I recently visited my grandmother in Iowa. Now over ninety years old, her and my grandfather have finally moved out of their home of thirty years and into a transitional assisted care facility. Part apartment complex, part hotel and part hospital, the center provides a kind of gradated care, simply preparing meals and cleaning house for some residence, with more substantial help for others.

Before heading down for breakfast, I visited with my grandmother in her room and looked over some of her watercolors, which were hanging on the walls of her living space. Talking about her painting led to a brief discussion about technique, which in turn led her to voice the very familiar argument that art is something that can’t be taught, is in fact something inherent in someone. When I pointed out that she herself had learned from a teacher of some skill, she modified the statement somewhat, essentially saying that there was some kind of spark that could not be acquired like some techniques might be, and that it was this spark that was missing from most art.

She warmed to the topic over our breakfast of rice crispies and room temperature eggs. “It’s magic that there’s not enough of,” she said and then gestured to the room around us. “Take whoever designed this place.” I looked around at the off-white room, saw the bland color, the plastic trim, the perfunctory decoration, complete with obligatory fake oil painting landscapes and little plastic flowers. “This place was designed by an architect.” She said the word with a disapproving shake of her head. “We need less architects, and more magicians.”

Instead of debating it any further, we ate our eggs and drank our watery grapefruit juice and moved on to other activities. But the division she suggested—and her judgment on the room where we ate—stuck with me for the rest of the day.

There’s something to that idea, I thought. But she has it exactly backwards.

She’s right in the sense that many, many things in our world are needlessly, almost willfully, functional alone, when there’s no compelling reason for them to be so. The room we sat in was oppressively dreary, oppressively utilitarian, with nothing but the most casual thought given to the look of the space itself. It doesn’t cost any more to build a beautiful, functional room than it does to build a dreary functional one. Similarly, a plate of eggs cost the same regardless of what temperature they’ve been served at, or whether or not they’ve been seasoned with a little bit of salt, onions, some paprika, and a hint of vinegar. I would indeed consider the eggs that my sweetheart is capable of making a kind of magic, especially when compared to what we shoveled in our mouths that morning.

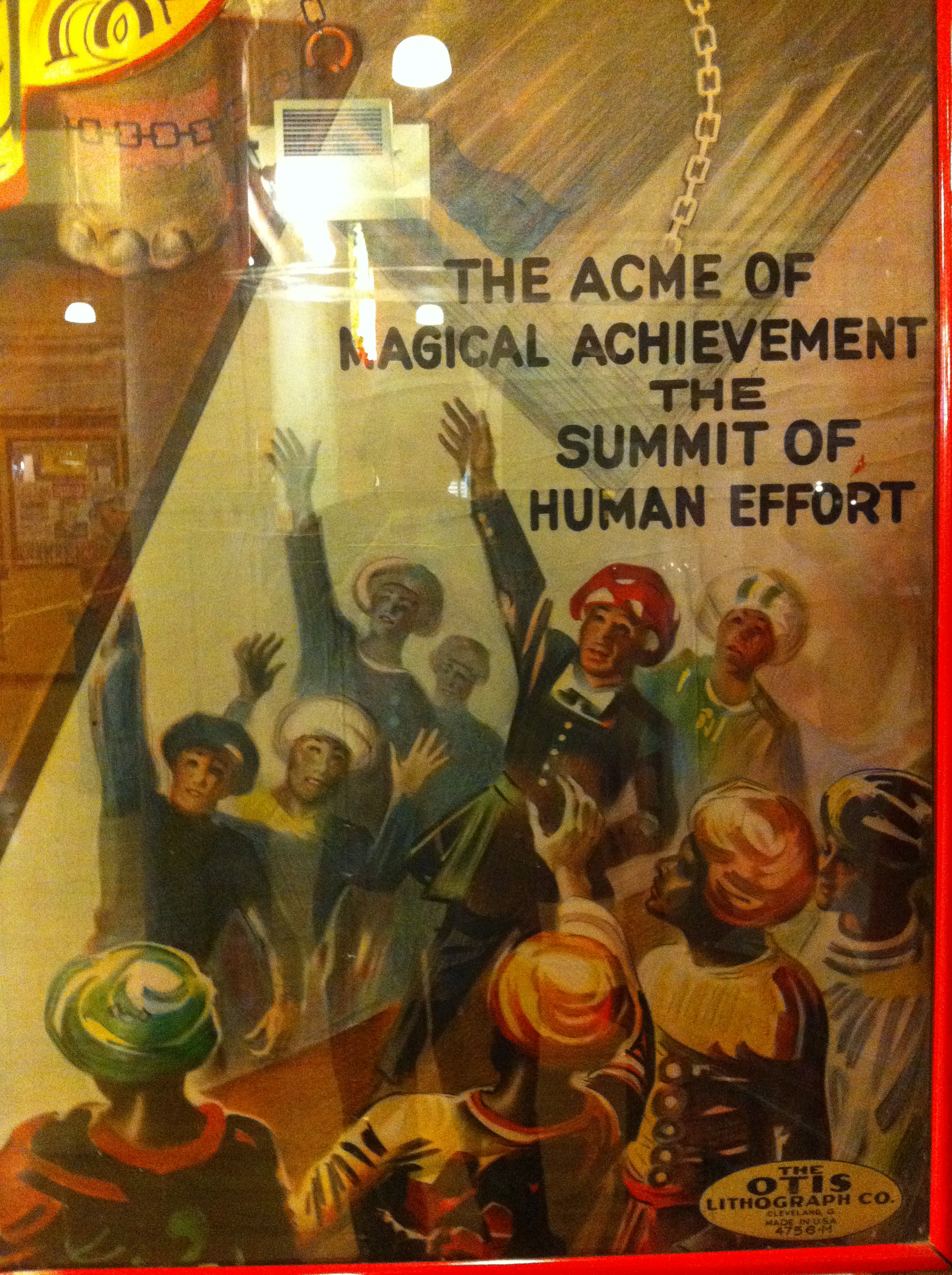

But there are two things that significantly undercut the argument for magic, and the magician, or at least the magic metaphor. First, as you might have heard, magic is all about illusion, is in fact only presentation. A good magician is literally a presenter, a salesman, his creation content-less save the verve of his presentation alone. It’s a bit like non-representational painting in a way—when the subject of painting has been removed completely, the attributes of art themselves are the content, and these attributes themselves must be compelling for the painting to be successful by itself.

Secondly, the illusion of magic is, like any other technical skill, eminently teachable. Want to learn sleight-of-hand? It’ll take reading a page of directions, practicing in front of a mirror for a few hours, and more time to hone your patter. Of course, there’s aptitudes involved, and even physical limitations—dexterity, verbal skill, etc, and some magicians with only rudimentary technical skills will at the very beginning have a more convincing act than other magicians with a wider range of technical skill. But the basic skills themselves are accessible to almost anyone.

Compare this to the architect who designed the room in which we ate that dreary breakfast. Though the man may have lacked a certain surface charm or presentation to his work, his task was ultimately much more difficult than the task of virtually any fine artist. Specifically, his work had to be functional, in specific, demonstrable ways. The template that the room was most likely adapted from had to literally hold up the weight of the ceiling, had to protect the inhabitants from fire and earthquake and flooding, had to be open and spacious, had to freely circulate air, had to be easily cleanable, had to be built primarily with affordable materials and readily available modular parts.

What visual artists are ever tasked with so many requirements? Only designers of various stripes will ever have to deal with so many potentially competing requirements for their work, and certainly they will never have to deal with such heavy consequences to failure. An incompetently designed poster is unreadable, doesn’t impart information clearly, or at worst drives its potential audience away from the product it endorses. An incompetently designed building can mean discomfort or death.

In certain divisions of both North American comics and popular music there is a mistrust of the crafted, of the purposeful, a search for the authentic that manifests in a variety of ways. A comic might tell us of its authenticity by gritty subject matter that challenges some kind of conventions or taste, or by an appeal to truthfulness, or actuality (most common in autobiographical comics or even semi-memoir). Or it might manifest itself in a visual crudity, which is its own kind of claim to the authentic. Even more common is the appeal that reaches beyond the art itself, into the biography of the artist.

There is, in short, an overabundance of preciousness in much of the arts world. I can’t say that this is a recent trend, or even what may have caused it—but I can point to the anonymous nature of much of the great art of previous centuries, and the cult of celebrity that has sprung up to embrace the artist in recent history. Regardless of the cause, there’s no doubt in my mind that preciousness actively works against the ruthlessness necessary to create art as an architect—to create with a high level of function and intention. In my time teaching songwriting, it was one of my chief pieces of advice to novices—if you really want to improve, write about something you don’t care about at all. It’s harder to be ruthless, to acknowledge when something just isn’t functioning the way it was intended, when its something you feel strongly about emotionally. The same is just as true for a cartoonist—self-expression is a fine goal if a comic is literally intended only for one’s self, but the moment it has an audience other than the creator of the work, the function has radically changed.

On the other side of this divide lies the ultimate expression of the architect’s art alone, no magic and only function—pornography, romance novels, the action movie. Stripped of any artistry, or magic, these categories exist with clear functions, clear outcomes in mind. Did her heart race? Did he come? My grandmother would possibly find the comparison between her dining room and Pool Studs 4 less than useful, but for me the metaphor holds, and brings the argument back to her side of the divide. How much more interesting would a piece of pornography be if it were carried out with the artistry, with the presentation and verve, of a Melville or a Pynchon? What would a romance novel look like that violated that strict, stultifying formula, that dared interject a kind of artistry into the romantic recipe? What would an action movie look like that had all of the skill of its competitors, but had equal parts message and purpose, and even guts?

I recently re-watched Bridge on the River Kwai, David Lean’s 1957 Hollywood classic, and while it’s far from a perfect movie, it does an incredible job balancing these seemingly competing objectives. Here is a movie that performs its functions very well—it causes the heart to race, it builds tension and expectation over a tremendous amount of time and satisfies those expectations in surprising ways, and it does all of this while managing to say something larger in a meaningful and unique way, even indicting the audience’s expectations by violating them. Even more effective than Kwai are virtually any Kurosawa movie from the 1950’s, all of which were the Japanese equivalent of blockbuster genre movies, popular entertainments, that manage to each say something unique and important within that framework.

As we discuss the marginalized status of comics in contemporary culture, and the increasingly fragmented nature of the music and film industries, it’s worth thinking about this divide, and why and how it might be bridged. In the case of comics, the split is self-evident—genre comics that attempt something measurable, racing the pulse or inciting a sense of wonder, and incompetently pursue these goals without any spark of artistry or originality—or comics in which the spark is the point itself, yet often lack a functional, craft-centric grounding.

And maybe this is an argument for art makers versus art consumers—to be willing to be less precious, more ruthless with yourself and your work, or conversely, to be willing to suspend that ruthlessness at key times, letting intuition guide certain decisions.

For my taste, both as consumer and creator, I prefer work that is capable of straddling that divide, that is well-crafted, intentional, and simultaneously has that streak of verve and originality that comes across as magic. Planning, laying the groundwork, but willing to detour, to deviate when some impulse hits us, or something new seems on the horizon. Why shouldn’t we expect a little architecture with our magic?

“Not that far from paradise…”

“Not that far from paradise…”

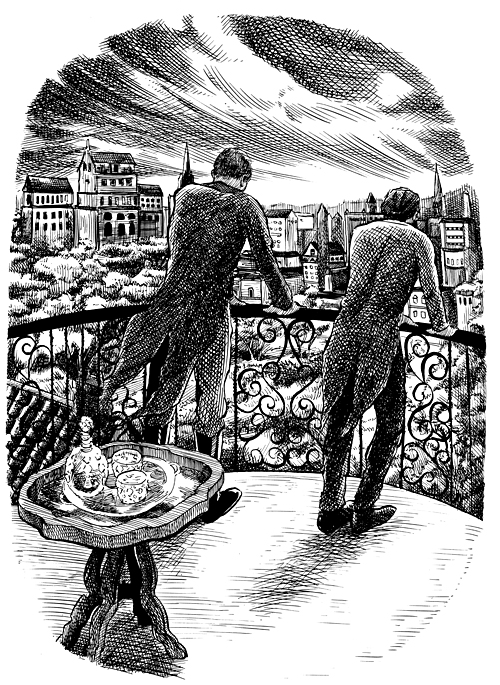

“An unintentional peek inside the process—a paste-up Mizuki head atop a photo-referenced body.”

“An unintentional peek inside the process—a paste-up Mizuki head atop a photo-referenced body.”