into an avenging, unstoppable force of destruction — a petite Jason. From the moment she escapes her assailants by diving into a river and improbably disappearing, she ceases to be an actual person and becomes, like the Sheriff, a contrivance. Her revenges are much more elaborate than in the first film, but the rituals of torture aren’t her triumphs (or her degradations): they’re the directors’. A vision of essentially communal, and therefore political, justice has been replaced by individual punishment. Karma becomes deus ex machina.

It’s not really a surprise that a 2010 remake lacks the political charge of its 1978 prototype. The last thirty years or so have been rough on radicals, and while feminism has certainly made advances, the vision of apocalyptic, violent gender justice which inspired the rape-revenge films now seems both naïve and distasteful. As Terry Eagleton put it in his 2003 book After Theory, “Over the dreary decades of post-1970s conservatism, the historical sense had grown increasingly blunted, as it suited those in power that we should be able to imagine no alternative to the present.”

Perhaps the best demonstration of why a 2010 I Spit on Your Grave was bound to suck can be seen in another movie; Michael Haneke’s Funny Games. This film (in both its 1997 Austrian original and its 2008 American shot-for-shot remake) does not suck. It’s also not technically a rape/revenge. Instead, it’s a negation of the genre.

The brutality in Funny Games is flagrantly, explicitly unmotivated. In I Spit on Your Grave, humiliation and aggression is linked to gender politics — and also to class. The men in I Spit on Your Grave are hillbillies who resent Jennifer’s affluence, freedom, and economic power. This is shown most clearly in the 1978 film when the rapists, as part of their abuse, read sections of Jennifer’s novel-in-progress out loud, mock it, and then destroy it. Her work is, to them, not work at all, but a ludicrous affectation. (“I really despise people that don’t work,” Johnny says at one point, “they get into trouble too easily, you know?”) The movie does not suggest that these class antagonisms justify the rape, but it does show that they facilitate it. Economic imbalances, as any Marxist knows, are linked to violence.

In Funny Games, on the other hand, there are no economic gaps. At the beginning of the film, a comfortably upper-class family arrives at its lakeside vacation home. There, mom, dad, and son (Anna, Georg, and Georgie in the original) are trapped and systematically tortured by Paul and Peter two well-scrubbed young men with a passion for golf and sadism. The two torturers refuse to say why they are brutalizing their victims; when asked, they propound a series of more or less ridiculous scenarios (I was a poor child! I had sex with my mother!) which are clearly supposed to be bullshit.

Just as the film teases the viewer with reasons, it also teases them with rape — the two sadists force Anna to strip to her underwear, but never precede any farther than that. Most of all, though, it teases with revenge. Anna makes repeated attempts to escape and to turn weapons against her assailant. In the most startling of these moments, she actually manages to grab hold of a rifle and shoot Peter dead. At which point Paul finds a remote control and uses it to rewind the film to the moment before Anna shot his companion. He then casually takes the gun away from her

This flagrant breaking of the fourth wall can, of course, be seen as a way of (here it is again) implicating the viewer in the onscreen violence — of exposing our own sadistic and/or masochistic investment in tales of torture and brutality. And it does, certainly, show very nakedly the kind of narrative contrivance epitomized by the sheriff in the 2010 I Spit on Your Grave. Diagetically, it is the evil characters doing these things to these people we care about. But really it’s the director doing it for our amusement, which calls into question whether we in fact care about anything.

The use of the remote control is, though, not primarily an accusation of complicity. It’s an accusation of naivete. We in the audience are hoping the rape-revenge narrative will play out; that justice will be done. And the film mocks us for that — or (what is effectively the same thing) pats us on the back for knowing that such narrative justice is only a convention, not the truth.

Paul (Arno Frisch) knows the score in the original Funny Games

My hope that I Spit on Your Grave might have more of a feminist consciousness in a remade version was, then, clearly idiotic. The climate even for a film as vacillatingly feminist as the original I Spit on Your Grave has, it seems, evaporated. In current iterations of rape-revenge, violence is disconnected from causality, which means that it can call forth no real retribution. Some random God-surrogate pulls the strings and people suffer and that’s that. The best that can be offered as a political vision is a land in which people turn off their televisions to avoid political visions. Only suckers still believe that you can rise up against your oppressors and disembowel them with an outboard motor.