On the recommendation of Sharon Marcus, I recently watched The September Issue — a documentary about the making of the September 2007 issue of American Vogue.

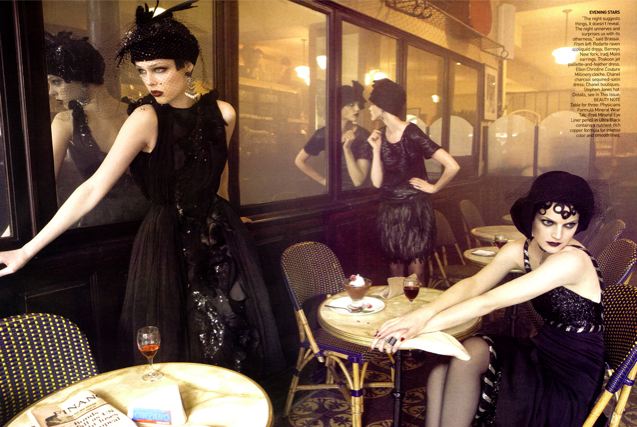

Ostensibly the film focuses on icy editor Anna Wintour, but as many reviewers have noted, the real star of the proceedings is stylist Grace Coddington, who tromps about the Vogue offices in flats and a shapeless black something, bird’s nest red hair flying off every which-a-way, mothering the models and midwifing gorgeous confections like this:

Just looking at that can send you into insulin shock.

Looking at it also made me think again about Stanley Cavell and his ontology of photograph. As I noted here a little bit back, Cavell argues that the borders of a photographs are arbitrary; the frame cuts out a square of the world, and in so doing implies the existence of everything else. A photograph is not a world; as he says, it’s part of the world. Thus it’s power is that it shows us that reality exists — while also pointing to the ways that we are cut off from it. We’re ghosts, unable to affect the world.

A world complete without me which is present to me is the world of my immortality. This is an importance of film — and a danger. It takes my life as my haunting of the world, either because I left it unloved (the Flying Dutchman) or because I left unfinished business (Hamlet). So there is reason for me to want the camera to deny the coherence of the world, it’s coherence as past: to deny that the world is complete without me. But there is equal reason to want it affirmed that the world is coherent without me. That is essential to what I want of immortality: nature’s survival of me. It will mean that the present judgment upon me is not yet the last.

As I noted before, this ontology seems to break down in the work of artists like Jeff Wall or Tarkovsky, which insist on the artificiality and contrivance of what’s within the frame. They do this to such an extent that they seem in some ways not to validate reality, but to call into question everything you don’t see. The picture is a world, and looking at it you wonder whether there is any other.

Something similar is going on in Coddington’s arrangement I think — though with a more pop inflection.

This is a deliberately created fantasy world; it’s referencing the 20s — but a faery 20s of languid, perfect glamour. The woman are obviously carefully posed — they aren’t arranged naturalistically, as if caught in conversation, but are instead placed about the stage set to display elegant limbs and voluptuous clothes to best advantage.

In fact, the models look less like people than like dolls. The image is affecting not because it gives us a window onto an uncontainable and undeniable real, a la Walker Evans, but precisely because it denies that real. This image is contained; the dolls and clothes and even the little dogs are available to the viewer for leisurely looking. There’s so much there — the ruffles on the dresses, the exquisite caps, the engravings on the columns, the food spread out on the blanket — but it’s a consumable plenitude, presented and arranged as an enfoldable opulence of desire.

This description dovetails nicely with why fashion photography, and fashion in general, tends not to be accepted as art. Art reaches for the deep and real; fashion for the shallow and artificial. Art causes us to appreciate our place in an wider and spiritual world; fashion packages trivial existence up as a capitalist fetish.

Yet, I wonder if the two are really that distinct.

That’s a Walker Evans photo. It’s obviously about reality; these people aren’t dolls dressed up by the photographer. The frame of the picture cuts out a bit of their world, but their world is not created by the frame.

And yet…well, here’s my reply to some comments made by Bert Stabler on the earlier post.

So you’re skeptical of Cavell’s whole effort to make art replace or equal reality — or else you think that he’s right that this is what film and photography claim, but you feel it’s ethically dubious, inasmuch as it elides the extent to which cropping does not point to the world but to itself; the boundary is the boundary of the subject imposed on the world. It’s modernist humanism; the individual becomes the measure of the world rather than vice versa.

Or, to put it another way, the ontological claim of Evans’ picture is more insistent than Coddington’s, but I don’t know that what he is doing is actually different in kind. You move around the picture noting details, patterns, textures — lines on faces instead of ruffles on dresses, a penis instead of a bulldog, perhaps, but still details that become yours. Perhaps the real difference is that for Coddington what you own is a fantasy, while here you own reality itself. Or, maybe in Coddington the picture’s reality is hidden beneath the finery of fantasy, while in Evans the picture’s fictitiousness is concealed by the distracting nakedness of reality.

If there is a reality in Coddington’s piece, that reality may be Coddington herself — or the part of Coddington in the picture, which is her desire. Where Cavell sees the picture as reality and the observers as ghosts desiring but unable to get in, Coddington’s images are themselves frozen shadows, locked in place while the viewer moves over and through them.

The two women in the front are stiff and gazing away from each other, suggesting an unspoken (sexual? romantic?) tension, perhaps between one another, perhaps aimed at someone (a man? a woman?) just out of view. There is a world beyond the frame, but it is defined not by the border but by the gaze, and it does not by any means exclude the viewer, who may in fact be its object. In case someone somehow missed that point, Coddington has helpfully included some mirrors to gratuitously display for us, the audience, Coco Rocha’s shapely shoulder as well as to allow the woman in the back to gaze raptly at herself, almost close enough to kiss her own image.

The women looking at this picture (and within this picture) are not, then, powerless spirits forced to acknowledge the world’s coherence without them. Instead, they’re active participants; the world is there for their gaze, their identification, and their desire. The image is there so you can touch the dresses and touch the woman, inhabit the dresses and inhabit the women, play with the dolls and imagine being the doll that is played with. The being that is in this picture is not in the frame that cuts out and signals reality. Rather, it’s in the desire that inhabits the subject viewing and the object viewed and blurs the lines between them.

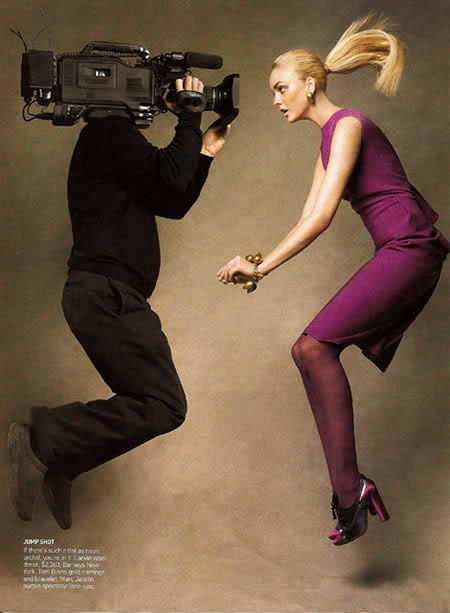

In one photoshoot in the September 2007 issue of Vogue, Coddington actually played quite consciously with the ontological difference between fashion photography and more documentary approaches.

The cameraman jumping there is a real cameraman; it’s the guy who shot the “September Issue” documentary. After he’d been following her around for weeks, Coddington asked him to appear in the shoot at the last minute. The documentary then showed how the Vogue staff took the image of the cameraman, took the image of the jumping model, photoshopped them together, and thus created the illusion of the documentarian filming the model leaping together in n-space.

Further, the documentary covers the disagreement between Ana Wintour and Coddington over whether to photoshop the jumping cameraman. Wintour wants to take out his gut (“You need to spend more time at the gym” she tells him.) But Coddington insists that he doesn’t need to be photoshopped. “Not everything’s perfect in this world,” she says. “It’s enough for the models to be perfect.” (As you see, Coddington won; he’s still got a gut.)

The documentary itself is intended to show the (somewhat ugly) reality behind the beautiful world of fashion — cover-girl Sienna Miller’s ratty hair, the tension between Anna Wintour and Coddington, etc. etc. And Coddington responds by putting the documentary-maker in her image, serving as an icon for the reality which he traffics in. His paunch stays — but it stays as part of an image which is ostentatiously goofy, not gritty, and which is in any case quite clearly impossible.

If the documentary is going to reveal the “real” Grace, Grace is going to turn around and conceal the “real” documentarian. Face covered, he is no longer a truth-teller, but an instrument of glamour, impossibly suspended as he looks with and for Coddington at the perfection of the model. Female readers of the magazine (who perhaps have slight paunches of their own) are like the photographer looking at the model while also imagining being looked at like her in a frame that encloses and excludes nothing but the looking and the being looked at. Ontology’s not an inescapable truth, but a tease and a friendly in-joke. Don’t trap it in a frame; make it jump for you.

I really enjoyed this essay.

I have a hard time accepting that photography is, as a genre, art, but I think the closest it gets is fashion photography. It’s funny you mention spirituality, which I think that fashion photography often addresses. There’s several Zink spreads that are very spiritual–I should try to scan in the one with the masks sometime, except my scanner is ded. Have you seen that great Last Supper done with the redheaded fetish models? I think it’s under water. One of my favorites. That’s a book, not a magazine, but still. It’s pretty great.

Thanks!

I haven’t seen the Last Supper spread. My knowledge of fashion photography is really limited, though I find it interesting.

The spirituality is hard to sell when it’s all in the context of selling clothes…yet, on the other hand, why not?

Are you down on art photography, VM? My dear friend Bert loathes art photography; he’s got a great essay about it here. He ends the essay by arguing that

“Sherman and Opie signify the intention to bestow phallic power on themselves and their subjects by using photographs as wordless statements, staged and intentional semi-enunciations, sentences needing to be finished. The identities of the subjects can perhaps, through force of will, occasionally merge slightly with the viewer instead of melting before his eyes. Perhaps this is the best a narcissistic medium can do.”

So the one kind of art photography he’s willing to countenance (more or less) are staged and intentional semi-enuciation connected to femininity and the play of identity between viewer and subject. Which sounds a lot like fashion photography.

I recently watched an episode of American Masters called Alfred Steiglitz: the Eloquent Eye about photography-as-art that was really superb.

I think representational photography faces some of the same challenges as other forms of representational art — I have a hard time thinking of a straightforward landscape painting as “art” too. In fashion, there’s an inherent artificiality — sometimes and embrace of camp, but even the fashion notion of “beauty” is highly stylized — so even when it’s representational I think it has access to some of the things we associate with abstraction, and therefore with art.

It is a good essay – I’m right keen that fashion is now a Thing this blog does!

Well…it’s a Thing this week anyway! I’ll probably be distracted by some other shiny thing soon enough….

Greatest essay on photography is Roland Barthes’ “The Great Family of Man” (read it in Mythologies!) on the exhibition of the same name. The notion of “representing reality” pretty much goes out the window at that point.

Ha! Yes, actually when we were at Earwax, Bert and I had a short discussion about art photography. I was so relieved to find someone else who doesn’t find art photography to be, well, art.

The Last Supper is done by Howard Schatz I think. I can’t remember which book it’s in, he has several (H20, Water Dance, etc). He’s a big fan of redheads and has a book specifically about them, but he also photographs nudes and various body types. Really great stuff.

I should go read that essay by Bert.

Say, Caro, I ran across this completely random representational art today and was struck by how moving I found it: http://www.artistaday.com/?p=6026

Apropos of nothing really. Just thought it was haunting and I’m not sure why.

I don’t know, I like Cindy Sherman…

BTW, I was a child model. Appeared in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, McCall’s, Life…

Alex, I rarely know who the photographers are since I’m too busy staring at the shiny. I know Shatz because my brother has his books. Otherwise, I’m a fan of the European fashion mags, and ogle them nearly exclusively (except for Zink).

That’s wild about the modeling. There are almost no photos of me in existence.

Bert likes Sherman too! She’s the exception. (I like her as well.)

My ears were burning! And thankfully I didn’t have ear flu.

Nazis are always my favorite paradigmatic exception, aren’t they yours? Right, so Nazism is the most disagreeable political agenda imaginable– which for some (like Zizek) makes it not somehow “real” politics. Pshaw.

But Zizek says also that reality is what pushes back. And a synonym for “pushes back” is “repulses.” Which is illuminating both for the status of fine art photography as “real” fine art (it most certainly is fine art– contemporary photography takes up more journal space and market space than perhaps any other single medium) and for why it is so egregiously dysfunctional. A photograph is an image that, while it cannot push back, can’t handle being just an image. And while other virtual media have far more power culturally (TV and movies, video games, blah blah…) they just can’t assert the level of uncanny reality that a photograph can.

Which is why the documentary photographer (and the documentary filmmaker in her wake) has had the odious zeal of a colonial missionary (another nice homo sacer archetype) or the modern equivalent– the anthropologist, teacher, or social worker– because of a claim to authority that is based on truth (verisimilitude), and a claim to truth based on authority (fine art) that are obviously not consistent with proper claims to truth and authority, but merely support each other with a bunch of mumbling about authenticity and grittiness.

But I’m right that fashion photography doesn’t set off your repulsive authenticity gag reflex, right? Or at least, I know you’ll agree that Grace Coddington is cooler than Walker Evans. (Best to set the bar low….)

Oh right– sure! It’s kind of like illustration.

There’s bad inauthentic art photography too. Anyone know Sandy Skoglund? Beloved by art teachers everywhere…

Out of curiosity, has anyone here read Ariella Budick? She’s a critic for the Financial Times and specializes in art photography.

I have no idea whether she’s good or not. It’s just that I briefly knew her years ago and recently found out about her career.

Noah, have you thought of having a roundtable on shiny European fashion magazines? It would be awesome!

I just looked at her mean thing on Marina Abramovic, which was funny. “Like Jesus, she wants to suffer for humanity. Like a porn star, she wants us to watch.” She also made sure to imply that Abramovic’s former partner dumped her, not the other way around.

Oh, that was a response to Tom, by the way. Also by the way, I do approve of performance art, but I also approve of snark.

Yikes, she has changed.

It’s worth looking at the rest of Cindy Sherman’s “generation”– Richard Prince, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, all those appropriators. It was a worthy effort. As are Ed Ruscha’s photos of parking lots. But it all feels like they’re trying to find a way to make cardboard taste good.

Although, did you all hear about Nicki Minaj ripping off former Warhol sidekick David La Chappelle?

Warhol is worth talking about. Certainly more than John Baldessari or whoever. I really admire Warhol as a self-aware impresario, but, boy, he really knew that he was pouring chocolate syrup on cardboard.

She ripped him off how?

So…autobio comics. Similar issues with photography?

oops, no, it was Rihanna. That actually sort of makes more sense. Here’s a link: http://www.mwza.com/rihanna-sued-by-david-lachapelle-over-sm-video/

Autobio-comics-comparison-wise, yes, kind of, in regards to all of the mundane specialness that is really just mundane. While combining confessional lit-fic with superheroes is sort of its own thing, and combining painting and photojournalism is sort of its own thing, autobio comics and art photography try to imbue a popular medium with gravitas and end up only escaping their navel by referencing the rather non-magnificent history of the medium.

Yeah. Or don’t escape their navel while referencing the non-magnificent history of the medium.

That Rihanna song is pretty lame. I keep hoping she’ll start making decent music again, but it doesn’t seem like it’s going to happen….

I’m a big fan of the Raining Men song she does with Nicki, actually.

I’m deeply confused by what you guys are classifying as art photography in your criticisms, because at the moment it seems to be either ‘anything I don’t like’, or ‘that one artist I actually know about’. At the moment, there’s an embarassing amount of ignorance and shallow dismissal going around for a bunch of people with pretences of being critics.

Bert Stabler, knows a ton about art photography. You could click through the link above to read his essay about it. Or just cultivate your indignation, whichever you prefer.

Nice to have someone offended on behalf of art photography though. Normally we only get people offended on behalf of comics.

Oh lordie I just wrote up a 5 paragraph rebuttal to your friend’s article and then forgot to fill in the captcha, I might cry, maybe I’ll rewrite it when it isn’t 3am.

Right now suffice to say I did read his article and already had when I posted the first comment and don’t appreciate the passive aggressive patronising implication that I hadn’t.

It seems you personally actually dislike one very specific and commercially succesful subset of art photography, the contrived and voyeuristic documentary with pretenses of authenticity. Surely you don’t think that constitutes the entirety of art photography do you? Unless you have a very different definition of art photography than my definition, which is why I asked you to clarify it

Argh. Sorry about the captcha; I know that’s horrible. The best thing to do is to create an account on the upper right. If you’re signed in the captcha won’t bother you.

Alternately…if you’d like I’d possibly be interested in running your piece as a post on the blog. If that sounds appealing you can email me; noahberlatsky at gmail.

Re: me and art photography. I think you’ve misunderstood where I’m coming from. I don’t really have a hardcore dislike of art photography. I’m not as knowledgeable as Bert (who is very knowledgeable), but from that limited knowledge I probably like it overall more than he does. I don’t think I made any sweeping denunciations of it either in the piece or in comments? I didn’t mean to anyway. I don’t really have a dog in the fight, is what I’m saying. If you want to like art photography it’s fine with me!

Ah sorry about that, I think I got some of the other commenters mixed up with your comments. I wouldn’t mind writing a semi-rebuttal for the blog at all, or at least a piece on some really interesting art photographers.

Marcus, Was it me? I don’t hate all of it, but to me a lot of it isn’t art. For instance, a war correspondent’s pictures move me, yes, but they’re documentary, not a vision that came from the artist. As such, I see those photographers as scholars, recorders, not so much creators. The idea that they have created what they are depicting is…exploitive at best.

I don’t read stuff like Zizek, I just go to art galleries (or books, art mags, deviantart, etc) and look at stuff. Sometimes I see art photography that works as a vision of the creator, but mostly, no. Euro fashion photography, much more so. I’m an artist in my own small way, and I usually make up my own mind about stuff without bothering to read up on formal criticism, so I rarely talk about it in the er, more formal way my colleagues here do. I just don’t find most of the photography exhibits moving as art. Not all of it, mind you, but most of it.

VM, do you like the Jeff Wall photograph in the post? It’s pretty stagey…and probably was deliberately staged….

The one with the mattress? No, not really. It feels fake, but not in a good way (not in a way with an interesting take on the world, anyway). It doesn’t resemble the real torn up worlds that I’ve seen, for instance.

Yeah, I really dig the fakeness of it. It’s like a still life (Bert’s claim of painterliness) but it’s also sneering at a kind of fetishization of the real, I think. And it’s sneering at still lives too.

I just love how bitchy and mean Jeff Wall is in general. All his pictures just seem to be sayin, “fuck you.” I really appreciate that about him….

Yeah, I feel pretty much the opposite, because to me it screams “I am an art school dude, see me rip apart a mattress, watch me be EDGY!” I just want to roll my eyes and tell him to buy a black turtleneck already. Heh. And I don’t like the composition, either, and I feel the pretty hat just makes it all seem like he’s trying to stage an angry girlfriend leaving him (or someone), but it looks more like a second grader’s social studies diarama.

That’s interesting about the hat…I just feel it’s so obviously arranged, I don’t feel any impulse to try to create a narrative for it. And I like the messiness of the composition; the sense that he’s carefully put together a junkpile. And I really like the colors.

He’s a really controversial artist though. Lots of people hate him.

Well, the colors are kind of pretty, but I think it’s got a lot of narrative in there.

It’s kind of a classic spiral composition, and moving through it, you’ve got the female dancer, the walls painted red (romance), the mattress (bed, sex) that’s torn, the piles of women’s sundresses, the hat, and a pair of black stilletos (sex if I’ve ever seen it in iconography) one tipped over, one not. I dunno. None of them are particularly interesting images, but they do say narrative to me.

I like your reading; I hadn’t really paid attention to the narrative elements. I feel like they’re probably there to be denigrated or as a kind of trick more than as an actual effort to construct a story…but I can see where you’re coming from as well.

‘Marcus, Was it me? I don’t hate all of it, but to me a lot of it isn’t art.’

Why? What do you define as art? Because to me a basic understanding of late modernist and contemporary art is understanding that anything can and should be art. Art isn’t a qualitative measure, we should accept art as the broad definition it is and instead specifically judge works on what they have to say.

‘For instance, a war correspondent’s pictures move me, yes, but they’re documentary, not a vision that came from the artist. As such, I see those photographers as scholars, recorders, not so much creators. The idea that they have created what they are depicting is…exploitive at best.’

Most art does not stem entirely from the vision of the artist but instead reflects upon a reality that already is. Every photograph taken is an incredible amount of aesthetic choice and thus, creation, from the intuitive choice of framing to the conceptual basis of the work to the choice of aperture, shutter speed, iso, lens, post production experience, presentation of the work etc.

The idea that photographic art is simply pressing a button and presenting what was there without any aesthetic or creative intervention is a fallacy.

Art has been made of card index files, short statements on paper, thoughts spread among other people, thoughts held in the mind,gases released, passive observations of phenomena, even doing almost nothing at all (see Francis Alys’ ‘sometimes doing nothing leads to something’). All of these works have incorporated artists as scholars, recorders, archivers and interpreters, because in the end, that’s what an artist really is, an interpreter.

Frankly, any art that claims to have sprung entirely from its creatore without the effect of other agents is probably intensely narcissistic and boring, even Blake claimed the intervention of heaven.

Also noone in art school wears black turtlenecks anymore, it’s all flannel and hats round here.

Noah : “The two women in the front are stiff and gazing away from each other, suggesting an unspoken (sexual? romantic?) tension, perhaps between one another, perhaps aimed at someone (a man? a woman?) just out of view.”

While I find your interpretation of the image compelling, I’d like to throw another angle into the equation: Eve K. Sedgwick talks about the triangular formula in which male rivals for a female are in fact masking homosocial interest for each other. It made me think that here, the tension is that of a triangle, which as rightly observe is shown in palpable frisson of disinterest in the two women in the foreground. The provocative idea is confirmed by the women in the backgound who looks at herself in the mirror. Her gaze is directed into the mirror at herself might be seen as a reclamation of personal power. It further eroticizes this intriguing image.

I consider images of this kind(high end vogue)to be art. I see all art as part of the machinery of capitalism…not always totally evil. Realism and documentary are to me extremely murky, with respect to plausibility (vraisembleable)and truth (verite), since I am the receiver of these images and on some disgusting level, I am aware of how far I can distort reality myself.

I think it’s definitely playing with/disavowing/avowing a lesbian subtext, both between the models and between the models and the viewer. Is that what you’re getting at to some extent?

Apologies for the typos,

the unclear passages should read :

“which as Noah rightly observes”

Her gaze is directed into the mirror, at herself,which might be seen as a reclamation of personal power.

Yes,and, it is a reformulation of the typically male centric triangle, but here as I said, where the two girls (foreground) are made rivals for the “girl”. We might push it past the lesbian into a usurpation of male power, a play on that narrative. The traditional narrative is restructured. Proust played with this typical structure and set up St Loup and Marcel and “the girl” and then rendered it A typical by revealing homosexual identity of St.Loup.(Sodom and Gomorrah).

Of course, it is possible I am just reveling in the kaleidoscopic possibilities that that the image allows,precisely because it is seductive to a female viewer as it mimics the familiar, safe love triangle of the romance novel. However, once inside the image, gender is confused and then slips wonderfully out of the control of that romantic narrative structure.

Well, Sharon Marcus talks about Victorian fashion imagery as designed specifically to allow women to fetishize and commodify other women, allowing them to occupy the position of male (but now not male) mastery. This female-desiring-female wasn’t really lesbian for the Victorians; it was a part of heterosexual identity. I think that’s still kind of true, though obviously we’re more aware of lesbianism as an identity than I think they were.