This first ran in Splice Today.

_____________

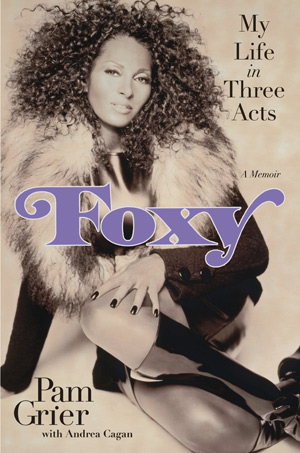

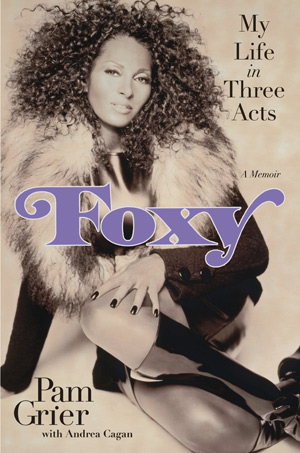

You’d think Pam Grier’s life would make for a fascinating memoir. Raised working class and rural, subjected to racial discrimination throughout her childhood and raped twice, she nonetheless, through sheer determination, smarts, and astonishing good looks, managed to carve out a career as an actor. Her iconic presence in some of the most successful and influential blaxploitation films made her perhaps the screen’s first female action hero. And along the way to semi-stardom, she dated luminaries like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Freddie Prinze, and Richard Pryor, survived breast-cancer, and hobnobbed, it seems, with everyone who was anyone, from Sammy Davis Jr. to Fellini.

So, like I said, there seems to be a lot worth reading about there. And Foxy: My Life in Three Acts certainly is affecting in parts. As the father of a six-year-old, I found Grier’s account of being raped at that age actually nauseating. Less somberly, Grier’s discussion of one of her visit’s to the gynecologist has to be one of the top gossip anecdotes of the year so far. In her account, Grier explains that the doctor discovered “cocaine residue around the cervix and in the vagina” and asked Grier if her lover was putting cocaine on his penis. “ Grier responds, “That’s a possibility…. You know, I am dating Richard Pryor.”

Then she admits to the doctor that during oral sex her lips and tongue go numb because, apparently, Richard Pryor did so much coke that it made his semen an opiate.

And yet, despite such moments of interest, the memoir overall is surprisingly flat. Anecdotes are dutifully hauled out — here’s Grier with her church choir at ground zero of the Watts riots; here she is singing with a drunk John Lennon. But the memoir stays on the surface; you get little sense of Grier’s inner life, ideas, or passions. Her discussions of racial and sexual prejudice are for the most part innocuous boilerplate. There are some hints that she has ambivalent feelings about the exploitive elements in her early roles, but those issues are never really explored. She’s politely reverent towards most of the stars she comes across, from Paul Newman to Tim Burton.

Part of the failure here is no doubt the fault of co-writer Andrea Cagan, whose prose never rises above competent. But the main problem is Grier’s personality. In a couple of places in the book Grier notes that she’s a “private” person — which is, like much in the memoir, a significant understatement. Grier is not merely private; she is fiercely, even remorselessly, adamant about protecting her personal boundaries. When one of her first serious romantic interests, the sexy, talented, wealthy, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, tells her he loves her and asks her to become a Muslim so he can marry her, she takes her time…thinks about it…and finally says no. When the sexy, talented, wealthy, but frighteningly coked-up Richard Pryor wants a serious relationship with her, she takes her time…thinks about it…and eventually walks. In 1977, Freddie Prinze — with whom she’d broken up two years previously — called her to say that he had bought a gun, was thinking of using it on himself, and needed her to come help him. Though she was staying only a few blocks away from his hotel, she refused to go see him. Three days later he committed suicide. Grier notes that she was “heartbroken” and, for a while, guilty, but ultimately concludes “I wanted to save his soul, but I knew that only he could help himself, and he hadn’t really wanted to.”

My point here isn’t to condemn Grier for callousness — on the contrary, all the decisions above seem absolutely reasonable. Abdul-Jabbar, while possessed of many fine qualities, seems to have been a controlling asshole. Similarly, Richard Pryor was, clearly, one of the most catastrophic train wrecks of the decade, if not the century. And even the phone call from Freddie Prinze — your ex with a megacocaine problem calls you up to tell you he’s got a gun and is feeling paranoid, please come over? I don’t think you can be faulted for saying, “you know what? No.”

A U.S.A. Today blurb on the back of Foxy declares “Pam Grier is a survivor.” When you read that, you think of her fierce characters in Coffy or Foxy Brown — fighters who took on incredible odds and beat the system. The thing is, though, in real life, survivors aren’t like that. If you take on incredible odds, you usually lose. Somebody who is going to survive has to pick her battles very carefully — and realize that usually, the best defense is actually just defense. Again and again throughout the memoir, Grier protects her safety and sanity not by embracing violence or revenge, but by refusing to do so. When she is date-raped at 18, she doesn’t tell her family because she fears that if she did, her male relatives would kill her attacker and end up in jail. As an adult, when her cousin and best friend, dying of cancer, asks Grier to read out-loud in church a manifesto attacking her abusive husband, Grier refuses. “I couldn’t open so many wounds and deal with the aftermath,” Grier writes. “I refused to be the one to read the letter and stir the pot — a decision I regret to this day.”

Again, I’m not judging — these are incredibly difficult choices, made under extreme duress, and I don’t think anyone but Grier is in a position to decide whether she did the right thing, or whether there was even a right thing to do. The point, though, is that in most every instance, Grier’s instinct is to avoid stirring the pot — and stirring the pot is exactly what you want to do in a book like this. The most successful celebrity memoirs — such as Jenna Jameson’s riveting and surprisingly insightful 2004 How to Make Love Like a Pornstar — are shameless both in their self-revelation and in their skewering of others. Pam Grier, despite all those exploitation films, doesn’t appear to have a shameless bone in her body. The qualities that allowed her to get where she did — her reserve, her poise, her dignity — are the very things that make Foxy so underwhelming. Still, even though as a reader I was disappointed, I can’t really find it in me to wish that the memoir was better If you have to choose one or the other, after all, a successful human being is surely preferable to a successful book.