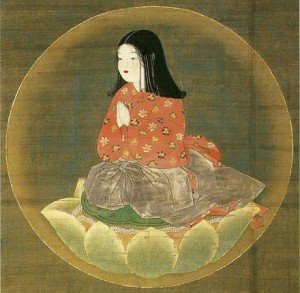

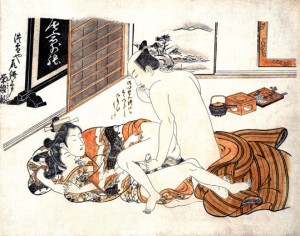

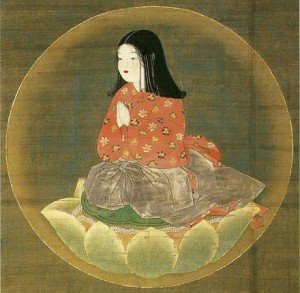

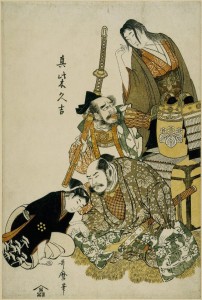

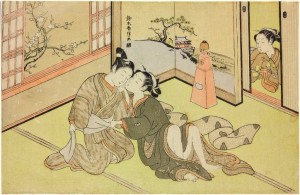

A print of a beautiful boy, in the style of bijin-ga, “beautiful-woman pictures” (Suzuki Harunobu, A Wakashu Looking at a Painting of Mt Fuji, c. 1650)

If you’ve been exposed to any Japanese media, you’ve almost certainly come across the figure of the bishounen; beautiful, doe-eyed young men who smile radiantly from the covers of manga, anime, J-pop CDs, and popular movies. The credit (or blame) for the profusion of these prettyboys is usually laid at the feet of shoujo manga and the generations of fangirls raised on its sparkles-flowers-and-gaint-eyes esthetic. Although that certainly has something to do with the popularity of the modern bishounen, the ideal of the beautiful, desirable, androgynous boy has been circulating in Japan for hundreds of years. Forthwith, a not-so-brief history of the bishounen.

Warning: NSFW images after the cut.

“Ichi chigo ni sanno”: Acolytes first, the mountain god second

The oldest standardized image of the beautiful boy is the chigo (literally “child”, usually translated “acolyte”); boy-attendants at both Shinto and Buddhist monasteries who performed some peripheral religious duties, including assisting in ceremonies, filling out processions, and performing religious and secular songs and dances, as well as acting as personal servants to their monks. Boys were considered eligible for chigo-hood between age 7 and the coming-of-age ceremony (about 15 in the medieval era, late teens or early-20s in the Edo period)[1]; some were aristocrat or samurai-class boys sent to monasteries for an education, some were novitiates who hoped to become ordained, and some were merely servants, hired for wages or purchased outright by their “brother” monk. Unlike the older boys and men who had already taken holy orders, chigo were permitted (and often encouraged) to grow their hair long, wear silk robes, and use makeup (face powder and rouge, sometimes tooth-blackening paste). This reflected their two major roles: to provide beauty and color in both ceremonies and daily life, through music and dance performances as well as their own physical charms, and to serve as romantic and sexual partners to their brother monks. Aside from physical beauty, the ideal chigo possessed grace, nobility and cultured achievements, particularly in music and poetry; many of the chigo love stories cast the boy as a son of an aristocratic family, the eminence of his background providing a rationale for his abilities.

Traditionally, the origin of Japanese nanshoku (literally “male color”, with “color” having the implication of erotic appeal, and therefore generally translated “male love”) is ascribed to Chinese influence. By the 14th century there were a number of legends crediting Kukai (posthumously dubbed Kobo Daishi, or “great teacher transmitting the Dharma”), founder of the Shingon (“true word”) sect of esoteric Buddhism, with importing nanshoku along with religious doctrine upon his return from China in 806. Kukai himself is often depicted in religious iconography as a chigo, which seems appropriate.

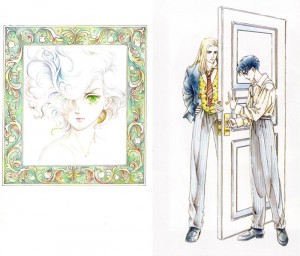

The Chigo Daishi, or Kukai in his form of a beautiful child (Anonymous wall scroll, early 14th c., Art Institute of Chicago)

An anonymous 16th-century text, Kobo Daishi’s Book, offers hints on boy-management said to have been obtained (in a dream-visitation) from the man himself:

After an acolyte has spoken, observe him carefully. The acolyte who speaks quietly is sensitive to love. To such a boy, show your sincerity by being somewhat shy. Make your interest in him clear by leaning against his lap. When you remove his robes, calm him by explaining exactly what you will be doing. […] An acolyte may be very beautiful but insensitive to love. Such a boy must be dealt with aggressively. Stroke his penis, massage his chest, and then gradually move your had to the area of his ass. By then he’ll be ready for you to strip off his robe and seduce him without a word. [Trans. Schalow]

Other tips for seduction include flattery, pretending an interest in his hobbies, and regaling him with tales of warriors and other topics of interest to boys. The work concludes with a survey of positions and penetration techniques for anal sex, and a tip from the author himself, to add to Kukai’s wisdom: boys with tiny mouths have tight asses (this parallels a piece of folk wisdom regarding women’s attributes).

Kobo Daishi’s Book can be interpreted as a tongue-in-cheek take on the storied monastic obsession with boy-buggery (the first section, on hand-signals, and the last on positions, mimic teachings on meditation), or as sincere advice on a topic dear to the clerical heart. Less prurient advice can be found in the 12th-century Shingon text Uki by Prince Shukaku (1150–1202), abbot of Ninnaji temple. Shukaku counsels that chigo should carry out their religious duties diligently, behave in a decorous manner, dress elegantly, and devote their time to the study of music, poetry, and literature. He points out that one’s status as chigo is temporary, only four or five years; boys should make the most of it.

Mentions of love affairs between monks and chigo occur from the 13th century at least; the collections Jikkinsho (1252) and Kokonchomonju (1254) both feature anecdotes of priests who fall in love with beautiful chigo dancers at temple cherry-blossom festivals. More extensive stories occur in the chigo monogatari (“chigo stories”), a group of about a dozen texts written between the 14th and 16th centuries. The oldest of these, an anonymous hand scroll dated 1321 and given the later title chigo no soshi (“chigo handbook”), has the distinction of possibly being Japan’s oldest preserved piece of pornography (the original is said to still be in the possession of the Daigo-ji temple). The chigo no soshi contains five scurrilous stories, with suitably filthy illustrations, all on the topic of chigo who take pity on men, not their masters, who desire them, and relieve their admirers’ suffering by letting themselves be screwed senseless. The first and longest story comes in two versions: the first, told through the main text, is of a devoted chigo of an elderly monk who undergoes elaborate precoital preparations to ensure that his enfeebled master can achieve penetration. The second, told through the illustrations and accompanying dialogue, has the boy fornicating wantonly with the manservant who is supposed to be preparing him for his master’s bed.

One of the boys from the chigo no soshi, pretending like we don’t know what’s going to happen next (Anonymous hand scroll, detail from a later reproduction of the 1321 original)

The remainder of the chigo monogatari are rather more respectable. The typical story is of a monk who falls in love with a beautiful chigo, only to have the boy die tragically some time later (of illness, murder or suicide), causing the monk to realize the transience of all things, renounce earthly desires, and thus achieve enlightenment. Some of the stories are primarily religious parables with the romance reduced to a plot point, others are primarily romances or tragedies with minimal religious import. One of the longest is Aki no yo no nagamonogatari ( “A Long Tale for an Autumn Night”, before 1377), the subject of a beautiful set of 14th century handscrolls. The monk Keikai of Mt Hiei has a dream of a beautiful boy, and the following day espies just such a boy in the grounds of the rival temple of Miidera:

[H]e saw a youth of about sixteen. He was wearing a gossamer robe embroidered with a design of waves and fishes over an undergarment of pale crimson, the skirts of which fell long and gracefully from his slender hips. Evidently unaware that he was being watched, the boy came out from behind the bamboo screen into the garden and broke a spray of blossoms from a branch which hung low as though heavily laden with snow. […] As he walked softly around the game court with the blossoms in his hand the ends of his long hair, swaying as gracefully as sea grasses, became entangled in the branches of a willow and held him bound. He turned around abstractedly, and the Master saw the very face, the same expression that, ever since his dream, had so captivated him that he had not known where he was. [Trans. Childs]

The monk and chigo (who turns out to be Lord Umewaka, son of the Hanazono Minister of the Left, in accordance with the above-mentioned fetishization of aristocratic boys) exchange poetic love-notes and start a happy love affair, but when the chigo goes missing (abducted by tengu) the monks of Miidera blame Mt Hiei and war ensues, in which Miidera is destroyed. When Umewaka returns and sees the carnage he commits suicide out of guilt, leaving Keikai, devastivated, to become a hermit and attain salvation. At the end of the story it is revealed that the boy was in fact a manifestation of the bodhisattva Kannon, sent to bring Keikai to enlightenment.

The violence directed against chigo in the chigo monogatari may not be solely to provide dramatic tension or didactic effect. Surviving sources suggest that there were numerous rivalries between monks over favored chigo, sometimes leading to murder. These disruptions, as well as the fact that most sects agreed that monks should, ideally, be entirely chaste, led some monasteries to ban chigo, such as the edict of former emperor Go-Uda at Daikakuji in 1324. Most, however, continued to permit them; a 1355 edict from the Gakuenji temple in Izumo explains that chigo are not only needed to perform religious duties but also to “alleviate the coldness of lonely nights”.

At the end of a boy’s tenure as a chigo he would normally either become a monk (and might then take a chigo of his own) or return to his family to take up whatever position his station in life dictated. For those boys who were indentured servants, however, there was no such guarantee. We have the diary of one Jinson, the abbot of Daijoin temple, which contains the details of several of his chigo. In 1461, Jinson recruited a low-born 15-year-old named Aimitsu to be his chigo. Six years later, Jinson purchased the boy outright from his father. Aimitsu became a cleric at age 26, in 1472, still in Jinson’s service and without ever having formally become an adult. After a period of illness, he committed suicide at age 28. Several scholars have speculated that the (very late) loss of his chigo status caused Aimitsu to kill himself; of too low a social class to become a full-fledged monk and effectively Jinson’s property, Aimitsu may have felt he had no other recourse.

Shudo and Bushido

The noble and samurai classes were not blind to the attractions of beautiful boys; the equivalent of the monastic chigo was the wakashu (literally “young person”), a boy, like the chigo, in the stage between early childhood and the coming-of-age ceremony. Wakashu wore a distinctive hairstyle, with a small shaved portion on the crown of the head and long forelocks (maegami) in front; they were also permitted to wear long sleeves (furisode), bright colors, and flower prints on their kimono, all things which were suitable for women and children but not adult men. Boys of the samurai class were employed by noble households as page-boys; like chigo, the page’s duties included being decorative, entertaining their lord and his guests with dance and music, and accompanying their lord to bed if required, but unlike the chigo, a noble’s pages were part of his militia and expected to fight when necessary, despite their age. Samurai-class wakashu wore twin swords like their elders and were expected to willingly receive training in the martial arts.

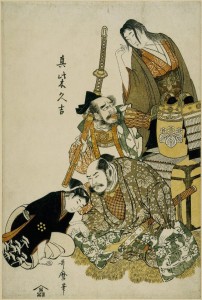

Mashiba Hisayoshi (a reference to the lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi) and a page-boy (identified as Ishida Mitsunari). One of a series of prints that got the artist in trouble for mocking the love-affairs of the powerful. (Kitagawa Utamaro, 1804, British Museum)

Page-boys were expected to be faithful to their lord (on pain of death), but boys outside such positions were fair game for other men. As with chigo in monasteries, wakashu could cause dissention among rivals, and regulations both formal and informal were set up to control such relationships. One form of control was the formalization of the pursuit of wakashu as a do, or way: the wakashudo (“way of wakashu”), generally shortened to shudo (the term first appears in the 15th century). The Hagakure (c. 1716), which sets out rules for the warrior’s life (from the perspective of the 18th century, after over a hundred years of peace), takes a particularly hard line on shudo: a boy should have only one lover during his youth, and he should only accept the man after several years of “steady amorous intentions”. Once a lover has been chosen, would-be buttinskis should be dealt with harshly; the boy should cut them down if they won’t leave him alone. The partners in shudo should abstain from women and should be prepared to give up their lives for each other, at least so long as the relationship pertains.

Other texts set out the terms of a shudo relationship. The most important trait in a wakashu, according to the Shin’yuki (1643) was nasake (“compassion”), like that demonstrated by the boys in the chigo no soshi; the sensitivity to an admirer’s suffering and the willingness to relieve that suffering through his sexual and romantic availability. A wakashu, in turn, should overlook his suitor’s status, wealth, and appearance, and even his own degree of attraction to the man, and value only the “sincerity” of the man’s affections, taking as nenja (“lover” or “admirer”) the first man who loved him deeply and faithfully. Shin’yuki aside, surviving texts suggest the boy’s appearance was usually the initial source of attraction. Valued characteristics were fair skin, long glossy black hair, red lips, flushed cheeks, and graceful movement. The suitor might also be taken with the boy’s musical ability on the flute or biwa (both male-specific instruments), and his skill at composing poetry, a widely-valued trait in both sexes.

A later edition of the Shin’yuki gives the ages at which a boy may be loved: they have childlike appeal between 12 and 14 (10-13 by modern count), are at the peak of beauty between 15 and 17 (13-16), and embody mature love between 18 and 20 (16-19). After 20 they are no longer suitable. The Wakashu no hara (17th century) gives roughly the same stages: a boy is a “blossoming flower” from 11 to 14, a “flourishing flower” from 15 to 18, and a “falling flower” from 19 to 22. Pursuing older youths, or those who had undergone the coming-of-age ceremony, was eccentric; pursuing boys not yet wakashu was in bad taste (not necessarily illegal or immoral, mind you, just tacky). For comparison, girls were considered to be at the peak of their beauty at 16, and among Edo’s licensed pleasure quarters, courtesans were considered not worth their keep after 20 or 22 unless exceptionally beautiful.

As indicated by the above, a wakashu’s status as erotic object lasted only so long as his status as wakashu. Saikaku Ihara’s short-story collection Nanshoku Okagami (“The great mirror of male love”, 1687) devotes its first 20 stories to love affairs of samurai-class boys. In two of these, a pageboy who has taken a lover not his lord, is spared from execution under pain of immediately shaving his forelocks and becoming an adult. By this means the merciful lord renounces his claims over the boy, but at the same time ends the boy’s (sexual) relationship with his lover.

During the course of a shudo relationship, the lover should teach the wakashu honor, duty, and the warrior code, and seek to provide a good role model through his own behavior; thus, shudo was promoted as having a mutually ennobling effect on the participants as well as assisting the youth in learning martial skills. A wakashu might wear face powder and furisode, but he was still seen as the embryonic stage of the fearsome warrior; in the Nanshoku Okagami, the narrator moves seamlessly from describing the youths fussing over their dress and hairstyles to recounting the fearless duels, vendettas, murders and ritual suicides they enacted. Between the inevitable onset of adulthood and the possibility of a violent end, the beauty of the wakashu was fleeting; they were often compared to the cherry blossom, Japan’s go-to icon of beauty, eroticism, and transience. Real people, like the historical warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune could be made over in the bishounen image to bring their appearance in line with the romantic appeal of a brave life and tragic end.

Performance, prostitution and commercialization

In 1374, the young shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu visited the Shinto temple of Imagumano to view the “monkey dances” performed by the temple boys, and returned home with the 11-year old (9 or 10, in modern count) dancer Zeami and his father Kan’ami in tow. Zeami was promptly installed as imperial favorite, and the dances and skits his father wrote for him, and those he wrote himself in later life, became the foundations of noh theatre. The shogun’s affair with Zeami occasioned considerable censure, not because of the underage boy-buggering but because the shogun had fixed upon a no-account commoner, of the lowest social class, upon which to lavish his affection. The courtier Nijo Yoshimoto, however, defended the shogun’s choice on the grounds that Zeami was uncommonly beautiful:

[When he dances he is] more beautiful than all the flowers of the seven autumn grasses soaked with the evening dew. […] I should compare him to a profusion of cherry or pear blossoms in the haze of a spring dawn; this is how he captivates, with the blossoming of his appearance. [Trans. Hare]

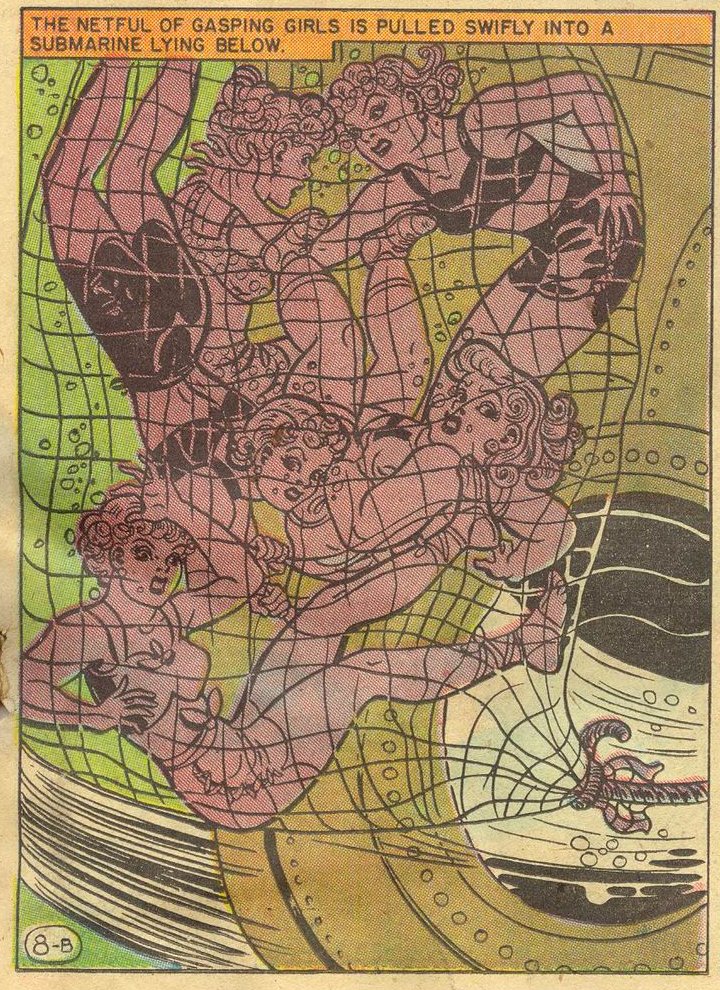

Both noh and traditional dance performances were associated with male prostitution, but the new theatrical form of kabuki was even more closely so. Born in the first years of the 1600s out of shows put on by brothels to advertise their goods, kabuki attracted considerable official interference because of its connection to prostitution, which the shogunal government wished to confine to the licensed pleasure quarters only. Early kabuki centered around song-and-dance routines and short skits depicting visits to the pleasure quarters and other suggestive situations, and the actresses would mingle with the audience between acts to provide such personal services as the patrons might desire. In a series of bans between 1629 and 1646 the shogunal government succeeded in driving women off the stage (not only in kabuki, but also noh, the more informal kyogen, and joruri puppet theatre as well), and tried to force more respectable subject matter by banning too-salacious material and requiring more developed storylines. All-male kabuki troupes had been in existence since at least 1612, so kabuki forged on, populated by attractive wakashu, some in female drag, and available to the audience as usual. In the next step of its never-ending and utterly futile attempt to break the link between kabuki and prostitution, the shogunal government first banned female impersonators (onna-gata, “woman-role”), and when that merely led to a rash of plays depicting nanshoku love affairs, in 1654 rescinded the ban but required all actors, regardless of role, to shave their foreheads in the adult male style. In the Nanshoku Okagami this is described as “like seeing unopened blossoms being torn from the branch.” Fortunately for all, the wakashu and onna-gata actors developed a fashion for little purple headscarves to cover their lack, which shortly became as much an object of erotic fixation as the wakashu’s forelocks.

Aside from the actors themselves, available after-hours for a suitable fee, there was a large contingent of “apprentices” who could also be engaged from tea-houses in the theatre district. Boys too young or too unskilled to act were dubbed iroko (literally “color children”, or, behind the metaphor, “love boys”), and although they were required to be in the employment of a registered theatre, many of them never set foot on stage.

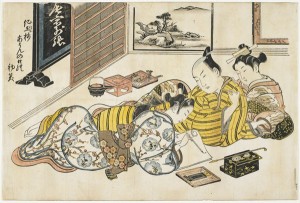

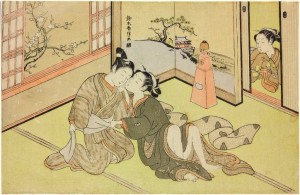

Kabuki actors entertaining patrons in a teahouse; the bedroom is off to the left (Hishikawa Moronobu, detail of a hand-painted scroll, 1685, British Museum)

Wakashu actors (or wakashu-gata, those not truly wakashu anymore but merely assuming the role for stage purposes) were considered most appropriate not only for female roles, but also for roles as romantic heroes and refined young noblemen. Wakashu were attractive to both men and women, and male prostitutes were available to both (sometimes at the same time, if you believe some of the erotic prints), although women seem to have preferred their boys a little older.

Besides the theatre districts, temple areas were particularly associated with male prostitution. Having a chigo required some commitment on the part of the “brother” monk; besides the cost of outfitting and the time for educating their charges, monks might be required by particularly demanding chigo to sign oaths of fidelity or give other promises of good behavior. If a monk did not want to make the effort, or if his monastery banned chigo, he could turn to the boy-brothels that sprang up around the better-known temples to serve both the monks and any interested parties among the pilgrims and travelers that the temples attracted. Monks’ exploits with prostitutes both male and female are a favorite topic in ribald poetry and stories and in the shunga prints of the 17th and 18th century.

In Saikaku Ihara’s picaresque novel The Life of an Amorous Man (1682), the sexually precocious protagonist, who has undergone his coming-of-age ceremony at the tender age of 14, makes a pilgrimage to the Hase temple and, on the way back, buys himself a pretty male prostitute who turns out to be ten years older than himself (much to his dismay). The humor of this incident hinges on a key detail of nanshoku; the receptive partner was expected to be pre-adult, a boy rather than a man. In this case, the very young age of the client and the rather extended “boyhood” of the prostitute manage to invert the normal course of things.

At this time, in the mid-17th century, shudo became disseminated to the urban masses, partly via the new-found publishing industry, which served up story collections like the Nanshoku Okagami, etiquette manuals (covering every detail from the first approach to the breakup letter when passion inevitably cooled), poetry books, collections of dirty jokes, and vast numbers of ukiyo-e prints, clean and pornographic. In 1676, the scholar Kitamura Kigin compiled Iwatsutsuji (“Rock azaleas”, first print edition 1713), an anthology of shudo-themed poetry collected from classical and religious sources, aimed at presenting an ennobling, estheticized view of male love for the modern reader. (Kigin deliberately omitted all licentious and coarse material, but his discards were happily taken up by publishers of cheap illustrated books and collections of satirical poetry, which regaled the reader with scatological stories of lustful monks, mercenary boys, put-upon prostitutes and so forth.) Shudo texts presented the pursuit of boys as a cultured pastime, like flower arranging or composing poetry.

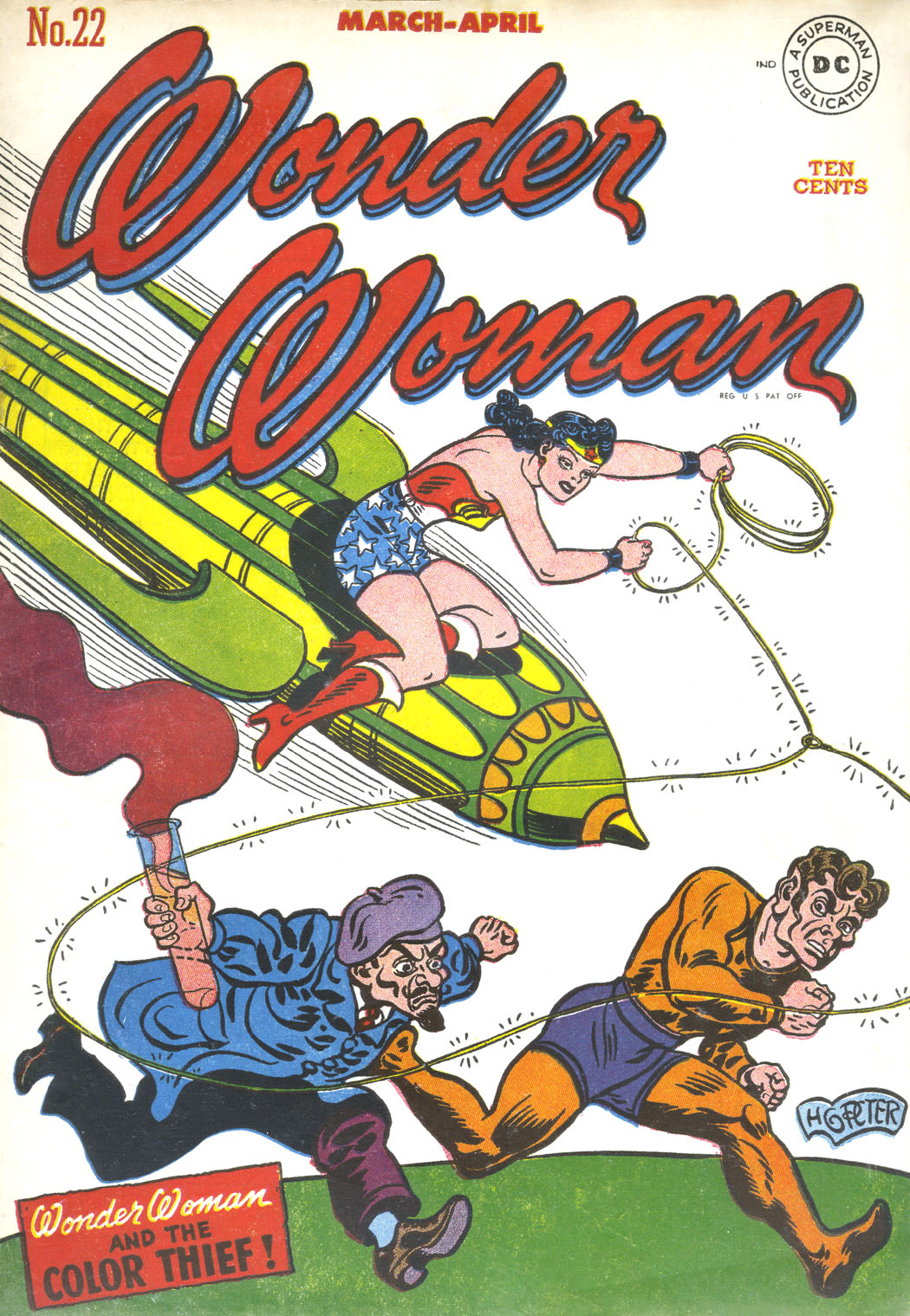

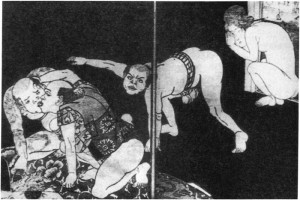

If shudo was something that one sought to do well, it was also something it was possible to do wrong. The most obvious failure of shudo etiquette was the pursuit of youths who were too old. One 17th-century chronicle of feudal lords mentions with some confusion a few who liked boys with hair on their legs, or even beards, and reports with relief that at least one had given up this “aberration” and returned to the appreciation of proper bishounen. An unjustly obscure 17th or 18th-century print shows three adult men getting frisky together; the print is obviously satirical, as the men are marked with every possible signifier of socially-undesirable hideousness: jowly faces, pug noses, thick lips, shaven heads, squat bodies, and the tattoos and clothing of lower-class thugs. In the corner of the print, a neglected female prostitute cowers in horror at the unlovely sight.

So totally not bishounen (unattributed late Tokugawa polychrome print)

“Plum and willow, wakashu or woman?”

The opposite of nanshoku is joshoku, “female colors” or “female love”. Both of these terms presuppose a male referent; that is, they designate a man’s interest in males or females, respectively. (Women’s inclinations apparently were not worth inventing terminology for.) Both literary and pornographic sources in late-medieval and premodern japan frequently assume an interest in both; shudo print sets often include one or two heterosexual pairings, and heterosexually-focused works might feature an occasional shudo scene, like Suzuki Harunobu’s c. 1770 Furyu enshoku Maneemon, in which the protagonist’s love-lives-of-the-world tour includes a visit to see an actor “entertaining” a patron (NSFW). In pornographic prints and raunchy stories, men pursue wakashu and women, women pursue wakashu, and wakashu pursue women and other, younger, wakashu. The kabuki play Saint Narukami and the God Fudo (1742) contains a salacious comic-relief scene in which the hero of the hour, Danjo, left to cool his heels in a nobleman’s waiting room, invents a transparent excuse to grope and dry-hump the lord’s pretty 13-year old son; after the boy fights him off (with cries of “pervert!”) he turns his persistent but unwanted attentions to a maidservant, whom he barrages with dirty double entendres. When she, too, gets away from him, he strikes a pose and quips, “That’s two cups of tea I’ve been denied!” (cue laughter).

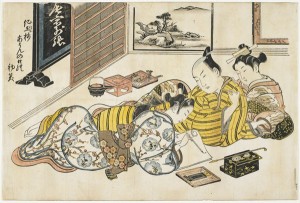

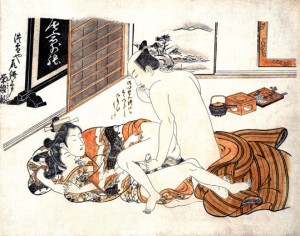

A man relaxes in a brothel with a boy (composing a poem) and a female prostitute (Masanobu Okumura, New Years gathering within a brothel, c. 1739)

Spot the differences: artists often borrowed each other’s compositions (Suzuki Harunobu, untitled print, c. 1740)

Wakashu were also the standard depiction of handsome young lovers, and feature in idealized prints as well as romantic stories. Kabuki actors were held in particular regard; both the male-role actors and the female impersonators were ardently pursued by 17th- and 18th-century fangirls. One of the less shudo-oriented stories in the Nanshoku Okagami tells of a young noblewoman who has a female impersonator with whom she is enamored smuggled into her quarters, attired in his stage drag to bypass the guards; there is a humorous description of her handmaidens literally falling over each other to get a look at the young man, their faces “pale with desire”. Unfortunately, they have gotten no further than the traditional precoital cup of sake before her brother returns and claims the pretty visitor for himself, leaving the poor lady frustrated.

An older woman seduces a pretty young thing (Suzuki Harunobu, probably from an album of erotic prints, 1765-1770, British Museum)

For the swinging Tokugawa gentleman, this of course raised the thorny question: how to keep your boyfriend off of your girlfriend, and vice versa? (Suggestion from period advice manuals: never let them meet.) A number of erotic prints show a man who catches his favorite concubine in bed with a boy (or conversely), and asserts dominance over the situation by screwing them both. Other prints show surprising collections of persons of both sexes in happy engagement, sometimes stacked like turtles. At least in the imaginations of a few printmakers, anything went.

The Meiji era: bishounen in a new world

After the forcible opening of Japan to the West in 1868, Japanese views of nanshoku began to be influenced by Western psychomedical views of homosexuality. On the one hand, this led to the pathologization of both homosexual desire and (more slowly and erratically) of the bishounen himself, whom Western theory positioned as an abnormal, feminized figure who must be firmly redirected on the path of proper masculinity lest he become a permanently perverted “invert”. On the other hand, the Western location of homosexual desire within the weak, effeminate passive who fruitlessly attempts to seduce the masculine heterosexual male failed utterly to mesh with the Japanese image of the active, adult man who courts pretty passive youths. Shudo texts had generally supposed that the chigo or wakashu had no sexual desire for their lovers and did not enjoy being penetrated (although Edo-region prints often show the boy partner with an erection, and some show the nenja masturbating him), so during Japan’s brief criminalization of homosexual anal sex per se, authorities were confused as to what to do with cases of men who offered themselves to other men as “bottom” outside of prostitution, a turn of events that Japanese legal codes had never contemplated.

Aside from the newly-discovered specter of the “invert”, popular understanding of homosexuality became increasingly relegated to the realm of adolescence. In Ogai Mori’s semiautobiographical 1909 novel Vita Sexualis, the narrator separates the students at his boarding school into two types: the nanpa (“soft crowd”) like himself, who are interested in fashion and women, and the koha (“rough crowd”) who are sports fans, idolize military figures, and reject women as feminizing, instead pursuing pretty younger boys and terrorizing the other students in the process. Other Meiji writers describe similar phenomena under other names; the predatory gangs of older boys in the boarding-school dormitory, or the teenage juvenile delinquents who prowl the streets of Japan’s cities, seeking out bishounen, preferably from upper-class families, to abduct and rape. Late 19th- and early 20th-century scandal-rags reported nearly weekly on sensationalized stories of attempted kidnappings, gang fights over the affections of boys, and other crimes laid at the feet of adolescent nanshoku-enthusiasts, whipping up a decades-long moral panic in the process. The koha, significantly, were always depicted as in their teens or early 20s; once a man hit adulthood he would naturally turn his attentions to women, as the more refined nanpa already did. And in this conceptualization, of course, the bishounen remains the blameless, socially approved and passive object of desire, as he was in former eras.

The koha panics faded by the 1920s, replaced in the minds of the moral guardians by crossdressed male prostitutes lurking in Tokyo’s parks by night. The bishounen, at this point, is split: one part relegated to the “perverse press” and the red-light districts, one pure, virtuous and thoroughly disconnected from any taint of homosexuality.

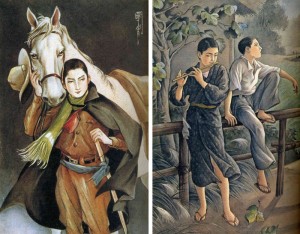

As part of the effort to raise Japan’s young men to a life of loyal service and devotion to their emperor, and to make a little cash on the side, publishers began in the 1920s to put out boy’s magazines, full of morally uplifting stories of heroic young men who do good deeds and diligently care for their families. These stories were illustrated by correspondingly idealized pictures of beautiful boys, such as those by Takabatake Kasho (also a prolific illustrator of girls’ magazines). As boys’ magazines moved into less didactic pulp-action territory after WWII, however, the doe-eyed vision of boyish perfection lost ground, and eventually fell by the wayside.

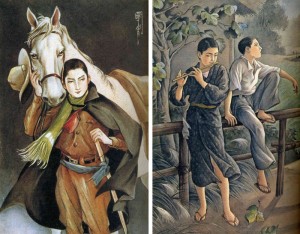

Two illustrations for 1930s boys’ magazines (Takabatake Kasho, from Bishounen Zukan, “The pretty-boy picture book”, 2005)

On the other end of the spectrum, the influx of American servicemen and other transients created a market for services that no longer fit the he’s-a-kabuki-actor-we-swear teahouse model. The English term “gay” was borrowed into Japanese as gei, to describe effeminate, passive men, especially those who performed as singers, dancers or hosts in the newly-emergent gei ba (“gay bar”). By the 1950s, a distinction was drawn between gei boy, who affected an androgynous look influenced by French gamine actresses, and “ladyboys”, who were overtly crossdressed. (The true Japanese homo, of course, would be tremendously offended to be categorized as either.) The gei ba developed over time into flashy clubs with cabaret revues and shows that catered mainly to foreigners, men who liked foreigners, and, soon, sightseeing straights; Japanese men seeking other Japanese men came together in tiny, hole-in-the-wall homo ba. Like New York’s Harlem in the 1920s, Tokyo’s gay district in the 1950s and ‘60s became a fashionably decadent place for an adventurous night on the town, where men and women could admire the spectacle put on by teams of pretty boys.

A “gei boy” of the 1950s, from Tomita Eizo, Gei, 1958 (via Ishida and Murakami, The Process of Divergence between ‘Men who Love Men’ and ‘Feminised Men’ in Postwar Japanese Media, 2006)

And now for something completely different: the bishounen in female media

In 1961 and ’62, Mari Mori (daughter of the Ogai Mori whose Vita Sexualis is mentioned above) wrote her three tanbi (“aesthetic”) novellas; A lover’s forest, I don’t go on Sundays, and Bed of fallen leaves. All three follow the same plot: an impossibly beautiful teenage boy is taken in by a wealthy and sophisticated (and much older) man, who keeps him in decadent luxury until the relationship is broken up by jealousy and violent death (murder, suicide, or both). Mari was noted for her lush prose, and she pours it all over her boys: their pale, transparent skin; their glossy hair; their luminous eyes, which “seemed to emit pale lavender flames”; their full lips “like fruit ripened by kisses”; their languorous movements and flirtatious glances. Their infatuated lovers surround them with exotic Western extravagances: custom-tailored suits, French soap, German cologne, imported cigarettes (that they wastefully stub out half-smoked), caviar, martinis, Rolls Royces and nightclubs. The boys address their lovers in feminine speech (but not in public), and the lovers, in turn, compare them to geisha and “Parisian courtesan[s]”. Despite appearing beautiful and innocent “like a cherub in a Raphael painting”, Mari’s boys are not entirely sympathetic; they are indolent, extravagant, wasteful, spoiled, childish, passive, persistently unintellectual (all the boys are dropouts, whereas all their lovers are highly educated), and not particularly concerned with morality. The other characters (and, one feels, Mari herself) are willing to overlook all their faults on account of their spectacular beauty and sexual desirability.

So, basically, Mari Mori invented boy’s love (although she doesn’t seem to have been very happy with the connection). It’s amazing how many old-school BL tropes Mari’s novellas cover: she’s got the seme/uke stereotypes, the fetishization of Westerners and the West (two of her men are half-French and everyone else “doesn’t look Japanese”; French or European origin stands for everything luxurious and desirable), the highly idealized characters (impossibly beautiful, wealthy, educated, and sophisticated – Guylan of Bed of fallen leaves is not only half-French, but half French aristocrat), the casual bisexuality (most of the characters have concurrent or former female lovers), the lushly-implied-but-not-shown eroticism (the sexual content of the novellas is, by modern standards, very discreet, although Bed of fallen leaves wanders into sadomasochism and heroin addiction before ending in murder-suicide), the melodrama, the misogyny (jealous and manipulative women abound), and the brutal downer endings (rare in modern BL but standard for older works). What she doesn’t have is BL’s emphasis on overwhelming, undying love; most of the men are obsessed, but none of the boys seem all that attached to their lovers. A lover’s forest‘s Paulo finds Gidou’s freshly-murdered corpse (courtesy of his jealous ex-girlfriend) and seems to regret the loss of his posh lifestyle more than anything else (and, at the end of the book, is about to be picked up by another infatuated older man who has been waiting in the wings for just such a chance). Bed of fallen leaves‘s Leo seems on the point of leaving his lover Guylan for a kinky Italian who whips him and gives him drugs, prompting Guylan to kill Leo and later himself. I don’t go on Sundays‘s Hans seems to accept his breakup with Tatsukichi (prompted by Hans’ ex-fiancée’s public suicide) with as much composure as Tatsukichi does. (The amoral or evil bishounen would turn out to be an important character type in later media, although in a rather different context.) Although Mari wrote for a general literary audience, her most ardent fans were women, and her works, along with Western films such as Maurice and My beautiful laundrette, began to create a female audience for highly-estheticized stories of male-male romance.

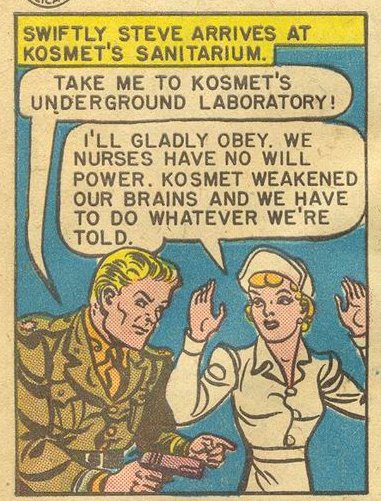

In the latter part of the decade, the newly-emergent category of shoujo manga embraced the bishounen esthetic as a natural correlate of its emphasis on cuteness and prettiness, especially with the influx of female authors in the mid-1960s, who brought a new emphasis on older (teenage, as opposed to pre-teen) readers, male characters, and sexual, rather than merely chastely romantic, relationships.[2] The rock-and-roll melodrama Fire! by Mizuno Hideko (1969) was the first shoujo manga with a male protagonist, as well as one of the first to include a sex scene (although an extremely discreet one).

Pages from the shoujo manga Fire! (© 1969 Mizuno Hideko) and Swan (© 1976 Kyoko Ariyoshi)

By the early 1970s, girl’s manga inevitably featured at least one luminous-eyed, tousle-haired young man with which the heroine could fall in love. Around that time, the new generation of female shoujo authors began to dispense with the heroine and have the boys fall in love with each other. Hagio Moto and Takemiya Keiko gave the world the first fully-fledged boys’ love manga, Takemiya in a number of schoolboy-in-love stories culminating in The poem of wind and trees (1976), Hagio in the faintly homoerotic The Poe clan (1972) and The heart of Thomas (1974) and eventually the much more explicit and brutal A cruel god reigns (1992).

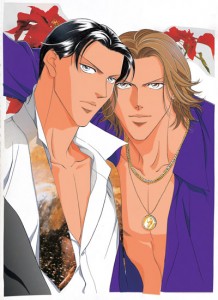

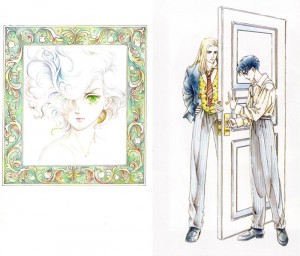

Gilbert from Poem of wind and trees (© 1976 Takemiya Keiko), Ian and Jeremy from A cruel god reigns (© 1992 Hagio Moto)

A cruel god reigns’s leads represent two different ways of making a modern manga bishounen. Jeremy, a younger teenager (16, at the start of the story), is physically more child-like: smaller, softer, rounder, with larger eyes. Ian (19) is closer to an adult but more deliberately androgynous: leggy and elegant, he wears his hair long, has a habit of tying his school tie in a floppy half-bow, and lets his girlfriend paint his toenails. In other words, Jeremy’s bishounen-hood is a product of his youth and boyishness, which in the context of the story emphasizes his vulnerability at the hands of his sexually abusive stepfather and a string of later predators. Ian’s beauty, conversely, is reinforced by gender-nonconforming traits, which don’t prevent him from taking the more active narrative role as he seeks, at various points in the story, to rescue, redeem or possess Jeremy.

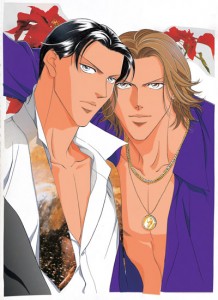

Strictly speaking, a guy is only a bishounen when he is a boy; once he is old enough to drink, if he is still pretty, he becomes a bidanshi, a beautiful man (biseinen is also understood but less common). Anglophone fans tend to loose this distinction, although they can dodge the issue with the contraction “bishie”. Which brings us to the third major way of making a manga prettyboy: the physically mature, more-or-less gender-conforming, but highly estheticized and idealized man, with glossier hair, softer skin, lusher lashes and more kissable lips than any botoxed-and-collagened Hollywood hopeful could hope for.

File under pandering, blatant (from Antique, directed by Min Gyu Dong, 2001)

The grown-up bishounen: Iwaki and Kato from Embracing Love (from the Kiss of Fire artbook, © 2004/2006 Nitta Youka)

Many commentators, both academic and amateur, have suggested that the appeal of the modern bishounen is that it makes it easier for the female audience to identify with the characters; that they are, in essence, women in drag. As Laura Miller has pointed out, those making this argument seem to have overlooked the popularity of real-life men who embody the bishounen esthetic. From Gackt to Johnny & Associates, pretty, pretty boys who are pretty make their handlers an awful lot of money from squeeing fangirls who probably aren’t thinking of them as their alternate self-image. In the late 1990s, the Korean movie industry woke up to the surprising fact that women buy movie tickets, and over the following decade reoriented their production from martial arts slugfests (with minimal dialog to facilitate international distribution) to luminous young men in soft-focus close-up, and did quite well by it.

The modern bishounen for men

From the 1940s until fairly recently, the bishounen and bidanshi have had a contested position in popular culture outside of that aimed at girls and women. One of the few places where he has been aceptable to the Y-chromosome-bearing masses is in the role of unspeakably evil villain. Osamu Tezuka’s MW (1976) was one of the first manga to feature this character type, in the form of a distractingly good-looking but utterly depraved protagonist-villain who rapes and murders his way through the contortions of the plot. Naoki Urasawa’s Monster (1994), possibly inspired by MW, has an even more beautiful but equally amoral young villain, who likewise uses his beauty to manipulate others in the service of his dastardly plans. The type makes good marketing sense: boys can hate him (’coz he’s evil!), and girls can slash him (’coz he’s hot!), and everybody’s happy.

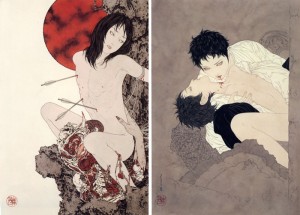

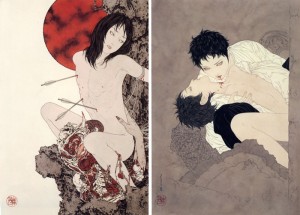

The other historic bastion of bishounen-hood is ero-guro, the surrealism-meets-shock-porn genre of “erotic grotesque nonsense”. All the way back in Edogawa Ranpo’s Ogre of the secret island (1929), we have a remarkably beautiful man (described as “bishounen” in the text despite being in his 20’s) who alternates between master detective helping the protagonist solve the murder of his fiancée and other mysteries, and potential villain with dark secrets of his own, including his unrequited homosexual love for the protagonist. Later writers in the genre agree that nothing goes with ethereal beauty and sexual ambiguity like gratuitous bloodsplatter.

Pretty boys and gore, two great tastes that taste great together (From Divertimento for a martyr, © 2006 Takato Yamamoto)

The place where impossibly pretty manga boys are really welcomed with open arms by the guys, however, is the gentle figure of the trap. In Western media, a man in a dress is either a hideous buffoon or a nasty joke about to be played on some unsuspecting and innocently horny straight guy. In Japan, however, putting a skirt on a bishie instantly converts him into a sort of Universal Fanservice Adapter, fawned over by fangirls and fanboys alike.

At the end of the day, however, the bishie has become the default depiction of an attractive guy in any Japanese media that hopes for any degree of female audience. As the entire manga industry becomes pervaded with shoujo styles (from the twin pressures of moe and attracting those sweet fangirl yen), the bishie is fast becoming the default depiction of an attractive guy, period. (Takeshi Obata does not mind drawing himself some pretty silken-haired boys, nosiree.) A few grumbles are still heard from those who like their square-jawed manly men in the old-school style, but the voice of the market has spoken: pretty is where it’s at. Gunslinging action hero or cupcake-baking romantic lead, bishiness comes loaded standard.

There is more porn of these three guys than the entire rest of the mangasphere combined (Guilty Gear XX © 2002 Arc System Works, Maria†Holic © 2006 Minari Endo, Happiness! © 2005 Windmill)

Footnotes:

1. Or from 5 to 13-to-20ish by modern age reckoning. Ages from Japanese sources are given as in the original. Traditionally, a child was considered one year old at birth and gained a year each following New Year; thus the given age is at least a year and up to two years older than the age we would ascribe. Back.

2. Although heterosexual romance as the culmination of the story had been a theme of shoujo stories since the inception of girl’s magazines in the 1920s, the love interest was generally introduced near the end of the story, as a reward for the heroine’s self-sacrifice and patient suffering; depictions of on-going romantic relationships tended to involve two girls – although their love was, of course, purely spiritual and nonsexual and would fade with the coming of adulthood in the form of marriage and motherhood. Back.