A little while back, Anja Flower wrote about gender identity in Ghost in the Shell. At the conclusion of zir essay, Anja argues that Ghost in the Shell, in its multiple marketing iterations and incoherence, can be read as undermining the idea of an essential gender.

Even laboring under the assumption that Motoko Kusanagi is bound by an underlying essence, we must admit that this binding essence is fictional – that in fact “Essential Motoko” is a construct we amalgamate out of images and ideas accumulated from consuming the Ghost in the Shell franchise in its various forms. Abandoning this idea, we are free to focus on the Major as she in fact is: a series of images and text snippets juxtaposed. Seen this way, gender can be read into just about everything: into the whole book, into whole characters to be sure, but also into scenes, pages, panel sequences, environments, color/tone palettes and individual colors/tones, outfits and items of clothing, poses, facial expressions, speed lines, patterns and symbols, inking techniques, even single lines. The changes in gendered expression from line to line, color to color, face to face, panel to panel are often tiny, but they are important because they provide an entirely different image of gender in comics. This image is not one of an immutable essence limited to characters and rarely or never changing, but as an everpresent jumble of tiny shards of signification, only semi-coherent at best and only even pushed into appearing as constant (if fluid) by the reader’s ability to imagine the gaps in information between panels – the device of “closure” described in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. Gender overgrows in every direction, abundant shards of it popping up wherever the particular reader’s subjectivity allows it; it is subjective, certainly, and also cumulative and temporal, agglutinating and morphing as the reader reads and re-reads, consumes new additions to the franchise, looks at new pieces of fan art, comes to greater understanding of plot points, digests criticism. Each of these experiences provides an abundance of these shards of gendering for the reader to plug into their gender-concept of the entire franchise, the individual story or character, the individual page. The reader is selective in doing this, and the shards from which they select appear different as the reader acquires different sets of eyes.

I hadn’t ever read Ghost in the Shell, but Anja’s essay intrigured me. My wife happened to have bought the manga, so I thought I’d read it and see what I thought.

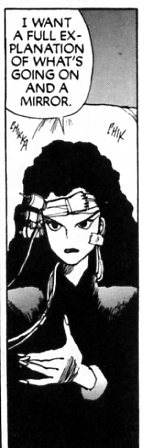

And what I thought was…well, to be honest, I kind of felt weird thinking anything about it. Here’s an example of why.

And here’s another:

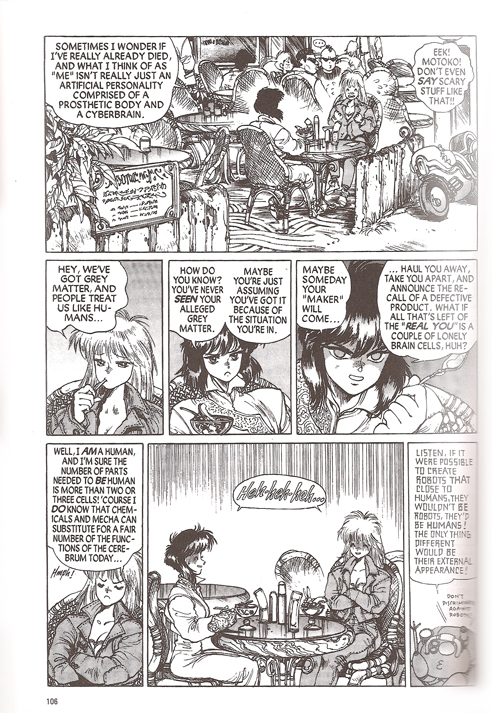

Or here’s one more:

Just looking at those panels, you might conclude that they were utterly anonymous genre fodder. The crusty but tough team leader fulminating hard-assedly; the ultra-competent fighter grieving through bluster hard-assedly; the sexy-tough couple bantering sexily but hard-assedly. You might think that there is nothing going on in this manga that you haven’t seen before; that character, plot, and atmosphere are little more than a half-hearted scrambling of tediously familiar topes.

You might think that. And you would, in fact, be right. Ghost in the Shell is, from beginning to end, an uninspired, barely stirred sludge of half-digested clichés. The plot is complicated, twisting, and aggressively irrelevant, bearing the characters along in a rush of technobabble from one uninvolving violent set-piece to another. The hyper-competent Major Motoko Kusanagi is a medical miracle, managing to fight, wise-crack, switch brains, and flash cheesecake without ever acquiring even the hint of a discernible idiosyncratic personality. When the mysterious, artificially generated Puppeteer merges with Kusanagi’s consciousness at the end of the volume, you wonder how on earth anyone is supposed to tell the difference. I guess Puppeteer/Kusanagi makes more speeches than Kusanagi alone did? That’s something I guess.

Kusanagi/Puppeteer — Still talking tough, still saying nothing.

The thing is, the fact that Ghost in the Shell is kind of lousy doesn’t necessarily undermine the points Anja makes. In fact, it’s lameness can in some ways be seen as thematic. The book, as Anja notes, is about the fracturing and fluidity of human identity; the characters are a mix of human, robot, cyborg, and combinations thereof. The page below from the manga (reprinted by Anja) lays out the theme — how can you tell whether you’re human or not? What does it mean to be human, anyway?

“what if all that’s left of the real you is a couple of lonely brain cells, huh?” Kusanagi asks.

The irony is that there aren’t even a couple of lonely brain cells here. No brain activity at all appears to have been expended on creating these characters. They speak and interact, but they have no real history or personality; they’re just sci-fi cyberpunk cyphers, mechanically running through their tropes. They wonder whether they’re real in the most artificial manner possible. Are they pasteboard cliches dreaming that they’re robots, or robots dreaming that they’re pasteboard cliches?

Genre’s inherent emptiness can often be an excellent way to look at the way the world doesn’t work. This happens in Gantz, where the incoherence of the genre elements fits into a supposedly cynical, but arguably terrified nihilism. It happens in Moto Hagio’s story A Drunken Dream, where the standard narrative warps and fractures before an underlying trauma.

For Anja, I think something analogous happens with Ghost in the Shell. The fact that Kusanagi is a blank slate emphasizes the narrative’s half-denied intimations of open identities. The book claims that inside every body, of whatever sort, there is a ghost or essence. But despite this, Kusanagi is, for practical purposes, no one — the Puppeteer takes over an empty puppet. The self is not a fixed core nailed to a single gender; it’s a series of shards that come together in this way and that. For Anja, that lack of essence is (at least potentially) freeing.

For me, though — I mostly find the implications of Ghost in the Shell depressing. I don’t have anything in principle against fluid identities…but in Ghost in the Shell, those fluid identities seem to be not so much liberating as claustrophobic. You can be anyone you want…as long as the person you want to be is a stereotypical tough-talking government agent, scrambling blandly through some bone-headed plot. To give up your essence in this context doesn’t open up infinite possibilities. It just makes you generic. Abandoning your self doesn’t let you escape social conventions and expectations; on the contrary, it means you have no choice but to embody them.