(Black and White and Startlingly Offensive All Over – Part 5)

Readers looking for reviews, synopses and reading guides pertaining to Gene Yang’s American Born Chinese should head straight to the links above.

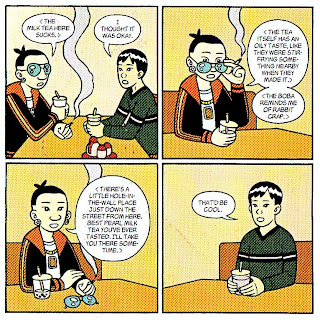

(1) Gene Yang’s comic concerns an American-born Chinese boy called, Jing Wang, and his journey of self-discovery through the largely white American landscape of his new high school. It has been described as a personal though not autobiographical work, the creation of which helped the author work through a number of problems.

I asked an Asian American friend who collects Yang’s art why he enjoyed American Born Chinese. He wrote back saying:

“For me, growing up Chinese in the US (and specifically, a very white town), I could relate to Gene (as the story is somewhat autobiographical). I enjoyed everything about the story: I’m a sucker for Monkey King, I liked how the three stories converged at the end…even the horrible racist caricature, something I would normally take great offense to, I thought worked well in the context of the story…I think the book resonates with anyone who has felt like an “other”…so it’s not necessarily specific to ABCs. I’ve met Gene and had some nice talks with him…Derek Kirk Kim said that ABC is a book he wish was around when he was a kid…so I’m happy for all the kids now, like my daughter, who have a book like ABC as part of their library”

I should add here that I found Yang’s book largely unprofitable both emotionally and intellectually speaking when I read it a few years back and my impression has changed little following my current reappraisal.

It is, however, notable for its close examination of the complex relationship between Asian Americans and their Eastern and Western heritage. Yang’s alteration of a famous segment from Wu Chengen’s Journey to the West (to fit in with his Catholic faith) is probably representative of this aspect of his comic. Kristy Valenti’s interview with Gene Yang in The Comics Journal #284 explains some of his motivations:

“There have already been a lot of adaptations of the Monkey King story…it’s almost like a genre in and of itself, adaptations of Journey to the West. When I was doing research on on the Monkey King, I realized this and I thought I couldn’t bring anything new to the table…I decided to approach it from an Asian-American outlook. And the way I decided to do that is by combining the two foundational stories from these two different cultures: the Monkey King story and the story of Christ…I would say it’s more C.S. Lewis-y than what you would find in medieval Catholicism.”

and later…

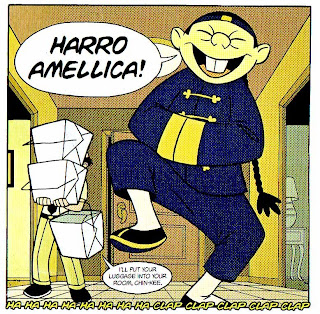

“…in the final scene, Jin is still speaking in English even though Wei-Chen’s speaking in Chinese….for me personally a lot of it is about finding who you are, having the definition of who you are be informed by both Western and Eastern cultures and making something new out of it. I think that’s what Asian-Americans are in the midst of doing right now…I think for Asian-Americans the temptation is to completely deny the Asian side, the Eastern side. And when you do that, you make the legends and the mythologies and the culture of your parents into these stereotypes. So that’s why I had the Monkey King become Chin-Kee.”

I don’t know if Journey to the West can be described as “the” foundational story of the Chinese people but it is certainly one of the most important works of classical Chinese literature. Here are some scenes from Yang’s comic juxtaposed with corresponding episodes from a famous adaptation:

[The following images are from a low quality English-Chinese bootleg translation. The original comic was published by the Shanghai Fine Arts Publishing House.]

Over the course of his comic, Yang not only relates his slightly altered version of the origins of the Monkey King (otherwise known as the Monkey God in many parts of Asia) but also transforms Monkey into a distant cousin of his protagonist – a caricature of all things Chinese.

This cousin, Chin-Kee, represents Jin Wang’s grotesque view of his Asian heritage as well as his acceptance of various stereotypical views promulgated by Western society. It is only following Jin Wang’s epiphany at the close of Yang’s comic that Chin-Kee’s true and more illustrious identity is revealed.

(2) As would be expected, the liberal use of racial slurs (“chink”, “nip” etc) by Asian Americans and white Americans (both in Yang’s comic and in reality) is something which occurs rarely in Chinese majority nations. The former group probably feel they are in the process of reclaiming such terminology in the way African Americans have sought to reclaim the word “nigger”. I can’t say that I find this approach particularly useful but then again, I’m not Asian American. If anything, it’s a bit jarring for me to hear these terms strewn about generously in conversations or in on-line chat rooms.

In Singapore (where I live), the racial slurs are directed at other minority races (Caucasians, Malays, Indians and even mainland Chinese). Singapore is an ethnically diverse country where the lingua franca is English and the population over 70% Chinese. Approximately one third of its population of 5 million has foreign citizenship, a factor which has led in recent years to growing social tension. It has to be said though that the situation is considerably less acute than the discrimination directed against foreigners in South Korea (which is more racially homogeneous) as described in a recent New York Times article concerning a South Korean woman and her Indian boyfriend.

For better or worse, Singapore has long had strict laws against racial incitement as demonstrated by the recent arrest of a number of bloggers for racist content on their websites. The bloggers were Chinese and their targets Malay (who constitute 15% of the population).

For some, this would be justification enough for William Gibson’s somewhat exaggerated and completely unrelated article on Singapore for Wired magazine (“Disney Land with the Death Penalty”) where he writes, “…and you come to suspect that the reason you see so few actual police [in Singapore] is that people here all have, to quote William Burroughs, “the policeman inside.” Of course in this case, the police were having a ball of a time on-line.

Singapore’s Minister for Law reiterated this stance in a Q & A at the New York State Bar Association (NYSBA) Rule of Law Plenary Session in October 2009:

“Freedom of choice must include the right to make bad choices. But where it impacts society, and where it impacts on key aspects, say for example, stability, society should have a right to have a say. Let me explain that by specific reference to an illustration. Let’s say, hate speech on the internet or publications. If anyone stood up and said I am expressing or I am exercising my right of free speech by saying that “all Jews are hateful”, or “all Muslims are bad’, we will arrest and charge him. Because for us, that freedom of expression does not extend to this sort of hate speech where violence against a particular ethnicity or religion or belief can be encouraged. And we have charged people for putting up such notices. We are particularly sensitive about it in our Chinese, Muslim, Hindu context. People have been charged for putting up notices against one or the other ethnic communities where it goes beyond some expression of opinion to incite them towards violence.”

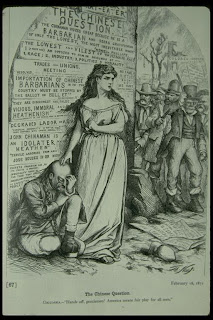

(3) These are moves which would meet with strong resistance in a liberal Western society. While Yang directs a large amount of his ire at Patrick Oliphant in the pages of his book, there is no indication that he would deny Oliphant the right to disseminate his brand of “racism”.

Over the course of American Born Chinese, Yang not only names his racially challenged high school after Oliphant…

…but also quotes directly from one of Oliphant’s offending editorial cartoons.

Oliphant is of course well known for using racial caricatures in his cartoons. In this case, his animosity was directed at the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Oliphant’s cartoon is objectively offensive and designed as such. In fact, the only adequate gauge for its effectiveness lies in its ability to draw a response from its target (in this case, not so much the CCP which could care less but Chinese in general). Its ability to draw the knowing nods of the majority of Americans who have a deep antipathy towards the CCP is of course important but hardly newsworthy and hence only a small measure of its success.

Controversy is mother’s milk to the political cartoonist. This is amply demonstrated in an article for the New York Times by Francis X. Clines who writes:

“Mr. Oliphant feels that the ”confrontational art” of political cartooning needs a boost from provocative work like Mr. Genn’s if it is to survive the homogenizing pressures of American culture. ”We are drowning in political correctness and somebody’s got to kill it,” he said. ”It’s the ruination of my business,” he added, citing individual newspapers that withhold his more controversial work or quickly apologize for it when the first complaint is lodged.”

And later…

“Mr. Oliphant’s inclination is to pick on everyone and never apologize for what he does. ”You have to get mad in this business, work yourself up to a boil once a day,” he said, as if this precious work dynamic can only be dulled by trying to keep in mind the multiple sensitivities of his variegated audience.”

It must be said though that such cartoons are as demanding on the satirical and artistic abilities of the cartoonist as drawing a large, beautifully cross-hatched penis on the editorial page of the New York Times.

It is not too difficult to see why Oliphant’s cartoon was seen to be threatening by some Asians living in America – that is, individuals with a vested interest in making the U.S. a more accommodating place for Asians. For the majority of Chinese throughout the world, however, Oliphant’s cartoon may simply confirm deep seated prejudices against Caucasians and the West.

[Not a political cartoon but a famous soap advertisement poster.]

With the passage of time, such cartoons may come to be seen as a marginally useful cultural and historical markers. Just as the Africans in Tintin in the Congo or Ebony in Will Eisner’s The Spirit continue to provide silent rebukes several decades down the line, such cartoons highlight the failings of a significant number of modern day political cartoonists. This is a form which consistently elevates superficiality and sensationalism over depth and intelligence. I for one will not mourn its passing.

[A positive image by a slightly more enlightened cartoonist, Thomas Nast.]

______________

Update by Noah: The whole racism roundtable is here.

Great post.

I found the speech by Singapore's Minister of Law to be particularly interesting. I'm not by any stretch an expert on Singapore, but I assume that their restrictions on hate speech are a direct response to the type of racial/religious violence seen in Indonesia and other countries in South Asia. Or am I completely wrong?

Thomas Nast had a spotty record on race. When the U.S. became more racist following reconstruction, so did he.

I'd be curious to know the year that Nast cartoon you reproduced was from. Do you know, Suat?

Richard: There were race riots in Singapore during the 60s. The Wikipedia entry above also links to the Maria Hertogh affair and a post independence race riot in 1969. These are probably some of the root causes for the government’s concerns about racial incitement. The racial and religious strife in neighboring countries merely reinforces their behavior.

Noah: Actually, Nast’s reputation as a racist precedes him. There are also his Irish Ape Men – one of which appears in the “pro-Chinese” cartoon above. The Nast cartoon reproduced in the article is from 1871. However, he was doing this kind of material even during the 1880s. In fact, the writer here feels (?mistakenly) that one of his “pro-Chinese” cartoons is racist. It’s described by the Thomas Nast site linked to in the article as “Cartoon. "A Matter of Taste." (c. 1883). Thomas Nast. (John Chinaman refuses Soup in Kearney's Senatorial Restaurant–refers to legislation pertaining to Chinese Exclusion Act).

Hey Suat. Yeah, 1871 would be in the middle of Reconstruction.That Chinese cartoon is similar to this one from 1965 dealing with blacks, which is pretty straightforwardly not racist, I think (the solider is not stereotypical, is shown as having served his country, etc.) The racist one I linked to above is from 1974. So yes, I'd imagine he got worse into the 1880s, not better. (That's one of the things about the post reconstruction period; people tend to assume that racial attitudes get better over time, but following the civil war and reconstruction, they actually got worse.)

what page is the quote: it's easy to become anything you wish so as long as your willling to forfeit your soul' on? i need it ASAP for an eassay… .please help!

Hi there Suat Tong,

Just came across your blog whilst trying to look for a comic/story book that I read when I was younger. Do you have the name/author of that black & white Journey to the West scans that you’ve uploaded?

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_d-f5Fyep9jI/Su0mJMorKFI/AAAAAAAAAHM/sVnKHNlOdm8/s1600-h/Journey+West+03.jpg

Thanks in advance!

Alex (Malaysia)

Unfortunately I don’t have the books with me at present so I can’t help you in this area. There’s a bibliography of authors/artists on these comics but I don’t have that on me at present either. As you know, these stories came in the form of small booklets and the Journey to the West comics were worked on by a rotating series of artists.

Hi there Suat Tog,

Refer to Alex’s message, I also read the book series like those black and white pics :http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_d-f5Fyep9jI/Su0mJMorKFI/AAAAAAAAAHM/sVnKHNlOdm8/s1600-h/Journey+West+03.jpg.

You said that you don’thave copy of the version. Pls tell me where you get the pictures from. Pity please :)

Oh it’s my copy of the book which is an old bootleg translation from Singapore decades old. I just don’t have it on hand. The Chinese have been pretty good at reprinting the comics in proper format in recent years. So you might be able to find it online or some shops in China. Even more likely in the year of the Monkey? The English version might only be available in Singapore though.