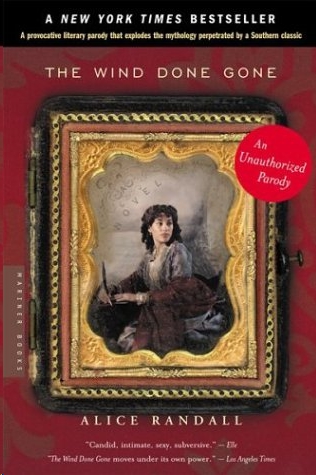

Alice Randall’s “The Wind Done Gone” is superior to the Margaret Mitchell novel it is based on in many respects. Though Mitchell’s prose is quite good, Randall’s is better , earthier and more poetic at once (“It’s a pissed bed on a cold night to read words on paper saying your name and a price.”) Randall’s economical, short book also avoids Mitchell’s tendency to ramble. But perhaps most surprising in a sequel/parody, Randall’s book makes more sense.

Alice Randall’s “The Wind Done Gone” is superior to the Margaret Mitchell novel it is based on in many respects. Though Mitchell’s prose is quite good, Randall’s is better , earthier and more poetic at once (“It’s a pissed bed on a cold night to read words on paper saying your name and a price.”) Randall’s economical, short book also avoids Mitchell’s tendency to ramble. But perhaps most surprising in a sequel/parody, Randall’s book makes more sense.

It’s a staple of fan fiction to fill in the blank spaces and plot holes. Still, Randall manages to do so with unusual grace. Much of Mitchell’s drawn out plot and her surprise twists are built on her characters lack of self-knowledge. Rhett is so afraid of giving power to Scarlett that he won’t tell her he loves her, even after they marry — and then, finally, he falls out of love with her, thump. Scarlett, for her part, thinks she loves Ashley and hates Mellie, until Mellie dies and she realizes, no that was all a mistake. Ashley has a similar storyline; he loves Scarlett until he realizes he doesn’t and never did. Mellie thinks Scarlett is her best friend even though Scarlett spends most of her life loathing her. Everyone seems utterly severed from their own emotional life. It strains credulity that one character could be this gob-smackingly dumb; but two? three? four? It starts to seem like carelessness.

In Randall’s book the source of the stupidity isn’t carelessness. It’s racism. The main characters in Gone With the Wind can’t know themselves, because if they knew themselves, they’d have to know about black people, and then their world would collapse. Mitchell’s characters, as seen by Randall, aren’t dumb; they live in a society of secrets and lies, in which not knowing is the basis of their existence. So Rhett doesn’t just fall out of love with Scarlett; rather, he always was in love with her half-sister, Mammy’s daughter Cynara, and his vacillations in love are the result of his painful uncertainty about marrying, or loving, a black woman. Ashley, for his part, never declares for Scarlett not because he’s a dishmop, but because he’s gay; Mellie has his black lover whipped to death at one point. And Scarlett, so set on not knowing herself, is not just stubborn, but has a real secret or two — a lifetime spent refusing to think about the fact that her beloved maid and surrogate mother slept with her father, and a lifetime spent refusing to think about her sister.

You’d think that looking unflinchingly at the racism in Gone With the Wind would make the white characters unsympathetic. In fact, though, Randall’s Scarlett, and Rhett,and Ashley are all significantly less awful than Mitchell’s. In Mitchell’s version, they’re all just horrible people, indecisive, whining, opaque to themselves, and fighting ceaselessly on behalf of slavery because they suck. Randall, in contrast, grants them the context that has deformed them. Rhett’s decision to become a Confederate soldier at the last minute, for example, is seen in GWTW as a triumph, and is therefore unforgivable. In Wind Done Gone, it’s portrayed as a painful lapse; a mark of how much racism touches even a man who, in many respects, has been able and willing to get beyond the prejudices of his society. (“R. fought and tried to die in a Confederate uniform to save this place,” Cynara thinks of her lover, and later husband. “I have tried to forget this, but I remember.”) Scarlett’s blank self-centeredness becomes more understandable when we see her parents’ marriage as loveless, and lack of self-knowledge seems more understandable when we learn her life was in no small part a lie. Her mother was partially black,and concealed her past and her own emotional investments from family, and especially from her daughter. GWTW famously (and counter-intuitively for a romance) concludes in bitterness and the break-up of a marriage; Randall’s is the book with the not exactly traditional, but still happy ending. The Wind Done Gone can manage forgiveness because it is able to talk about what needs to be forgiven; GWTW is filled with too much hate to arrive at love.

___________

Ruthanna Emrys’ novella “The Litany of Earth is version of “The Wind Done Gone” for evil fish-creatures. Where Randall presents GWTW from the perspective of the slaves and freed blacks, Emrys looks at H.P. Lovecraft’s mythos, particularly his Innsmouth stories, from the perspective of the monsters — and from the perspective of Lovecraft’s own vile racism. The main character, Aphra Marsh, has had much of her family hunted down and killed by the authorities, who also subjected them to brutal medical testing. Innsmouth people are still regularly policed by government spies; the parallels to the U.S. Japanese concentration camps, and to Hitler’s genocide, are drawn explicitly.

In discussions of Lovecraft, I’ve often seen fans argue that the horror in his stories is not linked directly to the racism. Instead, they say, the terror is tied to his atheism — to the apprehension of an infinite, indifferent cosmos, which was not built for humans and does not care about them.

Emrys keeps the cosmic emptiness in her story. Marsh’s people repeat a litany, in which they number the people of earth, from the distant past to the distant future, who have lived and will live and will all pass away. ““After the last race leaves, there will be fire and unremembering emptiness. Where the stories of Earth will survive, none have told us.” But the emptiness and meaninglessness don’t lead to horror. Instead, “In times of hardship or joy, when a child sickened or a fisherman drowned too young for metamorphosis, at the new year and every solstice, the Litany gave us comfort and humility.”

I think that’s right; knowing the universe is alien isn’t a horrible or fearful thing unless you first believe, as Lovecraft did, that the other and the alien are terrifying. The cosmic horror is horror not because the cosmos is intrinsically horrible, but because Lovecraft was racist. The indescribable gibbering darkness, the unnameable monstrosities; they’re indescribable and unnameable for the same reason that Scarlett and Rhett are irritatingly dense — because racism means you’re not allowed to know those other people, over there, which means you also can’t know yourself. Racism poisons Gone With the Wind, and it poisons Lovecraft’s world too. In Lovecraft and Mitchell that’s the shadow that can’t be named, and that neither wind nor war can blow away.

I wouldn’t reduce the abyssal dread in Lovecraft to his racism, but I agree that the racism is related, obvious and can’t be dismissed. He gets a lot of fear from it, in fact, so I’d call it integral, too. But I wouldn’t ignore his fear of poor whites, either, who are treated fairly similarly. I’d say what’s interesting about it all is the way the supposedly superior traditions of Western mastery over the world is persistently coming up empty, whereas the mocking of this mastery through the various non-rationalized, noumenal connections the non-whites and even the poor white trash have towards the radical Cthulhu otherness ultimately prove the latter correct about our foundational, ontological beliefs. That is, to me, how Lovecraft manages to express really profound anxieties with his racism (even if the reader doesn’t share the racism or class hatred).

Also: it makes sense that most of his lead characters would say many of the bigoted things they say, even if the author didn’t share those views.

I think Lovecraft’s class anxieties towards poor whites are racialized through his eugenic fears; it’s all about terror of degeneration and undermining racial purity (just like his misogyny and homophobia end up in a kind of indiscriminate racialized stew.)

I’d agree that there’s a desire in Lovecraft for the racial other, too; debasement is a terror, but also a desire for him, I’d say. That’s the case for Mitchell as well; several commenters (including Linda Williams) have pointed out that Scarlett is a blackface character in some ways, and gets her moral force from the way her struggle is linked to slavery (there are a number of explicit points in the novel which talk about her Irishness as a genetic strength/weakness.) Randall’s revelation in Wind Done Gone that Scarlett is, in fact, partially black, is brilliant in no small part because there are a lot of textual clues to that effect in Gone With the Wind.

fwiw, I actually like Lovecraft’s best work more than Emrys’ story, I think, though I do like the Emrys quite a bit.

And I think we actually agree on Lovecraft, for the most part, which is a nice change!

I read somewhere that Innsmouth was based on Lovecraft’s discovering that his grandma was Welsh. I think you’re right that he sees the white underclass as a degenerate version of whiteness, closer to non-whiteness. I’m not sure that he doesn’t see certain whites as being naturally inferior, though, regardless of the racial mixing. But both fears are related to a general fear of humanity (which he sees as whiteness) becoming more inhumane. I mean, I wouldn’t dismiss his hatred of poor whites as being somehow lessened because it supervenes on another hatred. That would assume that there’s somehow a rational basis for the other bigotry. All bigotry is rationalized on the basis of something else.

Yeah, I think we agree, but I probably laugh more reading Lovecraft, I bet.

I don’t know that you’d win that! I find him awfully funny.

I wonder about all you “cry racism” guys — is racist thought or writing as bad as racist behavior? Are you just worried racist thought and writing will lead to or reinforce racist behavior?

Wouldn’t you rather have a genuine racism appear in writing than the sort of disingenuous shoehorned rainbow utopia that passes for culture today? All I want in my art is a profound personal vision — give me Celine over Lena Dunham or who the fuck ever.

I wonder about you “cry anti-racism” guys. If all you want in your art is a profound personal vision, then you should just be reading Mein Kampf 24-7, right? That’s a personal vision. Go for it.

Of course, you don’t actually want to read Mein Kampf all the time, presumably, because it’s not very well written, and you don’t actually just want to read a profound personal vision that involves hating Jews, because that’s kind of nauseating and depressing (at least, I assume you wouldn’t.)

Since your point is pretty much completely incoherent, it’s difficult for me to know what you’re talking about, or what you think you’re talking about. As to what I’m trying to do in this post, I”m thinking about the way that racism affects works of art that matter to me. You claim your looking for “profound personal vision”. But what is that vision composed of? Is racism, which is hardly personal or idiosyncratic, part of that vision? How does racism affect the other parts of that vision (Mitchell’s romance plot, Lovecraft’s horror.)

I’m not utterly rejecting either Mitchell or Lovecraft as artists. I’m thinking about how their racism affects their art. And yet, somehow, that results in a defensive, somewhat bizarre attack on Lena Dunham (who isn’t universally lauded for her racial sensitivity, as far as I know.) I feel like you either didn’t actually read the piece, or else are so committed to anti-anti-racism that you composed the comment before you did.

Here’s an idea; why not enjoy my profound personal vision, hmm? Wouldn’t you rather have genuine anti-racism than the kind of disingenuous meaningless burble about profound personal visions in your comment?

I’d like to see a short answer to just one of Kris’ questions:

Is racist thought– and I’ll specify “racist thought in literature”– as bad as racist behavior in society?

(And if you want I guess you can include in the latter the relatively new category of “micro-aggressions.”)

I don’t think there’s exactly a short answer. Racist beliefs tend to power racist actions (though not always; racist policies can also be out of convenience or economic interest or what not.) Talking about art is talking about ideas and how they work. So, the point in this piece is not to condemn racist thought (I thought that was pretty clear; this isn’t a barn burning piece.) It’s to think about how racism works in these works, and think about what that means for how racist beliefs work, which seems to have some relevance to how racist beliefs work in general.

I mean, in this piece I argue that Lovecraft is worth reading because his vision of how racism works is really insightful and thoughtful and moving. He’s absolutely a racist, but he’s smart about how racism works. I don’t know how that fits into your paradigm of racist beliefs being evil or worse than racist actions.

I would say that the effort to say, we shouldn’t talk about racist beliefs because real racism is happening elsewhere, lets talk about that — that is what is known as bullshit. Anti-racist activists have always worked to alter racist beliefs, because, again, racist ideology is what makes racist acts possible.

I don’t say that we shouldn’t talk about racist beliefs. I just don’t want to see the theory conflated by the practice. This has been done by many pundits, even if not necessarily on this particular platform. If Lovecraft was guilty of the “praxis” side of racism, I haven’t read of it.

Well…that starts to be an issue of what positions of power you’re in. I’m not super-familiar with his biography.

William Marston did some racist shit though, involving his lie detector tests and court testimony. Jill Lepore discusses it in her new biography.

Strangely, the only time I’ve ever seen a naturalistic depiction of a black person in 1940s comic books– that is, neither a minstrel-show caricature nor a white person with darkened skin– appeared in WONDER WOMAN. But that might reflect more on Peter than Marston.

Well, it must have been something of an aberration then. Wonder Woman 19 is filled with vicious, animalistic, sterotyped depictions of black people. That’s much more the norm for Marston/Peter.

Oddly, the deeply anti-Semite Lovecraft married a Jewish woman. She sometimes had to interrupt him in the midst of an anti-Jewish tirade to remind him of her ethnicity.