This first appeared on Splice Today.

__________

The English Teacher, the new romantic comedy starring Julianne Moore, is set in Kingston, PA — my hometown. Or at least, it’s supposedly set there. I’m well aware that films have only a tangential, arbitrary relationship to reality — but still, it’s disorienting to see your childhood misrepresented with such vacant deliberation.

As far as its plot goes, it’s not entirely clear why The English Teacher had to be set anywhere in particular. Dreamy, spinster English teacher Linda Sinclair (Moore) encourages a former student, Jason Sherwood (Michael Angarano) to have the high school drama club put on his play. Then there is sexual tension, followed by humiliating complications, followed by learning life lessons and a maybe happy ending with Jason’s dad (Greg Kinnear.) My wife figured out who was going to sleep with who and in what order pretty much as soon as the cast walked on the screen.

The by-the-numbers plot required, apparently, a by-the-numbers setting. And so, Kingston, PA, becomes a pretty, middle-class town, filled with pretty, racially diverse people and cute bookstores and coffee shops and enormous, elegant houses which are somehow, apparently, affordable on an English teachers’ salary.

The Kingston I knew was somewhat different — and while I haven’t been home in a long time, nothing I’ve heard from folks who have suggests that it’s changed that much.

The Wyoming Valley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, where Kingston is located, is an old coal-mining area, hard-hit by deindustrialization. The population is mostly white ethnic immigrants — I had a lot of teachers with names like Lanunziata and Wisniewski, not so many with names like Sinclair. Demographically, it’s also old; when I was living there, Wilkes-Barre/Scranton had the highest average age in the country outside of Miami. You walk down a random street in the Wyoming Valley, you’re much less likely to see a cute little bookstore than a funeral parlor. Or a fast food joint. I vividly remember waiting for a plane in the Wilkes-Barre International airport and hearing some businessman explaining why his firm had located in the Valley. “Ours is not a low-cal product,” he said.

The film was not actually shot in Kingston, and in some cases, it’s clear enough why director Craig Zizsk didn’t try for more verisimilitude. Who wants lots of shots of elderly, non-slender people wandering around in the background, much less the foreground, of your feel-good romantic comedy? In real life, no administrator could just up and fire a teacher in the Wyoming Valley’s thoroughly unionized schools, the way Vice-Principal Phil Pelaski (Norbert Leo Butz) does. But you’ve got to have drama. I get that.

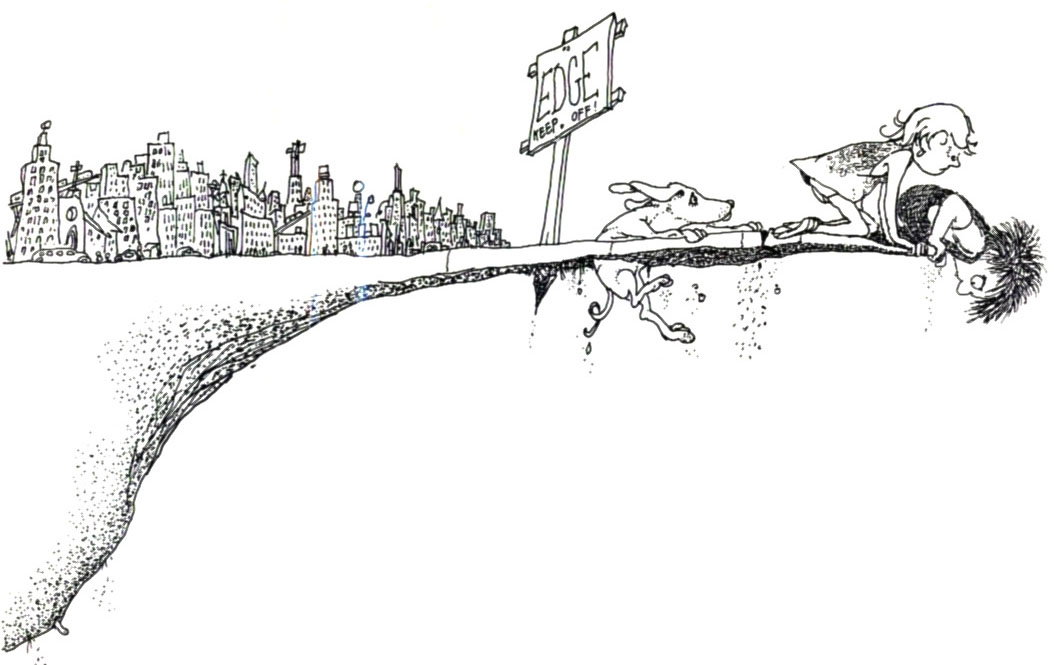

In other respects, though, it seems like the film would have been strengthened, not weakened, by a greater attentiveness to the putative setting. One of the ways we know that Linda Sinclair is sheltered and repressed, for example, is that she’s spent her whole life in Kingston. In real life, the Wyoming Valley is a place where families stay for generations. My dad would often say that even after living there for 20 years, he and my mom were still treated like newcomers. But it’s also a place from which young people looking for jobs and cute coffee shops want to escape. Allowing Kingston to be something closer to Kingston would make Linda’s life choices more pointed. It would also sharpen Jason’s angst about the fact that he had to return home after failing as a playwright in New York. And surely there’d be some humor to be had if, say, Jason had sat down at a desk while discussing his sophisticated play, and discovered, hidden inside it, a cup of brown chew spit. That would have been some local color.

The film , though, beyond a few place names, isn’t interested in local color. Especially if that local color has anything to do with class.

A couple of months back, Christopher Orr argued at the Atlantic that romantic comedies are bad these days in part because class doesn’t work as a barrier to couples getting together any more. I’ve expressed skepticism about this before, and The English Teacher only confirms my sense that class has not disappeared for Americans, whether in romance or anywhere else. After all, if class is such a non-issue, why bother going out of your way to erase it? If economics has nothing to do with rom-coms any more, why does this film need Kingston to be so blandly middle-class?

Part of the reason may be the film’s nervous relationship with realism. Linda is characterized by the insistent voice-over as a romantic, too lost in her reading and dreams for authentic relationships. Those authentic relationships, being, in this context, the formulaic plot of rom-com.

Perhaps the filmmakers were afraid that if they took that plot out of nowhere USA and put it in a real (or even real-ish) setting, people might notice that Linda was just exchanging one hollow falsehood for another. Maybe, in other words, the problem with rom-coms isn’t that class has ceased to matter to us, but rather that the genre has become so decadently enmeshed in its own increasingly rigid and self-referential tropes that it can barely find its own ass, much less northeastern Pennsylvania.

Which is too bad, because, while it had problems like any real place, northeastern Pennsylvania has a good bit to recommend it too. There’s no such school as the film’s Kingston High School, but Wyoming Valley West High exists, and I had some excellent teachers there. The Wyoming Valley itself, set in the Appalachian mountains, could be really beautiful too. Even the giant coal slag heaps that sat there for decades had a certain grimy grandeur. I don’t exactly miss it, and I’m not sorry I left. But I’m glad I grew up there, rather than wherever The English Teacher is set, even if the teachers there all look like Julianne Moore.