1. Behind the Curtain

I don’t remember exactly when or how it was that I first learned that L. Frank Baum, author of the Oz series of books, had called for the murder of all Native American people. But I do remember the information both shocked me and, in some ways, did not shock me at all. I had been doing research into colonialism and Indigenous history for a little while – mostly focusing on Canada, but including the rest of the Americas as well – and had become sadly used to encountering horrifying material.

Baum is not circumspect in his opinions about Indians, which he expressed just twice in editorials written for The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer . In the December 20, 1890, edition he declared: “The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians.” Just over a week later, on December 29, the U.S. Calvary killed hundreds of Sioux at Wounded Knee. In direct response to the massacre, on January 3 Baum wrote: “The Pioneer has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extirmination [sic] of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth.”

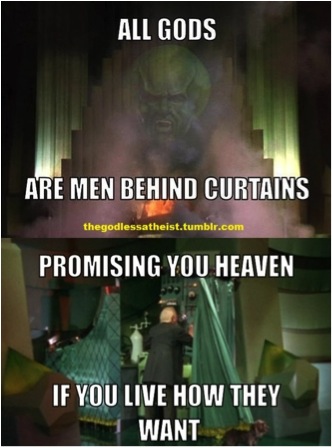

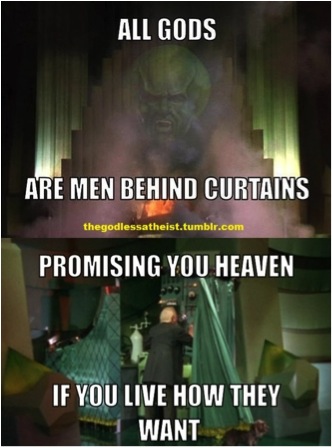

Among folks doing Indigenous studies Baum’s editorials are well known, so there never seemed much reason for me to write about them. At least that was the case until a friend of mine, Michael Ostling, invited me and three others to participate in a panel using The Wizard of Oz as a jumping off point to talk about issues related to the academic study of religion. That may seem like an odd idea, but it was based to some extent on two key points: 1) “religion” is a notoriously slippery term, and as a result it’s possible to link it to just about anything; 2) the machinations of the Wizard have been previously used by scholars as a metaphor for some aspects of religious activity. Russell McCutcheon, for instance, states:

In attempting to manufacture an unassailable safe haven for the storage of social charters and “worlds,” mythmakers, tellers and performers draw on a complex network of disguised assumptions, depending on their listeners not to ask certain sorts of questions, not to speak out of turn, to listen respectfully, applaud when prompted, and, in those famous lines from The Wizard of Oz, to “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.” (207)

The curtain metaphor applies very differently however to work by Sam Gill on a particular Indigenous ritual, the rite of passage ceremony for young Wiradjuri males in eastern Australia. In this ritual the older men at first fool the boys into thinking that a powerful spirit being is present among them, but then actually reveal their own trickery – much like if the Wizard himself had pulled aside the curtain, rather than Toto. In this way (according to Gill) the men induce in the boys “a disenchantment with a naive view of reality, that is, with the view that things are what they appear to be” (81). In other words the ritual helps to foster an understanding of religion, and life, that is complex and nuanced, that moves beyond the theatrics of smoke and thunder.

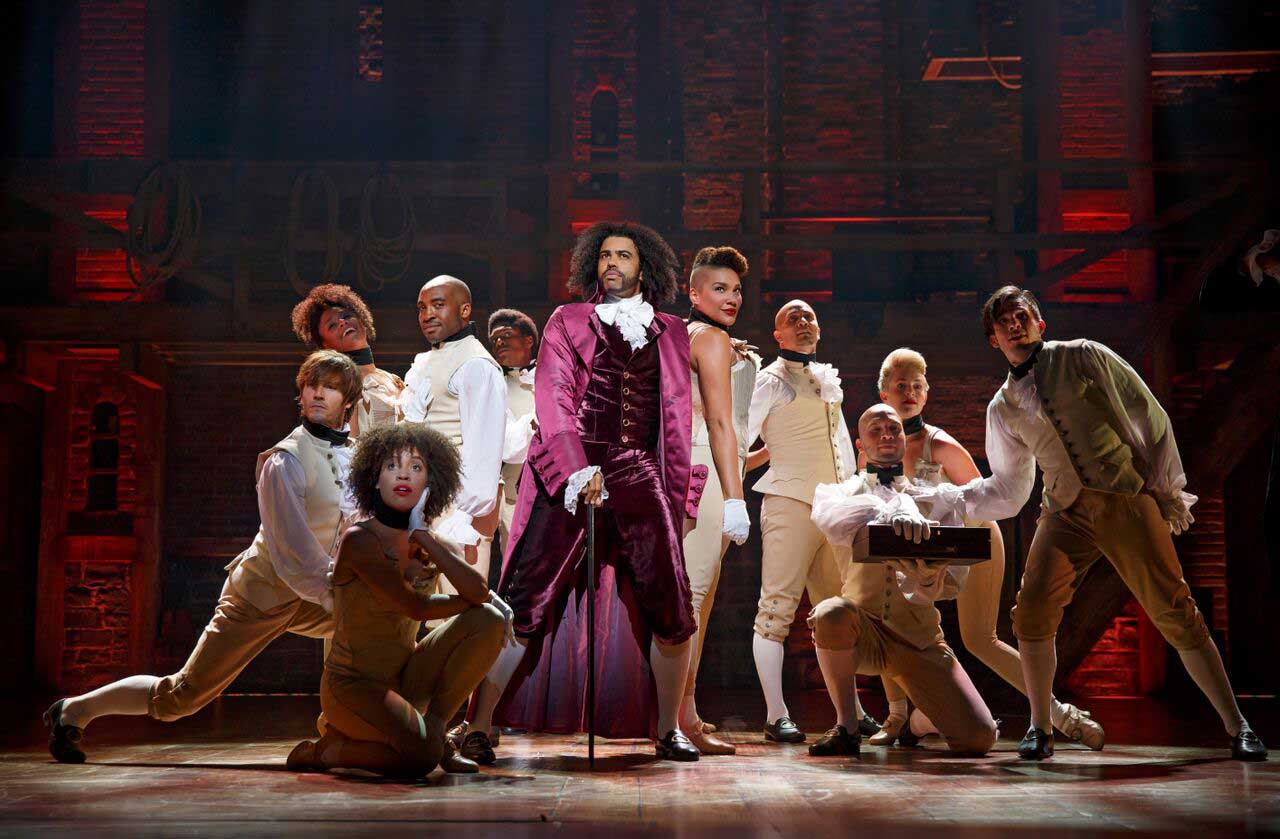

Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/232498399487979240/

All of which is to say that in many ways the stage had been set for some time now for a more detailed consideration of The Wizard of Oz and how scholars think about religion. In the end, the five of us presented our different takes on at the 2012 annual meeting of the North American Association for the Study of Religion. Four of us subsequently published versions of our papers in the Journal of Religion and Popular Culture in 2014, the 75th anniversary of The Wizard of Oz.

My own contribution to the panel centered on Baum’s editorials. Aside from studying Indigenous traditions, I have long been interested in conversations about religion and violence. One pattern in these conversations – the ones held both by academics and by regular humans – is that people tend to come to them having already decided what they think. Very simply: if you believe that religion is essentially “good” then you likely will make the case that “real” religion is not inherently violent (and so religion can be used as a kind of Ozian smokescreen to cover up the underlying motives of violence, but is never the “real” cause); and if you believe that religion is essentially “bad” then you likely are convinced, à la Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins, that it is in fact wholly responsible for a great deal of violence and suffering, and that the world would be much better off without it (religion in this view is the smokescreen, presenting itself as good and true and obscuring its underlying evil heart).

And so I wondered: did attitudes about Baum similarly impact scholars’ views of his work (or vice versa)? More specifically, were there connections between academic treatments of his genocide editorials and interpretations of both the first book in the Oz series, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and its 1939 movie adaptation? I wasn’t surprised to find that the answer seemed to be “yes.” (But while I was not surprised, I was [and am] still cautious: given that I’m looking at the ways in which people’s views of reality are shaped by their assumptions, it makes me itchy when my own assumptions appear to be borne out by the data I uncover.)

I am incredibly, unbelievably fortunate to have access to the University of Toronto library system, which seems to contain just about every book and article ever published on anything, ever. Which made it possible for me to read pretty much everything ever written on Baum, his work, and The Wizard of Oz. The first thing I noticed is that most scholars who write about this stuff do not mention Baum’s genocide editorials at all. The ones who do consistently fall into one of three categories:

- The majority see Baum’s work as very positive in various ways, and excuse the editorials (“he didn’t really mean them”; “you have to consider the context”; etc.).

- A few see Baum’s work as very negative in various ways, and accept the editorials more or less at face value (basically: “he was a genocidal racist”).

- A tiny minority see Baum and his work, including the editorials, as complicated and open to various, possibly contradictory, interpretations.

Anyone who’s interested can read the full account of my discoveries in excruciating detail in my article. Here, I thought I would just summarize some of the key ideas.

2. Baum is Good / Baum is Bad

The reasoning here is circular: Baum was a good guy, therefore the editorials clearly don’t show us who he “really” was, whereas his books reveal his innate positive qualities. There are three main points that scholars who like Baum and who also mention the genocide editorials tend to make about the initial Oz stories – both the 1899 book and the 1939 film:

- The stories are feminist: Dorothy is the hero/savior/protagonist. The most powerful characters in both Oz and Kansas are women (the good and wicked witches, Auntie Em, and Mrs. Gulch).

- The stories are anti-imperialist: The Wizard is revealed as both fraud and monster, sending a young girl and her friends on a suicide mission in order to protect his power. The more explicitly evil tyrants, the wicked witches, are destroyed and their people liberated.

- The stories celebrate diversity: Many different types of beings co-exist peacefully in Oz, a situation symbolized by the team of living scarecrow, mechanical man, anthropomorphic lion, human girl, and small dog. The only real inter-species problems are caused by the evil tyrants (e.g., the flying monkeys attack others because they are controlled by the witch).

These same three topics appear in the more negative readings of Baum, his first Oz book, and that book’s most famous movie adaptation:

- The stories are anti-feminist: The most powerful women in Oz who are in conflict with male authority (the Wizard) are the witches of the east and west, characterized as evil and deserving of assassination. Dorothy does not defeat these witches using her skills or intelligence, but by accident (using a house and a bucket of water). And the ending of the film makes it clear that the girl’s true “place” is at “home” – where she is now more than happy to do her domestic chores.

- The stories are pro-imperialist: The Wizard, in the end, is shown as kindly and avuncular; everyone seems to quickly forget that he tried to send Dorothy et al. to their deaths (!). Dorothy for her part is a helpful invader/colonist, who receives thanks and praise from the native inhabitants for her interference in their world (unlike the United States’ 2003 experience in Iraq, Dorothy is in fact greeted as a liberator upon her arrival in Oz).

- The stories are segregationist: Oz is (mostly) peaceful because its constituent “races” are kept separate from one another, each community in its own place (like Munchkinland). The diverse team of Dorothy and her new friends is the exception that proves the rule.

One of the more interesting examples of how assumptions about Baum impact interpretation of the Oz stories involves the poppy field. Batting for the pro-Baum side, Evan Schwartz in Finding Oz refers to the fact that, after WWI, poppy fields came to represent war victims: “The red color was said to come from the blood of the slain, serving as an emblem of commemoration” (190). Schwartz combines this perspective – which emerged of course after the original publication of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz – with his belief that Baum in fact disapproved of the genocide of Native Americans, and concludes that the poppy field in Oz “can be read as a powerful symbol of Frank’s – and America’s – sadness over the destruction of native cultures” (190).

Thomas St. John sees things differently. In the unambiguously titled “Indian-Hating in ‘The Wizard of Oz’”, St. John argues that various symbolic elements of the story reveal Baum’s generally racist perspective, and his particular desire to help bring about “the extermination of the American Indian.” The poppies in this reading are not about the war dead, but dangerous narcotics, associated with Native Americans through an impressively convoluted, if not entirely coherent, line of reasoning: “The Deadly Poppy Field is the innocent child’s first sight of opium, that anodyne of choice for pain in the nineteenth century, sold in patent medicines, in the Wizard Oil, at the travelling Indian medicine shows. Baum’s deadly poppies are the poison opium, causing sleep and the fatal dream.”

3. It’s Complicated

Essentially, folks who take the third approach to Baum and the Oz stories recognize that there are merits to many different interpretations, that whether or not Baum really meant what he wrote in those editorials his Oz stories are nevertheless ambiguous and complex, and lend themselves to a host of (often contradictory) understandings. Dorothy performs selfless, heroic acts and wants to go back to the farm. The Wizard is both murderously duplicitous and genuinely helpful. Oz is both diverse and segregated. The Witch of the West is both villain and victim.

Source: http://www.juxtapost.com/site/permlink/d8a43760-91e6-11e1-a833-533dd5490f0e/post/wizard_of_oz_is_a_pretty_messed_up_story_honestly_/

Katherine Fowkes is one of the few commenters who not only recognizes the inherent impossibility of arriving at a definitive reading of The Wizard of Oz, but regards this impossibility as a selling point. In The Fantasy Film she suggests that “the popularity and staying power of Wizard and other classic films may lie precisely in their myth-like ability to juggle conflicting ideas and impulses, thereby providing the possibility of various and sometimes opposite interpretations” (61). Her point here reminds me of Chris Gavaler’s discussion of Cinderella and the “minimally counterintuitive superheroes,” the key idea being that stories and characters are often particularly memorable because they occupy the “sweet spot” of the “weird-but-not-too weird.” That seems an apt description of many tales from both Baum and the Bible.

Fowkes’ take on The Wizard of Oz also reminds me of one of Paul Ricoeur’s central ideas about interpretation, namely that texts comprised of metaphors and symbols lend themselves, by their nature, to various understandings. We must “resist,” he says, “the temptation to believe that each text has its own correct interpretation, its own static, hidden meaning,” and instead recognize that “reading is, first and foremost, a struggle with the text” (494-5). The point is not that a given text can mean anything – interpretations must still be based on reason and evidence. There is virtually no evidence that Baum’s poppy fields, for instance, symbolize either his sadness over the treatment of Native Americans, or his desire to see them wiped from the face of the earth. But there is reason to think that his Oz stories have several things to say about gender, imperialism, and diversity – even if those things don’t always agree with one another.

For me, this is where the real (and really simple) connection to religion comes in: however you define it, “religion” is waaaay more complicated than The Wizard of Oz (!), and religious stories are not just myth-like but involve actual myths. It therefore seems entirely sensible to imagine that religions are also open to a host of reasonable yet divergent interpretations. This is of course a HUGE topic on its own, and one that I’m not going to go into here. I really just want to suggest that recognizing actual complexity – in stories, religion, people – can help us avoid shallow, one-sided, and possibly harmful interpretations based on simplistic, and simplifying, assumptions. Again, it’s a ridiculously simple idea, but one that I think too often gets lost in all the shouting about what things “really” mean.

Works Cited

Fowkes, Katherine A. The Fantasy Film. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Gill, Sam D. Beyond the “Primitive”: The Religions of Nonliterate Peoples. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1982.

McCutcheon, Russell T. “Myth.” Guide to the Study of Religion. Ed. Russell T. McCutcheon and Willi Braun. Cassell: New York, 2000. 190-208.

Ricoeur, Paul. “World of the Text, World of the Reader.” A Ricoeur Reader: Reflection and Imagination. Ed. Mario Valdés. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991. 491-497.

Schwartz, Evan I. Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

St. John, Thomas. “Indian-Hating in ‘The Wizard of Oz.’” CounterPunch 26-28 June. 2004.