A much-shortened version of this review ran last week in the Chicago Reader. I also had an essay here a little bit ago about some other reactions to the book.

_____________________________

It’s because I do see sex as sacred and potentially spiritual that I believe in commercializing it and making this potentially holy experience more easily available to all.

That’s Chester Brown , writing in the lengthy appendices to Paying For It, his graphic memoir about his experiences as a john. The quote is odd not so much for what it says as for what it doesn’t. Specifically, throughout the book Brown sets himself firmly against the ideas of romantic love and marriage, and touts sex-as-commercial-experience not just as a reasonable arrangement for him, but as the best arrangement for everybody. What, then, exactly, is the sacred nature of sex for Brown? Or, to put it another way, if the sacredness of sex isn’t about love, what’s it about?

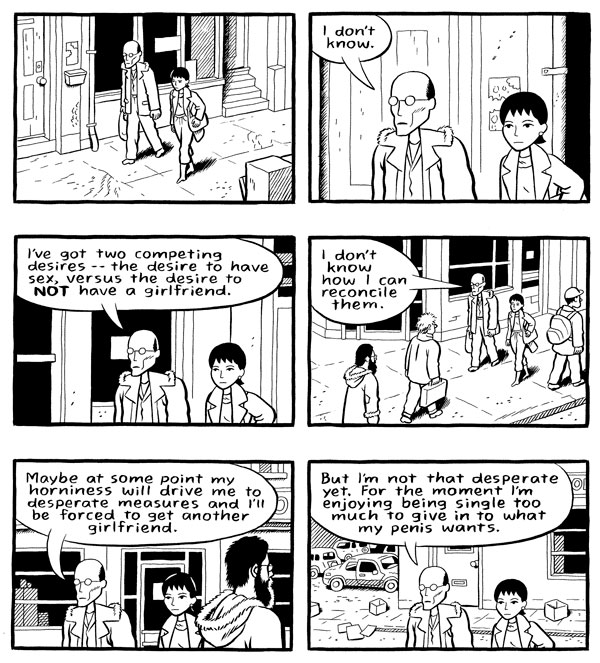

In some ways, you could see Brown’s entire book as an answer to this question. The narrative starts as he and his girlfriend, Sook-Yin, go through an amicable break-up, and he realizes he doesn’t want to have a romantic relationship ever again. In fact, he decides that romantic relationships are actively bad. “…being in a romantic relationship brings up all [Sook-yin’s] insecurities,” he notes. “It does that for everyone — me too.”

Convinced of the evils of romance, yet not willing to give up on having sex, Brown eventually decides to get some the old fashioned way — by paying for it. As he learns the ins and outs of being a john (how to find an escort, when to tip, where to look for reviews online) he also becomes a more and more adamant proponent of legalization. The graphic novel alternates between Brown’s encounters with different “whores” (as he sometimes calls them) and his arguments with friends, family, and the prostitutes themselves about the morality of prostitution.

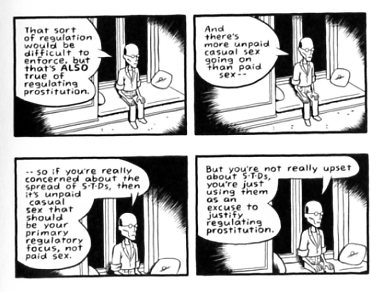

These arguments, continued in the appendices and notes, are by and large quite convincing. Admittedly, I’m biased — I thought criminalizing sex-work was a bad idea before I started reading the book. Even so, Brown pushed hard against my already-very-liberal opinions. He argues forcefully that prostitution should be not only legalized, but completely unregulated. In the appendix, for example, he points out that legal prostitutes in Nevada often aren’t allowed to leave the brothel without permission, and are sometimes forced to buy condoms and even food from the brothel-owner at exorbitant prices. These women, then, are much more exploited than they would be if they weren’t regulated, or even than they would be if they were just working illegally. Brown is also compelling when he insists that prostitutes should not be subject to mandatory health testing. “Medical treatment,” he says to his friend, the cartoonist Seth, “should always be voluntary. It should never be forced on anyone.”

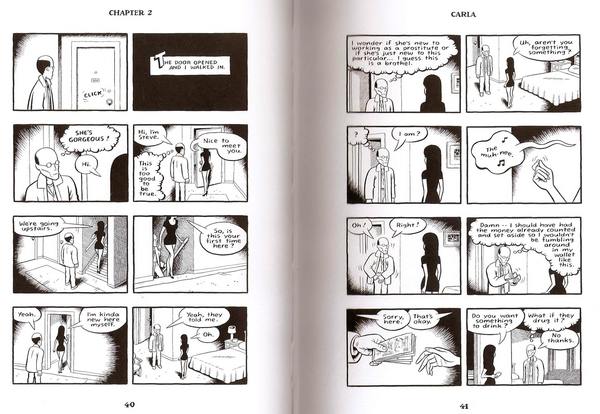

But while Brown’s words make a strong case for the dignity and necessity of legalized prostitution, his comic itself is, seemingly unintentionally, more ambivalent. This is most noticeable in the portrayal of the prostitutes themselves. Brown, of course, uses fake names for all of them. He also, as he notes in the foreword, deliberately removes any reference to their real lives — boyfriends, children, childhoods, families. “I wish I had the freedom to include that material…,” Brown says, “it would have brought the women to life a full human beings and made this a better book.”

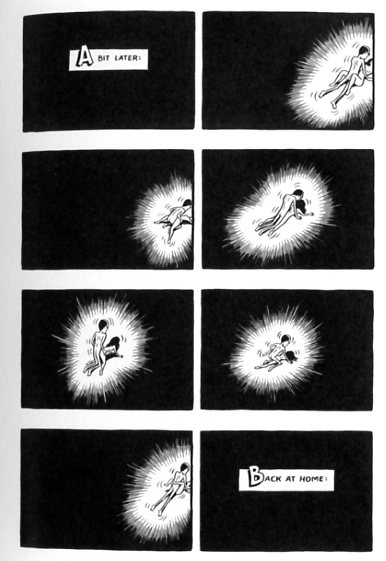

That’s no doubt true. But one could argue that, despite his protests to the contrary, Brown actually goes out of his way to dehumanize the women he sleeps with. Specifically, he never shows their faces. Presumably, this is meant to protect their anonymity — but he’s drawing them. He could change their faces, just as he made them all brunettes. By showing us only the backs of their heads, he turns them all into expressionless ciphers. His trysts with them seem like ritualized encounters with dolls. This is even more the case since Brown rarely varies layout or style; his comics are series of small squares, often with minimal backgrounds. His representations of sex, similarly, have a regimented similarity; he and the woman are placed against a black background, fucking with the joyless, repetitive deliberation of wind-up dolls.

Brown’s depiction of himself is even more disturbing. A thin man, he draws himself as a death’s head, his glasses staring blank and pupilless. And then words start to robotically issue from that cadaverous skull, reasoned arguments grinding forth like the granite lid scraping across a tomb. “Romantic….love…is…evil…*click* marriage…is…evil…*click* there…is…only…money…and…desire…click*”

Brown has, in short, turned himself into an uncanny libertarian caricature. And it is this libertarianism — along with its forefather, enlightenment utilitarianism — which forms the basis for his dislike of romantic love. Romantic love, he argues, “causes more misery than happiness.” It is wrong because its calculus is wrong; instead of maximizing joy, it interferes with the cheerful autonomous operation of the individual. Brown touts his own long-term, monogamous relationship with a prostitute named Denise precisely because it is entirely based on his own desire, rather than on potentially traumatizing reciprocity. “I’m having sex with Denise because I want to, not because I made a marriage vow to her or because she’d get jealous because I saw someone else.”

And this, I think, is why Brown sees sex as sacred. It’s because sex, especially paid sex, is divorced utterly from commitment or community. As a libertarian, he worships the individual, and sex is the ultimate expression of the individual autonomously pursuing pleasure. Brown even argues that prostitution, once legalized, should not be taxed. The government and, indeed, society has no place in the bedroom. Sex is sacred because it is private.

The irony here is that Brown thinks that he’s somehow challenging the basis of romantic love. The truth, though, is that he is merely carrying that logic of romance through to its conclusion.

In the 1978 essay, Sex and Politics: Bertrand Russell and ‘Human Sexuality,’ theologian Stanley Hauerwas notes that

marriage can be sustained only so long as it is clear what purposes it serves in the community which created it in the first place. With the loss of such a community sanction, we are left with the bare assumption that marriage is a voluntary instituion motivated by the need for interpersonal intimacy.

Romantic love, as Hauerwas says, is already an ideology of autonomous atomization. It assumes that you marry for love, and that love is an ideal because it is personally fulfilling. Brown does not dispute the liberal, capitalist goal of personal fulfillment; he just argues that liberal, capitalist fulfillment is ideally maximized by the market.

That’s a logical position, obviously. Indeed, its so logical it starts to verge on madness. If everyone is an entirely independent desiring subject in theory, then in practice everyone is an object, reduced, like Brown’s prostitutes, to blank toys manipulated for everyone else’s mechanical satisfaction. That’s true whether we’re trying to maximize our individuality through romantic love or through the sacred orgasms of capital. If we want a less soul-crushing sexual ethic, we may need to consider the possibility that sex is about other people, and possibly about God. In the meantime, I guess, like Chester Brown, we can look forward to life as happy, fulfilled, free-spending skulls.

______________________

Addendum: I didn’t have space for this in the initial review, but I did want to highlight what I think is one of the most interesting interchanges in the book. Brown is talking post-coitally to a prostitute named Edith. Brown explains to her that he no longer believes in romantic love, which is why he visits prostitutes. He outlines the arguments I’ve already discussed, emphasizing especially that people change over time, and that it’s not fair to either partner to be tied down to a romantic relationship when both will eventually change.

The end of the conversation is as follows:

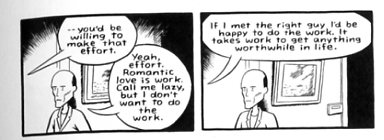

Edith:Yes, but you can try to continue to understand your partner. And if you love him or her you’d be willing to make that effort.

Brown: Yeah, effort. Romantic love is work. Call me lazy, but I don’t want to do the work.

Edith: If I met the right guy, I’d be happy to do the work. It takes work to get anything worthwhile in life.

What’s interesting here is that Edith gets the last word, her dialogue floating above Brown’s inevitably expressionless stare. Brown never makes any attempt to refute her — not in the narrative, not in the notes (which don’t mention this exchange at all.)

I suspect the back and forth with Seth will get more attention for various reasons (it’s longer, it’s Seth.) But this is the moment in the book where Brown comes closest to letting someone get the better of him. Edith’s argument — that relationships are about work, and that that is in fact what makes them worthwhile — is a fine thumbnail paraphrase of Hauerwas’ position, and Brown, apparently, has no response to it.

There’s a nice irony, too, in the fact that Edith, who is extolling the virtue of work, is in fact working as she speaks. The sequence get at the class divide between Brown (artsy middle-class hipster with disposable income) and the women he’s seeing, and raises the question — largely unexamined in the book — of privilege.

I don’t think that Brown is actually endorsing Edith’s position. The rest of the book makes it quite clear that yes, he really does think prostitution is the ideal way to conduct sexual relations. Even when he admits that he is in love with Denise, he does so by arguing that paid sex is the ideal expression of, and venue for, that love. Still, he’s to be commended for giving someone else a chance to put forward a contrary view; that you get, not what you pay for, but what you work for.

______________

Update: Naomi Fry’s review at tcj.com posted today touches on some of the same issues discussed here.