In honor of Holy Week, I’m republishing (with some corrections) an old review which first appeared in the pages of The Comics Journal (#261) in 2004.

For those whose memories don’t stretch that far back, Chester Brown’s Yummy Fur was one of the mainstays of the independent comics scene in the late 80s. It was in the pages of Yummy Fur that some of his most important works first appeared, among them Ed the Happy Clown, The Playboy and I Never Liked You. He has since receded into the background once again following the publication of Louis Riel in 2003.

Brown began serializing his adaptation of the Gospels in Yummy Fur #4 in 1987. The entire series has never been collected and the only way to access them is through back issues of Yummy Fur or the magic of photocopying.

***

A Review of Chester Brown’s Mark and Matthew

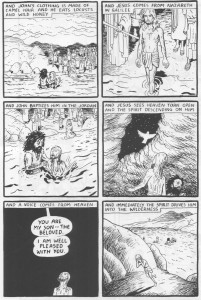

Mark

Chester Brown once explained his decision to embark on a project to adapt the Gospels in an interview at Two-Handed Man. “Certainly at the beginning, it was a matter of trying to figure out what I believed about this stuff,” he informed his interviewer, “It was a matter of trying to figure out whether I even believed the Christian claims—whether or not Jesus was divine.”

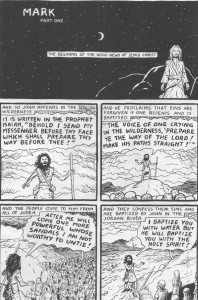

As such a modicum of restraint appears to characterize the early chapters of Mark. Brown’s adaptation seems to reveal an artist who is still struggling with both his craft and the quality of the garment through which he’s picking. One may also choose to wonder if part of the reason for this is some residual Christian guilt. Some years earlier, in a conversation with Scott Grammel in The Comics Journal #135, Brown revealed that he was probably unable to say that “Jesus wasn’t divine without worrying whether [he] would go to hell”, and this as recently as the mid-80s.

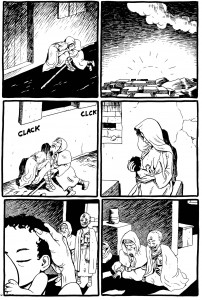

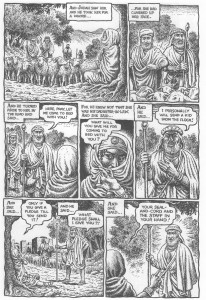

The reputation that Brown’s Gospel adaptations have for being ingeniously blasphemous is mostly based on his interpretation of Matthew. The Christ of Brown’s Mark, on the other hand, is serene and always in control. He is almost untouched by foul humanity and the rigors of life. His disciples act respectably and never display unscrupulous intent or a lack of etiquette at the dinner table. Judas, as we see him in this gospel adaptation, is neither craven nor a zealot but by all appearances merely youthful and naïve.

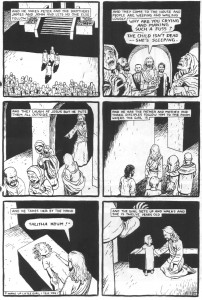

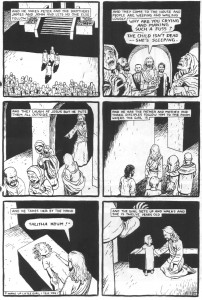

This in itself is not a criticism for Brown does achieve a degree of humanity and insight in this early adaptation, such as with the hemorrhaging woman and the widow in the story of the widow’s mite. When Jesus heals Jarius’ daughter (Mark 5: 41-42), Brown shows Jesus kneeling beside the awakened twelve year old girl with a smile on his face. All this is in keeping with the placid figure of Christ the author presents in Mark. One might say that this is the kind of Jesus that children still learn about in Sunday school.

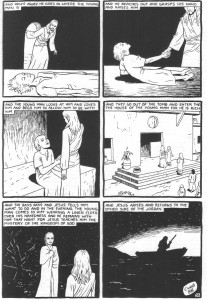

It is only in the later stages of Mark that Brown introduces his first piece of apocrypha. Derived from a letter of uncertain authenticity written by Clement of Alexandria, the so-called Secret Gospel of Mark is described by the author of the letter as a “more spiritual” gospel for the use of “those who were being perfected”, the interpretation of which would “lead the hearers into the innermost sanctuary of truth hidden by seven veils” (it can be perused on-line here):

In this “gospel”, Jesus raises the brother of a woman in Bethany. It continues:

“But the youth, looking upon him, loved him and began to beseech him that he might be with him. And going out of the tomb they came into the house of the youth, for he was rich. And after six days Jesus told him what to do and in the evening the youth comes to him, wearing a linen cloth over his naked body. And he remained with him that night, for Jesus taught him the mystery of the Kingdom of God. And thence, arising, he returned to the other side of the Jordan.”

It is often remarked that this passage bears comparison not only with the story of Lazarus but also Mark 14:51-52 where another unidentified young man wearing nothing but a linen sheet is found. This excerpt is dealt with at length in the pages of “The Fur Bag” (the letter column of Yummy Fur) in Yummy Fur #14 by letter writer Rob Walton and Brown himself. Here the baptism of special initiates and the homosexual undertones of the “secret gospel” are brought forth as well as the possible gullibility and motivations of Clement (if the document is in fact genuine).

Brown has indicated that he owes a debt to Morton Smith’s The Secret Gospel and Jesus the Magician for stirring him to revisit the Gospels. The former tome recounts Smith’s discovery of the aforementioned letter fragment. The latter book emphasizes Jesus’ position as a miracle worker and attempts to explain the manner in which some non-believers viewed Christ. It is a firmly critical and speculative text which cast the Gospels in the light of apology, unscrupulous “theological motives” and propaganda in addition to your basic lies and half-truths. With respect to the scribal view on Jesus, Smith writes: “his background and baptism prove him an ordinary man and a sinner, therefore, the miracles, success, impious behavior, and supernatural claims prove him a magician” (an appellation which Smith explains at length in his book). Smith also suggests a few qualities which he feels separated Jesus from other miracle workers and exorcists of the times, and which led to his being labeled a magician: “compulsive behavior, neglect of the Law and claims to supernatural status”. Some of these traits are highlighted in Brown’s Gospel adaptations, most notably in Matthew.

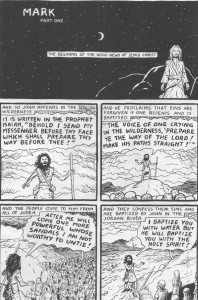

Even so, Brown’s Mark does not read like the work of someone who is challenging received wisdom but an exercise in illustration. One panel in the first part of his adaptation stands out and is at odds with the rest of the otherwise flat narration. On page 2, Jesus is shown being driven into the wilderness (Mark 1:12), his hands clasped to his eyes in translation of the word “driveth” which is said to be the same word used for Jesus’ expulsion of demons.

Another panel of interpretative interest (and one which departs somewhat from tradition) occurs in Mark 6:20 where Herod is shown listening eagerly to John outside his jail cell.

Brown only begins to bring a more creative and personal hand to his adaptation when Jesus enters Gennesaret. Here a number of the villagers are depicted (somewhat amusingly) with faces inscribed with stupefaction, while others look sternly and suspiciously out of their houses. For once, the sick and the infirm look weak, desperate and, occasionally, uncouth; something previously addressed only in relation to the Gadarene (or, in Brown’s version, Gerasene) demoniac. From this point forward, the crowd scenes become increasingly adept and Jesus begins to show a wider range of emotions – most notably anger but also a certain irritability. He begins to carry an almost threatening air and Brown slowly begins to distance himself from the previous depictions of tender righteousness.

Apart from these aesthetic considerations, there are also some unusual choices in Brown’s otherwise unadventurous transcription of Mark. When Jesus encounters a leper in Mark 1:41, he is said to be moved by compassion and not “anger” (as stated in Brown’s narration). Jesus, as depicted in the panel in question, seems at best to be irritated and one feels that Brown has over interpreted the stern warning given to the leper not to tell anyone of his healing, charging the episode with something more than what is suggested in the original text.

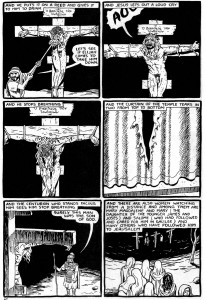

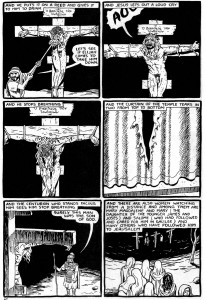

In such instances, we see Brown approaching Mark in the spirit of a student and not as a person who has fully immersed himself in the subject matter. He shows occasional delight (particularly in his notes) when he chances upon what he perceives to be deadly “mistakes” in the text of Mark. In the notes for Mark 5:1, for example, he brings up the dispute concerning Jesus’s journey across the sea of Galilee to Gerasa (a translation which occurs in the NIV, NASB and RSV but not the KJV which translates as the country of the Gadarenes). Brown points out that the town of Gesara is “a good 30 miles south-east of that sea while other non-secular commentaries have also pointed out that Origen identified Gesara as an Arabian city “which has neither sea nor lake near it”. It is an age old and complicated dispute which involves varying manuscripts and the possible misidentification of the village of Khersa. All of which has little place here. Suffice it to say, Brown reserves this kind of textural criticism for his notes, his adaptation of Mark generally being free from such gloating or any study of the unity or disunity of the gospels. For instance, he obscures Jesus’ final cry in the closing moments of his crucifixion as the exact nature of this exclamation is not stated in the Gospel of Mark. Further, the mention of two demoniacs in Matthew but not in Mark is not resolved, explained or questioned.

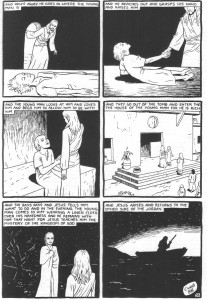

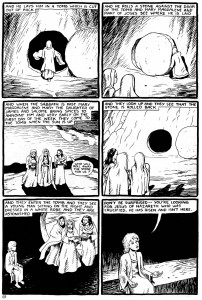

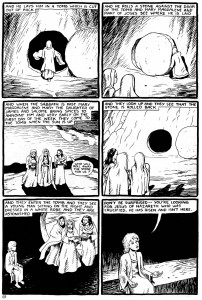

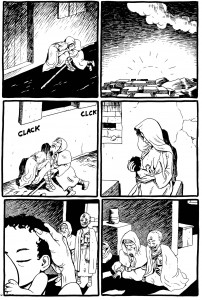

At times, Brown’s idiosyncratic choices hamper the sense of the text. In his notes to Mark 10:35 to 12:27, for example, Brown indicates that he has left the crowds out of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem because Mark does not specify them. Such a literal approach has limitations and is occasionally counter-productive and counter-intuitive. At one point, Joseph of Arimathea is shown closing Jesus’ tomb by himself and with his bare hands, while the panel which follows this (describing Mark 16:1-4) makes a nonsense of that depiction:

“And when the sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, had bought sweet spices, that they might come and anoint him. And very early in the morning the first day of the week, they came unto the sepulchre at the rising of the sun. And they said among themselves, Who shall roll us away the stone from the door of the sepulchre? And when they looked, they saw that the stone was rolled away: for it was very great.” [emphasis mine]

The sense of the passage is embedded in Mark and it might have been more instructive if Brown had brought into play the fact that Joseph was a rich man. With this in mind, one would have expected a number of servants to have helped him remove Jesus from the cross and to prepare and transfer the corpse for burial.

Brown has explained his somewhat flat interpretation of Mark in his interview in The Comics Journal #135:

“People were expecting me to do something weird with Mark. And I am doing all the Gospels…And so starting from a traditional view seemed like a good place to start. And I can get weirder as I go along but…”

And later:

“ But what I was doing was trying to distance the reader. Because I’m going to tell it over another three times. The feeling was ‘I can draw in closer in Matthew, Luke, and whatever. This is your beginning point, just kind of show the reader what’s there, don’t get him in too close.’ And looking over it I’m not too pleased with how it looks because I think I got in even closer than I wanted to. If I was doing it again I would distance the reader even more, I think.”

The resultant comic will be of variable interest to the reader as a consequence of this decision.

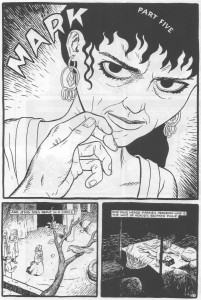

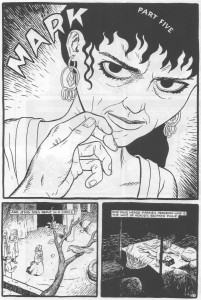

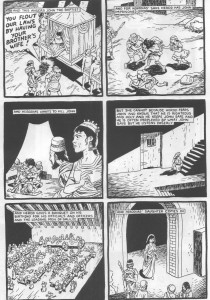

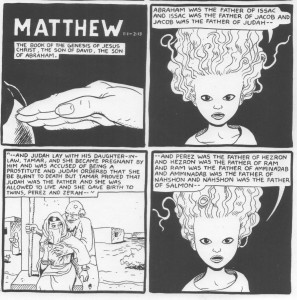

Matthew

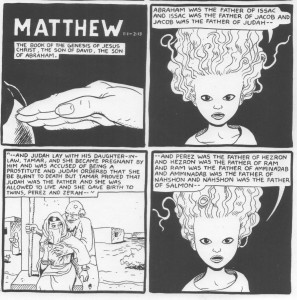

Brown’s adaptation of Matthew harbors more vitality than his work on Mark. It is also possessed of a more divisive purpose. He signals his new intentions right from the start in his exposition on the genealogy found at the beginning of Matthew. Here Brown elaborates on the story found in Genesis chapter 38 (which concerns the sordid tale of Judah and his daughter-in-law, Tamar).

[Robert Crumb’s take on the same subject for comparison]

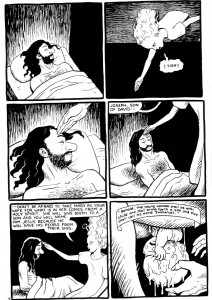

This is followed by his depictions of Rahab (a Canaanite woman and a harlot), Ruth (a Moabite woman who is asked by her mother-in-law, Naomi, to sexually entrap her kinsman, Boaz) and Bathsheba (an adulteress whose history is well known). Traditional interpretations have suggested that the willful inclusion of these women on the part of the author of Matthew presents a confrontation of the androcentric interpretation of Israel’s history, a desire to strengthen the earthly origins of the Christ and a means of characterizing a new attitude towards foreigners and outsiders following the passion and resurrection. However, Brown’s citation of Jane Schaberg’s The Illegitimacy of Jesus appears to indicate that he feels that the “mention of these four women is designed to lead Matthew’s reader to expect another, final story of a woman who becomes a social misfit in some way; is wronged or thwarted; who is party to a sexual act that places her in great danger; and whose story has an outcome that repairs the social fabric and ensures the birth of a child who is legitimate or legitimated” (Schaberg). Schaberg argues the case for a strong tradition of Jesus’ illegitimacy (as opposed to his virginal conception), suggesting that the key verses in Matthew such as Matthew 1:20 (“Joseph, thou son of David, fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife: for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost”) should be taken in a figurative and not a literal manner, in essence adopting the increasing fashionable rejection of a literal virgin birth. Morton Smith (whom, you will remember, Brown admires) also mentions the genealogy in Jesus the Magician where he suggests that “Matthew wanted to excuse Mary by these implied analogies”.

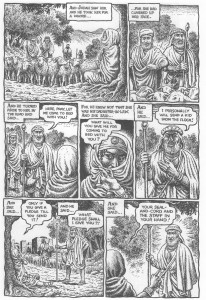

One may choose to differ with many of Brown’s choices in Matthew but these choices are, in general, more interesting than those in Mark. For instance, Brown’s decision to depict the magi as “poor wandering holy [men]” while not thoroughly convincing, feels correct in spirit. His point that the costly gifts “are often considered to be an indicator that the magi were rich but…they aren’t necessarily so” is a weak one but it allows for a certain tension in the scenes showing the traveling magi.

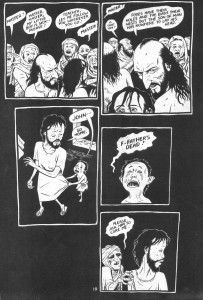

In his interpretation of Matthew 8:21-22 (“And another of his disciples said unto him, Lord, suffer me first to go and bury my father. But Jesus said unto him, Follow me; and let the dead bury their dead.”) he forsakes the unvarnished and doggedly literal readings he administered in Mark. Instead he chooses a well known but more creative reading where the father is seen to be Zebedee and the disciple, John. In so doing, he appears to take into account the use of the word, “disciple”, which was given to a select few and Matthew 20:20 which contains the phrase “the mother of Zebedee’s children” which suggests that Zebedee was no longer alive.

The notes which accompany Matthew, on the other hand, are seldom profitable. For example, in his depiction of the holy family’s return from Egypt, Brown reproduces Matthew’s quotation of Jeremiah writing, “In Ramah was there a voice heard, lamentation and weeping and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children and would not be comforted because they are not.” In his notes, he innocently wonders if “Matthew [is] saying that the king’s men, who were supposed to kill the baby boy’s in Bethlehem, got mixed up and killed the baby boys in Ramah by mistake?” It is a query which seems obtuse since commentary is widely available on the passage. One traditional viewpoint indicates that the prophecy was fulfilled during the Babylonian captivity in which Nebuzaradan conquered Jerusalem and assembled and disposed of the captives at Rama. The quotation is seen to be used in poetic comparison. There are other more involved commentaries on Matthew’s use of this verse, all of which are far more complex than Brown suggests in his notes. Seen in this light, Brown’s remark does nothing for the reader’s confidence in his research at this early stage in his career.

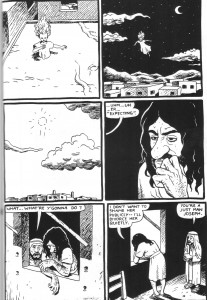

Brown follows this by recounting Joseph’s rejection of Judea (which was ruled by the tyrannical Archelaus, Herod’s successor and son) in favor of Galilee (which was governed by Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great and Malthace). The Bible passage reads as follows:

“When Herod died, an angel of the Lord suddenly appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt and said, ‘Get up, take the child and his mother, and go to the land of Israel, for those who were seeking the child’s life are dead.’ Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother, and went to the land of Israel. But when he heard that Archelaus was ruling over Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there. And after being warned in a dream, he went away to the district of Galilee.” (Matthew 2: 19-22, NRSV)

Brown depicts Joseph fleeing back to his wife who is shown lying beneath a tree in a desolate landscape. In his “Notes on Matthew”, Brown cannot resist a snide aside and suggests that “the angel was apparently unaware that Galilee was also at this time ruled by one of Herod’s sons — Herod Antipas”. This somewhat sloppy comment highlights the spontaneous nature of Brown’s notes. They rarely suggest the wealth of commentary which feeds off the texts of the Gospels. There is, for example, the more well-disposed and Christian viewpoint by Adam Clarke (in his commentaries from 1810-1825). He states concerning the move to Galilee:

“Here Antipas governed, who is allowed to have been of a comparatively mild disposition; and, being intent on building two cities, Julias and Tiberias, he endeavored, by a mild carriage and promises of considerable immunities, to entice people from other provinces to come and settle in them. He was besides in a state of enmity with his brother Archelaus: this was a most favorable circumstance to the holy family; and though God did not permit them to go to any of the new cities, yet they dwelt in peace, safety, and comfort at Nazareth.”

This is but one viewpoint among many, and it is a particularly old and traditional one. Suffice to say, there is an atmosphere of carelessness in Brown’s notes which suggest that they should be thoroughly revised in any reprint or dispensed with altogether.

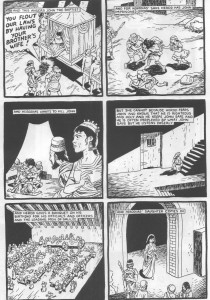

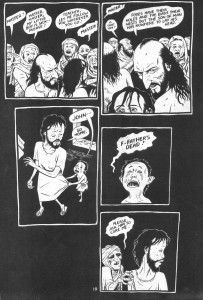

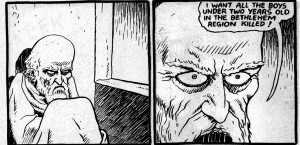

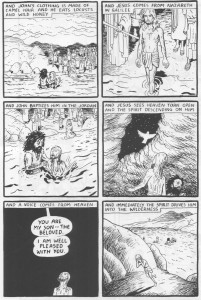

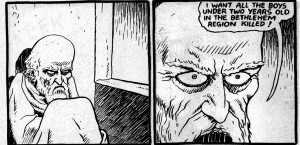

Between Brown’s adaptations of Mark and Matthew, there occurs a change in authorial temperament and viewpoint. There is a more radicalized disbelief and a greater focus on the fleshy and earthly aspects of the story. This is most evident in Brown’s conception of biblical figures. The hardened Christ of Brown’s Matthew is in marked contrast to the Jesus of Mark who, for all intents and purposes, could have taken a step out from a kindergarten school painting – smartly berobed, well coiffured and immaculate. In Matthew, We no longer see this calm aspect of Christ but the scowling features once used to depict the jealous Pharisees in his adaptation of Mark. There is also the figure of Herod the Great who is now depicted as a man on the edge of violence, driven to extremes by his unyielding character and a chronic, incurable disease. He is the man we picture when Josephus writes, “A man he was of great barbarity toward all men equally, and a slave to his passions, but above the consideration of what was right”.

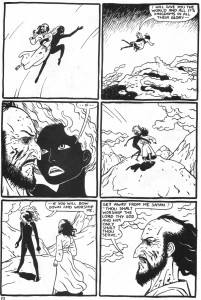

Satan who once appeared as an angel in white raiment in Mark has been transformed into a thin, ebony-hued youth with pallid lips and hair.

John is no longer the rugged but respectable prophet but a wizened, decrepit mad man screaming in his cell. Like Jesus himself, he has become sharp featured, aggressive and utterly determined; a screaming, scabby looking creature tripping on the borders of sanity. In his illustration of Matthew 3:7-8, we are not given the traditional “O generation of vipers, who hath warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bring forth therefore fruits meet for repentance”, but rather, “You fucking vipers! Do you really expect me to baptize you in the Jordan?! You could at least try to look repentant!!”

Jesus’ disciples are acne-ridden, surly, ill-bred louts. They pick their noses and eat their snot, mimicking the cartoonist’s own proclivities. They are possessed of unrestrained gluttony, feel up women as a matter of course, and are callous and rude to their relatives when asked for assistance. In other instances, there is the hint of cunning managerial skills as they selfishly protect their restricted communion with Jesus.

Brown’s approach emphasizes the poverty and crudeness of the people who once inhabited Palestine. We are allowed to see a diverse set of motivations as well as the naked selfishness and cruelty of a series of non-entities. He is like a latter-day Pasolini, rejecting purity in favor of an honest depiction of men and women. In an interview with Steve Solomos (Crash #1), Brown, insists that the snot-eating was not included for “shock value”:

“Solomos: There will be a perception that you’re doing it for some nominal level of shock value…Do you feel that you’re including it for that reason?

Brown: No. When I was growing up, it always seemed to me that what I wanted to do when I became an artist, was to show life the way I thought it really was.”

Here we see an echo of the writings of Celsus the Platonist, author of “The True Discourse” (the original being lost, it was reconstructed from the refutation written by Origen, Against Celsus) who describes the disciples as “tax collectors and sailors of the worst sort, not even able to read or write, with whom he ran, as a fugitive, from one place to another, making his living shamefully as a beggar”. This passage is cited in Smith’s Jesus the Magician and dismissed as “typical ancient polemic [which] may have come from any opponent…though the picture may be correct”. It is a tradition which continues today in the form of studies of the historical Jesus.

In accordance with his desire to bridge the distance created in Mark, Brown dispenses with the narrator’s voice thus allowing the plot and dialogue to flow more naturally. The conversations in Matthew are no longer paraphrased at length and in respectful tones but are shortened and contemporized – transformed into quasi-modern sentences, short exclamations and guttural snaps. Here we find the influence of Andy Gaus’ The Unvarnished Gospels (one of the translations which Brown says he used) which is noted for its literal translation of the gospels which eschews much theological baggage. The Sermon on the Mount is similarly altered to a form which best fits Brown’s appreciation of Jesus’ recorded words. Jesus is shown in close-up for nearly seven pages and Brown strays perilously close to the kind of boring conception which he accuses Scorsese of in his remarks on the film adaptation of The Last Temptation of Christ (in TCJ #135). This sequence may be compared with Brown’s flat handling of Jesus’ parables in his adaptation of Mark and comes across as tedious and uninspired, the familiar stories and words floundering on bland imagination.

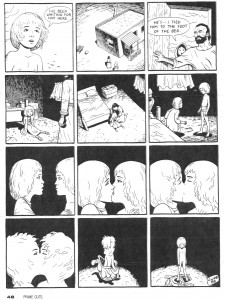

In his portrayal of Matthew 4:23 to 5:10 (which includes the Sermon on the Mount), Brown, for once, chooses to expand upon and dramatize the gospels by means of a digression concerning a mother and her two daughters. The mother is blind and disfigured, and the younger daughter, a coarse and sickly individual. They form part of Brown’s recreation of the reality and texture of the times, his vision of what the author of Matthew suggests when he writes, “all sick people that were taken with divers diseases and torments, and those which were possessed with devils, and those which were lunatick, and those that had the palsy; and he healed them.”

Amidst all this harsh reality, Brown remains strangely faithful to the text where more rigidly secular and atheistic authors would defer less. The healing of a leper is presented as miracle rather than myth. The centurion’s servant is similarly raised without disagreement or question. In response to Scott Grammel’s (TCJ #135) query concerning this seemingly unquestioning acceptance of the gospel stories, Brown answers:

“Well, I’m adapting the Gospel, and…That’s what it says in the Gospel. It says he drove a demon out, so why not show it?”

Such jarring turns and discrepancies in presentation result in a certain inconsistency of tone. What one detects on a reading of Matthew is not a man struggling with a neglected text or his spirituality but an artist who has allowed his occasional whims to supersede any general thrust or plan. This leads to the narratively unremarkable and somewhat juvenile tenor of Jesus’ healing of the two blind men where one blind man, upon being healed, says to the other, “Hey man, you’re really ugly.” In another instance, when one of John the Baptist’s disciples informs his master that his jailer has kept the wild honey (to be taken with the Baptist’s locust) for himself, John replies, “Bastard.” These episodes suggest an attempt at humor in the vein of Monty Python’s Life of Brian which seems out of place in an adaptation which is for the most part quite serious.

Brown’s view of reality permeates his adaptation of Matthew. As he has stated in relation to autobiography in his interview in Crash:

“…if you just concentrate on telling whatever story you’re telling that’s fine, but any given story can be told in a number of ways. If you expand your parameters, for instance, you’re not just telling your story, you’re also talking about life, about how you see the world around you.”

Pertinent to this view are Brown’s views on Gnosticism which he explains in TCJ #135:

“I’ve called myself a gnostic, but I’m not really sure I fit into the…The part that appeals to me is that you accept yourself as the true authority on God. You don’t rely on outside sources. You don’t rely on your preacher. You don’t rely on the Bible or anything. You just say, ‘What is my opinion? What in me tells me about God, about the world?’”

In The Gnostic Gospels, Elaine Pagels describes these individuals as follows: “Like circles of artists today, gnostics considered original creative invention to be the mark of anyone who becomes spiritually alive…Whoever merely repeated his teacher’s words was considered immature….Most offensive, from [Irenaeus’] point of view, is that they admit that nothing supports their writings except their own intuition. When challenged, “‘they either mention mere human feelings, or else refer to the harmony that can be seen in creation’”.

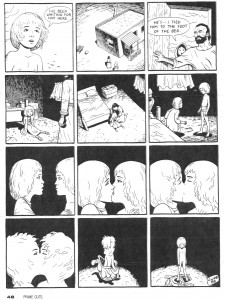

Brown has adapted this approach for both sacred and profane purposes. What has been “revealed” to him not only includes his interpretation of the Gospel message but also the altogether worldly emotions and mannerisms of the biblical characters; a modern day twist on the gnostic tradition of continuing revelation which is not hindered by direct experience. Needless to say, Brown’s irreverence does not match the spirituality displayed by the gnostic texts but he once displayed some interest in them as evidenced by his adaptation of a portion of the 61st chapter of Pistis Sophia for Prime Cuts #3 (1987). In the story, Mary relates an event from Jesus’ childhood in which she encounters the Spirit which she mistakes for a demon or “a phantom to tempt me”. She binds the Spirit to a bed and goes out in search of Joseph and Jesus. The family returns to their house where the Spirit is released and becomes one with Mary’s son upon kissing him. Brown’s extract is told without elaboration or embellishment and the reader is left to search for the mystical interpretation of the passage in the rest of Pistis Sophia.

The world of Matthew, on the other hand is fueled less by numinous revelation than by the fluctuating moods of the artist. In his interview at Two-Handed Man, Brown reiterated what has always been a variable interest in the project: “…I don’t think I’m going to be getting to Luke or John. But you never know. My interest in Swedenborg might get me wanting to do Luke or John now.” Matthew feels more like a diary of the artist’s feelings which range from a sudden interest in the text which is then periodically overtaken by boredom resulting in a lack of inspiration. A meticulously crafted plan is rarely in evidence. A somewhat haphazard method of working (in relation to that period) is described by Brown in The Comics Journal #135:

“When I have something really plotted out, really planned, by the time I’m half-way through a story I’m bored with it, and I want to do something different. Often I’ll have a specific plan – ‘Yeah, I know where I’m going with a story’ – and then half-way through I say, ‘No, I don’t want to do that. Let’s take off in this direction and do this instead.’ To some degree just to keep myself interested in the work.”

But what worked to a certain extent (when played to its limit) for the surrealistic tales from Yummy Fur, founders and fails in these Gospel adaptations if only because of undue moderation. Further, while the reader is frequently invigorated by Brown’s skillful use of comics narrative, the sharpness of his perceptions is often wanting. This is highlighted by any number of famous or more recent literary comparisons. Brown, himself, claims to dislike Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ for its style of writing (TCJ #135; “I just couldn’t get into the writing, and gave up after a couple of pages”) but had he persisted, he would have witnessed a highly charged and ostensibly heretical faith generating a novel told with uncommon passion and intensity. Jim Crace’s Quarantine (a novel which post-dates Brown’s adaptations and which is concerned with the mythical and human aspects of the Christian faith) creates a microcosm of the narratives and teachings of the New Testament through the device of Jesus’ forty days in the desert. Bruce Mutard’s Abba (from the SPX 2002 anthology) is a fine example of intellectual rigor and creativity in conceptualizing the Gospels in comics form. More pertinent, as far as Brown’s desire to inject humor into his story is concerned, is Mikhail Bulgakov’s amiably sacrilegious The Master and Magarita which has such a keen insight into the politics and philosophy of the passion story that one’s imagination is immediately seized.

Brown’s poorly-thought out blasphemy, on the other hand, is often quite unimaginative, and there are few things less needful than dull blasphemy. The extensive back catalogue of novels or redactions concerning Jesus and the gospels (and there are very many others by D. H. Lawrence, Norman Mailer, José Saramago et al.) present themselves as models for what has been accomplished with the basic text of the Gospels. It behooves any serious author to educate themselves as to what has been achieved that they may identify what is aesthetically and intellectually profitable in further explorations of the text. This is something which Brown has patently failed to do in his adaptations.

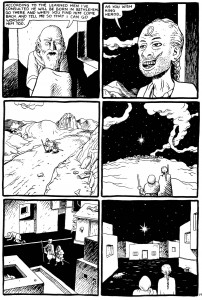

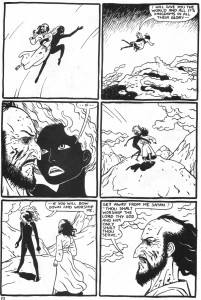

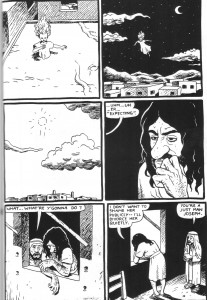

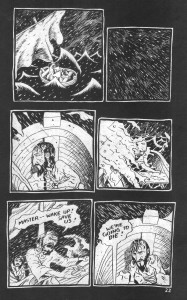

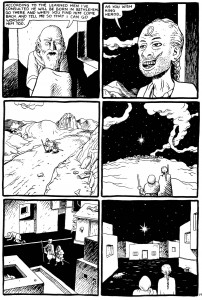

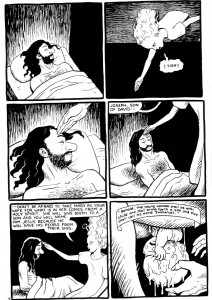

Still, Brown’s Matthew is not without its own, quite insular pleasures. At the outset of his adaptation, there is a fairly delightful and quite unbiblical panel in which an angel adorned in loose robes is seen diving down through the heavens with some pyramids in the background.

The gentle wafting of this heavenly being through earthly abodes and then into Joseph’s dream is done with wonderful rhythmic delicacy.

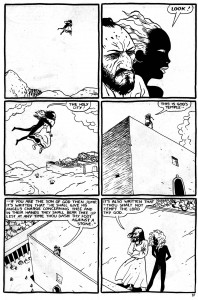

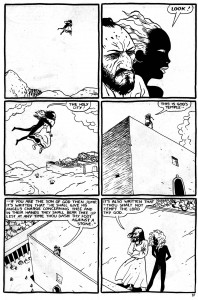

When Satan carries Jesus through the air to the top of the temple there is an unmistakable feeling of lightness and elegance.

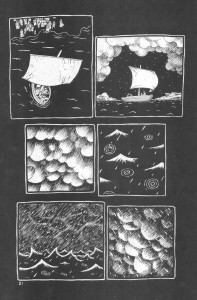

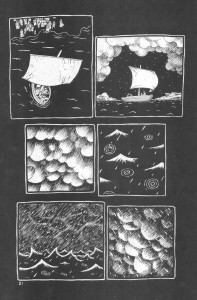

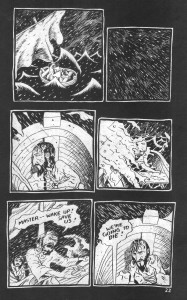

At periodic intervals in the story, we see the familiar motif of minute individuals fleeing across sparse landscapes; a dispassionate “God’s-eye” view used with even greater frequency by Brown in Louis Riel. The calming of the storm from Matthew 8:24 is illustrated with a care unseen in Mark. Here the elements are transformed into symbols and the short passage elevated to the level of a mythical quest or journey.

It is a far cry from the poorly drawn waves and boats in Part 3 of Mark where the sequence of panels showing Jesus stilling the waves seem particularly rushed and poorly thought out.

Nevertheless, Brown’s Gospel adaptations remain exploratory devices with a very selfish purpose. They may have worked as journeys of discovery for the author but they fail when assessed as fully formed works of art. Excessive restraint, a lack of coherence and a paucity of invention dampens both adaptations. What we are left with are snapshots of the state of mind of the artist resulting in an ephemeral experience lacking intellectual weight.