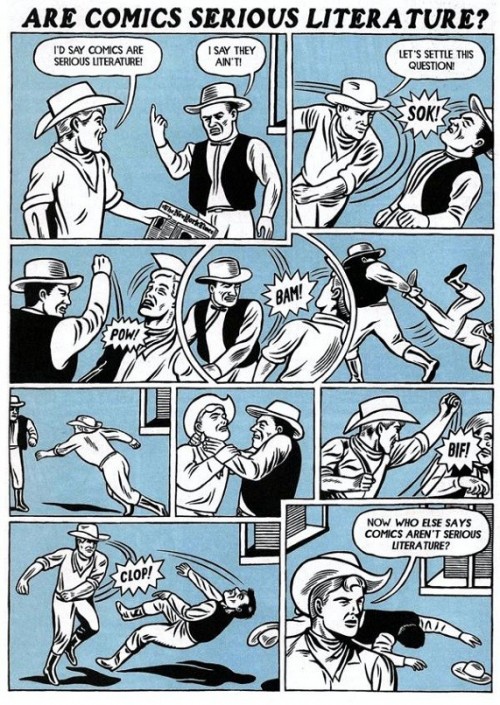

Michael DeForge wants you to know that comics aren’t just for kids anymore.

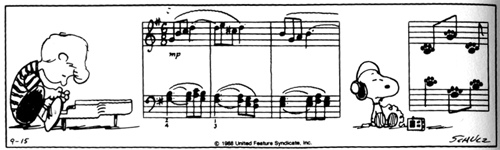

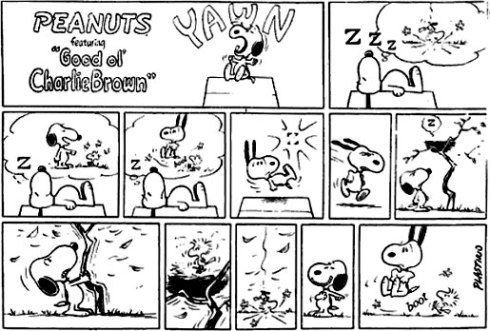

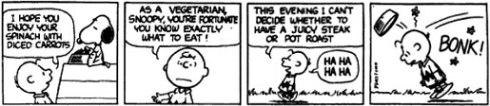

The cover of DeForge’s Incinerator is a bland desecration of comics past. Snoopy’s instantly recognizable backside suffers a decontextualizing detournment, transformed into a torso for the wrong bald-headed kid walking through a typically scrungy alt comics landscape, his tail a bulbous, inexpressive phallus between legs lifted with jaunty incongruity above the junk and debris. Bleak plant-like and rock-like globs ooze at stochastic intervals, the stripped-down iconic style suggesting the world of Peanuts determinedly uglified by underground grunge.

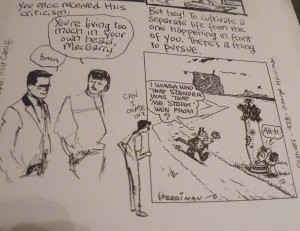

The adultification, not to say adulteration, of Peanuts is a familiar alt-comics trope. Chris Ware and Dan Clowes tend to try to capture Schulz’s rhythms and then layer on sex, drugs, scat, and other supposed markers of maturity. DeForge, refreshingly, goes for a more blatant approach.

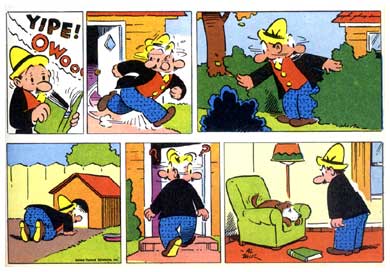

The sad, anatomically challenged amalgamation is set upon by a gang of college students; weaponized maturity mugs the beloved icon of childhood,leaving it groaning in a ditch. The torso has to be taken to a vet while the rest of the sorry creature goes to a hospital. Separated, the beagle body dies, leaving only that bald-headed kid, suffused with pathos.

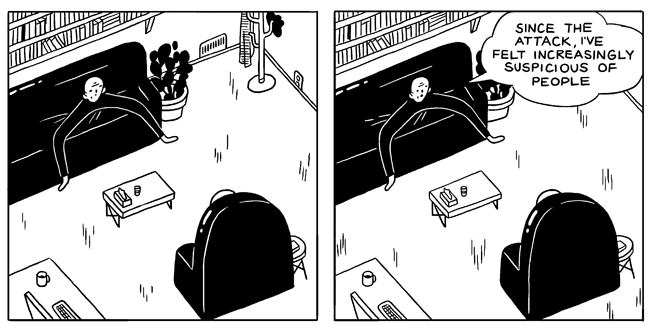

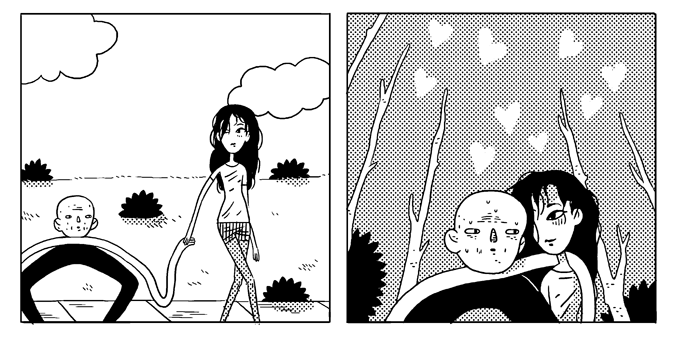

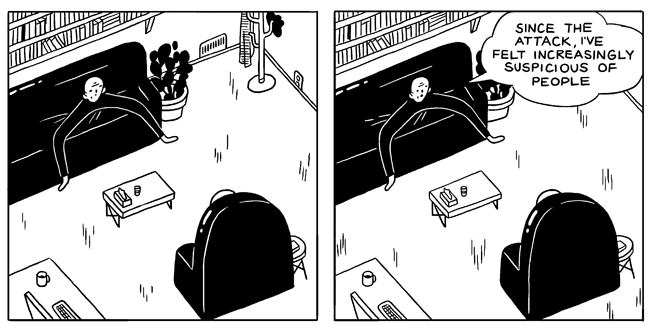

Rather than the Schulz’s grass-level camera, we’re here treated to a crazy look down; a god’s eye view if god were stuck up there with the knick-knacks on the teetering top of a bookshelf. Or, perhaps, we’re looking down at the comics page itself; the sophisticated adults with the book of childhood spread out before us, distant and oddly angled, too small to fall into. We stroke our chin with the analyst in the chair, seeing the mundane neuroses in the formerly fanciful images.

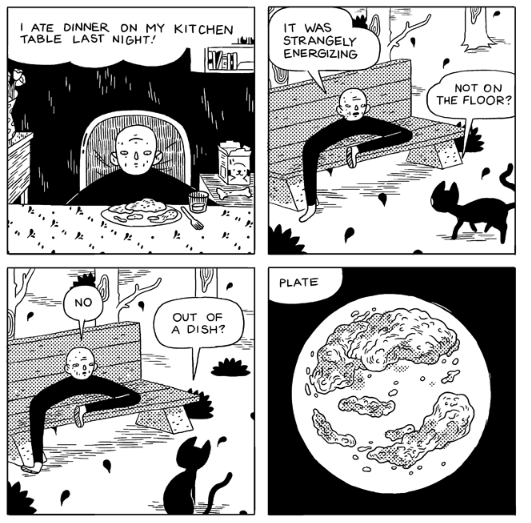

The de-beagled hero goes through his alt comics paces, attending group therapy, reveling in nostalgia for the comic icons of his childhood,

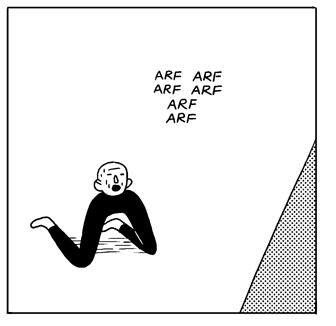

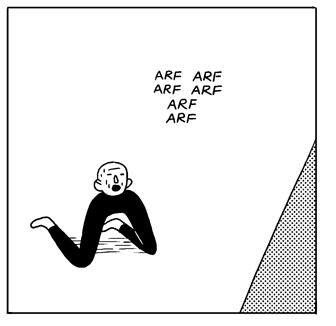

participating in a tender romance. On the final page, the beagle torso, like all those childhood pamphlets, is chucked in an incinerator. The image before it burns is of the girlfriend in dominatrix garb whipping the naked protagonist as he barks. The innocent goofiness of childhood is chucked for sexual perversion. Get rid of that doofy tale and you can see the penis which was hidden there all along.

It’s certainly possible to see this as an absurdist Fort Thunder satire of the alt-comics and underground obsession with Peanuts, with being grown up, and with the conflation of the two — artsy hipster tripped out weirdos mocking the differently literal immature maturities of Chris Ware and R. Crumb. But it’s also possible to see Incinerator as a kind of avuncular celebration of those immature maturities; a humorous, self-aware, nostalgia for other folks’ nostalgia, and for the role it’s played in the development of comics past.

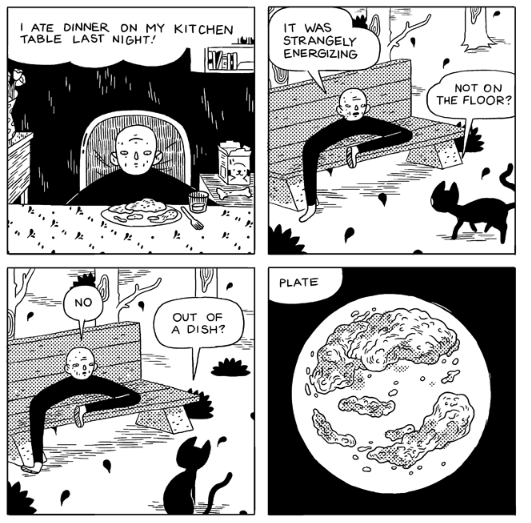

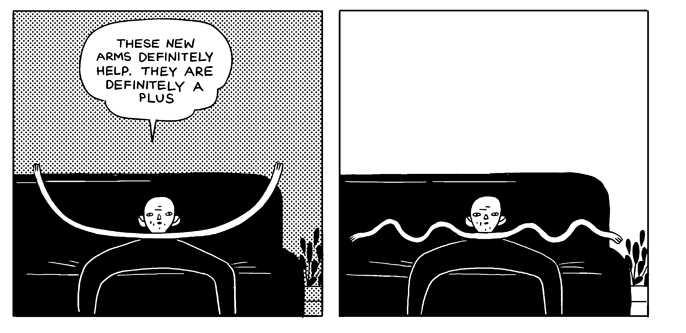

Growing up, trying new things, is energizing. The Rorschach-blot-feces lunch forms an interesting pattern, it’s very repulsiveness an ironic attraction. Adulthood is still what’s on offer, but an adulthood less bleakly blank than Ware’s or Clowe’s, in no small part because it sees Ware and Clowes as comfortingly familiar predecessors. Thus, adulthood here means building on Schulz’s absurdity (and Clowes’ and Ware’s) rather than on his (or their) existential despair. It means using Peanuts, and Peanuts’ successors, as visual tropes rather than as a blueprint. Adulthood becomes an at least intermittently pleasing agglomeration; lack of integration, the loss of the coherent circumscribed world of childhood, becomes its own pleasure. The lost thing provokes not just nostalgia, but joy at the missing piece. If Lacan’s child looks in the mirror and feels celebratory at the illusory image of an integrated self, DeForge’s adult looks at the comic and feels celebratory at the illusory image of a haphazard collage cyborg, the aging self as bits and pieces of one’s own past.

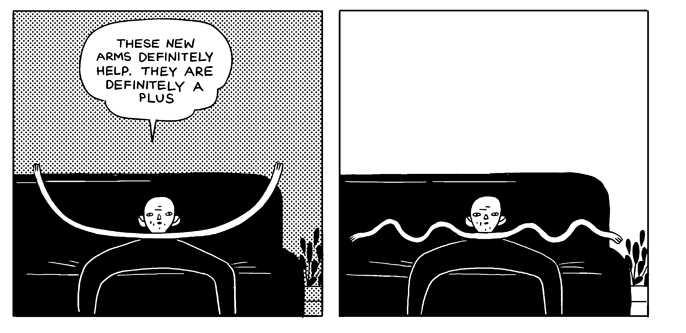

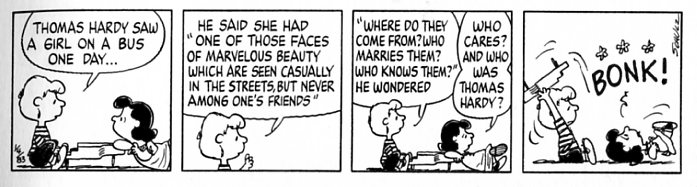

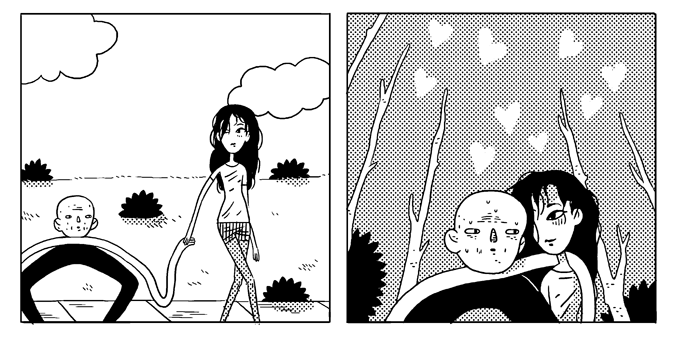

Part of that delightful adult collage, it seems, is the image of a woman. One of the female college students in the crowd at the beginning of the story later becomes our protagonist’s rom/com, Jeff Brown sweetie, and finally his dominating mistress.

That flaccid arm across her shoulder contrasts with the cruel, stark phallic trees framing the hearts which seem less like a vibrant expression of love than like de rigeur filligree tacked up to the moire background. This is not a story, but the garbled image of a story; not love but the parodic potency of recognizing parodic lack of potency. The girlfriend, as marauder or sweetie or dominatrix, never speaks. Unlike Schulz’s Lucy, or Sally, or Marcy, or Peppermint Patty, she has no tale of her own. The protagonist’s self is the past, but the woman’s self is simply image, signalling various comfortably denuded narratives of coherence: teen rebellion, love, sex. The silent, faceless Snoopy is discarded, the silent, many-faced female is picked up with new arms. The one coherent attribute of adulthood is a recognition of absurdity. All the rest, no matter how soaked in sentiment — be it comics, woman, torso, or heart — is just a part of the caducous bricolage.