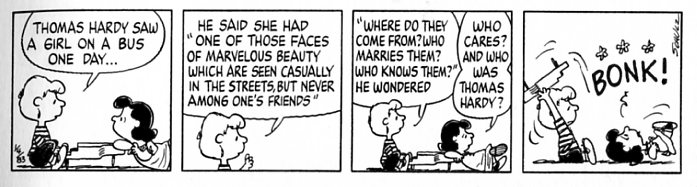

As regular readers know, over the last month and a half or so the blog has been engaged in a sporadic roundtable on the place of the literary in comics. I was recently reading the 1983-84 volume of Fantagraphics Peanuts collection, and came across a strip that seemed like it had interesting things to contribute to the discussion. Here it is:

So what does this have to say about the literary in comics? Well, several things, I’d argue.

First, and perhaps most straightforwardly, the strip can be seen as an enthusiastic endorsement of literariness. Schroeder — the strip’s most ardent proponent of high art — quotes Thomas Hardy. The second panel is given over almost entirely to Hardy’s words, which take up so much weight and space that they almost overwhelm Schroeder’s earnestly declaiming face. Lucy — Schulz’s go-to philistine — expresses indifference and self-righteous ignorance — for which she is duly and gratifyingly punished by Schroeder, who pulls the piano (marker of the high art she’s rejected) out from under her. Bonk!

In terms of the debate we’ve been having on this blog, you could easily see this as a pointed refutation of Eddie Campbell’s rejection of literary standards and literary comparisons. Campbell’s argument that literariness is not relevant to comics seems to fit nicely with Lucy’s “Who cares?” — while Ng SuatTong’s ill-tempered riposte seems quite similar to Schroeder’s.

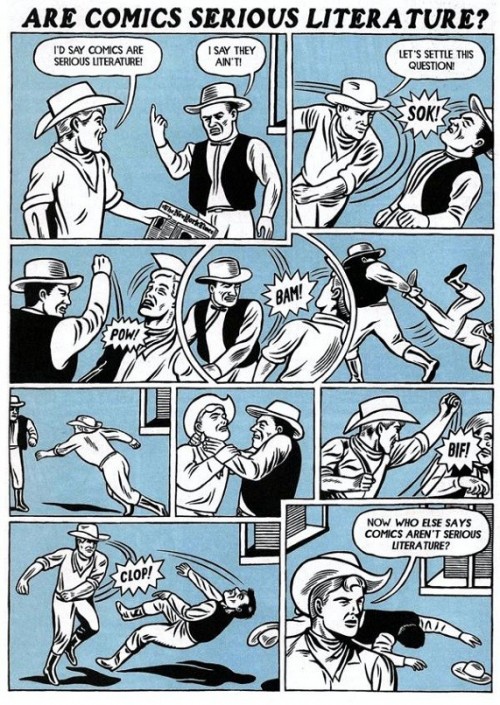

On second thought, though, Schulz’s attitude towards literariness can be seen as a little more ambiguous. It’s true that Schroeder, the advocate for high art, gets the last word. But the last word he gets is not precisely high art. On the contrary, it’s slapstick. The point of the strip, you could argue, isn’t the Hardy quote, which ends up essentially being little more than an elaborate set-up — it’s literariness there not for its high-art meaningfulness, but simply to signal “high art meaningfulness.” The real pleasure, or energy, of the strip, is in that last image, where Schroeder pulls out the piano — almost throwing it over his head and off panel, as if to toss aside the very possibility of including high art in a comic strip. From this perspective, the strip might be seen as being in the vein of Michael Kupperman’s “Are Comics Serious Literature?” (HT: Matthias.)

The point isn’t so much to advocate for literature as it is to use comics to giggle at the idea of advocating for literature in comics — a position that Eddie Campbell would probably find congenial.

One last, perhaps less schematic,possibility is to think about the strip in terms of gender. It’s interesting in this context that, while Schroeder is generally the advocate for high art, he’s also generally uninterested in, or immune to, the appeal of romance — he’s one of the few characters in the strip who (as far as I’ve seen) never has an unrequited crush. Lucy, of course, has a crush on him, and it’s usually she who brings up images of marriage or love or domestic bliss, only to have Schroeder disgustedly reject them.

This strip is different, though. Hardy’s words are not just a default marker of high art; they’re in particular a paen to a woman’s (or a particular kind of woman’s) “marvelous beauty,” and a speculation — with more than a little longing — on who such beautiful people marry. It sounds more like something Charlie Brown would say about the little red-headed girl than like something Schroeder would say to Lucy.

Lucy’s lack of interest, then, can be seen as not (or not merely) philistine, but as tragic — Schroeder is finally, finally talking to her about love, and she can’t process it or understand it.

You could attribute this to her soullessness, I suppose — she is blind and doesn’t deserve love. But you could attribute it to Schroeder’s soullessness. Certainly there’s a cruelty in babbling about the beauty of random unobtainable women to someone who you know is head-over-heels in love with you. For that matter, the Hardy quote itself seems to exhibit some of his most maudlin and least appealing tendencies; it’s pretty easy to read it as a self-pitying lament for the fact that beautiful women are human beings, rather than simple objects to be collected by men who admire them in the street. The high-artist idealizes Woman and ignores the woman sitting in front of him. Lucy’s utter indifference could then read as a recognition that Hardy is indifferent to her — and Schroeder’s violence as a tragi-comic extension of Hardy’s violence. In this case, the literary is neither defended nor ridiculed, but is instead a kind of doppelganger — a shadow of meaning cast by the comic, the meaning of which is in turn cast by it.

Literature, then, appears for Schulz in this strip as an ideal, a butt, and a fraught double. As I’ve said on numerous occasions, I don’t really have any problem comparing comics and other forms (Charles Schulz is a greater artist than Thomas Hardy, damn it.) But I do feel like the anxiety around those comparisons, in every direction, sometimes ends up drowning out potentially more interesting conversations about how, and where, intentionally and despite themselves, comics and literature can meet.

Bill Watterson thinks the Lucy/ Schroeder relationship was based on Schultz’s relationship with his first wife:

“Reading these strips in light of the information Mr. Michaelis unearths, I was struck less by the fact that Schulz drew on his troubled first marriage for material than by the sympathy that he shows for his tormentor and by his ability to poke fun at himself.

Lucy, for all her domineering and insensitivity, is ultimately a tragic, vulnerable figure in her pursuit of Schroeder. Schroeder’s commitment to Beethoven makes her love irrelevant to his life. Schroeder is oblivious not only to her attentions but also to the fact that his musical genius is performed on a child’s toy (not unlike a serious artist drawing a comic strip). ”

http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB119214690326956694.html

I don’t know what to make of your gender reading. I mean, are you trying to say men can be “high-artist” and women are not, or Schultz might think so? Lucy can’t understand “High Art” because she’s gendered female?

And what does that have to do with the real life events that might influence the strip?

High art is often gendered male…not infrequently because, like this Hardy quote, it aggressively objectifies women. My point isn’t that Lucy can’t understand high art because she’s a woman, but that the high art on offer here deliberately treats women as things — and that that might well alienate women.

I think it fits pretty well with your point, actually. Schulz is gendering high art, and linking women’s (at least potential) alienation to that gendering. You could see it, as you say, as a thoughtful and sympathetic take on his wife’s and his trouble — especially since, again, Schulz does occasionally indulge in this kind of Hardyesque romanticization/objectification of women too (most obviously with the little Red Haired Girl, who isn’t a person, but just a trope in Charlie Brown’s neurosis, much as this girl on the bus is for Hardy.)

Really enjoyed this post.

And it’s either the speculation about mysterious beautiful Women or the fancy language that alienates Lucy, because she’s paying attention in the first panel.

So she is!

Maybe both?

——————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

In terms of the debate we’ve been having on this blog, you could easily see this as a pointed refutation of Eddie Campbell’s rejection of literary standards and literary comparisons.

——————-

That’s along the line of some Fox News “pundit” charging that liberals who don’t consider homosexuality a vile perversion are thereby rejecting all moral standards.

If one razzes criticizing a literary composition via the methods used in judging cuisine, that is not a “rejection of cooking criticism standards”; it’s pointing out that they’re absurdly inappropriate in this instance.

For less of a “stretch,” this old anecdote: A friend of critic John Simon, upon leaving a performance of “Macbeth,” would loudly announce, “It’s good, but it’s not ‘Oklahoma!'” Then, exiting a performance of the famed musical, would call out, “It’s good, but it’s not ‘Macbeth’!”

So, if someone gripes that ” ‘Oklahoma!’ is good, but it’s not ‘Macbeth’!” is an idiotic remark, is that a”rejection of literary standards and literary comparisons”?

Or rather wondering, does it make sense to criticize a gloomy drama by the exact same standards one would a rousing musical? To expect, say, “Where the Wild Things Are” — about as perfect a work as one could ask for — to have the character complexity, sweeping portrait of a society, the range of humanity, of a “War and Peace”?

——————-

Campbell’s argument that literariness is not relevant to comics seems to fit nicely with Lucy’s “Who cares?”…

———————

(Sarcasm Alert) Yeah, Campbell is a proudly doltish ignoramus, who never heard of all those high-falutin’ literary types.

———————-

The real pleasure, or energy, of the strip, is in that last image, where Schroeder pulls out the piano — almost throwing it over his head and off panel, as if to toss aside the very possibility of including high art in a comic strip.

———————–

That’s a mind-bogglngly warped reading. Schroeder’s reacting to Lucy, in effect “removing his pearls before swine.” It’s hardly a case of Schulz — who regularly featured “high art” mentions in “Peanuts” (Snoopy owned a Van Gogh; “From his first appearance at the piano on September 24, 1951 Schroeder has played classical pieces of virtuoso level, as depicted by Schulz’s transcription of sheet music onto the panel. The first piece Schroeder played was Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in G Minor,” as http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schroeder_%28Peanuts%29 notes) — “toss[ing] aside the very possibility of including high art in a comic strip.”

Indeed, there’s a fascinating section in that Wikipedia entry:

————————–

Schroeder is usually depicted sitting at his toy piano, able to pound out multi-octave selections of music, despite the fact that such a piano has a very small realistic range (for instance, and as a running joke, the black keys are merely painted on to the white keys). Charlie Brown tried to get him to play a real piano and young Schroeder burst into tears, intimidated by its size. This was attempted again where Violet convinces him to do the same thing, but he just couldn’t do it.

————————-

Does not that Schroeder can “classical pieces of virtuoso level” on a minimally-equipped toy piano tie in with Schulz’s being able to deal with psychologically complex themes, achieve emotionally moving effects, in a simplistically-drawn daily-gag comic strip?

(And one can imagine Schulz, upon suggestions that he take up painting, or write a novel, being likewise intimidated…)

——————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

The point isn’t so much to advocate for literature as it is to use comics to giggle at the idea of advocating for literature in comics — a position that Eddie Campbell would probably find congenial.

————————–

(Sarcasm Alert) Yes, Eddie Campbell, who’s written some of the richest, deepest, most complex and psychologically nuanced comics ever, who’s best captured the facets of Life, is actually advocating comics being simplistic adventures and joke-fests. Suuure…

—————————–

It’s interesting in this context that, while Schroeder is generally the advocate for high art, he’s also generally uninterested in, or immune to, the appeal of romance — he’s one of the few characters in the strip who (as far as I’ve seen) never has an unrequited crush. Lucy, of course, has a crush on him, and it’s usually she who brings up images of marriage or love or domestic bliss, only to have Schroeder disgustedly reject them.

This strip is different, though. Hardy’s words are not just a default marker of high art; they’re in particular a paen to a woman’s (or a particular kind of woman’s) “marvelous beauty,” and a speculation — with more than a little longing — on who such beautiful people marry…

——————————-

Rather than “Schroeder’s soullessness,” doesn’t that “he’s also generally uninterested in, or immune to, the appeal of romance” tie in with this fascination with idealized women? Why, he’s like some computer-game nerd so enraptured with Lara Croft that he’s oblivious to any interest from flesh-and-blood women.

But then, in the history of “Peanuts,” has any girl except Lucy expressed romantic interest in Schroeder? There might be a hint at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schroeder_%28Peanuts%29 , but the skim I only have time for failed to reveal it. From that site, more re the Lucy/Schroeder relationship:

——————————–

Schroeder’s other distinguishing mark as a character is his constant refusal of Lucy’s love. Lucy is infatuated with Schroeder, and frequently lounges against his piano while he is playing, professing her love for him. However, Beethoven was a lifelong bachelor, and Schroeder feels he must emulate every aspect of his idol’s life, even if it is insinuated that he reciprocates Lucy’s feelings. In a story arc where she and the rest of her family have moved out of town (also seen in the TV special Is This Goodbye, Charlie Brown?), Schroeder becomes frustrated with his music and mutters disbelievingly that he misses her, realizing that, despite his animosity towards her, Lucy has unwittingly become Schroeder’s muse and he cannot play without her (he parodies Henry Higgins by saying, “Don’t tell me I’ve grown accustomed to THAT face!”). Sometimes, he gets so annoyed with Lucy that he outright yanks the piano out from underneath her to get her away from him which became a running gag; on one occasion both Lucy and Frieda lounge on Schroeder’s piano, until he yanks it from beneath them both after Frieda mistakenly thinks Beethoven is a drink rather than a composer…

——————————–

(Emphasis added)

——————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…the Hardy quote itself seems to exhibit some of his most maudlin and least appealing tendencies; it’s pretty easy to read it as a self-pitying lament for the fact that beautiful women are human beings, rather than simple objects to be collected by men who admire them in the street.

——————————–

That melancholy bit of romantic longing translates to regretting “the fact that beautiful women are human beings, rather than simple objects to be collected by men who admire them in the street”?

A similar moment from Adrian Tomine: http://imgc.artprintimages.com/images/art-print/adrian-tomine-the-new-yorker-cover-november-8-2004_i-G-61-6122-JKUF100Z.jpg

(And can’t women likewise wonder about some handsome stranger they see in the distance?)

It’s said that for those whose only tool is a hammer, their tendency is to go around smashing things. If you’re a feminist, from what we hear here, all you see are those evil males hating and oppressing women everywhere.

—————————-

The high-artist idealizes Woman and ignores the woman sitting in front of him. Lucy’s utter indifference could then read as a recognition that Hardy is indifferent to her — and Schroeder’s violence as a tragi-comic extension of Hardy’s violence.

—————————–

“Hardy’s violence“..??? Hardy’s anecdote is seen as not only regretting “that beautiful women are human beings, rather than simple objects to be collected,” but as VIOLENCE.

Yeah, it sure is an incomprehensible phenomenon that modern women can be pro-women’s rights, yet reject identifying as “feminists”…

Mike, it seems pretty odd to me to treat Peanuts, which was never fully collected during publication, as some sort of unified work, as if you can being in some other strip from some other decade of the authors life to refute an interpretation of a single strip. I mean, maybe it’s even perfectly consistent and Schroeder no longer loves Lucy in the 80s but did in the 60s when she was his “muse”?

At any rate Watterson interpretation has more poetic ring to it than yours so I’m sticking with that for the time being.

Eddie Campbell really does often seem to strongly suggest that we shouldn’t judge old comics by literature because old comics aren’t very good, and the medium itself isn’t very good. I’d agree that it’s difficult to reconcile that with his own work, which is very attuned to literary nuance, and very ambitious. But…people are complicated and confusing and sometimes contradictory, you know?

Well clearly both Schulz and Campbell are being self-aware about their pulpiness, on some level. And perhaps Schroeder (and Jack the Ripper) are just gay, and that settles that.

(I haven’t looked at any Eddie Campbell work besides From Hell, which I realize Frank Miller wrote.)

Alan Moore wrote it!

Oh yeah right. It’s arcane, not crypto-fascist.

——————–

Pallasp says:

Mike, it seems pretty odd to me to treat Peanuts, which was never fully collected during publication, as some sort of unified work, as if you can being in some other strip from some other decade of the authors life to refute an interpretation of a single strip. I mean, maybe it’s even perfectly consistent and Schroeder no longer loves Lucy in the 80s but did in the 60s when she was his “muse”?

———————–

By a “unified work,” you apparently mean that all the characters act with absolute consistency and predictability. As even the focused entry at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schroeder_%28Peanuts%29 shows, though there are no 180-degree “reinventions,” certainly characters show different facets at different times, as different situations develop. Is this not routine in “unified works” such as novels, where persons go through a “character arc”?

I would hardly call her his “muse,” actually inspiring creativity. Indeed, she’s routinely actively anti-creativity: “Lucy has often spoken of getting Schroeder to give up his piano, such as getting him to realize that married life has financial hardships and he may have to sell his piano in order to buy her a good set of saucepans. On two occasions, Lucy went so far as to destroy Schroeder’s piano in an attempt to be rid of the ‘competition’ for his affection, but both attempts failed…”

I see her more like some familiar aspect of the creative environment, without which “the art doesn’t flow.” Like some writers need to have music playing in the background.

As for using other “Peanuts” strips to “refute an interpretation of a single strip,” is not the original interpretation heavily dependent on details of relationships, situations in the the “Peanutsverse” set up in other strips?

And I’d hardly call Schroeder’s feelings for Lucy as “love,” more like “fond toleration.” But, can’t one be massively irritated even with with those whom one deeply loves? Infuriated with their “blind spots” or maddening habits? (“You’re eating with your mouth open again…”)

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Eddie Campbell really does often seem to strongly suggest that we shouldn’t judge old comics by literature because old comics aren’t very good, and the medium itself isn’t very good.

————————–

Oh? Where do you get that “strongly suggests” bit? And where is his sweeping, wholesale dismissal of “old comics” — which includes bunches of masterworks — as “not very good”? Where does he say that the comics art form itself is “not very good”?

—————————

Bert Stabler says:

…And perhaps Schroeder (and Jack the Ripper) are just gay, and that settles that.

—————————

Schroeder, perhaps. But Jack the Ripper? Only a hetero would feel so strongly about women…

Pingback: The Princess and the Pony by Kate Beaton review – strength is a farting horse | ComicsClub.in