A version of this appeared in The Chicago Reader way back when.

_____________________________

Jennifer’s Body is a basic rape-revenge narrative. Towards the beginning of the film, stuck-up high-school hottie Jennifer (Megan Fox) is brutalized. Subsequently, she wreaks hideous vengeance on men in general, and, eventually, on the perpetrators in particular. Action, reaction, gallons of blood. It’s not clever, but it has a crude, inevitable elegance. It works.

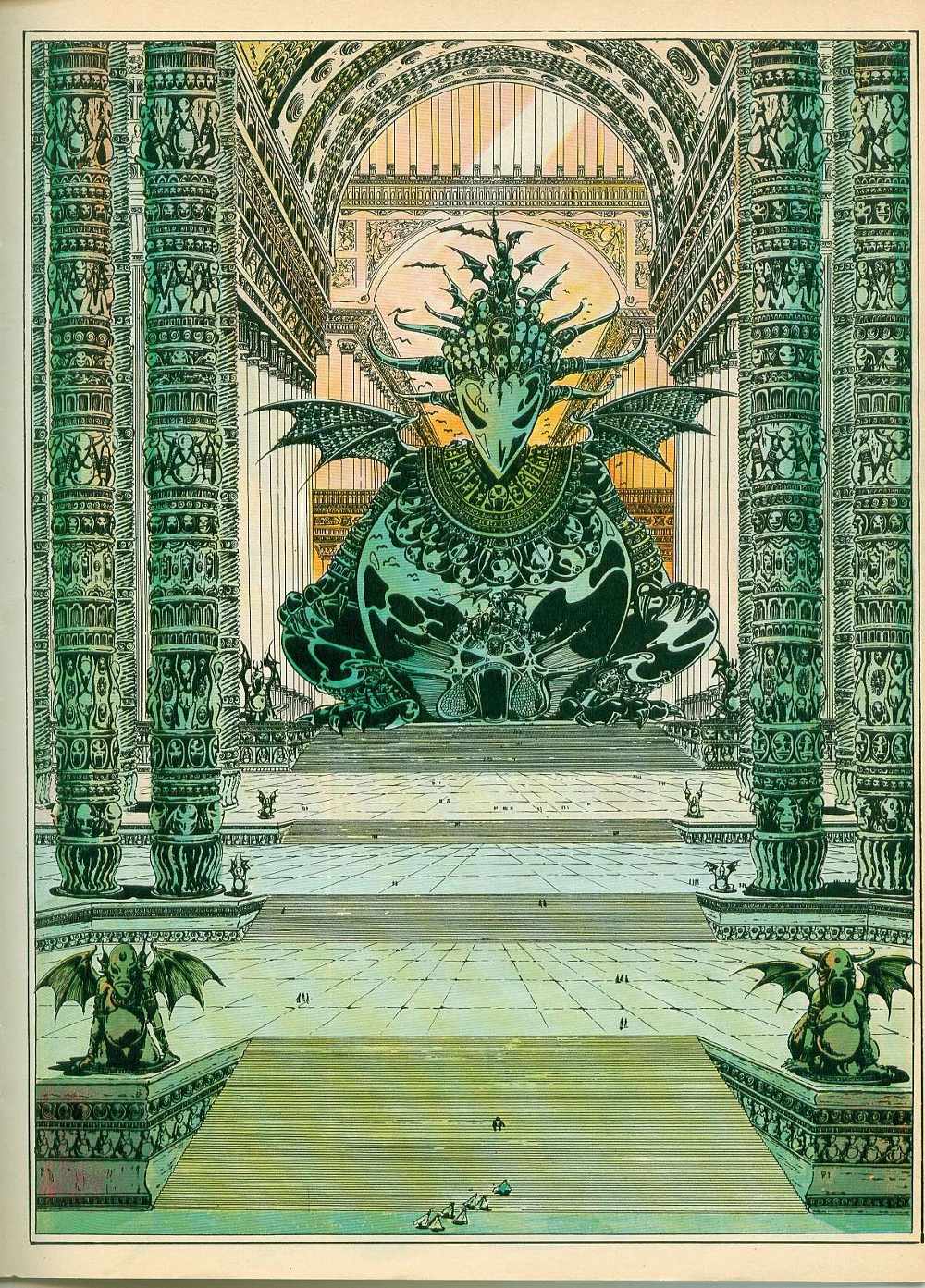

Or at least, it works in classic examples of the genre like I Spit on Your Grave or Ms. 45. Jennifer’s Body, though, isn’t satisfied with the formula. Writer Diablo Cody (Juno) and director Karyn Kusama want something a little smarter, a little more hip. They add some sparkling dialogue: in what is sure to become a classic line, Jennifer is described as “actually evil, not high school evil.” They include some wicked satire too; most notably Adam Brody’s gleefully oleaginous performance as an indie-rocker who earnestly explains how tough it is for bands these days just before butchering Jennifer as an offering to Satan.

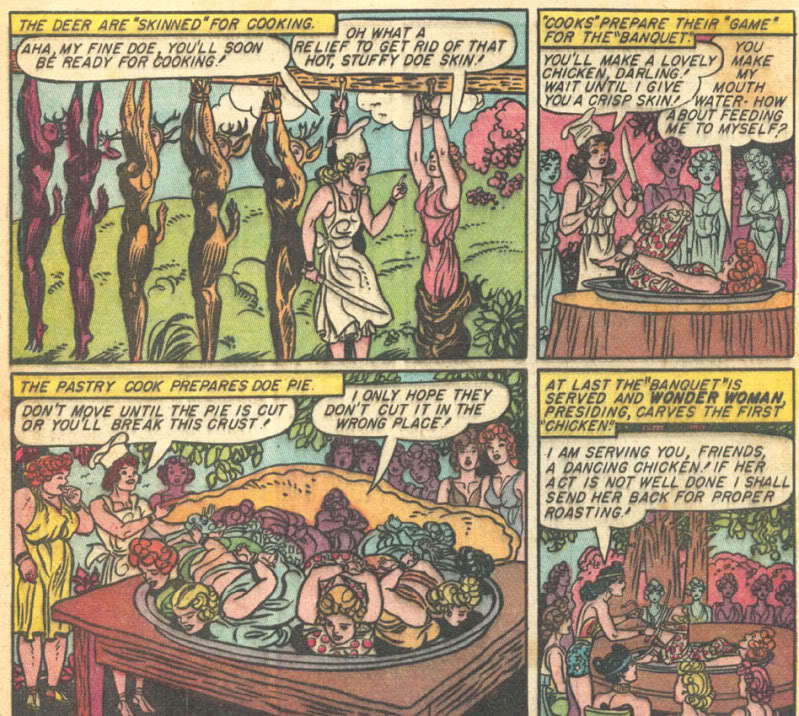

So far so good. But the filmmakers also tinker in more fundamental and, unfortunately, less successful ways. The visceral rush of the rape-revenge narrative is distanced, complicated, and ultimately squandered. They take the rape itself, and they make it not quite a rape, but rather a virgin sacrifice gone horribly awry. They make Jennifer not just a woman wronged, but a possessed demon, who kills not for retribution, but for food. They take the revenge, and they push it back all the way into the credits, presented in a series of still frames, and performed by the wrong person. And then they add a series of twists and turns, quasi-homages lifted from a melange of horror/exploitation gone by. Demon Jennifer turns evil like the guy in Christine and vomits like Linda Blair in the Exorcist. She stalks the prom like Carrie, and gets a point-of-view shaky camera shot courtesy of a thousand slasher films. The movie even takes a bizarrely unmotivated detour into women-in-prison films, of all things.

The most ambitious change, however, is the introduction of female bonding. The classic rape-revenge films drew their energy, in large part, from a celebration of, and anxiety about, the castrating power of second-wave feminism. Women, these movies averred, had been wronged, and those women were going to rise up and cut your dick off (literally, in the case of I Spit on Your Grave.) Movies like Ms. 45 even made a sustained critique of patriarchy, linking workplace harassment, rape, and the general marginalization of women into a single crime — punishable by death.

But while rape-revenge films make much of feminism, they don’t, generally, make anything of sisterhood. In both I Spit… and Ms. 45, the women are notably isolated. They tell nobody about their suffering or their plans for revenge, because they have no one to tell. The point of the films, indeed, is the spectacle of an isolated, lone, helpless, weak individual turning the tables on the patriarchy. In short, for all their feminist gestures, the movies are for men; they’re about how men interact with women, rather than about how women interact with each other.

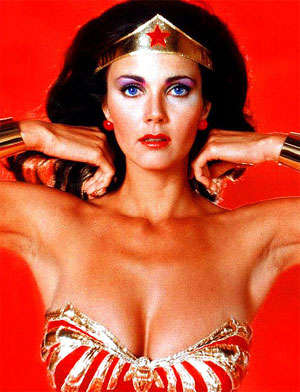

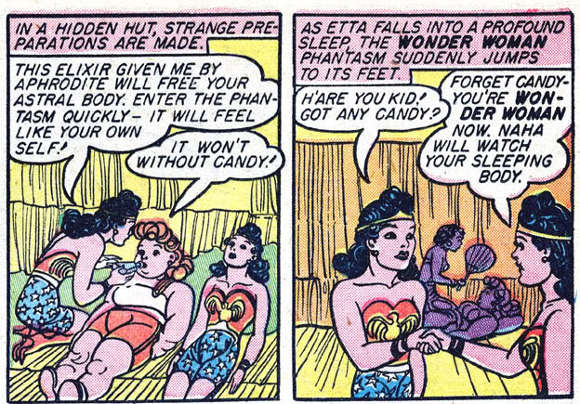

Jennifer’s Body is different. The central relationship of the film is not between Jennifer and her male oppressors/victims, but rather between Jennifer and her BFF, Anita, or “Needy” (Amanda Seyfried). Jennifer and Needy have been friends since nursery school, and they’ve remained friends even though Jennifer has blossomed into Megan Fox, one of the two or three sexiest women in the world, while Needy is merely run-of-the-mill jaw-droppingly gorgeous; i.e., a geek by Hollywood standards. In classic popular kid/geek stereotype, Jennifer is the dominant shallow demanding one, dragging Needy away from her boyfriend and out to bars, shooting down guys, and running around after indie rockers who are best left alone. Needy is the sensitive, smart, cautious one, always careful not to upstage her friend, and…well, you know the drill. Over the course of the movie, Needy realizes that she and Jennifer have grown apart, and that the best friend she once loved is now a shallow, jealous bitch, not to meniton a demon from the pits of hell who wants to eat Chip (Johnny Simmons), Needy’s sweet, long-suffering boyfriend.

The combination of rape-revenge with fraught female friendship isn’t, in itself, a terrible idea. Under the direction of more talented or thoughtful filmmakers, you could see it working out as the kind of feminist metaphor that Cody and Kusama seem, rather desperately, to be groping for. Jennifer’s victimization by, and subsequent embrace of, sexualized, partriarchal violence (“my dick is bigger than his” she says of one soon-to-be victim) could work as the wedge that drives her and Needy apart. Rape and the revenge it spawns could be set against or contrasted with sisterhood.

The problem is that, for this to work, the film would have to, at some point, sympathize with Jennifer. You’d have to understand why Needy loved her in the first place; you’d have to see the two of them interacting in a way which made sense of their friendship. This never happens. Jennifer is a bitch before she’s violated, and she’s a bitch after she’s violated. Her transformation into a succubus is a fulfillment of her character, not a negation of it — it seems, in short, to be what she deserves, both for her shallowness and for her sexual precociousness. When the two protagonists have their showdown at the film’s end, Needy tells Jennifer that she was never a good friend…and that seems to more or less be the case. Partially this may be Megan Fox’s acting limitations, but there’s never a moment where she does anything for Needy, or even seems to have straightforward affection for her. What did Needy ever see in her?

The movie does suggest an answer; one that is not at all, as it were, straightforward. The first time we see Jennifer and Needy, they’re sharing a meaningful glance and a flirtatious wave that causes a student sitting nearby to suggest aloud that they’re gay. The relationship’s temperature only rises after Jennifer is demonified; there are several suggestive scenes, and one smoking hot encounter on Needy’s bed with tongue and all. When Needy pulls away in disgust, Jennifer slyly mentions that the two used to “play boyfriend/girlfriend” at slumber parties.

That scene has been much publicized. But for all the brou-ha-ha, the film never seems to consider the possibility of Jennifer and Needy as an actual couple. Rather, the lesbianism is played for titillation, for shock value, and for laughs. Needy’s love for Jennifer is shown as a dangerous fascination that must be discarded. Cliff, the boyfriend is the sympathetic one; he’s obviously where Needy should end up, and part of Jennifer’s evilness is that she makes that impossible. When Jennifer does, in a way, possess Needy at the film’s end, it’s seen more as debasement than empowerment; a loss of self and of possibilities. In the typical rape-revenge, patriarchy is the evil to be overcome. Here, as the first line of the movie states, “hell is a teenaged girl” — or, more precisely, the friendships between teenaged girls. Cody claims that that’s somehow feminist, but I must confess, I don’t see it.