I wrote a piece on women’s magazines recently over at the Atlantic. While I was working on it, it occurred to me that fashion editorials are basically as series of images, linked by themes or characters. Which is to say, they are, in some sense, comics.

You can take that “in some sense” there more or less seriously, as you wish. Personally, I”m not necessarily all that interested in trying to figure out what does or does not qualify as a comic. I thought it might be interesting, though, to look at a fashion editorial from the perspective of comics, and vice versa, and see what the similarities and differences say about one or the other or both.

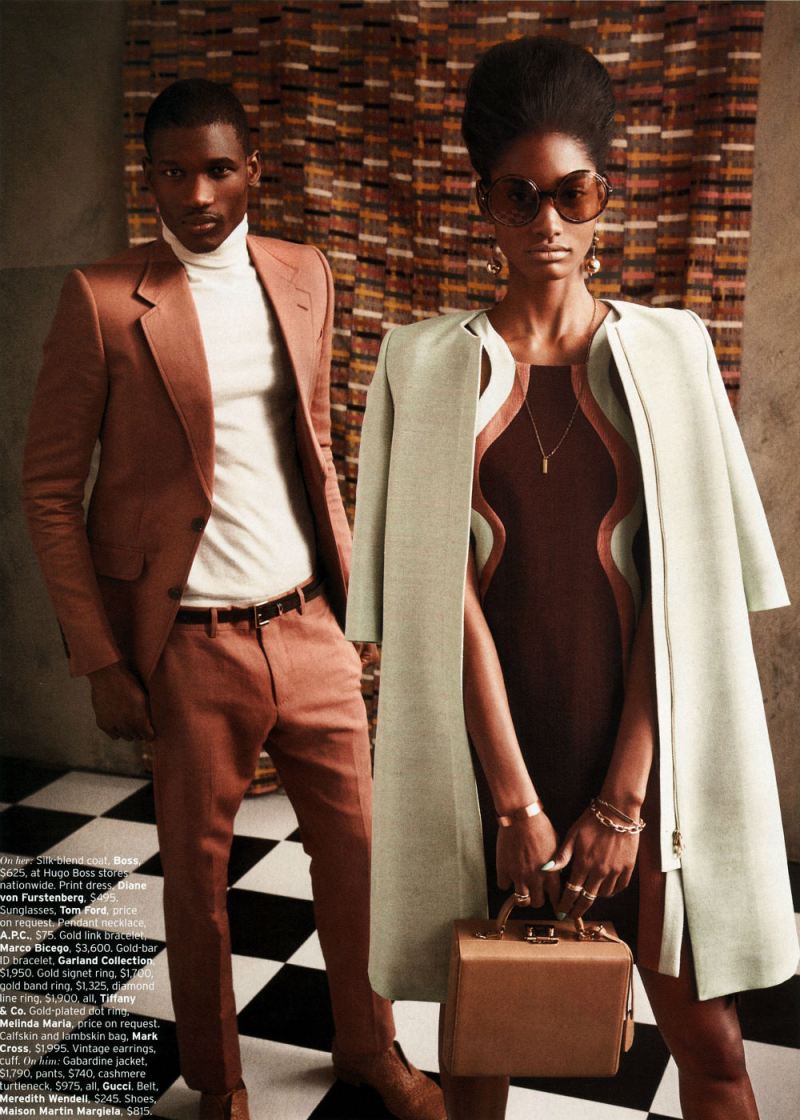

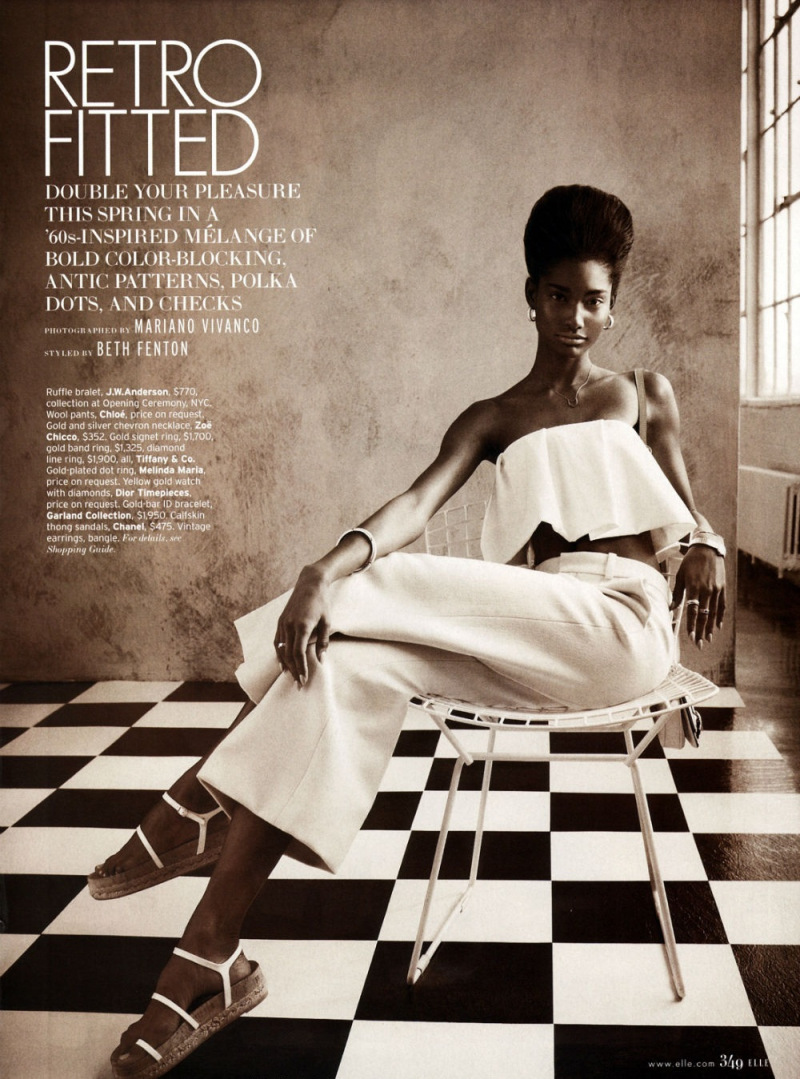

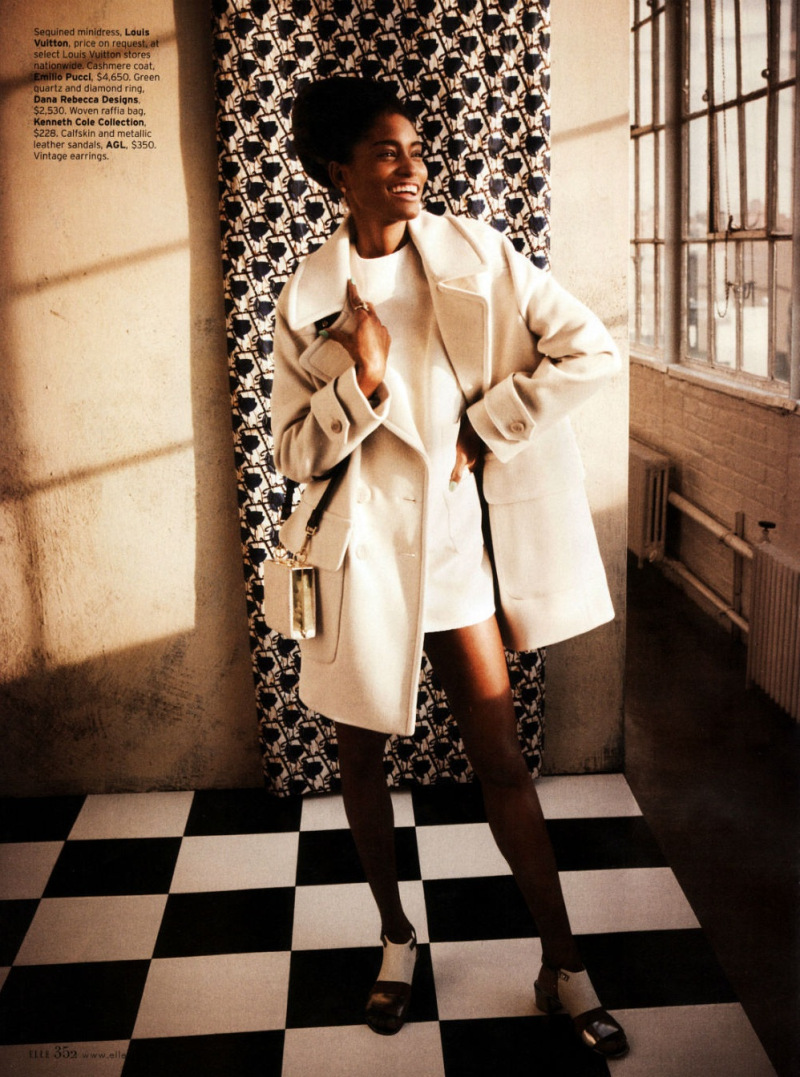

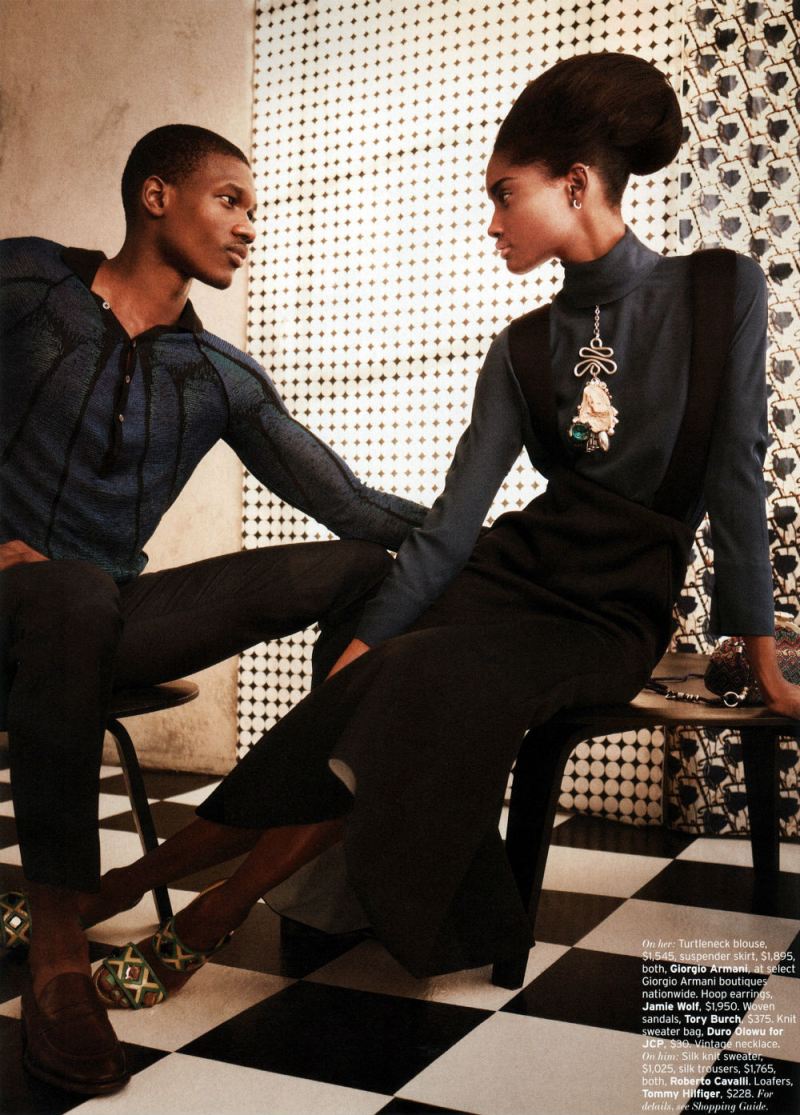

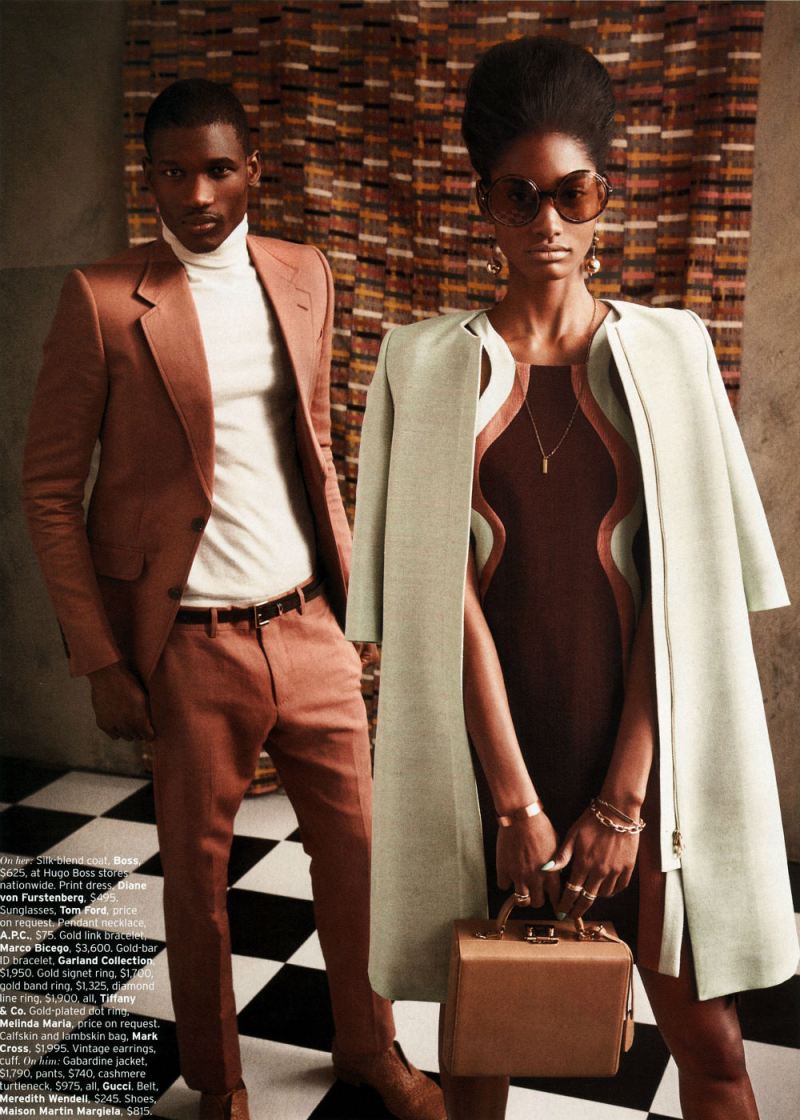

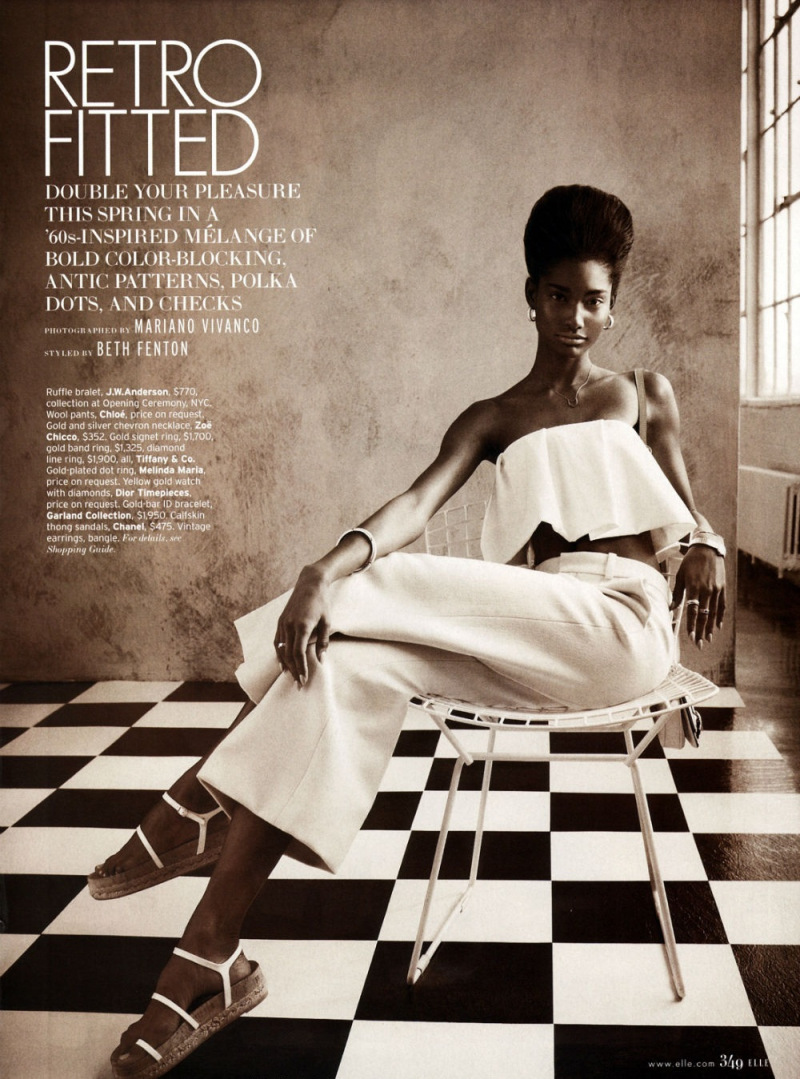

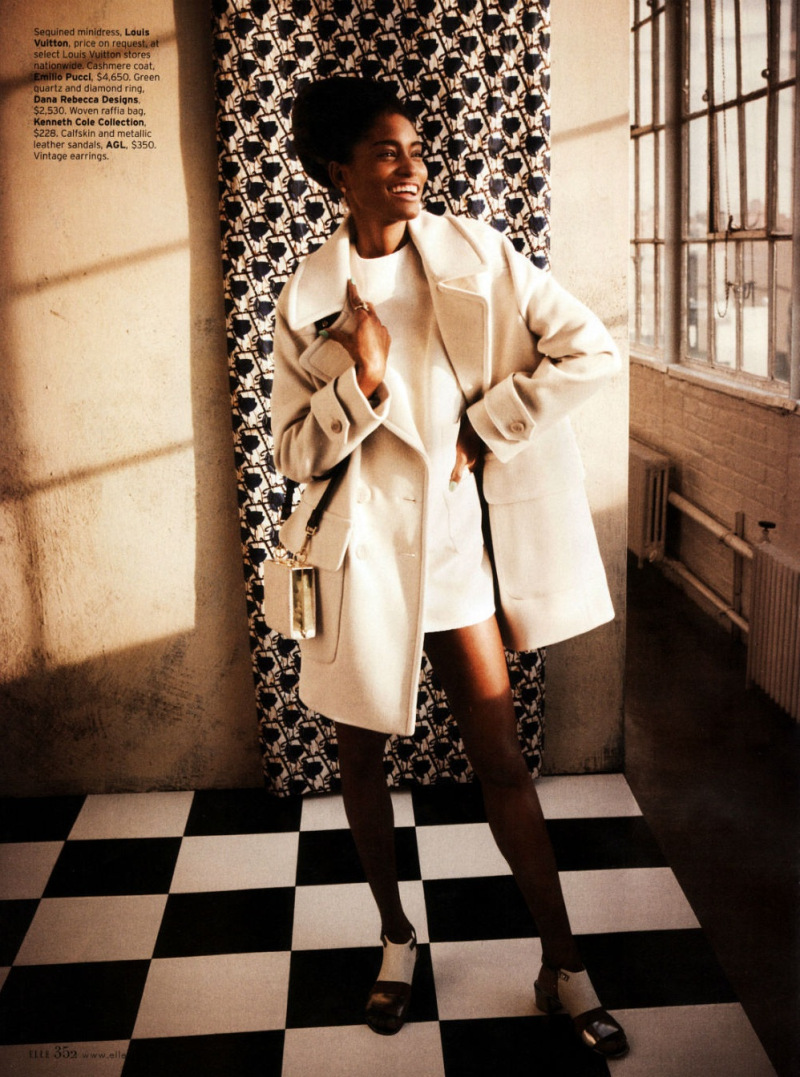

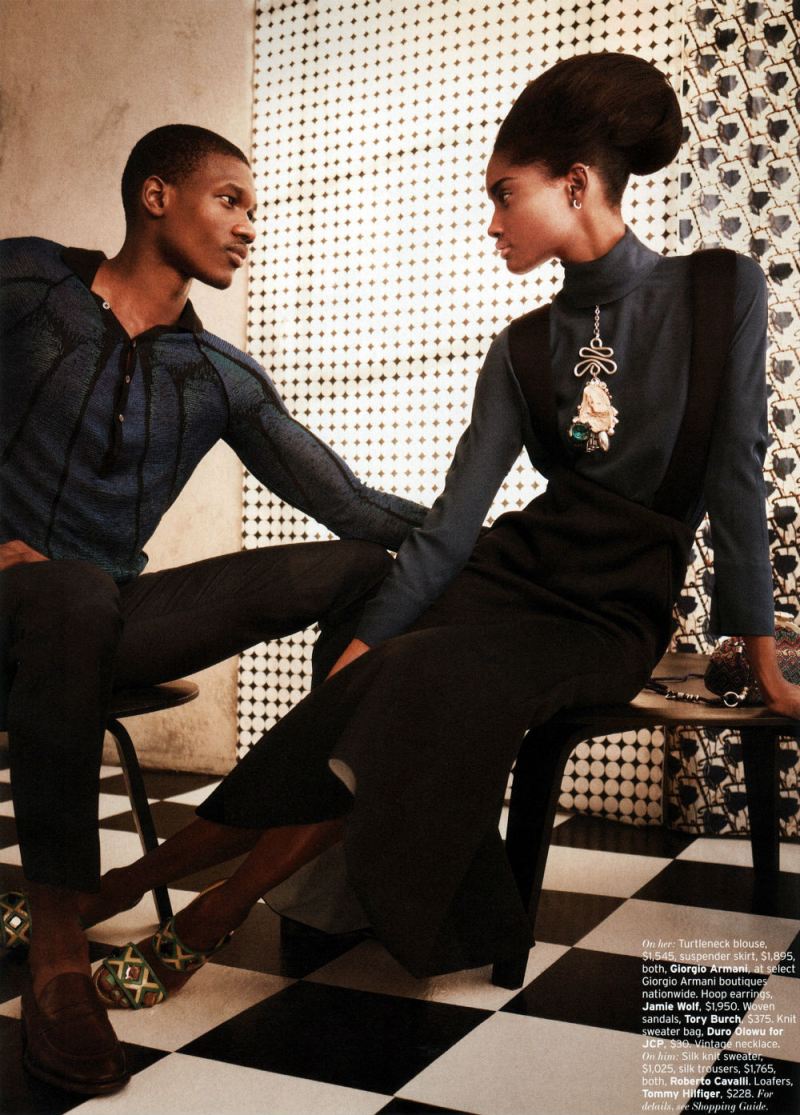

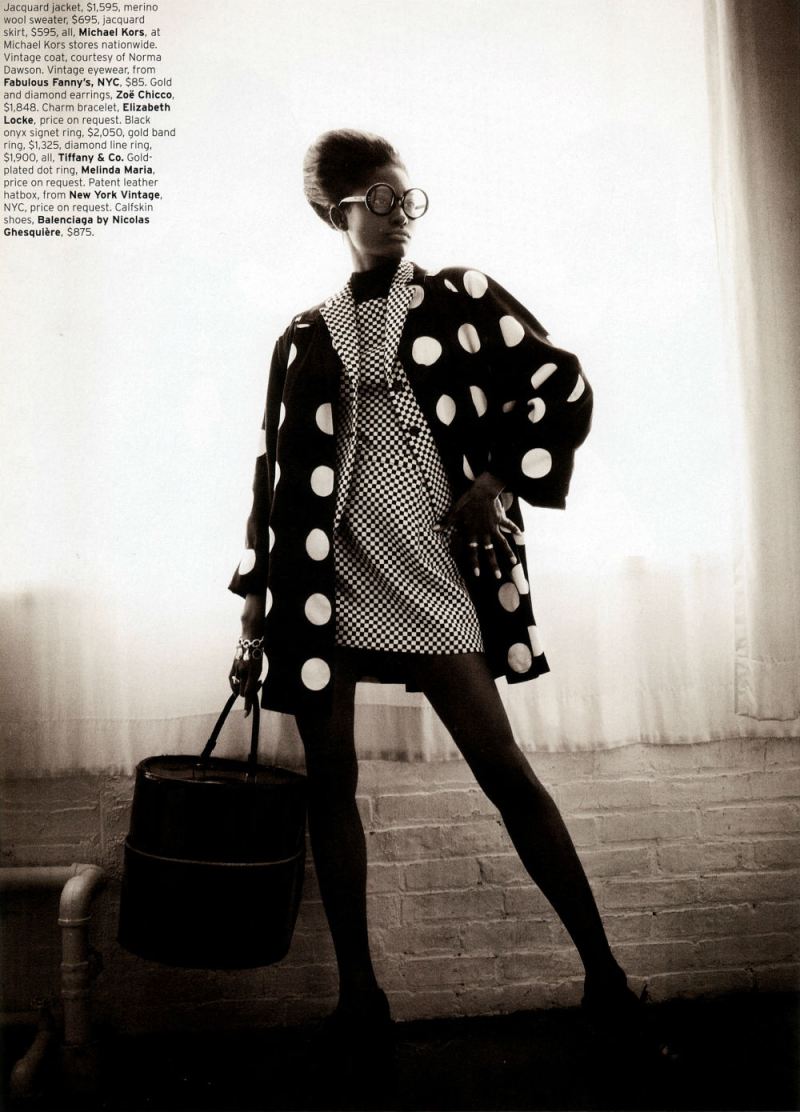

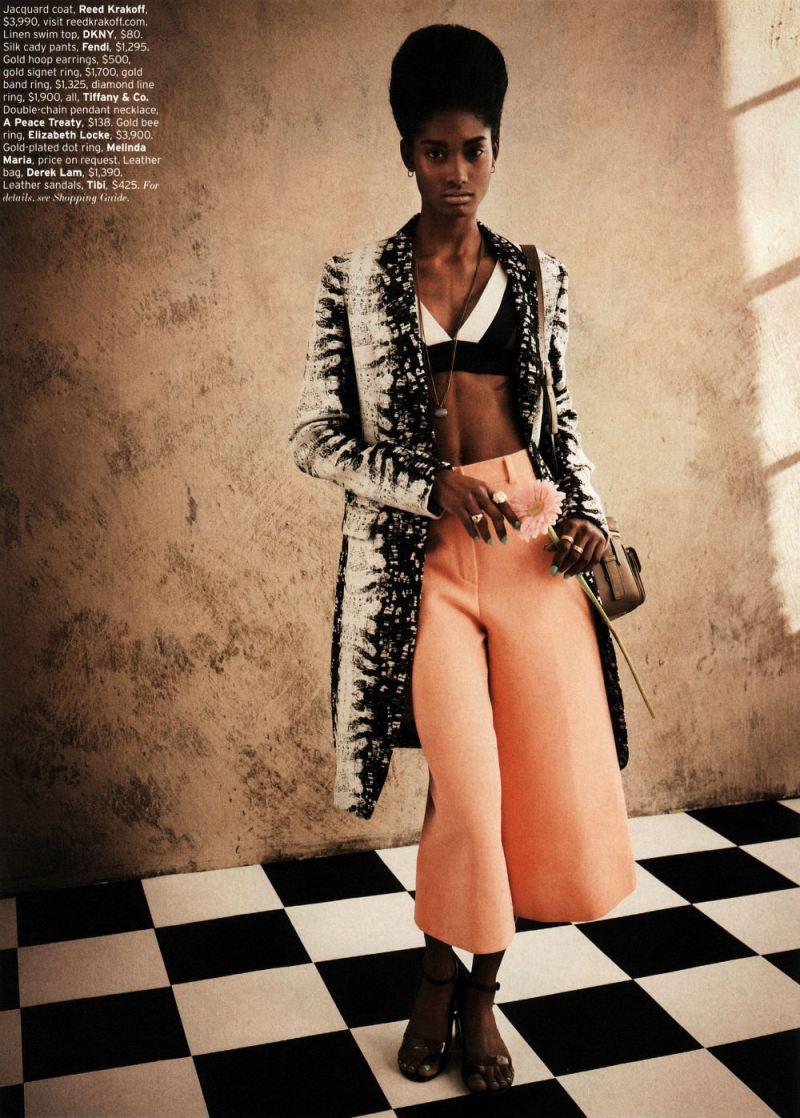

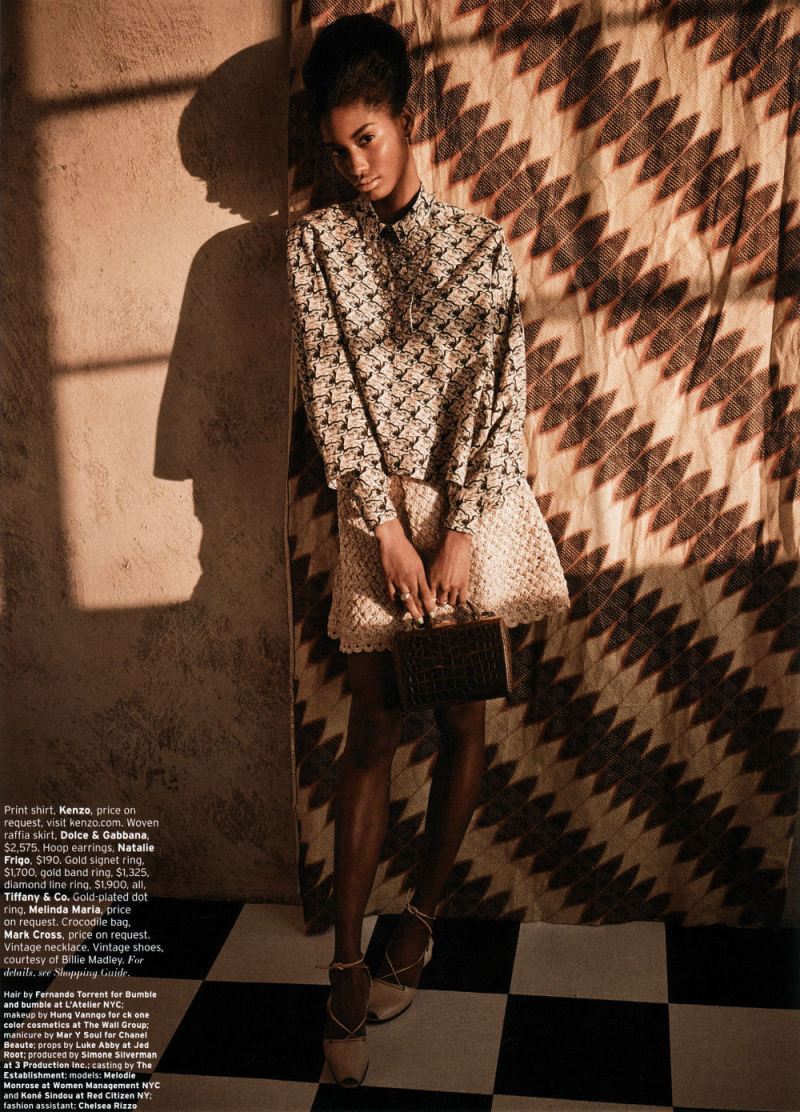

So, somewhat at random, and somewhat because I like it, I decided to talk specifically about Retro-fitted, an editorial in the April issue of Elle. I’ll be posting the images below, but you can see the entire thing at this link. The female model is Melody Monrose; the male model is Koné Sindou; the photographer is Mariano Vivanco, and the stylist is Beth Fenton.

This is going to be in the nature of brainstorming rather than thesis and argument…so I’ve separated it into some subtopics, and we’ll see how it goes.

Splash Pages

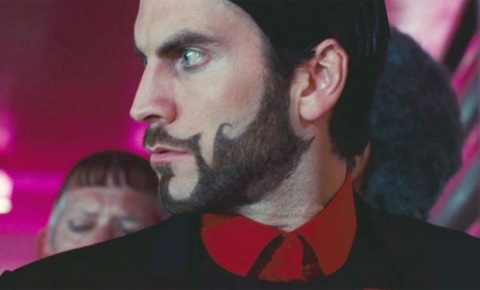

In a post last month, Kailyn Kent pointed talked about the way in which comics both fetishizes and can be nervous about splash pages. Kailyn linked this to the fact that the splash pages’ monumentality, and its focus on a single image, tends to replicate the look and experience of gallery art. Comics, then, likes splash pages because they suggest high status and seriousness. At the same time, creators like Chris Ware, attuned to the gallery scene and comics’ relation to it, sometimes seem uncomfortable with the splash page, or try to undermine it, precisely to turn away from its gallery connotations, or reassert comics comicsness.

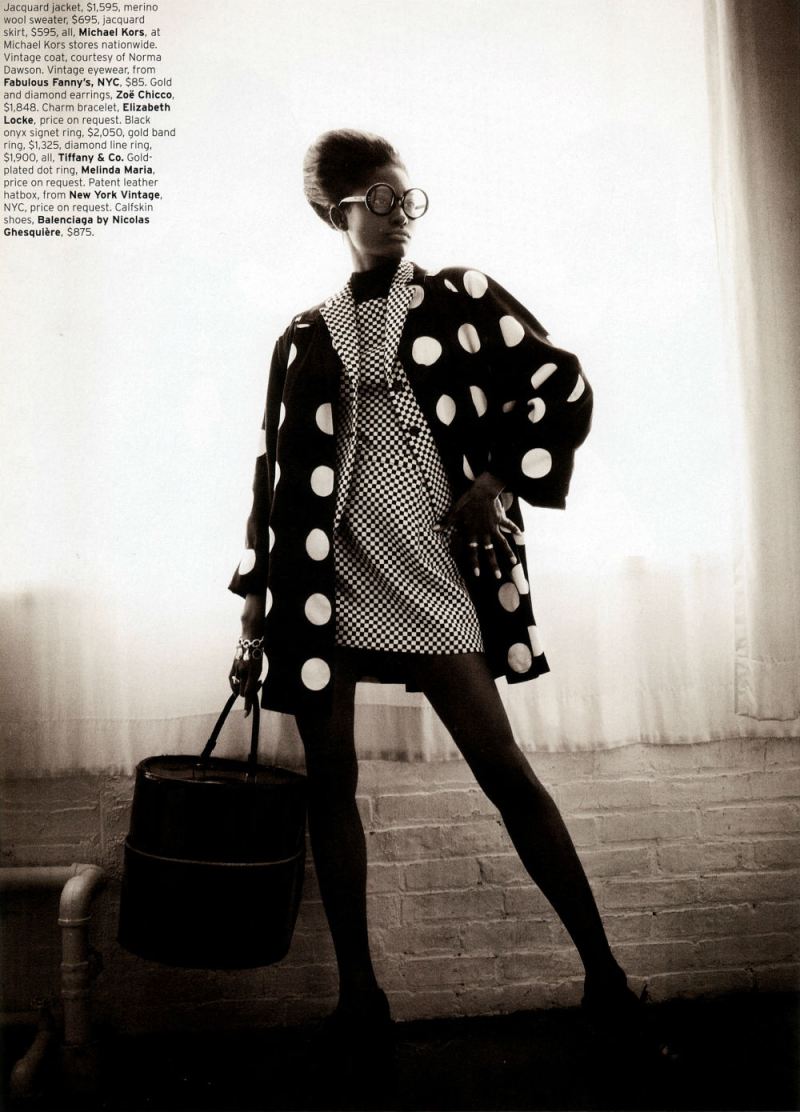

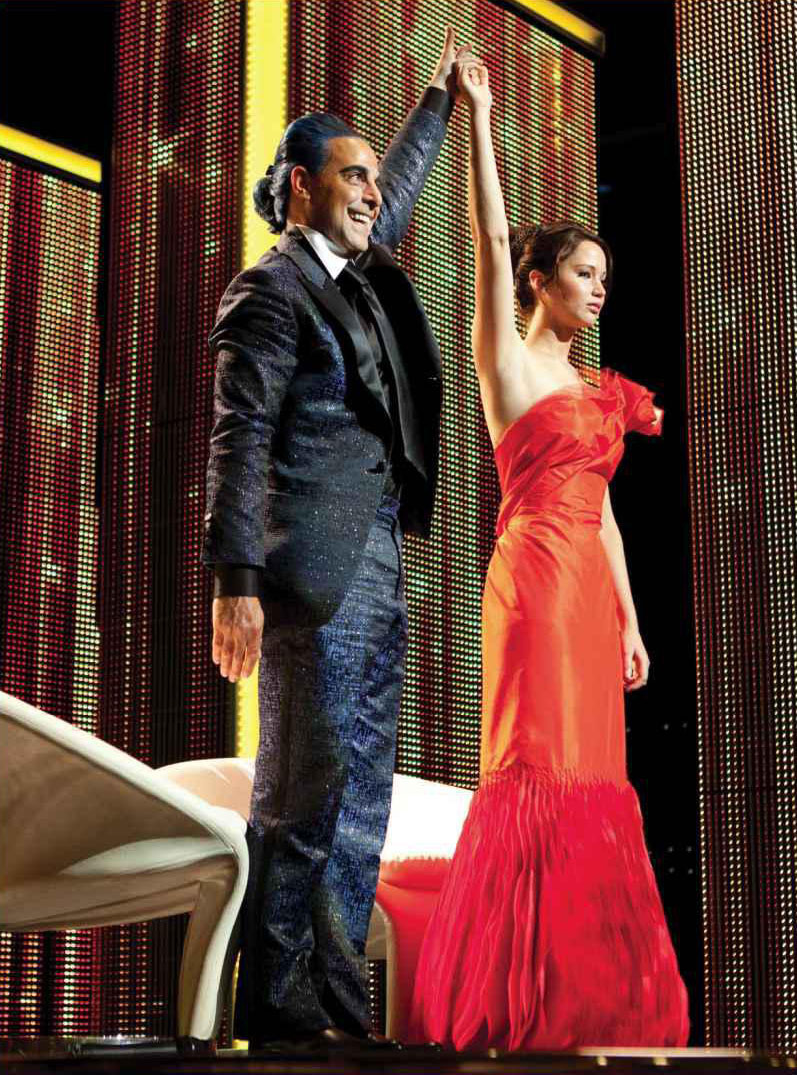

As this suggests, though, there are other possible contexts for splash pages. Obviously, this page, with the title and credits positioned dramatically off to the side in the image’s negative space, strongly recalls title pages from comics. But really most images in fashion editorials — taking up as they do the entire page — would qualify as splace pages in comics.

Splash pages, then, recall, not just fine art, but advertising — which could arguably turn Kailyn’s analysis on its head. Splash pages could be, not upmarket, but down, connoting, not seriousness, but gaudy commodification — as, perhaps, attested by the fact that splash pages are often the most high-priced pages on the comics art market.

If monumentality is a sign of trash rather than class, that could in turn explain why high-quality literary comics like Maus or Persepolis prefer small black and white images and few, if any, splash pages. Part of the literariness, and of the highbrow credibility, is avoiding comics’ links to advertising’s garish boldness and drama.

I don’t think that Kailyn’s analysis and mine have to be exclusive — especially since fashion photography has its own complicated relationship with high art. But it does seem worth thinking about the ways in which the dialogue between comics and art isn’t always, or doesn’t always have to be, a dialogue. There may be other voices speaking.

Fashion of the Literaries

Oue recent roundtable talked about whether comics should be seen in relation to the literary or not. This ends up also being a debate about whether comics should be seen, or judged, as high art — with literary and narrative qualities seen as highbrow standards, and comicness being seen as evading them through the lowbrow energy of the image.

How do fashion editorials fit into that debate? Confusedly, since, while there are series of images, and perhaps even characters, there is generally not narrative. If comics’ essence is non-literary, then, it seems like in some sense fashion editorials might be seen as more essentially comics than comics themselves.

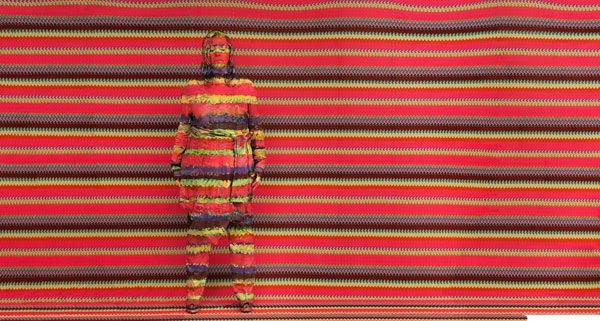

Part of that essential comicness, you could argue, is the way the images push away from meaning or language towards abstraction. In the tradition of Whistler’s Mother, perhaps, the woman in the image seems to be less there for herself than as an exercise in a musical distribution of space — the checked tile floor (a motif throughout the editorial), the broad vertical stripes of the dress, the grid of the chairback, the tight horizontal stripes of her sweater, carefully posed casual position, mirroring the chairs’ stiff curve, and the way she’s dramatically pushed off to one side. The patterns and the composition, are more important than what is being shown; she’s a surface rather than a body.

The body is surely important as well, though — as, for that matter, are the words, which may not tell a story, but do label the image, telling you price points for each not-surface-but-thing. The models position — head down, hand cupping her chin with the fingers almost shielding her face, suggests, perhaps, a kind of embarrassment at the crass commerce floating in white text over there on the wall. If writing is literary, then the literary here is not highbrow; rather it is distinctly low-culture. No matter how the image looks optimistically towards art, the words float leadenly behind it, staining abstraction with the nattering economics of signification.

What Are You Looking At?

Fashion photography presents bodies to be looked at. Those looking at the bodies are generally women…and the bodies looked at are, also, generally women.

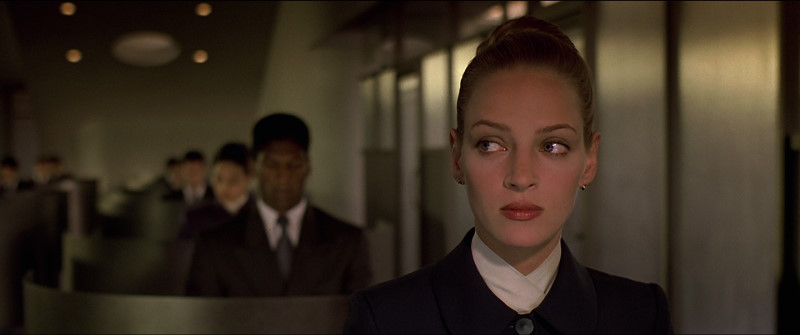

The image above — with a man and a woman looking at each other, doesn’t so much change this dynamic as underline it. The man looks at the woman with intense, romantic interest, just as the reader of the editorial has been looking at this same woman with romantic interest. The woman looks at the man with intense romantic interest — just as the reader of the editorial has been gazing with intense romantic interest. The fact that the mutual inter-gender erotic gaze is meant to accentuate, rather than supplant, the same-gender erotic gaze is emphasized by the strongest visual element of the picture — the almost comically dramatic, borderline yonic necklace dangling down the women’s front.

If the female gaze is eroticized in women’s magazines devoted to women’s bodies, it seems reasonable to suggest that the male gaze may be eroticized in magazines devoted to male bodies. “Men’s magazines devoted to male bodies” seems like a reasonable description of the majority of superhero comics. The fact that scantily clad, preposterously proportioned women frequent these comics as well, again, like the image above, merely emphasizes the fact that these magazines for men are devoted to erotic looking — occasionally at women’s bodies, but more often at male ones.

The point here isn’t that comics are homoerotic, necessarily. Sharon Marcus has argued that, in many cases, women looking erotically at women functions as a part of heterosexual female identity, not lesbianism. The same could be said of superhero comics for men. Men gazing intently at men is a standard part of male heterosexual identity for many comics readers — and, for that matter, moviegoers.

Bodies, Time, and Space

Fashion photography pretty much includes at least one body in every image.

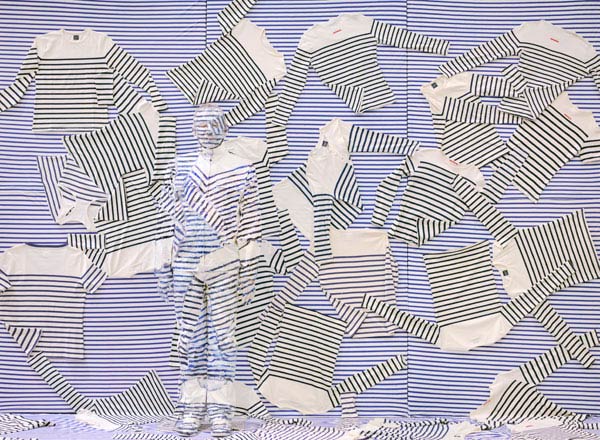

To look at fashion editorials as comics is to realize that this is not something which separates the two. On the contrary, most comics are almost as obsessed with bodies as fashion is. You may get a few panels of setting the scene or camera-panning over landscapes, but in most comics, in most panels, you see a human being (or an in-some-way humanized dog or cat or funny animal.)

Generally, I think, this is seen as logistical; to show somebody doing something in comics, you have to show their body over and over. Repetition creates narrative and time.

Fashion editorials, though, make you wonder. They have no narrative, and there is no real sense of time passing. Yet they still often use the same body and the same face — the same person — repeated in image after image.

You could say that, again, it’s just logistics — one model modeling is easier to schedule/cheaper to pay than 12, or however many, models modeling. No doubt there’s something to that. But it’s also true, I think, that the familiarity and the variation is a delight in itself.

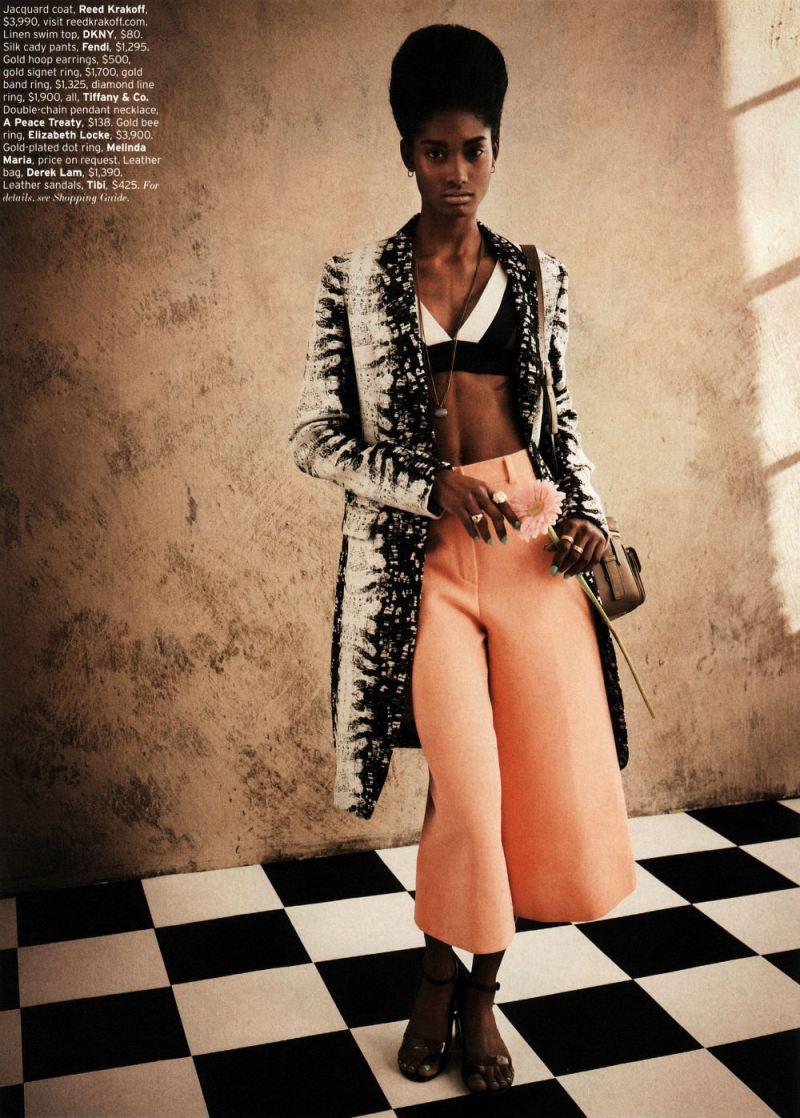

In the preceding three pictures near the end of the editorial, we see a full length, dynamic pose; a full length more demure pose — and then a dramatic close-up.

Much of the punch here comes from the bright color of the blouse and those dramatic expressive (Ditko?) hands, one eloquently touching her head, the other in the extreme foreground looking impossibly long and elegant— partially because of the nails, partially because the sleeve is pulled back from the wrist, and partially because the model just has amazing hands. But the image is also striking because it’s this woman, seen, up till now, mostly at a distance, and now, suddenly, brought forward.

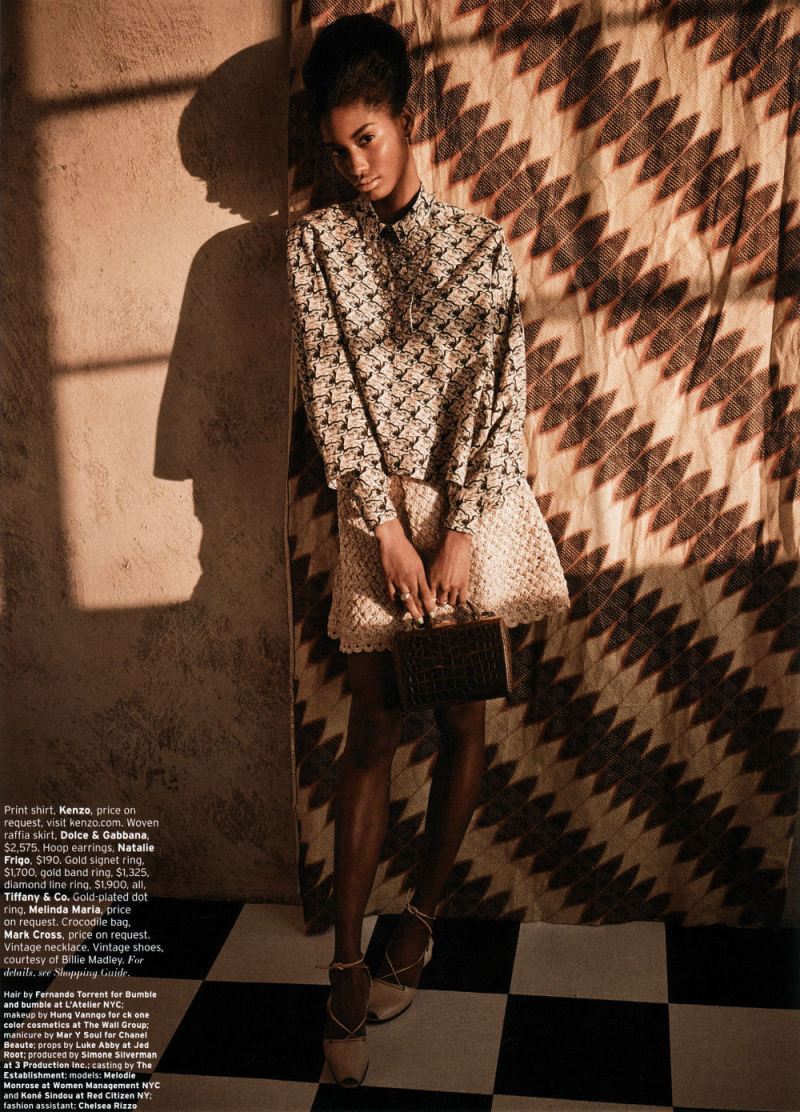

Similarly, the last image

Relies for its effect to some extent on the contrast with what came before. Instead of bold colors and bright light, we have earth tones and shadows; instead of looking right at us challengingly, her pose is demure, her gaze indirect. It seems to me like a deliberate anti-climax; a quiet grace note — which, again, gets much of its allure from the sense, not just of intimacy, but of increased intimacy compared to what has gone before.

You could argue that contrary to what I said earlier, this suggests a narrative, or the passage of time. Indeed, I think it points to the extent to which any identity is implicated, or filled up with, time; part of what we recognize in a self, or in a body, is that it’s the same self, or the same body. As Lacan says, there’s a delight in that recognition, and energy in (what Lacan sees as the illusion) of making the self coherent.

But if the repetition of bodies inevitably makes fashion editorials into pleasurable narratives, you could also perhaps say that narratives inevitably make comics into pleasurable repetitions of bodies. Or, in other words, from the perspective of fashion, the repeated selves in comics are not a logistical byproduct, but a pleasure and a goal in themselves.

_____________

I think there are other topics to talk about here: the link between commodified images and retro-nostalgia, for example, or the differing place of race and tokenism in comics and fashion. But since I’ve now posted the last image from the editorial, this seems like a good place to end things. I am curious — has anyone ever seen any discussion of fashion editorials as comics, or in relation to comics? I figure I can’t be the first, but a quick google search doesn’t really turn up anything. If anyone has links or references, let me know.