N.B. This post is a modified and revised version of a paper delivered at the 2014 meeting of ICAF (the International Comic Arts Forum) in Columbus, Ohio.

________

What interests me most about the urge to define and classify (What is and is not Comics? What is and is not Fine Art?) is never the end-points reached (determined criteria, essential characteristics, asserted and defended definitions) but, instead, how the process entails an ever-shifting set of priorities, and reveals, as much through its negations and dismissals as through its affirmations and acceptances, that the very act of classifying items—placing them here and not there—shapes the critical reception and the way that we see and read a work. Classify the 20th Century Swiss-German artist, Paul Klee, as a modern painter who experiments with color and line, and you will regard the 1938 painting, Insula Dulcamara, shown above, as a prime example of such experimentation. This will probably entail situating Klee’s paintings in certain early 20th Century movements, and engaging in comparisons to the work of other like-minded painters such as Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, and August Macke. But if you change context and ask whether his work shares any affinity with comics, you might find that new analytic approaches and comparisons become possible, and even valuable.

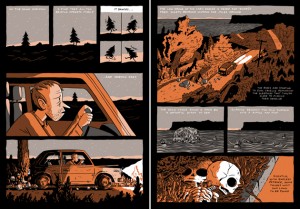

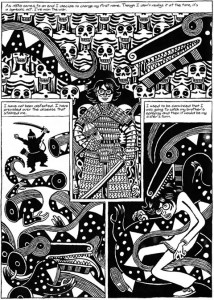

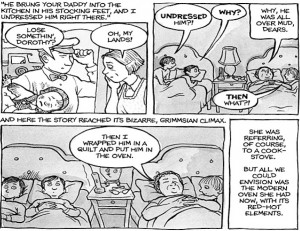

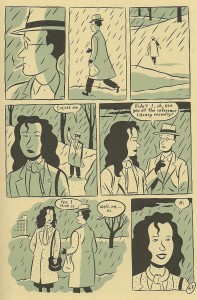

For me, an essential characteristic of comicsness is a certain kind of spareness; regardless of the degree of embellishment of figures and background, a good comic—through its non-realistic, two-dimensional representations—seems to offer “just enough” for me to regard, without delineating an object or a figure so particularly that its uniqueness overshadows its representative function.

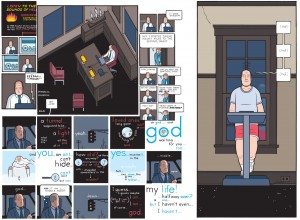

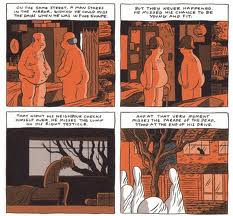

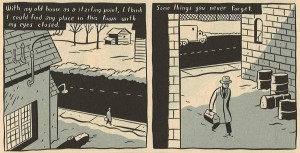

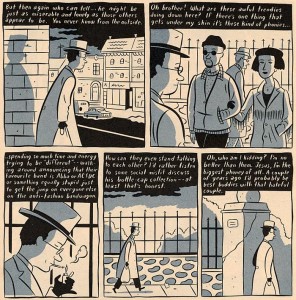

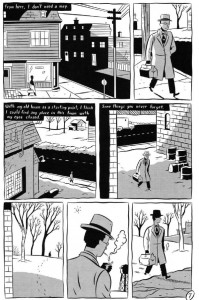

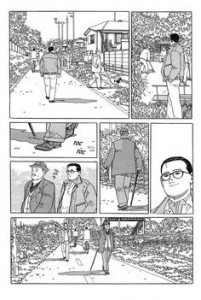

Jordan Wellington Lint, in Chris Ware’s Acme Novelty Library #20,

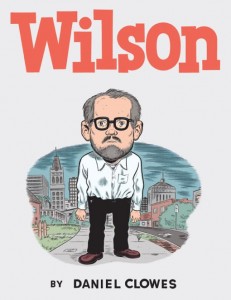

David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp,

and Daniel Clowes’ Wilson are distinct, but they can also easily be read as a type: the middle-aged man at odds with environment, self-satisfied and self-loathing, simultaneously in search of, and in ironic detachment from, pleasure. Sometimes, reducing a characterization down to its core elements—a few lines, the evocation of a body position and its carriage, a repeated facial expression—can convey a state of being to a reader/viewer more effectively than might a realistic depiction.

For Klee, paring down to these essences was a critical aspect of his work, particularly his studies of nature. He writes:

“[Graphic art] gives the schematic fairy-tale quality of the imaginary and expresses it with great precision. The purer the graphic work, that is, the more emphasis it puts on the basic formal elements, the less well-suited it will be to the realistic representation of visible things.” (The Thinking Eye: The Notebooks of Paul Klee 76).

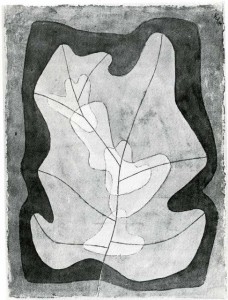

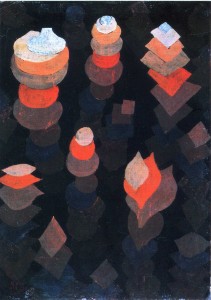

Freed from the demands of realism, Klee can consider how things work and of what they are composed (“The object,” he writes, “grows beyond its appearance through our knowledge that the thing is more than its outward aspect suggests” [63]), as he does here with a single leaf and a group of flowers.

Klee’s flowers have been called primitive and childlike (and, by the way, Klee would have taken no umbrage at these designations; he often argued for the merits of so-called primitive art, children’s art, and the work of the mentally ill and believed they should be exhibited more often), and these two examples should give you some sense of Klee’s commitment to the distilled object. I am reminded of “amplification through simplification”—a key trait of comics for Scott McCloud, but I am also reminded of these lines from Wallace Stevens’ “The Idea of Order at Key West:”

She was the single artificer of the world

In which she sang.

And when she sang, the sea,

Whatever self it had, became the self

That was her song, for she was the maker.

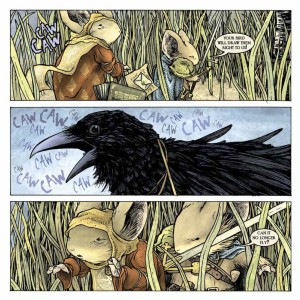

“[Klee’s] flowers,” writes Richard Verdi in his essay, “Botanical Imagery in the Art of Klee,” “remain creatures of the imagination, calling to mind no known species and according instead with Klee’s preference for archetypal forms in nature – for images of organic life that are typical rather than individual and may thus evoke the patterns and principles that underlay much of natural creation.” (Paul Klee: Dialogue with Nature. Ernst-Gerhard Guse, ed. Prestel-Verlag, 1990: 25-26). Key to these principles is Klee’s understanding that dynamic movement and growth can be conveyed in still images, echoing the fact that our limited perception blocks us from seeing just how much may be happening under a seemingly still surface. “Pictorial art,” he writes, “springs from movement, is itself fixed movement, and is perceived through movements.” (“Creative Credo”) In his 1918 “Creative Credo,” Klee considers two examples from life: an apple tree in blossom and a sleeping person.

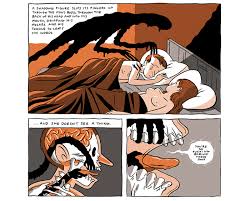

Though we see only stasis, each has multiple types of movement contained within: inside the tree, roots are drawing water and nutrients from the soil, xylem and phloem are circulating nutrients throughout the organism, reproduction is taking place in the flowers, trunk and bark and leaves are growing, photosynthesis is occurring… all at different rates and in different ways. Little of this is visible on the surface. Similarly, the sleeping person’s heart is pumping, blood is circulating, the digestive system is active, the lungs are expanding and contracting, the kidney is processing materials, and the mind is dreaming, but we see only a person who is not moving.

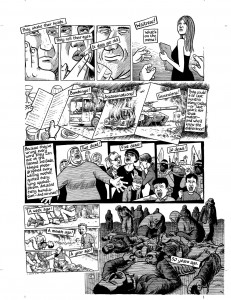

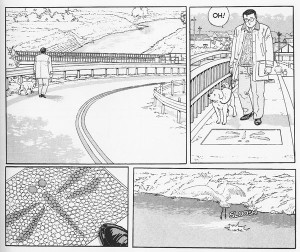

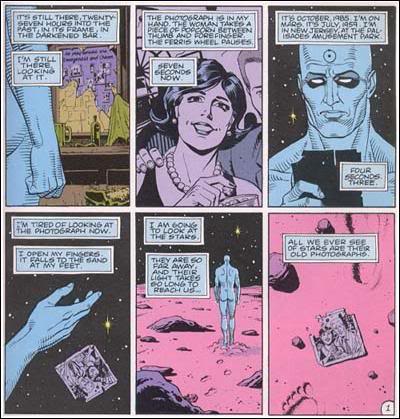

Comics recognize and exploit this notion of contained movement, hidden processes, and internal states. Obviously, the very nature of sequential art suggests this: carried from panel to panel, the reader experiences a dynamic narrative with spatiotemporal verisimilitude (time passing, action occurring, locations changing) despite the fact that the panels and pages are composed of still images. But there is more to this, as Sebastien Conard and Tom Lambeens argue in their 2012 article, “Duration in Comics” (European Comic Art 5:2 Winter 2012: 92-113). Taking Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth as their focal text, Conard and Lambeens explore the rhythm established by a particular page layout. Arguing that the rhythm of a work teaches “slow-down” to the reader, they write: “It is within the page space that musical repetition and alteration unfolds. As a result, there is the rhythm of the frames: small rectangles repeated and alternating with bigger ones. . . . In short, this page is a game of repetition and alteration of verbal, iconic, and spatiotopical elements. And so, the mechanics of the ‘slow down’ are clear.” (102)

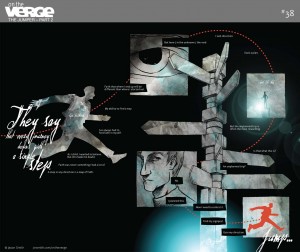

Intriguingly, they posit that single panels—not just pages, or multiple non-contiguous panels linked by iconic solidarity, as Thierry Groensteen would offer– can do this too: “…[E]ven the frame can bulge with many micro-narratives. This means not only that a panel can contain many moments tangled up together, but also that it necessarily has a possible duration that each reader can unfold personally.” (105) It has always seemed clear to me that the panel is not the minimal grammatical unit of a comic, as many contain intra-panel elements that can be looked at independently of the panel, and certainly of the page. An eyebrow in Toufic El Rassi’s Arab in America, a brick in Herriman’s Krazy Kat, a shadow in David B.’s Epileptic or Aleksandar Zograf’s Regards to Serbia: each can be untethered from its panel for independent examination. But Conard and Lambeens are adding another dimension to this intra-panel scrutiny, and it accords with Klee’s sense that dynamism can be present in the still, or as Sarah Wyman puts it in “The Poem in the Painting: Roman Jakobson and the Pictorial Language of Paul Klee,”(Word and Image 20:2 2004: 138-154): “the crystallization of moments in motion.” (139) By suggesting that time—duration—is no more an inherent and fixed aspect of a panel as it is of a comic as a whole, Conard and Lambeens capture the special relationship between work and viewer, the unique and particular stretch of time that is simultaneously evinced by a particular image, and accorded by a viewer to that particular image.

For Klee, this same sense of duration maintains. Wyman continues: “Klee identifies time in his own paintings as implicit in the making and viewing of the works, as well as potential in the forms themselves.” (142)

So, when we look anew at Klee’s images of the natural world, we begin to see that it is not a single moment in time that is captured, but a complex interplay between the pictured elements and the viewer’s perception of both time and movement, just as takes places between comic and viewer.

Returning to Insula Dulcamara once more, we can ask a fresh set of questions of the painting. Might we have, as Conard and Lambeens notice in Jimmy Corrigan, “many moments tangled up together?” Perhaps we do; many art historians and critics have offered plausible connections between details within this painting such as the “steamer” in the upper-right corner, the autobiographical P (for Paul?) with a face in the center, the curve of lines that appear coast-like with key moments and aspects of Klee’s life, including an important trip to Tunisia in 1914, his intense study of Homeric tales during the last years of his life, and his excruciating condition of scleroderma. As recently as July, 2014, a persuasive theory for reading the seemingly pictorial elements of lines and dots as Arabic and Latinate letters cleverly distorted and resolving into the words “Paul Klee”—the artist’s signature– was put forth by Chris Pike in his article, “Signing Off: Paul Klee’s Insula Dulcamara” (Word and Image 30:2 2014: 117-130). Pike’s argument is particularly comics-affiliative in that it privileges verbal and visual interplay and notes a movement from letter to letter counter-clockwise through the pictorial space beginning at the central P. This movement must be initiated, traced, by a viewer who sustains his/her gaze for a period of time, just as a reader makes his/ her way around the panels and pages of Chris Ware’s work.

If comics theory can shed light on Klee’s work—and I’ve gestured at only a few of the many ways it does– it stands to reason that it may be profitably applied to other works of “fine art.” This could lead to an expanded notion of comics, yes, but it also might lead to something even more beneficial. If we practice looking at fine art – single works of art–through the lens of comics, we might return to individual comics panels and intra-panel elements with augmented attentiveness and some valuable resistance to the inexorable pull of narrative that drags us too quickly ever onward to the next panel and the next and the next.