Reading Joe Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza, I kept coming back to the same question. Namely — journalism as comics? Why? Sacco’s project — interviewing individuals in the Gaza Strip who were witnesses to two different Israeli massacres in 1956 — could easily have been presented as an agitprop book or as an agitprop documentary film. His methodology — the careful documenting of atrocities, the humanizing of the enemy, the nuanced by firm advocacy for the powerless — are all familiar tropes and tactics of left-wing investigative print and film journalism. Given that the content is familiar, what exactly does the comics form add? Why bother with it?

It’s a question that’s likely to make comics fans bristle. After all, to turn the question around, why should comics have to justify itself while other forms do not? Shouldn’t the success of the endeavor be more important than the medium?

Perhaps. And yet the question persists…in part because when you’re doing Joe Sacco’s brand of journalistic advocacy, journalism in prose and journalism in video have some major, easily apparent advantages over journalism in comics. Prose is unobtrusive and easily distributed; a Human Rights Watch report, for example, can provide facts and talking points with minimal fuss, and can also be readily quoted, linked, and copied, spreading a targeted, clear, footnoted message to as broad a range of people as possible. Film, on the other hand, can provide a sense of presence and urgency which is difficult to duplicate, allowing witnesses to speak in their own words with an authority and resonance that is very difficult to duplicate.

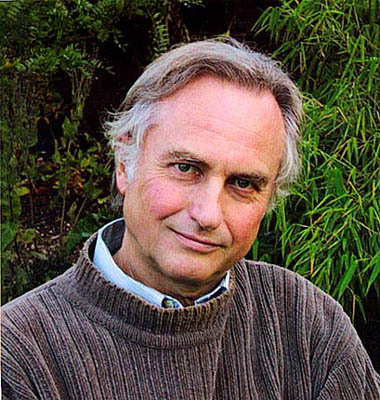

The advantage of prose or of film can perhaps be summed up as “authenticity.” Journalism’s goal is to show truth, and so spur to action. Prose and film are, for historical and formal reasons, often seen as at least potentially transparent windows on truth. Comics, on the other hand, foregrounds its artifice; as Sacco mentions in his introduction, everything you see on the page is rendered by his hand. And this is, incidentally, why Sacco is seen as an artist, rather than just as a reporter. Certainly, nobody that I’m aware of has ever referred to an HRW report as the work of a mature artist who has found his own style and voice, which is what friend-of-the-blog Jared Gardner called Sacco in his review of Footnotes in Gaza.

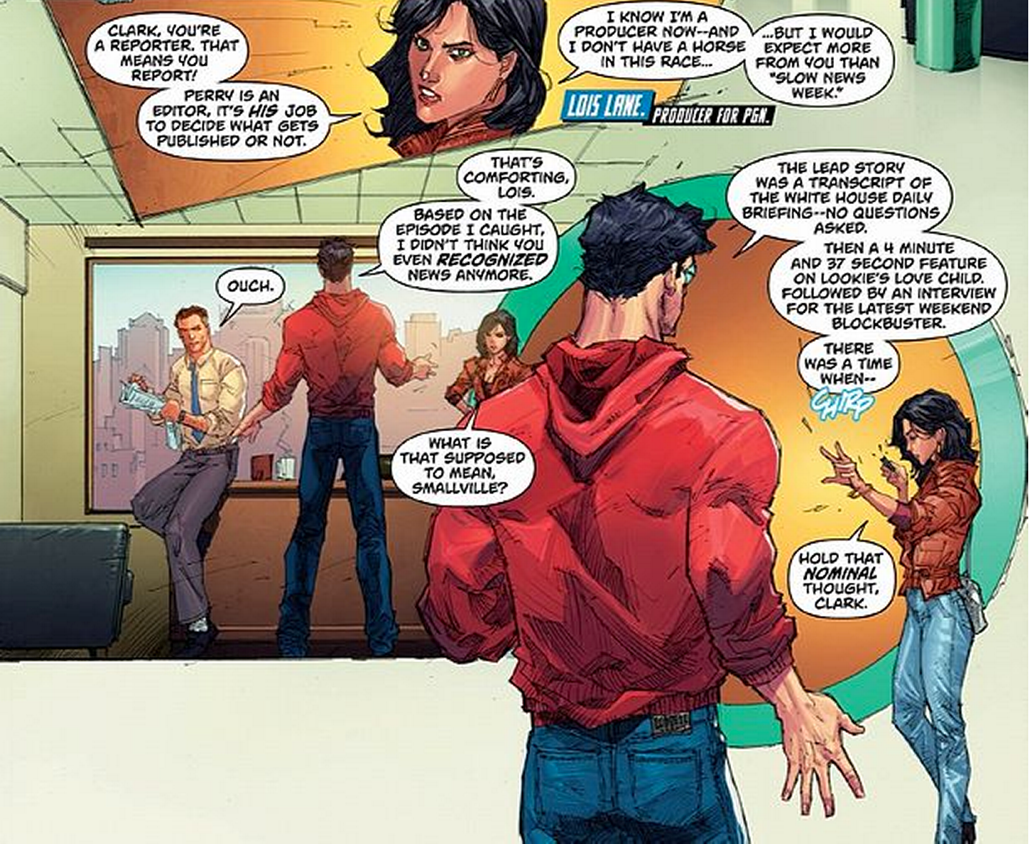

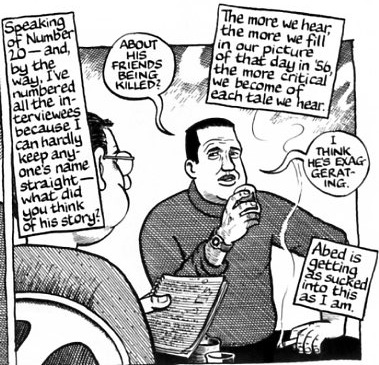

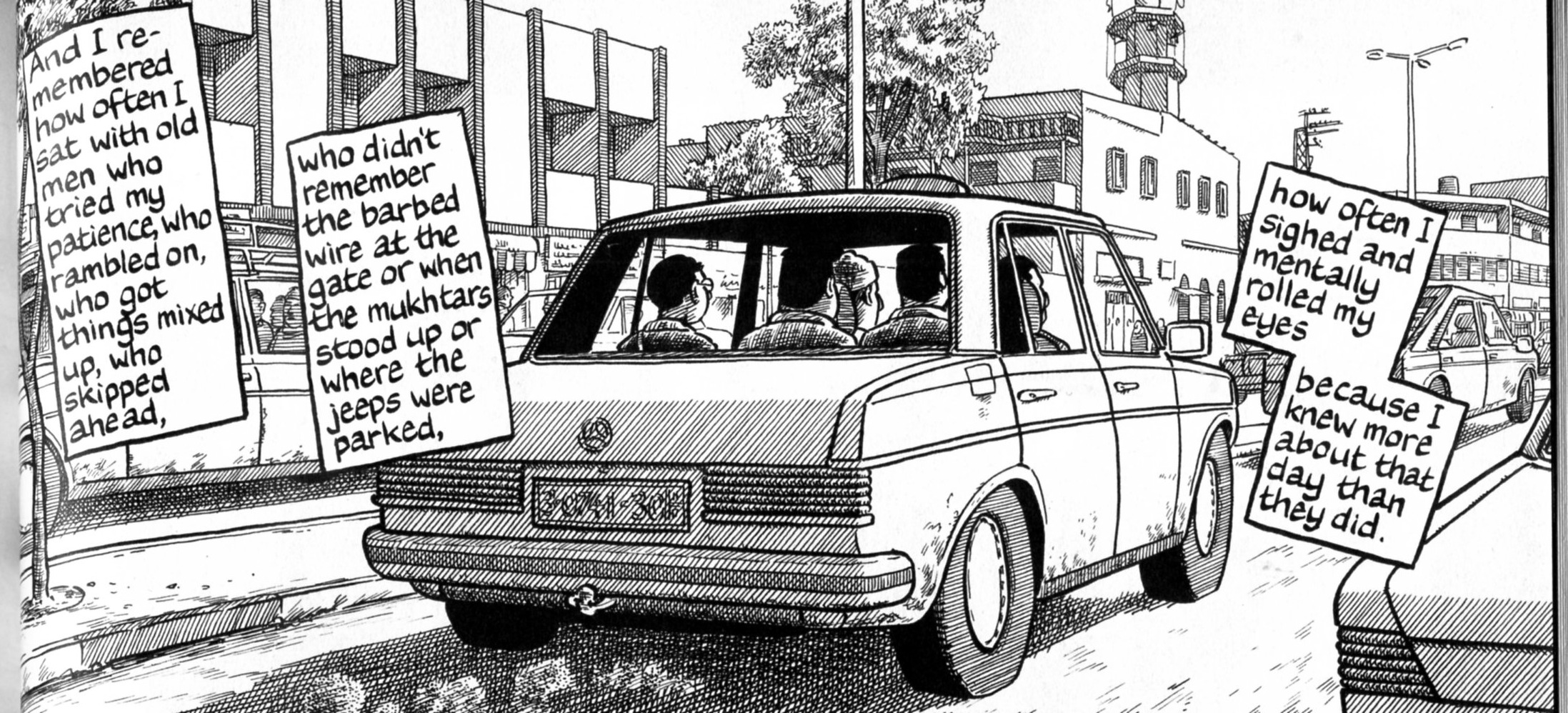

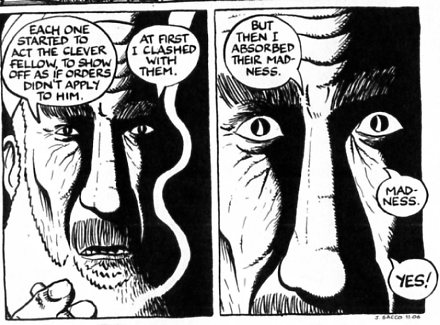

One upshot of making journalism comics, then, is to make journalism art, and to make the journalist an artist. The downside of this is that you then end up in a situation where the genius and sensitivity and angst of the journalist ends up pushing to the side the suffering and injustice which is the journalism’s putative subject. Sacco is certainly aware of this danger, and makes moves to undercut it, or problematize it, as on this second-to-last-page of the graphic novel.

However, I don’t think these gestures are ultimately successful. In this case, for example, indicting himself for insensitivity and hubris ends up validating his sensitivity and honesty, and also makes the book as a whole about his psychodrama and growth — about his experiences in Gaza, rather than about the experiences of those who are stuck in the place on a more permanent basis. In this context, contrition for selfishness still ends up as a way for the self to take up more space. The comics form has allowed/impelled Sacco the journalist to become Sacco the genius.

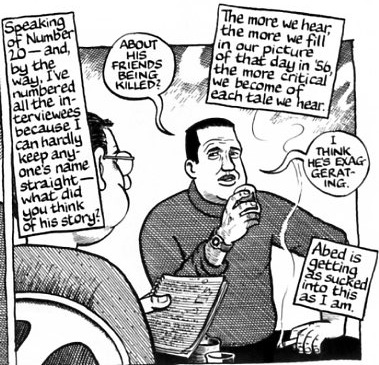

But while the artifice of comics journalism has its downsides, it has some advantages as well. Most notably, Sacco’s narrative is in no small part about the uncertainty of memory and of history. Comics, precisely because of its unfamiliarity as journalism, is less transparent; it demonstrates, almost reflexively, that journalism is not “truth,” but an effort to reconstruct truth.

Again, precisely because comics is a less familiar form for journalism than film or prose, it ends up emphasizing its own artificiality. Everything you see in Footnotes in Gaza is created and represented by Joe Sacco. His account always has a built in asterix. What he shows you is not what happened, but a collage stitched out of the words and memories of his interviewees and the fabric of his own visual imagination.

Sacco uses comics, then, to emphasize subjectivity. But…do you need to use comics to do that? Writers have been exploring the wavering, difficult nature of truth and of history for hundreds of years in prose, surely. Joseph Conrad’s narratives within narratives within narratives, or Paul Celan’s bleak koans hovering on the edge of comprehensibility, to cite just two examples, seem like more challenging and more thoroughgoing efforts to wrestle with the intersections of meaning, subjectivity, and historical trauma. For that matter, those Human Rights Watch reports I mentioned are usually pretty good about discussing the difficulty of gathering evidence and the conflicting testimony of witnesses. Do we really need the comics form to tell us that human memory isn’t perfect?

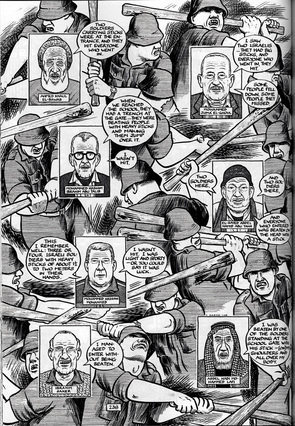

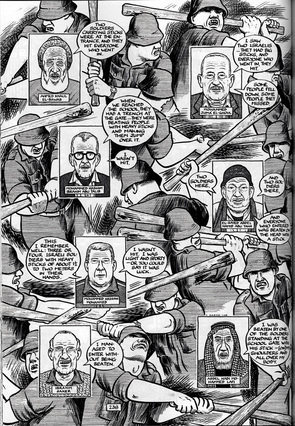

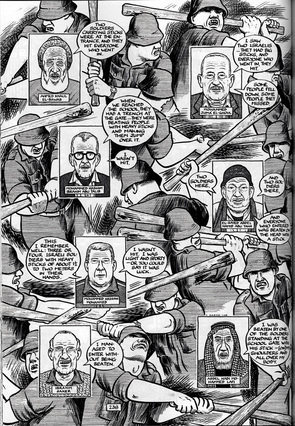

Indeed, the use of comics seems in some ways like a epistemological shortcut. Subjectivity can be linked to, or summarized as, the comics form, which is shown as obscuring the objective truth of reason and trauma. Comics may serve to call reportage into question…but it also, at the same time, validates or stabilizes the reportage. Thus, in that page above, the images of the Israeli’s swinging clubs are imaginative, or unverified…and their unverifiedness contrasts, or highlights, the more vouched veracity of the portraits, which are (at least probably) photoreferenced. And the referenced images, in turn, highlight the even greater veracity of the words, taken down from (presumably taped) interviews. Thus, while the comics form may initially appear to highlight subjectivity, it could instead be said to create a fairly clear hierarchy of representation, in which Sacco’s deployment of his research materials and his illustration signals the reader what is “truth” and what is less so.

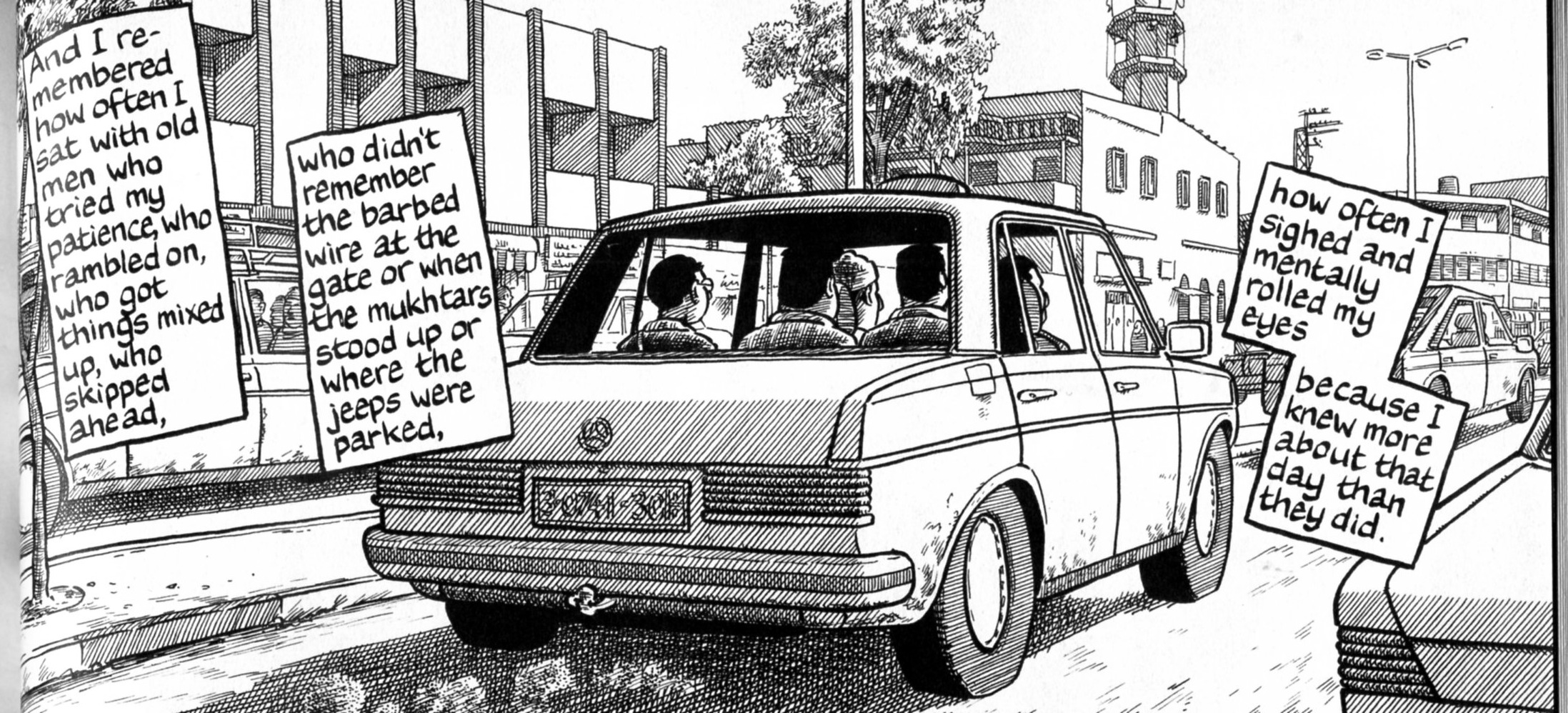

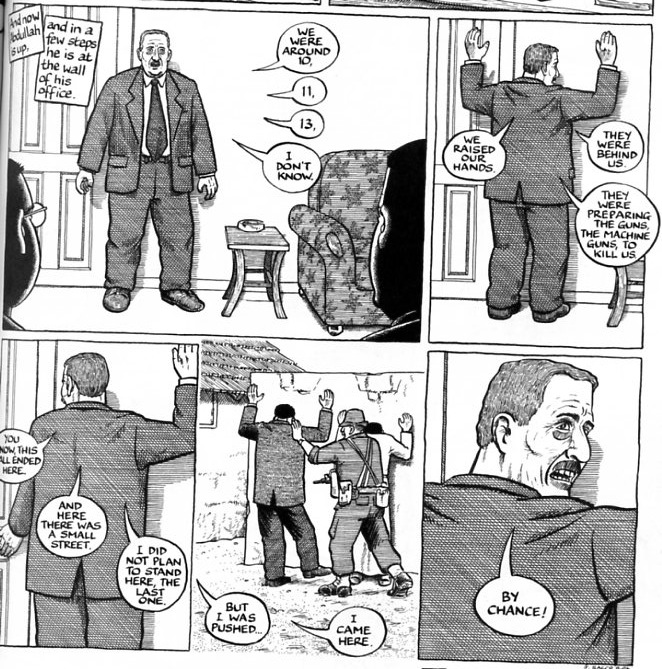

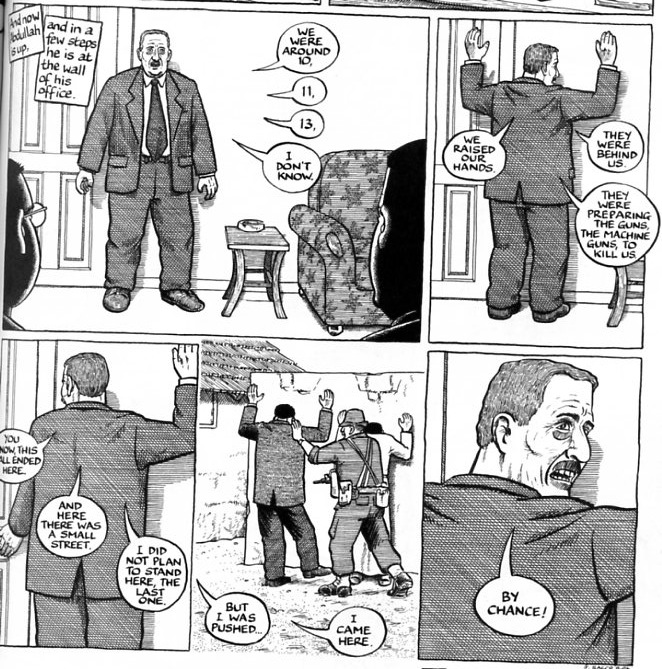

This isn’t necessarily a weakness. You could argue that comics’ strength as journalism lies not in its artificiality per se, but rather in the ease with which it can evoke differing degrees of artifice; in the resources it has available for signaling truth or falsehood, or different levels of both. For example, one of the most interesting aspects of Sacco’s book is the way that he shifts back and forth between the 1956 atrocities and the ongoing violence on the West Bank. For comics, where still images evoke time, it is relatively easy to make two times equally physical and equally present.

Comics’ ability to show bodies discontinuous in time is used here to show trauma across decades; the self from the past is as real as the self in the present. That is, it’s not entirely real, but is composed of representation and memory, the present self made of a past self, as the past is made of, or created out of, the present.

The problem is that Sacco’s manipulation of artifice and memory is not always so deft. In that page we looked at earlier, for instance:

The cartooning turns the Israeli soldiers into deindividualized, snarling bad-guy tropes, all teeth and slitted (or entirely obscured) eyes. Is this how the Palestinian’s are supposed to have seen them? Or is it how Sacco sees them? And is the acknowledgedly subjective nature of comics supposed to make us question this demonization? Or is it supposed to excuse it? Or, as perhaps the most likely possibility, has the impetus for dramatic visuals been catalyzed by comics’ history of pulp representation to create a pleasing collage of villainy from which readers are encouraged to pleasurably recoil?

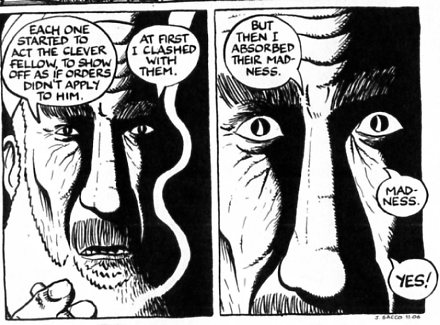

Or another example:

This is one of a number of times when Sacco zooms in on a grizzled Palestinian fighter, dramatically showing us his crazy eyes. As with the thuggish snarling Israelis, the formal contribution of comics here has to do less with emphasizing subjectivity and physicality, and more to do with the pleasures of pulp tropes. It’s Sacco’s own “Muslim Rage!” moment.

From this perspective, the advantage of comics as a form may be less the meta-questioning of the journalistic project, and more its unique ability to present itself as serious art while simultaneously coating its earnest reportage with a sugary dab of melodrama. One can debate whether this is ethically or aesthetically desirable, but either way it’s clear that Sacco’s comics provide something — a mix of high-art validation and accessible low-art hints of pulp — that is uavailable in prose or video long-form journalism. I don’t necessarily like Footnotes in Gaza that much, but I have to grudgingly admire its creator’s marketing instincts in finding and exploiting such an unlikely genre niche.