40 Years of the Same Damn Story, Part 2

One of the most popular and enduring Yuri tropes is that of the “Girl Prince.” While it’s probably impossible to fully remove the Girl Prince from the role of “butch” in current Yuri fans’ minds, today we’re going to look at the literary and theatrical roots of the character and see how she has changed over time.

The Girl Prince can be traced back as least as far as the Torikaeabaya, a Heian tale of brother and sister who are naturally more aligned with the roles assigned to the other gender. They switch places at the Heian court and drama ensues. The princess of the story makes a spectacularly good prince until she falls in love and is undone by pregnancy, a theme that is echoed in many a western tale of female cross-dressers.

The Girl Prince can be traced back as least as far as the Torikaeabaya, a Heian tale of brother and sister who are naturally more aligned with the roles assigned to the other gender. They switch places at the Heian court and drama ensues. The princess of the story makes a spectacularly good prince until she falls in love and is undone by pregnancy, a theme that is echoed in many a western tale of female cross-dressers.

In the 1920s, a musical theater troupe was formed to bring travelers out to a small town in western Japan. The town, and the troupe are called Takarazuka. The troupe was created as an all-female group, with roles of men being played by Otokoyaku, a term commonly understood to be the popular culture analogy to the Onnagata (men who play female roles) of the high culture Kabuki theater.

Otokoyaku not only play male roles on stage, they are required, to some extent, to play the man 24/7. To these western eyes, the “men” of Takarazuka appear exaggerated, clownish lampoons of men. They stand aggressively, speak harshly, but make love tenderly, like the hyper-masculinized men of romance novels.

James Mitchener’s Sayonara provides a post-WWII male perspective on the cultured elegance and “masculine” mannerisms of the Otokoyaku:

[Her Lt. Pinkerton] was arrogant, ignorant and ill-mannered. Yet at the same time the actress herself seemed more essentially feminine than any of the other girls on stage.

This, Major Gruver instinctively understands, is what makes the Otokoyaku so popular with the women. That, although they wear men’s clothing and are aping masculine attitudes, they are understood to be even better women than the other women around them. After Gruver has fallen in love with, lived with and been forced to give up his relationship with Hana-Ogi, an Otokoyaku, he comes to truly understand and appreciate her abilities. Watching her play the same Lt. Pinkerton role he was disgusted by above, he says:

Now my reaction was different…. She had studied with intimiate care my mannerisms and now reproduced them in burlesque form. When she lit a cigarette she mimicked me, when she propositioned Madame Butterfly it was me trying to kiss her on the Bitch-bashi.

The Otokoyaku is poised, like so many drag kings, between a feminine interpretation of idealized masculinity and a lampoon of “gendered” mannerisms.

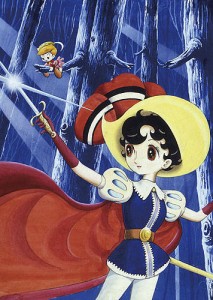

In 1954, God of Manga, Tezuka Osamu combined the Otokoyaku of Takarazuka with the hyper-feminine Snow White of Disney and created a prototype for all Girl Princes that would come later – Safire of Princess Knight/Ribon no Kishi (soon to be published in English by Vertical Publishing.) Safire was a girl, but forced for political reasons to live as a boy. Like the Otokoyaku of Takarazuka, she is an object of desire for other women, but essentially feminine. Although she falls in love with a man, she never loses her own heroic qualities. Safire set the standard very high for all Girl Princes who followed in her footsteps.

In 1954, God of Manga, Tezuka Osamu combined the Otokoyaku of Takarazuka with the hyper-feminine Snow White of Disney and created a prototype for all Girl Princes that would come later – Safire of Princess Knight/Ribon no Kishi (soon to be published in English by Vertical Publishing.) Safire was a girl, but forced for political reasons to live as a boy. Like the Otokoyaku of Takarazuka, she is an object of desire for other women, but essentially feminine. Although she falls in love with a man, she never loses her own heroic qualities. Safire set the standard very high for all Girl Princes who followed in her footsteps.

Safire is “forced” to pretend to be a boy, and she longs, in quiet moments, to wear frilly dresses and go to a dance or two, but she does not reject the privilege granted to her as a Prince. She cheerfully sets out on quests when it suits her. Safire is the hero many little girls want to be before the stories explain that they are merely meant to be the reward for the Prince. What women want, when we watch Otokoyaku, is to be wooed by a “man” who understands us (because he is a woman.) When we look at the Girl Prince, we simply want to be her.

In 1973, Ryoko Ikeda (if Tezuka is the God of manga, I’m inclined to think of Ikeda as the Goddess,) took up the challenge Tezuka had laid down with Ribon no Kishi and produced her defining work, Rose of Versailles. (Interestingly Rose of Versailles is one of the favorite productions of the Takarazuka, with countless iterations over the years since Lady Oscar made her debut in Margaret magazine. Ribon no Kishi was made into a musical theatre production, but never by Takarazuka, which is headquartered in the town where Tezuka grew up.) Lady Oscar, like Safire, was a girl raised as a boy and the story is set during the years leading up to the French Revolution – which is just as fantastic an age as the purely fantasy world in which Safire lives. Also like Safire, Oscar was attractive to other women, but her own heart was taken by her closest friend, Andre. The story comes to an end at the appropriately epic storming of the Bastille. Oscar changed the map for the Girl Prince completely. She does not wish to be girly, she is completely embedded in her Otokoyaku life, and does not reject it, even when love becomes an issue. Oscar’s difficulties accepting Andre are entirely due to their separate stations in life and, even more troublesome to the upright Oscar – the fact that she is his military superior. Gender roles or sexuality are not the issue here. Oscar imbued many of the Girl Princes after her with a fierce sense of duty and honor.

In 1978, Ikeda once again broached the concept of the Girl Prince, this time with the far more obscure manga Claudine. Claudine is notable for its ambiguity about the sexuality and/or gender identification of the lead character. It is never truly clear if Claudine is a man in a woman’s body, or a lesbian who simply desires male privilege and opportunity to love freely. Either interpretation is valid. Ikeda masterfully raises the ante on Tezuka with these two stories, setting the tone for many Girl Princes to come. Now, not only are Girl Princes likely to be attractive to their own sex, they might be attracted to other women. The Girl Prince’s role as “butch” in the relationship has been established.

In 1983, the cool, competent Otokoyaku-type character Shinokita Reiko, from Yajikita Gakuen Douchuuki owned Akita Shoten’s popularity polls for years. Otokoyaku and Girl Princes are sexiest to other women when they don men’s clothing. Kita is the perfect reluctant Otokoyaku; cold, emotionally distant, rejecting the women who want her with disdain and being even more attractive to them for being unattainable. Kita is forced by circumstances to play “host” at a Host club, a role that would forever change the perception of the Otokoyaku in Yuri Manga. “Hosts,” like hostesses, cater to the emotional needs of a club’s clientele, playing on established gender roles in Japanese society, in order to stimulate the club’s business. When Reiko dons a tux to become top host “Rei,” she merges the world of Otokoyaku and Girl Prince in a way that will never quite be separate again.

Another master of shoujo manga, Kurimoto Kaoru, took up the cause of the Girl Prince in 1986’s Paros no Ken a romantic tragedy about a Girl Prince, Erminia, who rejects the love of men, including her Andre, her knight and champion, Yurias, for the love of a serving girl, Fiona. The story changes the focus of the Girl Prince’s interests from the political to the personal. Not only does Erminia reject her fate, she leaves her kingdom to a usurper in order to find happiness with her true love.

Another master of shoujo manga, Kurimoto Kaoru, took up the cause of the Girl Prince in 1986’s Paros no Ken a romantic tragedy about a Girl Prince, Erminia, who rejects the love of men, including her Andre, her knight and champion, Yurias, for the love of a serving girl, Fiona. The story changes the focus of the Girl Prince’s interests from the political to the personal. Not only does Erminia reject her fate, she leaves her kingdom to a usurper in order to find happiness with her true love.

Which bring us to – and don’t tell me you didn’t expect this – Sailor Moon. Takeuchi Naoko embraces the Otokoyaku as host/Girl Prince role with the creation of Tenoh Haruka who, we are informed, has the heart of both a man and a woman. Like Erminia, Haruka is willing to reject her fate but it is her partner, Kaioh Michiru, who leads her to face and embrace it. Like the other Otokoyaku who had come before her in manga, Haruka looks studly in a suit, has the polished manners of a popular host and is clearly, and unrepentantly, butch. Her former life as a member of the Moon Kingdom court provides many an opportunity to imagine her as the Girl Prince, as indeed, the official art of the series frequently did. Haruka was so incredibly popular that she set the standard for Otokoyaku characters for years to come, and we can see echoes of her even to this day, in characters like Otokoyaku Izumi from Nobara no Mori no Otome-tachi.

Just before the turn of the century, the Girl Prince was reborn in Revolutionary Girl Utena (about to be re-released as remastered DVD by Nozomi Right/Stuff.) Tenjou Utena followed her predecessors by blurring gender lines, adopting boy’s clothes to create her own unique look. In Utena, the concept of masculinity takes second place to the the concept of Princeliness. Like Safire, Utena saves princesses…and princes…and redefines for herself and for the audience what “Being a Prince” means. Because the anime, the manga, the movie and the movie manga each tell slightly different versions of this story, the creators, Saito Chiho and Ikuhara Kunihiko are given the freedom to play “what if?” with Utena. What is the outcome if she loves the Prince? What if she rejects him? What if she loves her rescued Princess? What if the world itself rejects her? Each ending plays with the ideas established by Girl Princes before her and, as anyone who has seen the television anime can attest to, there is overt acknowledgement of literary roots in character and set design. Ikeda Ryouko, and Yoshiya Nobuko are both present as guardian angels in this narrative.

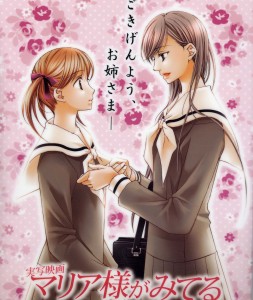

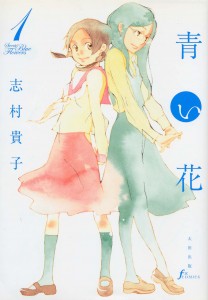

By the early 2000s, the concept of the Takarazuka Otokoyaku has not really been shed from Yuri manga – if anything it had become intrinsic. Where a character was feminine, but has “masculine” qualities – or is simply gay – they are sometimes overtly given the role of Otokoyaku. In Konno Oyuki’s Maria-sama ga Miteru, the protaganist Yumi thinks that Sei looks like a “Takarazuka Top Star” in one of the novels, confirming what we already knew – that she is butchy. And, in Takako Shimura’s Aoi Hana, it’s obvious to us that Sugimoto-sempai is destined for the role of Heathcliff in the school play version of Wuthering Heights. When it came time to create a mascot for my own Yuricon, there was no doubt in my mind that the archetype I sought for our organization was going to be the Girl Prince. Yuriko is both Otokoyaku and the Girl Prince of her own story, translated to a more modern interpretation of “Prince.” Yuriko is a pop idol. Clothes and their assigned gender roles are fluid for her, but there’s no doubt in readers’ minds that she is modern royalty.

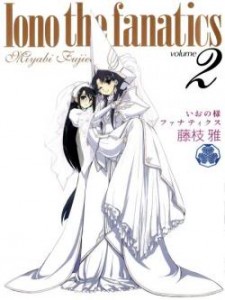

Which brings us to one of my favorite subversions of the Girl Prince role, the Queen in Fujieda Miyabi’s fantasy, comedy romance, Iono-sama Fanatics. Iono-sama is actual royalty, the Queen of some small, unnamed western kingdom. Iono-sama is both attractive to and attracted to other women, which leads to a harem story of epic and humorous proportions. A plot point in the second volume is that the various ladies-in-waiting, suffering from Iono-sama’s prolonged absence are waging an civil war. In Iono-sama’s world, royalty hath its privileges and neither gender, nor sexuality, are issues if the Queen chooses to bestow her love upon you.

Which brings us to one of my favorite subversions of the Girl Prince role, the Queen in Fujieda Miyabi’s fantasy, comedy romance, Iono-sama Fanatics. Iono-sama is actual royalty, the Queen of some small, unnamed western kingdom. Iono-sama is both attractive to and attracted to other women, which leads to a harem story of epic and humorous proportions. A plot point in the second volume is that the various ladies-in-waiting, suffering from Iono-sama’s prolonged absence are waging an civil war. In Iono-sama’s world, royalty hath its privileges and neither gender, nor sexuality, are issues if the Queen chooses to bestow her love upon you.

Whether the Girl Prince is an actual prince, a girl who wants to be a prince, a cross-dresser who is fully invested in being a woman, or is simply the boyish star of the school, as we read Yuri manga, The Girl Prince and the polished suit-wearing Otokoyaku are fixtures. The role allows us to understand and express our feminine and masculine ideals. We can play the Prince and still get the Princess for our efforts. However we approach the Girl Prince, it can’t be denied that she, and the Otokoyaku and their damn classic timeliness (as witnessed by the current reprints and re-releases) are contributors to it feeling like we’re reading the the Same Damn Story.

Postscript – this post makes 1 year here at Hooded Utilitarian. I’m still excited and pleased to be included among such luminaries in the comics crit scene. I’ll be buying myself a cake, sticking a candle in it and blowing out later today.

Aoi Hana was another mid-2000’s series that has now become an iconic series for Yuri fans, in part due to stellar writing and characterization and in part due to a not financially successful, but very beautifully made anime in 2009.

Aoi Hana was another mid-2000’s series that has now become an iconic series for Yuri fans, in part due to stellar writing and characterization and in part due to a not financially successful, but very beautifully made anime in 2009.