In case anyone is trying to download any of my mixes, mediafire appears to have deleted them all for unclear reasons. Not sure why yet.

Monthly Archives: September 2009

A Nostalgia for Racism?

A few months ago, I chanced upon a piece of art which was up for sale at one of Russ Cochran’s on-line comic art auctions. It was a Hal Foster drawn Tarzan Sunday which is usually an event in original art collecting because of the rarity of such samples.

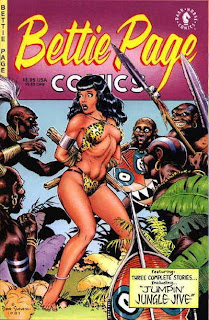

As you can see, it is a fairly reasonable example of Foster’s art on Tarzan. It was, however, a no-go area for me whatever my feelings for Foster’s artistry. The reasons are simple: this piece of art would not have given me any pleasure and I would have been embarrassed to put it on display in my apartment. I simply don’t have the blindness or nostalgia for racism which allows for an enjoyment of this kind of art. There’s the Aryan beauty standing before the squat depravity that is the Cannibal Chief and later the rather simian qualities of the cannibal tribe as they howl for blood. I have as little passion for the subject matter as I would a depiction of bestiality. There are many pit holes in collecting original art but this particular aspect is less often highlighted. After all, wouldn’t most comic art collectors salivate over the original art to this Frazetta-drawn cover…

…with its razor-toothed natives within an inch of pawing at the white female’s succulent breasts? Any objections would be easily dismissed with the notion that these were more gentle and less enlightened times where such stereotypes were the norm. And clearly they were. The fact that the art displays beautiful draftsmanship and is historically important ensures that such aspects are easily brushed under the carpet. A collector friend of mine who finds such images unpleasant was less happy with this easy acceptance which obviates concerns for subject matter. He placed a comment on this Frazetta cover (when it was displayed on Comic Art Fans) comparing it to Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s depiction of Storm Saxon in V for Vendetta.

As many readers will know, there is a whole area of collecting known as Jungle Girl art of which one of the prime examples must be this particular piece by Dave Stevens:

It’s all in good fun, both mocking homage and parody. It would seem churlish by some to find these items in any way offensive. There are of course people who collect “coon” art for historical purposes (which is absolutely valid) and others because it gives them pleasure. I don’t find the latter aspect particularly respectable.

Another story in the same vein which I chanced upon recently is “Yellow Heat” by Bruce Jones and Russ Heath from Vampirella #58 (Mar. 1977) the scans of which can be found here). The entire story was sold at a Heritage auction for $4370 in 2002

The story is one of Jones’ best remembered from Vampirella in part because of Heath’s lovely hyper-realistic art but mostly because of its twist ending. [I would suggest that those unfamiliar with “Yellow Heat” read the story before continuing with this article.] You’ll find two appreciations of “Yellow Heat” here and here. The Comics Journal message board regular Mike Hunter describes the effect as such:

“Bruce Jones and Russ Heath wreaking havoc with our “we humans are all alike, after all” expectations in “Yellow Heat”.”

Jones uses a number of tricks of sleight of hand to achieve the shock ending in this story. Part of the justification for the ending would appear to lie in the first page where a sort of incipient famine and breakdown in society is described. Jones’ script in the first panel would however suggest that the famine has not arrived and that these are much more bountiful times. The Masai warriors don’t look malnourished in the least which lessens the impact of this early description and any expectations of its relevance. There is also the description of the captive lady as a “beauty” and Heath’s great depiction of the same which effectively throws off the reader.

The confluence of a familiar coming of age story mixed with an unexpected twisting of facts and sensibilities is also a factor. These issues would be further heightened for readers familiarizing themselves with this story for the first time in the 21st century. With a greater appreciation for distant cultures, many readers would be cognizant of the fact that the Masai do not practice cannibalism and would not expect such a denouement. Others would realize that such accusations of cannibalism were often used by white colonialist as an excuse for their excesses thus eliminating such a possibility from their minds. Nor would the modern day reader (or one during the 70s I suspect) expect any writer to produce such blatantly racist caricatures of Africans in the final two panels. Readers perusing a Warren magazine in the 70s would probably be familiar with the elevated ideals of the EC line where stories like “Judgment Day” saw publication. Few readers would expect a backward looking ethos and this makes the ending that much more surprising. Perhaps it might be a useful exercise for readers to imagine a gentle story about Jews taking care of orphaned children during the Black Death before eating them in the story’s final panel. Children aren’t as delectable as beautiful African women but you get what I mean.

While I haven’t read any interviews with Campbell or Heath concerning the genesis of “Yellow Heat”, my suspicion is that there must be some explanation for the strange sensibility on display here. The story was, after all, created during the 70s and not the early 20th century when popular art was considerably less informed. It is entirely possible that “Yellow Heat” was created out of naiveté and plain wrong-headedness but it is also possible that it was born of a flippant underground sensibility – a remark on the excesses of the past (though it has to be said, nothing in the story even suggest this). In many ways, it is much more educational to read these stories “blind” than to rely on any form of stated authorial intent.

There are better examples of these kinds of cultural jibes from more recent times like Robert Crumb’s “When the Niggers Take Over America!” which is so hysterical in its excesses, all but the most simple-minded would mistake it for anything but satire.

There’s also the notable example of Chaland’s An African Adventure where every form of jungle imbued racism is brought forth.

There are the malevolent natives…

….and there’s this scene where a tribesman is slapped:

It should be clear to most readers that the only person taking a slap here is Hergé and Tintin in the Congo.

On the other hand, it would appear to many readers that Jones, Heath and Foster were drawing from the same well with respect to their imagery – the corpulent chief and malicious cannibals in both Tarzan and “Yellow Heat” being the prime examples. On a purely textural basis, Jones and Heath’s story is truly ambiguous in its racial sensitivity. Is “Yellow Heat” actually quite factual (this seems impossible), the product of a more enlightened age where having fun with racial stereotypes is perfectly acceptable (perhaps a satire; I’m sure certain African Americans would find it harmless enough) or is it symptomatic of something much less wholesome?

Face Down In The Mainstream: Batwoman

Batwoman Reborn: Batwoman in Detective Comics; 854 August 2009 (Part One of Three)

Greg Rucka ,writer

J H Williams III, art

This….This is art.

Beautiful, interesting, compelling art.

I picked this comic up because I heard it featured Batwoman, lesbian socialite by day and crime fighter at night, and I figured that I couldn’t go too far wrong there.

The story isn’t that exciting, so far, but I don’t really care. The art is absolutely exquisite. *flails hands around*

The plot is pretty much this: Batwoman is trying to find the person who is leading this religion of crime in Gotham. They’re organized by covens, and sometime in the past they caught her and tried to kill her. The leader is coming into town, and Batwoman plans to be there. Dun dun dun. Or whatever. I don’t even care.

The episode starts with a lovely little fight slash victim interrogation. Just look at this page:

The top panel is especially nice. The body torsion is correct and the leg is right, unlike my last foray into current comics, and the pose works well with the page as a whole. There’s kind of a weird, bat shaped panel thing going on, which is clever, but which I liked rather than hated. The comic takes some odd approaches to panels in general, but I very much like the way the artist moves into and out of the frames, zooming and then pulling back, choosing key bits—like her hand—to focus on.

What I like about this page is the movement. It goes from frenetic, chaotic, to quiet, wham, focus on her hand and his face, and the whole mood changes.

The comic deals with both sides of Batwoman’s identity. Her crime fighter night life, as above, and her daytime self. This is a page where she’s talking to Pop (her father I assume, but haven’t really read far enough to know for certain).

There are several fascinating things about it. One, she’s wearing crummy sweats that make her butt look big. This is not an attractive outfit; it’s the kind of thing a real woman would wear to workout in, though, if she was at home. It’s intimate and real; showing a different and fallible, human, breakable side of her.

The colors are all of a piece in the home scenes: her bright red hair fits in with the rest of the landscape of skin, wood floors and warm walls, sunlight. Very alive.

It’s quite a contrast to the fight scenes where she looks like a fetish dom.

There’s a heavy sexual element to this comic, and so far I’m finding it both sexy and well done, rather than skanky (unlike, say, Amazing Spiderman, which I picked up and would have stomped on except then I would have had to buy it). The villain—but maybe I should talk about the villain next week. No, I’m sorry, I cannot resist talking about her now:

Look at this villain! What a fantastic and fun artistic contrast. The previous pages (which I have resisted scanning, but only barely) often focus on Batwoman’s dark red lips. The villain also has painted lips. And a fetish outfit. White and innocent, very frilly and girly compared to Batwoman’s butch femme dom outfit. The boots, too, are a contrast. These boots are white and tightly laced; Batwoman’s boots are red red red with a bat in the sole.

The villain is a beautiful foil for Batwoman. When they fight—Ah, but that is a tale for next week.

In short, I thoroughly enjoyed this comic and I do not care that it was 3.99 and I do not mind the ads or the weird and badly drawn extra or the fact that I had to drive someplace special to get it. I only hope I can talk lots and lots of you into reading it and discussing it with me. My only real complaint was some truly random bolding in the dialog. Nobody would have emphasized those words in speech, but that’s kind of a quibble.

Sailor Moon

The manga Sailor Moon is the series that demonstrated, once and for all, that American girls will read about super-heroes with great enthusiasm. It features a young-looking aggressively typical school girl named Bunny. But then, one day, Bunny meets a talking cat, who turns her into… a super-hero Princess! With long hair! Nifty jewelr! Lots of deferential friends, and a handsome, dashing, mysterious true love! And, of course, she gets to keep the talking cat.

Needless to say, this abject wish fulfillment went over quite well with the target demographic; Sailor Moon manga and anime were huge in Japan, and were one of the early big manga successes in the U.S. as well. Thanks to its influence, Marvel and DC quickly leaped at the chance to reach the heretofore untapped female audience. Marvel released a Spider Girl title where the protagonist improbably turns out to be a Princess and seeks for magical jewels with companions like Grasshopper Girl and Ladybug Girl, while DC devoted its entire Minx line to sugary SF adventures in the Sailor Moon vein.

Or, you know, possibly it didn’t happen quite that way. But be that as it may…as somebody whose been incessantly blogging about at least one female super-hero, I’ve been thinking that I should read Sailor Moon for awhile. I finally managed to get to it this week, and….

Well, I wish I could say that I liked it. Obviously, it’s not intended for middle-aged guys, so my disapprobation isn’t all that surprising. Still, just because something is aimed at teen girls doesn’t mean I’ll hate it. I appreciated the naked wish fulfillment in Twilight. I adore the sugary glop that is contemporary R&B. I even enjoyed, with reservations, the manga series Cardcaptor Sakura, which is a fairly naked Sailor Moon rip-off.

Sailor Moon itself though, or at least the three volumes I managed to get through, is just not very good. In the first place, Naoko Tekeuchi’s art just doesn’t do a whole lot for me. It’s not horrible, or anything…the drawing is certainly more consistent than is often the case in American comics, and while the cartoony stylization can be a little cloying, it’s at least done professionally. Her pages, though, can get really cluttered and messy.

Clamp’s work for Cardcaptor Sakura, as a comparison, is a lot better.

As with Sailor Moon, Clamp breaks panel borders and works with different size images all jammed into one space. But they balance that by not using extraneous background detail; by using lovely, controlled patterns (the tree branches with blossoms are especially nice), and by using the panel breaks to move you thorough the story (you follow the girl’s body down to oversized legs and into the next panel of the narrative.) It’s just much more deftly done; the difference between artists with an aesthetic sense and one without.

The wriitng in Sailor Moon is similarly muddled. Bunny, or Sailor Moon, couldn’t be a much more generic or less interesting character. She’s really more a collection of traits than a person; we learn she likes video games and sleeping, that she’s terrible at school, and that she whines a lot…but cutely (at least in theory.) Her personality, as such, never takes shape beyond these not-especially-appealing tidbits — and, moreover, even these vague delineations are quickly abandoned. By the third volume, we learn that Bunny is actually Princess Serenity reincarnated (or something), and her returning memories more or less obliterate the Bunny we (barely) knew. This would be, perhaps, an improvement, except that Serenity’s only character trait seems to be mooning after her crush object, Prince Endymion.

As for the narrative itself…it’s really less a plot than a series of disconnected cliches, drawn about equally from video games and mid-drawer fantasy. There’s an eldritch evil, there’s a crystal that needs to be protected, there’s an ever escalating series of helpful sailor scouts who must be awakened, each with their own sailor power; there are battles which inevitably end in victory…etc. etc. etc. There’s some vaguely kinky mind-control too, but it’s hard to much care as fractured scene after fractured scene rushes by. Is Endymion in thrall to the evil overlord forever? I’ll never find out, since I can’t stand to read the fourth volume…but, still, I’m guessing not.

So yeah; not good — though it could be worse, certainly. There are certainly appealing moments; the gratuitously cute totem cat, for example, is in fact cute. Sailor Moon’s battle cry (“On behalf of the moon, you’re punished!”) is charmingly corny; the sort of thing you could imagine a little girl actually yelling in battle. And, though the plot is an incoherent mess, it’s a welcoming, open incoherent mess. American super-hero comics are often involuted and incomprehensible because they draw on a mass of useless continuity trivia that’s (A) stupid and (B) of no interest to anyone who hasn’t read American super-hero comics for the last twenty years. Sailor Moon, on the other hand, makes no sense not because it’s insular, but because it’s so extraneous. Sailor Moon has no background…even from volume to volume, anyone can pretty much start anywhere on any page and you’ll be as at home as you would be anywhere else. You’ve got cute girls fighting evil; you’ve got crushes; you’ve got nifty special effects; you’ve got cute cat; you’ve got gratuitous wish fulfillment. That’s it. There’s really nothing else going on — not character, not plot, not themes, nothing. In some sense, I wonder if that’s part of the reason for the series’ success. If you’re a girl, it might be easy to imagine yourself as Sailor Moon, since Sailor Moon is barely there. It might be easy to imagine your own adventures, since the adventures on offer barely exist either.

Sailor Moon gets the pander right, and given that, additional specificity might well get in the way. The books, in short, remind me a little of McDonald’s — they aren’t good in the usual sense, but you have to admire the way they identify a need and fill it with maximum efficiency and minimal frills.

Comics in the Park

As a parent, I spend a fair bit of time in parks talking to other parents while we all rather desperately try to ignore our offspring. These conversations often start out with “so what do you do when you are not herding rugrats?” And, since at least one of the things I do is write about comics, I sometimes end up talking to strangers about funnybooks.

I had two such conversations this week, both of which were pretty entertaining. The first was with a woman from Columbia, who’d also spent some time living in Mexico. She told me that Wonder Woman in Spanish is “Mujer Maravilla”, which is pretty great. She was also interested to know what I thought of the Hernandez Bros. — she said she had trouble reading their stuff because she found it so sad (I think she was talking particularly about the Palomar books.) Maybe most interesting, she told me that there was hardly any native comics industry in Columbia. Instead, what comics there were were all Spanish translations of American super-hero comics. When I asked her if there were any imported Spanish-language comics from Mexico, she said, emphatically, no — which surprised me.

The second conversation was with an English documentary filmmaker; we’ll call him D. D. had once been very interested in comics, but hadn’t followed them in a long time. He explained that when he was a kid in London, he used to buy 2000 A.D. regularly, often shopping at the great London sci-fi and comics store Forbidden Planet. Anyway, one day when he was 13 or so, D. was in the store when a couple his age walked in. The girl was stunning; D said he looked at her and knew that this was it; a girl like this was what he wanted out of life.

Meanwhile, the guy who actually was with the girl walked over to a wall of comics, spread his arms, and said, half-joking-but-not-really, “Here it is! This is my life.” D. was watching the girl’s face while her boyfriend made this declaration — and that was it. D. walked out of the comics store and never went back.

Bound to Blog: Wonder Woman #17

Marston and Peter’s Wonder Woman 16 may have been the best of the run so far, both in terms of the unusually ominous story and the adventurous art. #17 starts out well, with a marvelous cover.

Peter uses almost all of his favorite tricks here: the bison is out of scale, so WW looks almost like a doll, and even the horse seems bizarrely tiny. The motion lines are incredibly dynamic…in part because the circle is split up, I think. He also uses some of his scribbly linework for the bison’s breath…and that little cue cartoony squirrel is hard to resist. Plus, it looks like we’re going to get WW in the wild west, which sounds like it has potential. The last time travel episode, with evolving gorillas and dinosaurs and Steve turning into a cave man, was pretty great, so I was optimistic that a second might work as well.

Unfortunately, after that cover, the issue itself is pretty much…eh. Part of the problem is that the entire plot is built around a scientist Lana, her love for the no-good Carl, and WW and the Holiday girls’ efforts to cure her of same. Lana’s confusion is such that it causes her to whip up time winds which cause all and sundry to fall back into the past and relive former lives in roman and colonial times…but even such full-bore nuttiness can’t disguise the fact that this is a pretty staid man-done-her-wrong plot. Marston’s fetishes are kept mostly under wraps (as it were); Lana triumphs simply by getting rid of the bad guy in her life, not by teaching him the joys of bondage and loving submission. The feminism is less conflicted, but also a good bit duller. Or maybe the problem is just that pure, naive Lana is not a particularly sparkling protagonist; whether as modern scientist, Roman maiden, or pioneer daughter, her trust in her blandly evil boyfriend and love for her blandly gruff father are equally uninvolving. You can see why Marston didn’t care enough about her to even bother tying her up.

As is often the case in this series, as Marston goes, so goes Peter; the artist doesn’t seem nearly as inspired as in his last couple of outings. Still, there are a couple of moments. The duo does some more experimenting with wordless action sequences, and again the effect is lovely:

This is an interesting moment too.

Wonder Woman is using a pole to pick up a fan so the blades can cut the ropes tying Etta. I’m not sure the sequence entirely works; it’s hard to figure out whether WW is supposed to be moving up or down in that first panel, and the way the image is cropped, cutting off the end of the pole and the bottom two-thirds of Etta, seems awkward. But, again, I like the experiment with wordlessness, and the use of mutliple, Flash-like images of WW to convey motion is intriguing. Again, I wonder if this is something we’ll see more of in future issues. (I know we’ll see more of bound WW manipulating objects with her teeth — Marston lives for that.)

Going into the past also allows Etta to fully embrace her butchness:

Yep; in a past life, Etta was a gun-toting madam…er, that is, cantina owner. I like this intimation of jealousy as well:

Peter also makes Etta rather handsome there. The borderline men’s attire suits her. (More evidence that Marston doesn’t necessarily see women in drag as evil.

And…yeah, I think that’s really about all I’ve got to say here. You can tell the issue wasn’t firing on all cylinders because I’m not having to stifle the impulse to reproduce every single page. Peter’s art is still worth looking at, but there’s little evidence here of the breath-taking double page layouts that made last issue so stunning. But that’s the way it goes sometimes. We’ll see hope for better on the next one….

Music For Middle-Brow Snobs: Discopolis

This week’s download, with lots of krautrocky electro bleepery:

1. Artur Rubinstein — Chopin Mazurka #15, Op.24/2 CT 65 (Chopin: The 51 Mazurkas)

2. Sun Dawei — Crawling State (Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music)

3. Nara — Dream a Little Dream (Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music)

4. Kraftwerk — Metropolis (The Man-Machine)

5. Yellow Magic Orchestra — Technopolis (Solid State Survivor)

6. The Two Tons — I Depend on You (Horse Meat Disco)

7. Aavikko — Computopia (Nov0 Atlantis)

8. The Juan Maclean — A New Bot (The Future Will Come)

9. Legion of Two — It Really Does Take Time (Riffs)

10. Raekwon — Baggin Crack (Only Built 4 Cuban Linx II)

11. Raekwon — Surgical Gloves (Only Built 4 Cuban Linx II)

12. Raekwon featuring Jadakiss and Styles P (Only Built 4 Cuban Linx II)

13. Gene Page— Blacula (The Stalkwalk) (Blacula)

Download: Discopolis.

Last week’s download, if you missed it, is here