Inspired by Frank Bramlett’s satisfyingly rich 1/23/14 PencilPanelPage post, “How do Comics Artists use Speech Balloons?” (which is the first in Frank’s promised and promising series on the representation of talk in comics), I, too, have decided to embark on a two- or three-part exploration of a discrete comics element utilizing a theoretical framework with some application to particular comics. My focus is time, and I will use this first part to sketch some of the concepts I will be drawing from, and invite readers to share their insights into how time works in comics that have caught their eye. Five weeks from now, part two will explore a few select panels and pages that—in my opinion—do interesting things with the representation of time.

Never yet having engaged in sustained exploration of the representation of time, it has nevertheless often been a component of what I explore when I think about comics. Sometimes it is simply the nifty nature of dual time possible in a panel; consider, for example, a graphic memoir like Fun Home, in which the speech balloons emerge from the drawn child while a narrative voiceover in the captions presents an adult “take” on the scene below. There is also the type of narrative time that gets built as a comics reader moves around a comic, returning to panels on previous pages, picking up threads that were dropped and resumed, or making connections between and amongst instances of action, events, characters (Scott McCloud does justice to this movement in Understanding Comics, of course, as he also brings the gutter into this consideration, reminding us that we continue playing out the scene via imagination each time we hit a gutter, and thus extend narrative time in interesting and highly subjective ways).

Thierry Groensteen’s exploration, in his System of Comics, of reader actions with non-contiguous panels and the work s/he does to connect disparate moments spread through a full-length comic, adds an additional dimension to this expansion of time (yes, and space, which is hard to decouple from time). Via what he terms a system of “arthrology” (the anatomical reference here is to joints and jointedness), the reader collects information from across the comic, interweaving (he uses the term “braiding”) elements large and small to make meaning, and though he does not discuss this primarily in terms of time, can we not see it as a novel challenge to the linear nature of narrative time? If we generally think of readers pulled from first page to last in a linear progression from start of text to end of text, it is both refreshing and liberating to think of the comics reader becoming adroit at stopping and starting time at will, hitting the pause button in a sense, and then rewinding and fast forwarding in a very individual search for meaning and alternate forms of continuity. This can be quite literal: think of the moments you held your finger on a page in anything by Chris Ware, and returned back to an earlier page to tease out a connection…then toggled between them to establish an artificially created, but viable, contiguity between panels that are (no longer) separated by page distance?

In “Duration in Comics,” an engaging article published in the Winter, 2012 (Volume 5, Number 2) issue of European Comic Art, Sebastien Conard and Tom Lambeens bring several concepts of narrative time to comics, attempting to find language to talk about the layering of multiple types of time in both single panels and works as a whole. Conard and Lambeens plumb philosophical concepts of time, such as Henri Bergson’s notion of duration, which refers not to clock time, but rather “…time as felt or experienced, not time as thought or measured.” (96) They consider other forms of subjective time, including Gilles Deleuze’s exploration of how memory alters time (and time memory) (97)—you can apply this both to a character or narrator’s memory as its shapes the showing and telling of events, experiences, etc. as well as to the reader’s memories and their impact on such things as “reading” time, i.e. how long it takes to make one’s way through a given work. Ultimately, Conard and Lambeens are interested in the multiplicity of time in comics—that there are often many different kinds of time operating both objectively (in the panels, pages and words of a comic), and subjectively (in the mind of a reader).

Can you offer a particularly deft representation or enactment of time in a comic, or do you have some thoughts – general or specific—on the topic of time in sequential narrative? I’ll be continuing this thread in part two, and will provide some provocative examples, but I’m eager to hear from others on the subject while I gather this evidence for you.

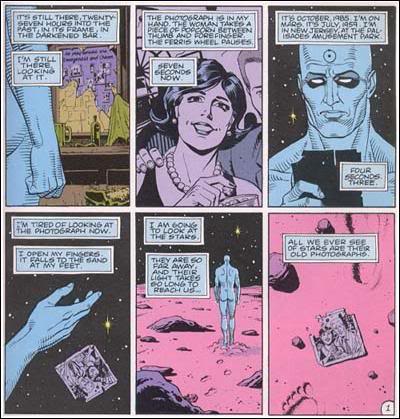

from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen

I’ve got a piece from a bit back talking about how space turns into time and vice versa in comics, looking in particular at Escher and Watchmen. It’s here.

I linked to this in Frank’s piece, but a few years ago I wrote “This is Not a Sound”: The Treachery of Sound in Comic Books in which I discuss the role of word balloons in giving the illusion of action across panels in a scene. Since word balloons simulate sound and sound is only coherent in terms of its relation to time – our experience of sound helps to provide closure between static images depicting change.

This is a great question, Adrielle. I’ve been thinking about these ideas in relation to how comics depict memory, an issue Groensteen begins to address in Comics and Narration (trans. Ann Miller), the sequel to The System of Comics. His points on comics or visual narratives that devote each page to a single image bring up some interesting questions on time, memory, and the role of the reader.

In this passage he’s discussing wordless novels such as Masereel’s Passionate Journey & Ward’s Gods’ Man as well as more abstract word & images narratives such as Martin Vaughn-James’ The Cage:

“In works of this type, there are never more than two images visible to the reader at any one time, split across two pages—one on the left-hand and on one the right-hand page (although sometimes only the latter is used). The space within which iconic solidarity comes into play is less that of the page—a flat surface immediately accessible at a glance—than that of the book, a foliated space that must be discovered progressively. The dialogue among the images depends on the persistence of the memory of pages already turned.” (Groensteen 35)

Aside from the section of Watchmen you included at the end of this post, I think, for me, The Cage is one of the most fascinating depictions of time in a visual narrative, since it emphasizes the subjective nature of movement through time itself and does away with a linear progression of one moment to the next. In that sense, it’s the closest I’ve seen in a comic (so far) to the cut-ups of William Burroughs or novels like Anna Kavan’s Ice.

An oft commented upon aspect of the comics reading experience is that upon opening to a page we see all the panels at once, and then read the page panel-to-panel. The upshot for a theory of comics time is that reader can shift between synchrony and diachrony, and maybe even duration and event time (though I’m not sure the film analogy really works).

Here’s a piece I posted here on the topic a couple of years ago.

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2010/12/through-space-through-time-four-dimensional-perspective-and-the-comics-by-eric-berlatsky/

Since everyone else is linking to their essays on time in comics: here’s mine on time and movement in Bergson, La Jetee, Muybridge and comics (using examples from EC and Fantastic Four). I argue that perception plays a huge role (gestalt-like principles, for example) in reading comic book time. It’s not all social construction.

I write a bit about seriality and continuity in comics in relation to time and the coherence of identity narratives in my dissertation – though that is a different way of thinking about time – i.e. in relation to the story of who we are – and the ruptures that take place in the linearity of time that are sutured over through elision and assertion.

Noah, Osvaldo, Eric and Charles: Thank you very much for linking to your previous writings on the subject of time in comics. I am looking forward to carefully reading each, and am always struck by the variety of entry-points into the subject of time and narrative (Noah’s space becoming time, Osvaldo’s sound continuity as a representation of time passing, Eric’s emphasis on simultaneity of experience—the comics reader apprehending multiple moments in time concurrently, and Charles’ philosophical meditation on static and moving time [which, from a brief skim, looks like it goes in some nifty directions re: time travel, perception and circularity].

Brian—yes, I haven’t read Groensteen’s sequel, but it does seem to continue the discussion of iconic solidarity in System of Comics (i.e. non-linear grouping of information, images, etc. from across the book, backwards, forwards and every other which way)…. I like that the focus here –in the Groensteen quote you provide, and in your own commentary–is on the critical role of reader memory in this process. What I love about that is the way time kind of flips on itself when, for example, you need to know the full text—have read all the way to the end at least once, but really several times (as Charles Hatfield often argues)—in order to get all the parts working together properly (so that you can “remember” what happens at the end of the comic, say, while you carefully examine an early panel). I agree that this isn’t limited to image texts; I remember being very struck by this with Modernist “experimental” works like Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood and Eliot’s Waste Land.

Nate—I’m glad you brought synchrony and diachrony into the conversation; it seems really apt for a discussion of time in comics. Also, is “event time” limited only to film? It seems readily present in most discussions of narrative time, I think. Hence, another interesting connection.

Osvaldo—Your second comment—on identity continuity—calls me back to a question I often ask of the visual representation of faces and bodies in graphic memoirs. Since the graphic memoirist must draw the self over and over again, across time, s/he makes choices about what to change and what to maintain, and often we don’t have the static “same” representation of self that we have with typical iconic characters like Snoopy, say, but rather, an affect-laden set of shifts –body shape/size, facial features, expressions, etc., some of which are suffused with meaning that never gets expressed directly in the words (abjection, for example). Can you say more about “the ruptures that take place in the linearity of time that are sutured over through elision and assertion?” That’s one hell of a sentence!

Hi, Adrielle.

I’m working on an article manuscript that explores how time is constrained by dialogue, so I’m very glad that you’re exploring it here on PencilPanelPage!

You asked for some examples, and two come to mind immediately. One general example is Howard Cruse’s *Stuck Rubber Baby* because it is a graphic novel that works very similarly to graphic memoir. (Cruse says it is not an autobiographical work but that a lot of it is drawn from his own personal life experiences.) The narrator is present in the text, so we see him in current time telling what happened in the past, etc.

The second example is a very specific moment from Jessica Abel’s *La Perdida* (pp. 59-61 in my copy of it). The main character is Carla, and she is in the middle of personal identity crisis. Abel draws this gorgeous series of images where Carla’s sense of reality is suddenly assaulted, and her sense of self is merged with a story from earlier in the text about William Burroughs. I think Abel deftly blends time and identity here. I’d love to hear what you think about it.

btw: Thanks for the nice words about my last post!

The first issue of Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg! introduces a “GoGang” countdown timer that he returns to a few times throughout the series as seen in pages 6 (http://i.imgur.com/cWYryB3.jpg) and 27 (http://i.imgur.com/uIqTpeL.jpg) of issue #1.

What GoGang means and why the timer is significant isn’t revealed until later in the issue; it adds a degree of both anticipation and suspense to the reading experience: What’s going to happen when the timer hits zero? Are the characters impatient for it to get there or do they dread it and want time to stretch out as long as possible?

It also assigns a discrete duration to each page down to the second. On page 6, a single-panel splash, lasts 20 seconds. On page 27, four panels represent 3:51 in narrative time.

Arielle: I will try, but sometimes my sentences take on lives of their own. ;)

I have not really worked with graphic memoir and have only read a few, so I can’t comment in relation to that, but actually I argue that even iconic characters (like Batman) change so much that it is impressive that they remain recognizable as the same character. This is of course obvious if you look at a character over a long period of time, but even between issues and/between artists the depiction of characters can change in drastic ways and yet remain recognizably itself. I think part of that recognizability has to do with how readers elide certain changes and assert others (in both conscious and unconscious ways) as to make a narrative of the character that makes sense for the current incarnation that they enjoy (this narrative can work both within the confines of actual narrative continuity or be a meta-narrative that includes aspects of the character’s story as a comic character, and frequently a combination of both).

The ruptures I mention take a variety of forms. The most common is just the advancing yet cyclical way time works in serialized superhero comics (so that Spider-Man can be both a college student faced with the issues of student protest of the late 1960s and a dude in his late twenties considering returning to finish his degree 30+ years later) that require elision in order to line up properly. However, at the same time elided storylines are frequently re-asserted at a later date by a different writer. This disjunctive points in time are kind of amazing to me as they not only make narrative of a character’s identity over time incoherent, but the ruptures themselves are productive sites that writers and artists use to create more stories, further muddying notions of linear time.

Adrielle,

Awesome post. I have also been thinking a lot about time in comics. Osvaldo’s mention of Batman (and how we somehow construct a single coherent character from a multitude of distinct and not altogether consistent depictions) brings to mind all complications inherent in the way time works in mainstream superhero comics.

Of course, we all know that comic book characters don’t age – except when they do. Some characters age, others have backstories explaining their failure to age, and some just seem ageless. More confusingly, as Osvaldo notes, typically the adventures of a particular superhero are meant to have occurred within a time frame of (usually) no more than ten years, even though their stories, taken literally, stretch over 50 or 60 or 70 years of publications (in short, Batman has always been Batman for about a decade – hence his origin story always occurs something like 20ish years before the time you are reading it, regardless of when that is).

Confusing stuff. I think a lot of critics are too quick to write off this sort of thing in superhero comics as (i) motivated purely by commercial concerns, and (ii) obviously silly and incoherent. But as Osvaldo notes, this sort of play with time is also both creatively productive and narratively fascinating. I think it is worth thinking about all of this a good deal more, and I am looking forward to your next few posts!

I was unclear about the event/narrative time thing… I meant to write something more to the effect of “event as space” (Deleuze) vs. “event as time” in film.

Speaking of what characters look like over time, I put together this progression of Peter Parker some years ago: Who is Peter Parker?

Several years ago I wrote an essay about Alan Moore’s representations and manipulations of time. It survives in the eternal now of the internet:

http://www.philobiblon.com/isitabook/comics/index.html