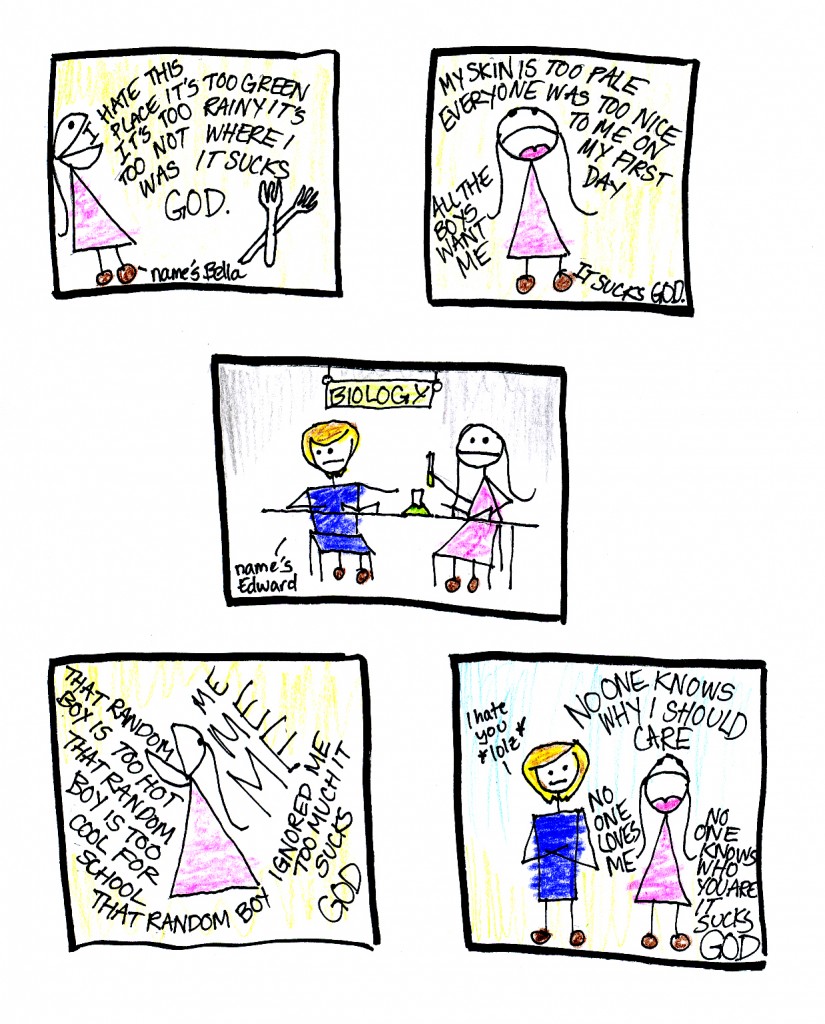

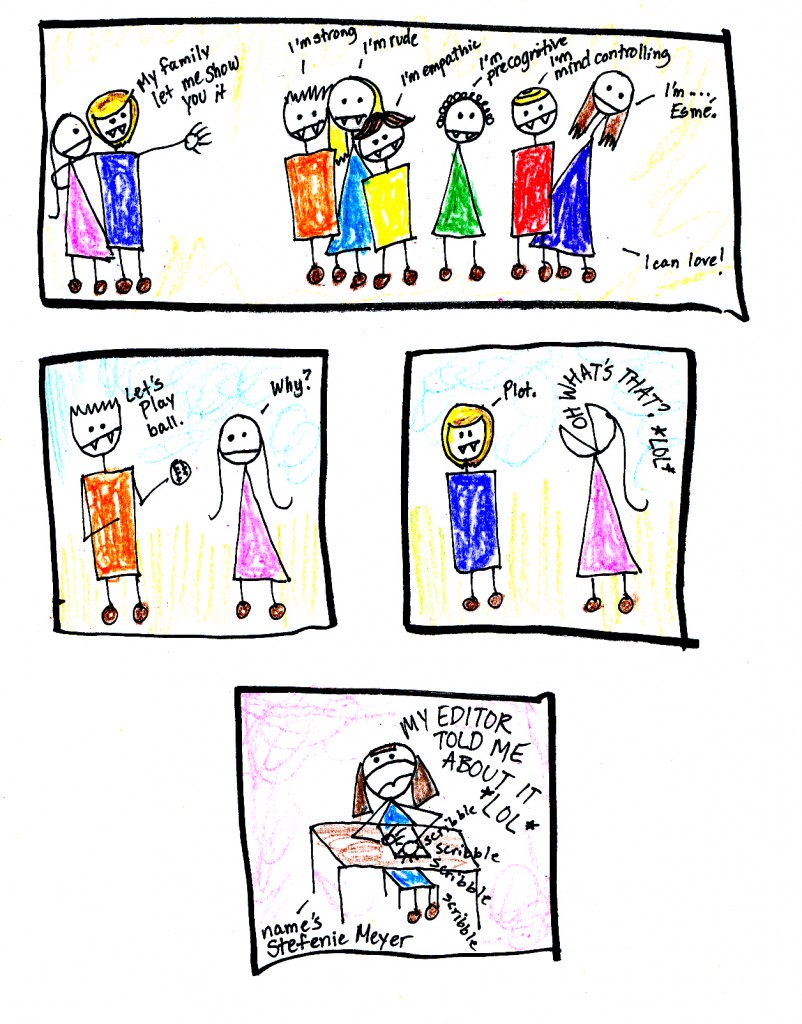

I had an article on the Atlantic a couple of days ago in which I talked about the Hunger Games and Twilight, comparing Bella and Katniss. I argue that Bella is in many ways stereotypically feminine (passive, focused on romance and motherhood) while Katniss is in many ways stereotypically masculine (competent, deadly, not focused on romance).

People have not been pleased with me. Specifically, Alyssa Rosenberg and Amber Taylor take me to task. Alyssa started out by calling me condescending and went on to say:

First, there’s something really profoundly weird and limited about this definition of femininity — and condescending in the piece’s sense that a totalizing devotion to motherhood, to relationships, to sex, to girliness is the only, or most worthy, definition of femininity. The second-wave feminists who produced Our Bodies, Ourselves may not have done the research into a groundbreaking medical text that changed the relationship between women and the medical establishment while wearing pretty dresses*, but that doesn’t mean that their work wasn’t deeply attuned to the feminine. Creating space for women’s voices in hip-hop, and suggesting that women have something specific to offer the form, may not be explicitly attuned to the state of romantic and sexual relationships, but that doesn’t mean it’s not an exploration and assertion of the feminine. Choosing to have a baby even if it means you have to be on bed rest or endanger your life might mean you’re devoted to motherhood, but it doesn’t actually make you more of a woman than casting off your cloak to duel the holy hell out of Bellatrix Lestrange or climbing into an exo-suit and doing battle for a little girl’s life — and by extension, the continued existence of the human race.

As is usually the case, Caroline Small is more eloquent than I am, so I’ll let her respond. This is a comment she left on the Atlantic site before Alyssa’s post went up, but I think it resonates.

The comments to this article are really pretty interesting. But pretty disheartening, really, too. A lot of popular feminism, which seems to be where some of the commenters are coming from, isn’t very attentive to the history of cultural gendering, where certain traits were indeed gendered “female” and certain “male”, and where the male traits were generally considered better and more worthwhile. Those preferences haven’t really gone away — the sets of traits and behaviors are still valued differently. They’re just more available to individual people of both genders now.

I’ve been seeing these “I’m glad I grew up with Buffy and not Bella” things too, so it’s not just Katniss. I sympathize; Bella doesn’t particularly appeal to me either. But it doesn’t take much insight to recognize that she aligns more closely with “traditional femininity” than Buffy and Katniss do.

Fortunately, there are lots of women today whose self-perception aligns with the masculine values, to the point that those women would never describe those traits as “masculine”. I think these comments reflect that. But being able to see them as non-gendered, or differently gendered, is something we have the luxury of doing because we were fortunate enough to have come up after feminism fought those hard battles, in an era where other people and society overall enforce those gendered norms on our individual bodies much, much less.

A lot of people seem to think that the point of feminism is making “masculine” behavior acceptable for women — or making no behavior unacceptable for women, that is, separating the behavior from the bodies of the people who perform the behavior and not judging women who prefer those historically masculine traits. And I agree that is one goal of feminism.

But feminism used to also be about recognizing the value and beauty of the way women historically did things, of women’s ways of knowing, of women’s unique experiences — of “femininity” as a counterweight to the excesses of “masculine” strength and authority and aggression. It used to be about valuing “femininity” as a place from which we could criticize and challenge the bad things in our world. A lot of the distaste for Bella is genuine distaste for the historically “feminine” categories and behaviors and values and aesthetics, but it’s generally expressed without even the slightest recognition of how problematic and limiting — and historically patriarchal — that attitude is.

So I’m hesitant that it’s a good thing to derogate traditional femininity, either in favor of traditional masculinity or even in favor of an individual woman’s right to behave however she pleases. A feminism that rejects the very notion that culture is gendered (in ways that have nothing to do with biology) is a feminism that’s amputated its best critique of power. It’s essentially co-opted by historically masculine cultural biases and preferences — including the ones for violence and strength. That’s tragic, if that’s where we are.

Part of the appeal of characters like Katniss is that they challenge conventional gender without completely eradicating it. Part of the appeal of characters like Bella is that they subvert conventional gender without really challenging it at all. I don’t much like either of them at a personal “do I want to hang out with these people” level — I’m with the person who prefers Hermione, although HP is almost as badly written as Twilight. But it strikes me that not being able — or willing — to think the difference is a problem.

Girl power is great — except when it moves beyond allowing people with female bodies to behave any way they like and becomes a new set of restrictive, normative, angry, prejudiced norms that bully people with female bodies into behaving a certain way. The widespread and almost-always knee-jerk “feminist” contempt for Bella, both in itself and in comparison with “tough” female characters like Katniss and Buffy, is a tremendous intellectual and social failure in that respect.

So I think it’s worth asking the defenders of Katniss — is there actually a feminist critique of the power structure that gets Katniss into the book’s defining life or death challenge, the kind of systematic feminist critique you get from, say, Joanna Russ or Erica Jong? I can be talked out of this position, but it doesn’t seem to me that there is. The same question could be asked of Buffy, and of any other girl power heroine. Twilight may actually have the edge on that one — there is a definite critique of the Volturi from Bella’s perspective that aligns nicely, yes, with Christian ideals, but also with traditionally feminine ones. (Although Bella is certainly no Alyx.)

Ignoring the seductiveness of those “masculine” characteristics, pretending their relationship to authority and strength and power and violence is transformed just because a woman engages in them — — that’s not feminist at all. And neither is perpetuating biases and prejudices against the historically gendered-feminine traits. A feminism that can’t make room for Bella is a feminism that’s going to have a lot of trouble getting purchase with women who like Bella, and that seems like a tremendous mistake to me.

To me it seems like Caroline has Alyssa pretty much dead to rights. Alyssa is basically insisting that the feminine be defined as, “anything that women do.” And that has been one goal of feminism. But another goal has been to champion those things traditionally associated with women. And you can’t champion those things if you feel it’s condescending to even suggest that they exist.

The difficulty with championing them if you refuse to admit they exist is perhaps best epitomized by another commenter on the Atlantic. This is Genevieve du Lac. Her comment has garnered 16 likes, so I don’t think she’s just speaking for herself here.

I’m really disgusted with these definitions of femininity and feminism. Why can’t a woman be competent and feminine at the same time? Femininity is not weak. And Bella is just retarded. The two neurons she’s got floating around in her cerebellum are drunk off too much estrogen… like most 16 year olds. So she’s got some feminine qualities – like following her feelings, etc. That does not make her the epitome of femininity.

I’d like to think a woman can be feminine and still be competent. I can wear my makeup and heels and take care of my hair just as well as I sky dive, shoot an arrow, shoot a pistol, finish my MBA, and have a career. Sheesh.

Like Alyssa, Genevieve wants the feminine to mean everything women do. But to get there, she has to call Bella “retarded” and sneer at her “estrogen.” Which, to me, seems like a problem.

Alyssa doesn’t lambast Bella in such offensive terms, of course, which I appreciate. But she is coming from at least a vaguely similar line of country.

And while those values are worth examining further, Twilight‘s also eminently critiqueable on narrative grounds, something Noah gives very little credence. Complexity is the stuff of genuinely compelling decision-making, as well as compelling storytelling. What’s troubling about Twilight is less the idea that Bella picks Edward and more the inevitability of their eventual union. Once Edward walks into Bella’s science class, she never really considers anything else, never gets presented with any other truly compelling options, she treats the humans in her life who are graduating and going off to their own adventures with dismissiveness and disinterest. Tough choices are fascinating. Defending the world’s kindest fate is rather dull.

And just as I’m bored by Bella’s certainty and dismissive attitudes towards people who set other priorities and take other paths, I don’t appreciate the idea that I don’t live up to Noah Berlatsky’s very particular standards of femininity, I’m doing it wrong. There may be effective arguments for a Christian focus on love rather than strength. But a strident and myopic lecture to women with a variety of priorities isn’t likely to be one of them.

Alyssa is arguing for narrative complexity — complexity involving action, politics, and suspense. She goes on to argue that the Hunger Games is interesting in part because it’s about how politics destroys families; how the public trumps the private and why that’s evil.

But…that’s not unique to the Hunger Games. It’s just how adventure stories work. You’re fighting for home and family; that’s the motivation, but it’s not the story. That’s why Amber Taylor is misleading when she says that Katniss’ actions are all about her family. Diagetically they are…but that isn’t what the books focus on. We hardly know Katniss’ sister, or her relationship to her; Pru really just exists as a kind of pure idol of goodness and innocence, a reason to keep fighting, like any number of pure-women-left-at-home in any number of adventure books. What Alyssa wants, and what adventure narratives want, isn’t the exploration of love and relationships…so they push those over to the side. And instead, you get violence and things blowing up.

I don’t have any problem with things blowing up in my entertainment. I don’t know that I seek that kind of thing out quite as much as my wife does, but I’m perfectly happy to go along for the ride. Enjoyable as those things-blowing-up are, though, I like other kinds of stories too. Such as, occasionally, romance. Which is what Twilight is.

As in most romances, narrative complexity, in terms of events and suspense, is not the point. You know Bella is going to get her guy, just like you know that Jane Austen’s heroines are going to end up happily married. That’s how romance works. People — often people known as “women” — read those books not because they’re idiots who don’t like complexity, but because they are interested in a different kind of complexity. Specifically, they’re interested in the ins and outs of love; not just whether people love each other, but how they do so; not who will live and who will die, but what will they say and how will they say it and how will their relationship develop?

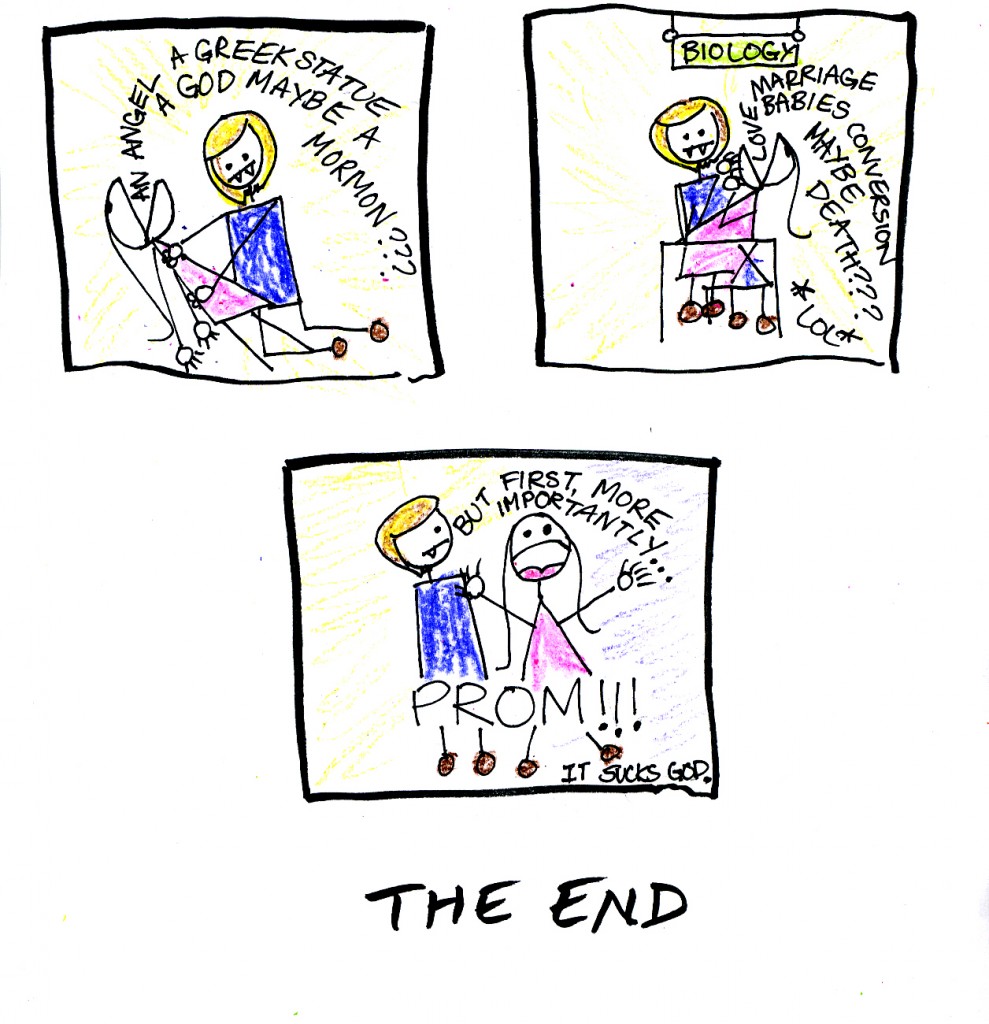

For instance, there’s that scene in the Twilight series where Edward’s family is voting on whether to turn Bella into a vampire. Edward’s father votes yes, and his reason is that Edward has vowed to kill himself when Bella dies. For Edward’s father, his love for his son therefore means that Bella has to also live forever.

As a father, as a husband, as someone who has been thinking a lot recently about in-laws and what they mean for marriage and for love — I found, and find that scene really moving. And that’s where the suspense and surprise in Twilight comes from; from the explanation and exploration of love and intimacy, not just between Bella and Edward, but between Bella and Jacob, and Jacob and Edward, and Edward’s family — the entire cast of characters, in other words. It’s different than watching the nifty new way Katniss kills somebody, I’ll grant you. But it’s not worse. For me, anyway, I find it more compelling. Or, as Laura Blackwood says in a lovely recent essay, “The Twilight series challenges what I would call the “Buffy Summers Maxim”: that teen heroines be physically empowered, oftentimes at the expense of emotional clarity.”

None of which means that Katniss, or Alyssa, is “doing it wrong.” Even if the Hunger Games is (like Twilight) dreadfully written, I still like Katniss. I like watching her figure out how to kill people; I like her tomboyish competence; I like her butchness, I like her delight in dressing up, even if the series won’t really allow her to own it. I like the way she finds true love and family at the end. She’s not my favorite heroine in the world, and her whining (like Bella’s) gets pretty tedious, but overall, I enjoyed spending time with her. That’s why I went out of my way to say at the end of my essay at the Atlantic that Katniss and Bella aren’t opposed. As another writer notes here, it’s not an either/or choice. Lots of girls admire both characters. I think it’s possible to imagine that Twilight’s heroine and the Hunger Games’ heroine would find something in each other to love and admire as well.

Amber Taylor disagrees with me there, though:

The idea that there would be a fight is absurd, but the reason for peace is not that Bella and Katniss “might understand each other’s desires and each other’s strength” and walk away in mutual respect. Katniss wouldn’t fight Bella because Bella is not an autocratic totalitarian dictator. Bella threatens exactly nothing that Katniss values, and thus Katniss, a user of violence who is not inherently violent, would probably shrug. Katniss’s political consciousness and promotion of self-rule does not threaten Bella’s tiny microverse of loved ones and would likewise be a non-issue to Bella.

For Taylor, Katniss wouldn’t respect Bella. She’d just ignore her, because Bella is no threat. But I have to ask…if Bella “threatens exactly nothing” that Katniss or Taylor or Alyssa values, why then are so many writers so eager to attack her? If she’s not a danger, why call her a “retard” or deride her as dull or passive or sneer at her “tiny microverse of loved ones” — that thing that some of us of insufficient political consciousness refer to as our “family”? What, in other words, is so scary about Bella and the girls who love her? And could it, maybe, have something to do with our culture’s ambivalence about femininity?

I’ll let Sarah Blackwood have the last word.

Bella holds up a cracked mirror and shows us some things we don’t want to see. But she also reminds us that the imagination resists checklists of appropriate behavior. Teen girls resist checklists. The really interesting conversations start to happen when we stop circling the wagons against “bad examples” and “passivity” and start exploring not only what we want our heroines to be like, but why.