Well, it’s been a long week. The hagiography has come and gone, the backlash has come and gone, balanced views have been proposed and interest is fading. What remains are protests in the Middle East against the caricature of the Prophet in Wednesday’s issue, and islamophobic violence in France (with one minor but heart-warming exception). One complicated answer that seems to remain, though, is “can an openly anti-racist magazine be racist at times, through carelessness and insensitivity ?” I am probably not in a position to say, but here is a look at one year of Charlie Hebdo covers.

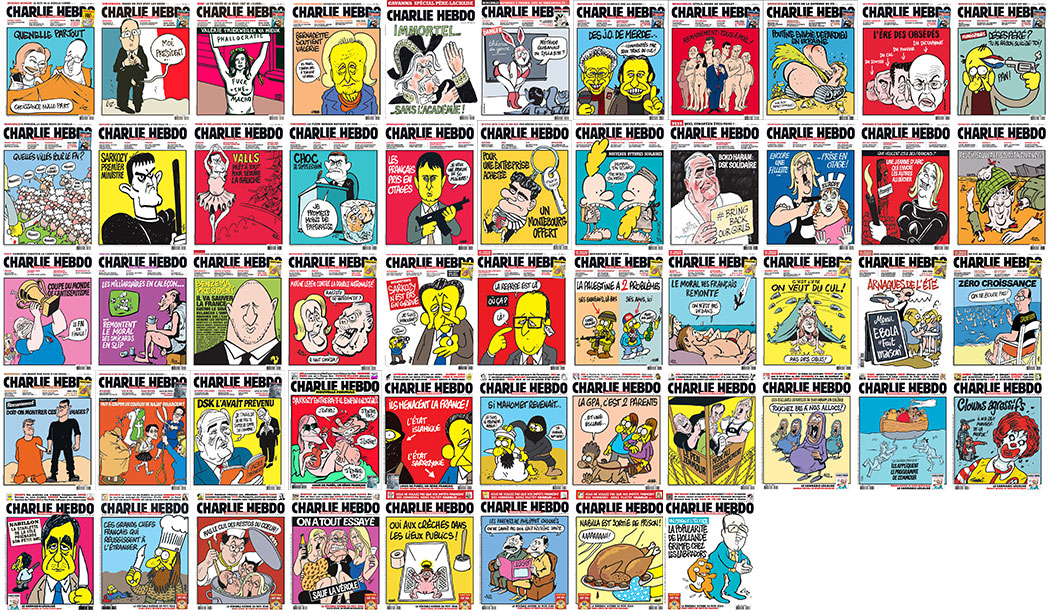

52 pictures, then. From January 8th to december 31st 2014, Charlie Hebdo covered the news, with their now-(in)famous brand of vulgarity and cynicism. The hope is that, with a segment this size, we can investigate the techniques used to represent racial minorities, and especially the Muslim community. After all, they have been constantly under attack, haven’t they ?

Well, not really. Out of these 52 covers, none is directly about Islam or the French Muslim community. In fact only one is about religion, it dates back to December and makes a joke about the far right trying to push Nativity Scenes in public buildings for Christmas. Eight, however, reference djihadism, but more on that later.

So what ARE the covers about, if they’re not about religion? Well top of the list, with eleven covers, is the Le Pen family, head of the far right party Front National. Clearly, they have been Charlie Hebdo’s most consistent targets over the years. The magazine has never stopped shedding light on their hypocrisy, racism and what they see as the self-hurting stupidity of their electorate (many of whom are very poor people who would suffer from the FN’s anti-welfare program). Second is president François Hollande who is also pictured eleven times, though often not as the main subject of the image. Then comes Prime Minister Manuel Valls and other members of his government, who total 8 covers. Former president Nicolas Sarkozy closes the top with seven covers. The rest are about current events, from plane crashes and ebola to Gerard Depardieu’s tax evasion and school reform. So what are we left with to assess the racism of Charlie Hebdo ? Mainly three groups: political figures who are not white, racial minorities among background characters, and the treatment of djihadism.

Political figures

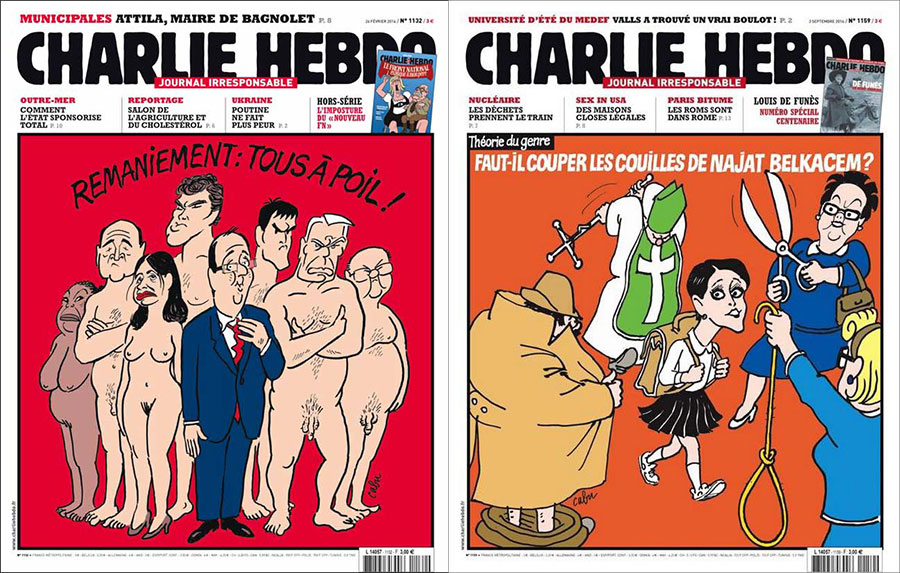

Left: Government reshuffle : they drop it all !

Right: Gender theory : should we cut Najat Belkacem’s balls ?

Only two non-white political figures appeared on the cover of Charlie Hebdo in 2014. Najat Belkacem and Christiane Taubira. Both are simple caricatures, without any racial stereotypes involved. But is the fact that only two non-white politicians are represented a sign of racism in itself? Since members of the government other than Prime Minister Valls only appear on three pictures, two is actually not that bad. And since their newsworthiness derives from being favorite targets of the right, their both being women and non-white says more about the French right than about Charlie Hebdo. Christiane Taubira, however, was the subject of a highly controversial cover back in 2013, so it’s probably worth looking into it.

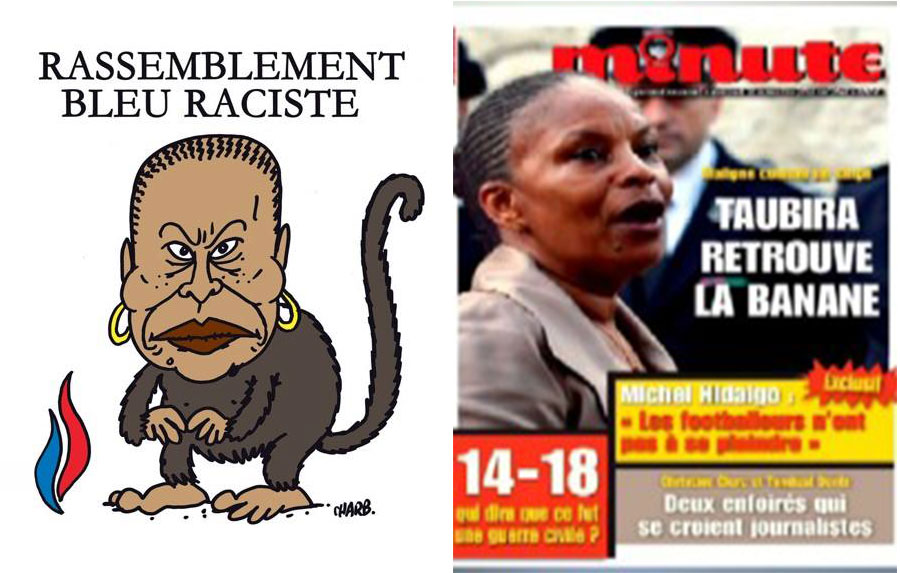

Taubira, a radical leftist and former independentist from Guyana, is Hollande’s Justice Minister. As such, she was in charge, in 2013, of the bill that would open marriage rights to gay couples, which has made her the archenemy of the religious right. It doesn’t take long for the attacks to take on a racist “undertone”, culminating in a nauseating joke posted by a member of the Front National (FN) on her facebook page, showing two photos, one of a baby ape in a pink dress and one of Taubira, with the legend “At 18 months. Now.”

For years, Marine Le Pen, daughter of the infamous creator of the FN, has been working on her party’s image, superficially cutting ties with the most violent branches, and recentering her message on fighting the so-called islamification of France in the name of French secularism. At the heart of the rebranding is the use, on most of the communication, of the expression “Rassemblement Bleu Marine” (“Navy Blue Union” or “Navy Blue Gathering”), instead of the FN name.

When the scandal of the monkey joke broke, Charlie Hebdo immediately used it to point out that, despite all its rebranding efforts, the National Front was still at heart a violently racist movement, as they’d never stopped saying. Above the image of Taubira as an ape, they renamed the super-party “Racist Blue Gathering”. On the left, the red-white-blue flame of the FN served as a reminder that the ties with the movement’s past were far from cut.

Was the racist representation of the minister still a mistake, though ? Some time later, the far right magazine Minute created its own cover on Taubira. “Clever as a monkey, Taubira gets her banana back.” (“having the banana” or however one can translate it, is a French expression that means “to look happy”). When Minute was brought to justice for racial insult, and cited the Charlie Hebdo cover as a precedent, Charlie chief editor (and author of the cover) Charb responded : “[the difference is that] by repeatedly associating Ms. Taubira’s name with the words “banana” and “monkey”, the far right hopes to pass a racist slogan, a colonialist insult off as a popular joke.” It’s been pointed out that in a way, Charlie Hebdo’s image participates in the “repeated association”, and Charb’s explanation of the problem might be a sort of admittance of this. After all, as Charlie cartoonist Luz explained in this interview, in order to be able to push the envelope, the Charlie Hebdo staff has always allowed itself to make mistakes. There are laws in France against racial insult and pushing racial hatred. Unlike right-wing pundits who constantly turn their trials into publicity stunts and themselves into victims of political correctness, Charlie Hebdo has always accepted trials for racism as justice doing its work of sorting out whether they had gone too far this time or not. Which they were found to have, in a very few, but existing, cases.

Background characters

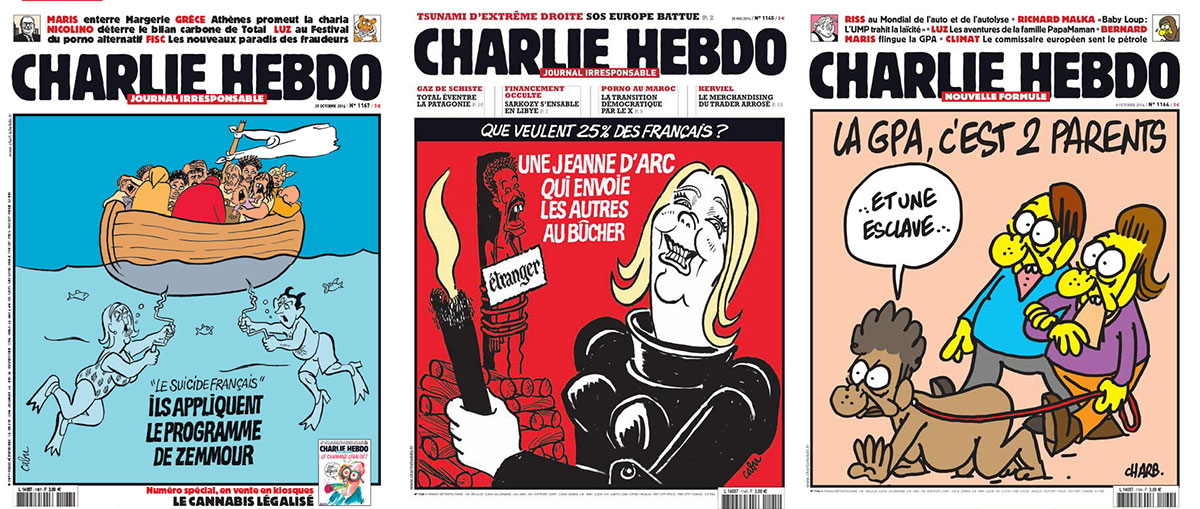

Left: French Suicide: they apply Zemmour’s book’s program

Middle:What do 25% of French voters want? A Joan of Ark who sends others to the fire

Right: Gestational surrogacy: it’s 2 parents. ‘And one slave…’”

Again, only three instances, but they do provide some controversial material. The most benign, by Cabu, shows Nicolas Sarkozy and Marine Le Pen drilling holes in a small boat full of refugees. The people on the boat represent various origins, with some cultural and racial shorthand, but the general tone is one of empathy for the refugees. In the second one, interestingly also by Cabu, the “foreigner” (as his sign says) is represented in a manner much more reminiscent of openly racist caricature. The contrast with the previous image illustrates how Cabu uses racist imagery specifically to illustrate the racist nature of Le Pen’s program. “What do 25% of voters want?”, the legend asks. “A Joan of Ark who sends others to the fire.” The final image, by chief editor Charb, is by far the most shocking. The text explains the image, but doesn’t make it any easier to watch : “Gestational surrogacy : It’s 2 parents, 1 slave”. The subject is clear : is people renting other people’s bodies an ethical hazard? Still, the shock value of the image is unrivaled in 2014, even by the “Boko Haram sex slaves” cover. The reason it is so shocking, however, even to the casual Charlie reader, is because there’s only one like it.

In one of his twitter essays, Jeet Heer defined the risk of using racist imagery as satire. “I think what is true of Crumb is also true of Charlie Hebdo: the anti-racist intent of shocking images blunted & reversed by repetition.” The thing is, contrary to the impression given by small selections of the most offensive cartoons, such shocking images as the “2 parents, 1 slave” are not repeated at all. There is just a handful of really offensive material in a given year, and it’s not the same subject each time. They may value their irresponsibility, but they also know how to manage shock value.

Djihad : the great big joke

Here we are, then. The section where attacking extremists means attacking Islam, which means attacking Muslims, which means bullying minorities. First, let’s get rid of the ones that only mention djihadism to make jokes about Prime Minister Valls. That’s two.

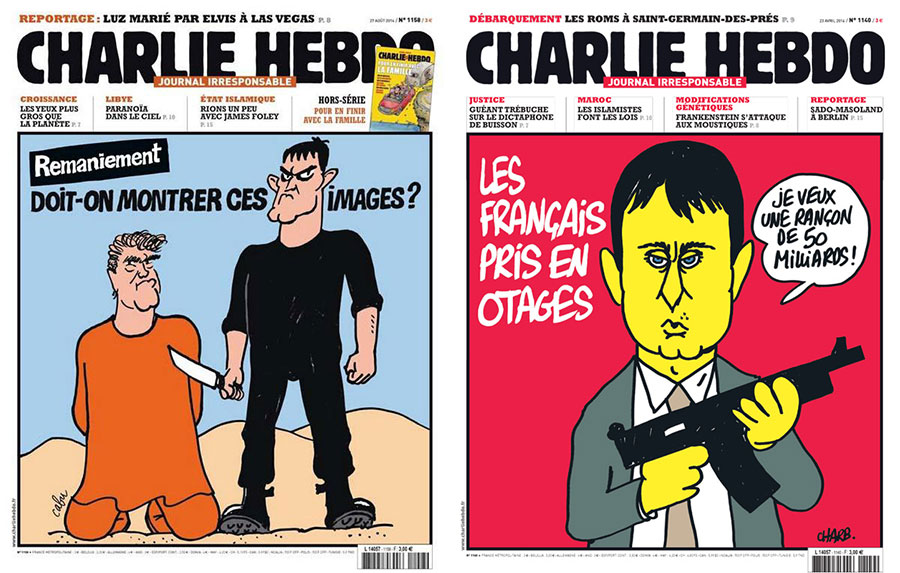

Left: Government reshuffle : Should we show these images?

Right:French hostages : ‘I want a €50bn ransom’

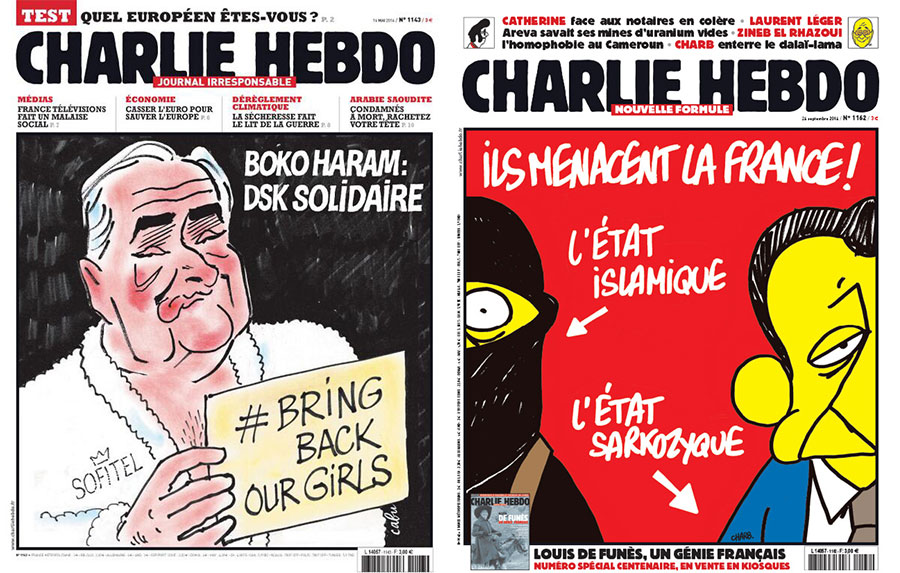

Dominique Strauss Kahn holding a #BringBackOurGirls sign with a lecherous look, or the return of Nicolas Sarkozy compared to the threat posed by ISIS are also only incidentally about djihadism.

Left: Boko Haram : DSK expresses solidarity”

Right:The threat to France! Islamic State / Sarkozyk State”

A strange one is the Titeuf cover. School reforms have inspired to Luz a weird joke where the iconic haircut of the famous (in France) children’s comics character is used as an Islamist’s beard. It may reference child soldiers in war zones, or religion at school, but it’s most probably a purely visual, message-free joke. The second one also blends a favourite newspaper headline with terrorist imagery for a rather benign result.

Left: School reform : ‘Tomorrow, I have Djihad!’ ‘You’re lucky, I have maths!’”

Right: Those French chefs who find fame abroad”

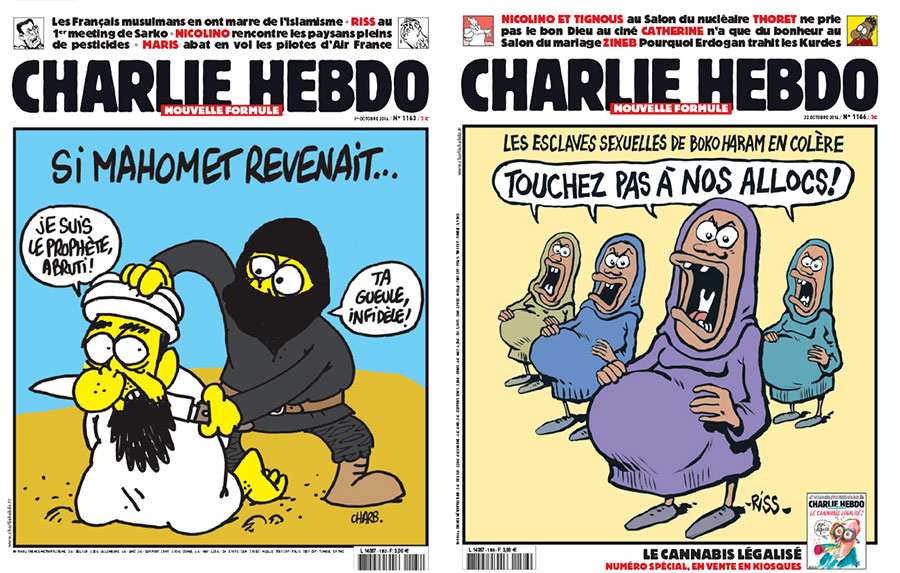

And finally, there are the two covers of 2014 that have been featured in selections of racist Charlie covers. The first one is fairly straight-forward, and is only offensive as it features Mohammad. The joke itself is about how the djihadists have deformed His message so much they wouldn’t even recognize him if he came back today. Which seems far from islamophobic.

Left:If Mohammad came back: ‘I’m the Prophet, you moron!’ ‘Shut up, infidel!’

Right:Boko Haram’s sex slaves are angry: ‘don’t you touch our welfare!’

The second one is the hardest to explain to a foreign audience, because it features two specificities of the Charlie Hebdo humour that here blend awkwardly. The first is the conflagration of two pieces of news : the crimes of Boko Haram in Nigeria, and the attacks on the welfare system in France. The second one is the use of racist imagery in pictures that denounce racism (as seen above with Cabu’s Joan of Ark cover). The French right (and the European right in general) often point the finger at immigrants to explain why the welfare system costs too much. It’s an easy rhetoric because everybody agrees that we spend too much on welfare, but nobody wants cuts to the help they themselves receive, so blaming the usual suspects is a popular choice. Therefore, as Terry Drinkwater summarized on Quora : “Fairly straightforward, innit? The absurdity of raped and pregnant Boko Haram sex slaves acting out the welfare queen stereotype parodies the absurdity of the welfare queen stereotype.” What obviously didn’t help the cartoon to be understood as anything but racist is Riss’s rough and dirty style, which owes more to Reiser than to Cabu and Wollinsky. Little can be said about that, as it seems very much a matter of cultural taste. It does increase the insensitivity of the joke, though, admittedly.

Racism and Charlie Hebdo’s attacks on political Islam

A name that has been missing from most discussions is Zineb El Rhazoui. She certainly isn’t the only immigrant who has worked at Charlie Hebdo, from star cartoonist Riad Sattouf to their Kabyle copy editor Mustapha Ourrad, who was killed during the attack. She is however the magazine’s most virulent voice against political Islam. Looking again at the covers, here is a list of articles penned by El Rhazoui : “Tunisia, on the way to an atheist exodus”, “Morocco : the Islamists make the laws”, “Tunisia : quiet, the police is raping”, “Porn in Morocco : democratic transition through sex”, “When Muslims laugh at Islam”, “Mohammad, soon to be caricatured in Muslim countries?”…

Again, these are just a handful of articles among many that cover America, North Korea, Antisemitism in France, Islamophobia in Germany, etc. This list shouldn’t give the impression that Islam is the magazine’s favourite subject. As Luz, author of the “Charia Hebdo” and “All is forgiven” covers, explained a while back, “As atheists, it’s obvious that living in a traditionally catholic country, we’re going to attack Catholics more than Muslims, and the clergy more than God.” Similarly, Jul said : “It’s much easier to create violent cartoons about Christians, probably because we live in a Christian country. You can’t make fun of a minority religion the way you make fun of the majority one.”

Left: Private school : ‘If you’re nice to me… I’ll take you to the anti-gay protest!’

Right: God out of school : ‘So sick of parent-teacher meetings!’

As a leftist magazine, however, promoting the secularist fights for civil rights in the Muslim world is very much part of Charlie Hebdo’s mission. First, because they feel a connection to the minorities who fight theocratic tendencies in their countries. Unlike in the US, where civil rights were fought for by religious figures such as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, in France they have always been fought for by secularists against the religious right. Just last year, the Catholic sphere organized an incredibly violent opposition to gay marriage, which inspired a flurry of Charlie Hebdo covers on Christianity and homosexuality (see the first image above). The second reason why secularists’ struggles in Muslim countries is an important subject is because it counters the “clash of civilization” narrative that the racist right is trying to impose in France. It is a way of showing that the real struggle does not oppose Christian and Muslim societies but rather civil liberties against theocratic instincts, in every society.

Zineb herself has explained as much in a long response to a Swiss newspaper which had accused Charlie Hebdo of racism back in 2011 (quoting articles she had written while not referencing her anywhere). What is racist, she proclaimed, is to consider that people in Muslim countries are somehow impervious to enlightenment. That holding Muslims to the same level of expectations as Western countries in terms of democracy is asking too much. Herself a civil rights activist who spent most of her life fighting the oligarchic and theocratic nature of the Moroccan monarchy, she certainly feels that the ostracized minority that fights for democratization in Arab and Middle-Eastern countries deserves more support than those who would try to have religion gain the same level of untouchability in France as it enjoys in more pious societies.

Zineb’s response is apparently only available in French, but Olivier Tonneau wrote a “Letter to my British Friends” that explains in length the French radical left’s position on Islam. Charb also wrote on the absurdity of giving religion too big a part in identifying members of French society: “I can’t stand people asking ‘moderate Muslims’ to express their disapproval of terrorism. There’s no such thing as ‘a moderate Muslim’, just citizens with a Muslim heritage, who fast during Ramadan like I celebrate Christmas. They do act: as citizens. They protest with us, vote against rightist idiots… It would be like asking me to respond ‘as a moderate catholic’ just because I was baptized. I’m not a moderate catholic. I’m not a catholic at all”. A statement in which a lot of religious people probably wouldn’t recognize themselves, but one that does explain a lot of Charlie Hebdo’s perceived insensitivity.

So… That’s it. Race – and religion – in Charlie Hebdo’s 2014 covers. It feels a little anti-climatic. Where are all the most offensive jokes? Naked Mohammad? The “Untouchables 2”? Well, they date back to 2013, 2012, and hide disseminated among hundreds of other pictures about DSK’s arrest in New York, Israel bombing Gaza and anti-semites reaping the benefits in France… More airplane crashes, more attacks on the Le Pens, a whole lot of penises and a whole lot of good and bad jokes. You can find them all here. And if you have a hard time finding the worst ones, well the truth is, they were also hard to find at the time. Because Charlie Hebdo, “a glorified zine” as Luz himself calls it, never had a large readership. And it’s perhaps the biggest misunderstanding about France and these cartoons : nobody ever gave a damn about them, unless they saw some political gain in having an opinion.

Unbelievably strong overview and writing. Your work and thought made us all smarter. Thank you for the effort.

As an addendum, here is an open letter that Zineb El Rhazoui wrote in response to the piece by Olivier Cyran, in which she talks (among other things)about what it’s like to be an “incoherence”[une incohérence] to monolithic declarations about race, ethnicity, allegiance, and identity when it comes to Charlie Hebdo. I’m guessing you already know of this piece, but every day brings something new to me.

Hey Josselin; you say that secularists have always been the one fighting for civil rights in France. I just wonder…does the Terror ever come up in these discussions? France seems like a country which has a pretty iconic historical moment of indisputably, ideologically atheist oppression. Does anyone ever talk about that, or is it too long ago?

^^ Meant to say “here is a translation of” the Dec 2013 Zineb response I think you were referencing. Poor morning brain; poor morning writing.

Thank you! Great analysis of our beloved journal CH.

Maybe that douche B of J. Canfield can start to understand something about Charlie…

Hey Peter, thanks for the kind words and thanks for the link. This is the piece I was referencing, and that I thought hadn’t been translated.

Noah, I have to admit to an oversimplification over the secularists’ part in civil rights struggles. What I meant is that it’s a widely shared narrative, especially among the left, but the truth is probably more complicated. Simone Veil, the Health Minister who passed the Abortion Rights bill in the 70’s, was an agnostic Jew. The Front Populaire, the first leftist government of France, passed a lot of important laws that changed French society, but they didn’t open voting rights to women because they feared that women were too influenced by their priest, who were (believed to be mostly) conservatives. I’m sure more examples can be found to complicate my initial statement.

About The Terror, I’d say it just doesn’t come up, but mostly, it is seen as a fairly unidealogical development. That war with all the surrounding monarchies, and against Catholic resistants in the countryside, coupled with escalating conflicts between revolutionary factions, led to and idealogical panic and escalating craziness that betrayed the early spirit of the revolution, but didn’t tarnish its legacy. Since a lot of victims of the terror were fellow revolutionaries, it is not seen as a specifically atheist form of opression. I’m not sure I’m actually answering the question, though. :-)

“That war with all the surrounding monarchies, and against Catholic resistants in the countryside, coupled with escalating conflicts between revolutionary factions, led to and idealogical panic and escalating craziness that betrayed the early spirit of the revolution, but didn’t tarnish its legacy. Since a lot of victims of the terror were fellow revolutionaries, it is not seen as a specifically atheist form of oppression. ”

Wow. Okay. That seems like an impressive form of double think if that’s actually the standard line. Religions do that too, I guess (the inquisition isn’t really Catholicism, or what have you) and there’s certainly value in saying, “this is not what we stand for, and we repudiate it.” But it seems like if the Terror doesn’t make you take a moment at least to think about the possible downsides of militant atheism…

The revolutionaries weren’t atheists in the main. They were anticlerical, which is not the same thing. Most of them were deists.

Josselin, congratulations on a fine article.

I sense I’m going to betray a form of patriotism I didn’t think I had, but what I found about the atheist part of the terror is this :

Two revolutionary groups, named the Enraged and the Hebertists (called the Exagerated by other revolutionaries), wanted an escalation of the conflict, at home and abroad, a total revolutionary war. They used atheist and secularist laws to harass the country clergy, knowing that it was the best way to stir rancour among the people. It went from bad to worse for a year (september 1793 – september 1794), until Robespierre decided they had gone way too far and had his group, the Jacobites, accuse the Exagerated of… all the crimes they had been commiting. A majority of the Assembly found them guilty, the Exagerated were arrested and put to death. By people who weren’t militant atheists and who continued killing each other after that. Of course, this boils down to “violent people used atheism as a justification for their violence” which is… a familiar defense.

Also, there’s no denying that, apart from the violence, a lot of stupid history-denying decisions were made in the name of atheism during the revolution.

It’s interesting — I won’t say “telling” — that the Charb cover of 1 October has, in my experience, not been presented, discussed, or attacked. Not only is it the most recent “Mohammed” cover; it is also the most explicit, calling him and his status by name (and being killed). It’s similar to the “It’s hard being loved by idiots” cover, but even more direct.

Why would this be the case, this pass for the most recent version of Mohammed on the cover? Is it because the target of the cover is so clearly the hooded ISIS figure? Or is it at all related to how Charb draws, where everyone of every “race” has the same face, the same bulbous nose? Could more negative reactions rest entirely on the absence or presence of “the hook”?

This is a great service to the debate, thank you.

Josselin, you mentioned Charlie Hebdo cartoons about the Gaza invasion. Was the magazine generally critical of Israel’s policies toward Palestinians? I just read a blog post by pro-Palestinian writer Norman Finkelstein (http://normanfinkelstein.com/2015/01/15/ich-bin-der-sturmer/) in which he compares Charlie Hebdo to the Nazi magazine Der Sturmer and notes that Der Sturmer’s editor was sentenced to death at Nuremberg. I usually admire Finkelstein, but that sounds like a really, really stupid comparison to me.

(It’s actually not Finkelstein’s first comment on cartoon racism–he devoted some space in his book Beyond Chutzpah to mocking the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia for calling some cartoons anti-Semitic when they clearly weren’t. He’s also collaborated with the cartoonist Carlos Latuff, who has been accused of anti-Semitism and compared to a Der Strumer cartoonist for comparing Israelis to Nazis.)

Jack, I’m not absolutely sure, but I would say that, like a lot of European leftists, they’re highly critical of Israel’s policies. They’re also very vigilant of how this can turn into anti-semitism back in France.

One of the 2014 covers I didn’t discuss (and maybe I should have) is this one : http://p4.storage.canalblog.com/41/27/177230/100277968_o.jpg

It reads “Palestine has 2 problems :

Its enemies there : ‘Israel shall vanquish!

Its friends here : ‘Death to Jews!'”

A lot of articles whose title appear on the 2014 covers are also about how some people in France, namely the radicalized comedian Dieudonné and the so-called philosopher Alain Soral, turn the emotional response to Israel’s actions into anti-semitism.

This is the best-informed piece on Charlie Hebdo to appear at HU thus far. I predict that it will consequently be the least-discussed.

Maybe no one’s mentioned that cartoon because it seems straightforward and kind of boring? Religious leader upbraiding followers for failing to adhere to the religion; I don’t know. I guess that’s what you’re saying, Peter, that it’s relatively uncontroverisal, and therefore ignored. But I’d point out that it’s ignored by both sides, right? No one is interested in a fundamentally uninteresting cartoon.

You seem to be losing out on that guess so far, Franklin; comments seem fairly brisk.

it is a really, really great article. And of course i would comment that reiterating the fact that Charlie Hebdo has been a solidly leftist magazine doesn’t change the kind of pawn that its images and its dead writers can become in larger debates on how to deal with “the Muslim problem.”

I received, by request, from a French friend, some of CH’s recent published comics about Palestine and posted them here:

http://freedomfunnies.tumblr.com/post/108254709655/cartoons-from-charlie-hebdo-on-palestine-a-small

Did everyone see the Telegraph article on the founding editor of CH corspe-blaming Charb? http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/11346641/Charlie-Hebdo-founder-says-slain-editor-dragged-team-to-their-deaths.html

Thoroughly tasteless and insensitive, but, as Ive maintained, that’s keeping in the CH spirit. Also, apparently not every leftist in France loves CH, for whatever that’s worth.

“A founding member,” my apologies. And he might have Lord knows what other baggage with CH.

Thanks, Josselin and Ethan!

Yes, Delfeil de Ton’s attack on Charb is really flabbergasting. It denies the other contributors any sort of personality and most irritatingly, seems to forget that CH was at least as offensive in the 70’s as it is now. To me, who didn’t live through that decade, the covers of the time certainly are more shocking.

Also, you are absolutely right that not everybody on the left is a big fan of CH. Most probably find them more vulgar than problematic, some are attached to political correctness, and some, such as popular punk cartoonist Tanxxx, find them racist, macho and really just a bunch of assholes.

A center-left literary critic named Eric Naulleau once said about Hara Kiri : “when I was a teenager, people on the left read either Charlie Hebdo or Pilote. I was always more of a Pilote fan.” Again, I came later, but I guess I’m also more of a Pilote fan, and I think I’m in the majority on that one.

Eh, well, since Franklin wanted more comments:

I really like this piece, and it’s very helpful in understanding Charlie Hebdo, I’d agree. I somewhat resist the idea that it’s the “most informed”, in some absolute sense. It’s certainly the one that looks most closely at the history of the magazine. But I feel like Janell Hobson’s piece was very informed about the workings of racial representation in an international context, and Marguerite Dabaie’s piece discussed the context of Muslim and Arab restrictions on free speech in the Middle East which obviously this piece doesn’t touch on.

I feel like a lot of the discussion of Charlie Hebdo has focused on “context”, in a way that suggests there is only one context, or that the truth of the cartoons will be made manifest if only the right expertise is used to view them. (I feel like this piece presents the cartoons that way.) But there can be many possible contexts for viewing art, and many kinds of knowledge that can be useful or illuminating for doing so. Again, I think this piece is great, but I don’t think Josselin’s knowledge of the history of the magazine, or his close look at its last year, needs to preclude, or trump, other kinds of knowledge, or other discussions.

Indeed, the whole point of quoting a lot of people, and showing every image even when they didn’t feel problematic, is because I didn’t want to be another “white guy that explains to you what is racist or not”.

I think the reason the covers were more offensive in the 70’s and 80’s is because it was at the time a purely French affair, in which freedom of speech was infinitely more recognized than the minorities it might offend (even if, politically, the magazine defended these minorities against rightist policies and police brutality). There is a recognition now on the part of the cartoonists that they don’t work anymore in the isolated cultural context I tried to describe here. Le Monde’s house cartoonist Plantu stated that Charlie-Hebdo-style caricature was becoming more and more problematic as the Internet made their broadcasting in other cultural contexts possible. The CH staff decided that taking into account every form of sensitivity on the planet was not an option for them and chose to keep doing their own thing on their little corner of Earth, but this decision doesn’t change the fact that their work now needs to be analysed from a global point of view, which I certainly can’t do.

At the linked piece: “Scholarship on comics and cartoons can help us understand the meanings of Charlie Hebdo in important, vital ways that simply skimming over a few cover images from the magazine will never do.” That’s not to say that “there is only one context, or that the truth of the cartoons will be made manifest if only the right expertise is used to view them.” That’s to say that informed analysis trumps misinformed analysis.

Right; there’s a rhetorical disavowal. But he only provides one interpretation, and presents it as being the result of the voice of comics scholarship. That ends up working to use authority to underline his own reading, rather than showing how comics scholarship can help complicate or add knowledge to different potential readings. Or at least, that’s how it came across to me. If the point was informed vs. uninformed, then there should be some examples of uninformed from different points of view. If the point is to use “comics scholarship” to buttress one particular reading, then you get the article you’ve got.

I also found his readings pretty banal. It just pretty much reiterates the “free speech martyr” interpretation, which lots of people who weren’t especially informed picked up immediately following the shootings. It interestingly contradicts Josselin at some points as well — most notably maybe by suggesting that the cartoonists were central to French culture, whereas Josselin argues that CH was a much more marginal publication, largely off the public radar in the normal course of things. Josselin’s piece may be a rebuke to Jacob, but it seems like it’s as much a rebuke to Mark.

“The CH staff decided that taking into account every form of sensitivity on the planet was not an option for them and chose to keep doing their own thing on their little corner of Earth, but this decision doesn’t change the fact that their work now needs to be analysed from a global point of view, which I certainly can’t do.”

Their work was assessed and they were given a death sentence.

Of course that’s how it came across to you – you have a heavy investment at this point in presenting Jacob Canfield-style ignorant outrage as one possible valid interpretation among many.

And you have an interest in seeing one particular interpretive frame as the most valid, and the most informed.

There’s a piece that could be written about how comics studies brings depth to different interpretations, and how that works. That isn’t Mark’s piece, unfortunately, despite the fact that it flatters your particular preconceptions.

I said most informed, you said most valid. And this is a constant pattern with you, to misattribute motives and claims to people you don’t agree with until they flatter your preconceptions about their arguments.

Yes, yes, you think I write in uniquely bad faith, I know. That’s fine; I don’t find you an especially honest interlocutor either…but so it goes.

Maybe to try to talk about something other than Franklin’s and my mutual antipathy….

The Gestational surrogacy image; I have trouble seeing that as anything but racist. Thoughtlessly so, rather than intentionally so, perhaps, but…unless I’m missing something, the only reason to make the slave black there is because that makes the image more shocking/titillating. Using racist imagery because it’s fun, or gets a reaction — that seems like it’s just enjoying racist imagery, which seems at least somewhat racist. It’s not even criticizing racism, right? It’s just using shocking racial imagery to talk about something else, because that will cause raised eyebrows/outrage.

Josselin’s point that they didn’t do this all that often is well taken…but the occasional racist image is still racist, it seems like, even if the use of those images didn’t define the magazine month to month.

Josselin, am I missing something in how that image is used?

Noah, you’re pulling me on a path I’m not super comfortable treading, coming from a culture where issues of color are less (and less deeply) discussed.

Was making the slave black useful to the satire ? My initial impression was that Charb was intent on expressing how gestational surrogacy raises issues of race relations, after an Australian couple refused to take the handicapped child their Thai surrogate mother had borne. In which case having the “slave” voicing the issue felt somewhat “elegant” (given the circumstances).

On second thought, though, the image could actually be making fun of conservatives calling gestational surrogacy “basically slavery”. In which case making the slave black is little more than another case of “visual shorthand” and way less elegant.

Thanks Josselin. If it’s not clear to you what’s going on, it seems like at the least it’s a careless use of really charged imagery.

About a few imagery that may shock [as a French] :

On the “gestational surrogacy”, I don’t doubt that it is to make a visual shorthand. The Australian couple story did not get much media attention in France and was several months before this cartoon, so forgotten by then

You need to remember though that outside the Overseas Territories, the “slaver” past of France is not much of a political issue ; almost no one in “Metropolitan” Franceis a descendant of slaves. Therefore, using “slave” imagery in the cartoon is only midly shocking. Slave = Black.

On the Boko Haram, I would not give it a far-fetched explanation about the Right being so paranoid that they would be afraid of paying “alloc” to Boko Haram sex-slaves. I think it is the much more basic “let’s put together 2 events from the news with no link whatsoever”. Sometimes it works perfectly [the “governement reshuffle” one is outstanding], sometimes it does not work well [“French hostages”], and sometimes it just does not work at all. And when, like in this case, they play with victims, it makes it incredibly tasteless and bad ; though not racist.

As a final note, one should in my opinion be wary about “cultural racial stereotypes.” France has a different history than USA and thus some “stereotypes” when drawing people are seen as “acceptable”, while other way of drawing people would shock French. As an example, the Arab guy depiction in the Joan of Arc cartoon is extremely racist by French standard [obviously on purpose] but I am not sure [I can be wrong] it would be quite as racist as seen by a non-French without an history of North-African colonisation. On the other hand, France having a different history with regards to slavery and “black facse”, the Boko Haram sex-slaves depiction is not “racist” by French standard, though indeed as everything Charlie Hebdo they are depicted as ugly.

Thanks Narwhal.

“Slave = Black”

Right; I think that kind of easy equation is in fact racist, though. Turning black people into their exploitation and erasing their individuality — that’s a racist thing to do. The fact that it’s done casually and stupidly rather than with a definite white supremacist agenda doesn’t mean it’s not white supremacist; it’s still using black people’s pain and exploitation for the (casual, stupid) needs of white people.

Same with Boko Haram. A tasteless, bad, careless cartoon using offensive racist tropes because those racist tropes are cool/funny/shocking kind of ends up being racist by default. At least in my view.

Again, I think it’s definitely worth pointing out, as Josselyn does, that this sort of thing was the exception rather than the rule, which certainly I think contributes to the sense that the racism (especially towards black people as opposed to Muslims) was casual and dumb, rather than thought through and intended as some sort of programmatic statement.

I’m interested in the idea of tactics. It is hardly a far-fetched statement to say that, at least sometimes, satire wants to make a point through mockery, and CH seems to be no exception. It seems quite likely that the magazine was targeted for having a high ratio of symbolic payoff for minimal security risk- but it also seems likely that, since their offices were firebombed, CH did have reason to think of itself as operating in a political theater in which violence was a potential outcome. They may be heroes, then, for consciously risking their lives to make a statement about free speech- they may have been punching down, but they were also sticking their necks out. But what does it mean that they did so many sloppy cartoons? We’re they sloppy on purpose? Was it a tactic? Or, if they failed to think strategically, is that something that cartoonists combatting fundamentalist Islam should think about more in the future?

Lets say it was proven beyond doubt that Charlie Hebdo was racist and specifically islamophobic. How then should we represent the attack in Paris which resulted in ten dead Charlie Hebdo employees including its editor, three law enforcement officers, and four jews.

Could we justify the attack under a theory of cultural re-equilibration – in which the wrongs of Charlie Hebdo in its racism and islamophobia triggered a predictable reaction from members of the group being targeted.

Many have suggested there is a direct parallel between the editor of Der Stürmer being sentenced to death in the Nuremberg Trials and the deaths of the employees of Charlie Hebdo. That is like Julius Streicher and Der Stürmer, we hear, Charlie Hebdo has been found guilty of crimes against humanity (racism & islamophobia similar to Der Sturmer).

Well, I think Jacob’s piece addressed this pretty clearly. You can criticize the cartoons for being racist (or for that matter for being sloppy and careless and maybe not especially well done) without condoning the killings. Making bad cartoons, or racist cartoons, is not any kind of excuse (to say the least) for murderous violence.

“Many” have suggested that there’s a parallel with the editors of Der Sturmer? Seriously? That sounds pretty crazy to me. Do you have links?

Bert – That Charb Mohammed cover shown above looks like it was done with the criticisms of the earlier cartoons in mind, to focus more precisely on religion and jihadism. The use of yellow for skin tone in particular seems like a deliberate move.

Noah – Yeah, I couldn’t believe it either – http://www.my.telegraph.co.uk/pragmatist/pragmatist/15188269/what-do-these-two-magazines-have-in-common/

– About my earlier comment, I should have said “slave = black”, not the opposite ; if you want to represent a slave in France, -(s)he has to be black. Native-American slavery was practiced by the French in a very limited way both in scope and time.

I won’t defend the Boko Haram cartoon, which is in my opinion their worst in years, and clearly “crossed the line”.

– “Lets say it was proven beyond doubt that Charlie Hebdo was racist and specifically islamophobic.”

This is very definitive. None of the French [national/significant) “anti-racist” associations would say the same.

The MRAP, which did strongly disagreed with C-H decision to publish the Danish caricatures in 2006. Nevertheless, they declared in 2011 that they “thanked Charb for his support to our movement and for his anti-racist action. After the cartoonists were killed, the MRAP said “Charb, Wolinski, Cabu Tignous and their followers were anti-racists. They will remain in our memory as they were there for the combat for the Right of Man”

The LICRA is staunchly behind Charlie Hebdo and sent inflamatory press release, though indeed the LICRA has been called “islamophobic” at times.

SOS Racisme, which cannot be in any way suspicious of islamophobia, called Charlie-Hebdo the “most anti-racist weekly of this country”.

http://www.europe1.fr/mediacenter/emissions/europe-midi-votre-journal-wendy-bouchard/videos/charlie-hebdo-est-le-plus-grand-hebdomadaire-anti-raciste-2341899

If you understand French, this one is golden. The head of SOS Racisme can be heard saying “Every week in Charlie Hebdo, every week half their content is against racism, against anti-semitism, against hate against muslims. Some people, because of one cartoon that does not please, say “yes but…”. There is no “but” […] they were anti-racists”.

The GISTI, less well-known but in my opinion the most efficient on the legal front, made a vibrant testimony on how C-H shared their fight and cooperated with them and “thanked” the dead cartoonist for their support.

The CRAN indeed did not make specific declaration on whether C-H was or not racist, but followed up on #JeSuisCharlie

Maybe C-H is indeed racist. Maybe the local association are blinded due to the horror of the events. Yet, isn’t it a bit presumptuous to believe that C-H was “beyond doubt” racist based on an handful of handpicked/”failed” cartoons and on a few individual voices like Olivier Cyran’s when almost all the people “on the field” and aware of the local situation / culture / context say not only it is not “racist”, but that it is the “most anti racist” ?

Narwhal, thanks for the list of links, it’s a great resource.

The starting point of the article was that CH was undoubtedly anti-racist but could maybe be inadvertently racist at times through carelessness, by taking their own progressism for granted. Tne important point I think is that they don’t so much take it for granted as choose not to care so much. Their job is to push the envelope, and they accept that crossing the line (and be tried for it) comes with it.

My feeling, though, is that they never really used these trials as publicity stunts. They took them seriously, and always spent more time debating the issue than hiding behind “humor” the way Dieudonné always does.

I’m pretty convinced that the racist content of the cartoons in question was unintended. It does seem like they chose on occasion to provocatively attack political Islam, and by doing so made themselves a tragic target- not once but at least twice. Is this accepted in France as a proper approach to anti-racism? I think it is fair to say that they baited the murderous jihadis who, well, murdered them. The outcome of their cartoon (not to say they planned this – quite the opposite) was not only ;martyred journalists, but attacks on both Jews and Muslims, a hypocritical outcry by Western leaders, and talk about increasing rather than decreasing pressure on Muslim states abroad (although not Saudi Arabia, in most cases). Is this an intended legacy?(

I’ve seen folks other than Cyran say that they found CH’s cartoons at times islamophobic. I’m pretty sure you could find a long list of people who would declare Christopher Hitchens anti-racist. fwiw.

I think Josselin makes a good point. In the American context, at least, the rhetorical move, “I am not racist,” very often means, or precedes, the arguments, “therefore, when I say or do something racist, that’s okay, or doesn’t really count.” It sounds like there was a certain amount of that here; a conviction of being on the right side leading to an assumption that they were justified in using imagery that for someone less righteous might be a problem.

That doesn’t preclude them being anti-racist in certain situations, either. White abolitionists in the U.S. could, and did, say some racist shit.

Thanks for the replies.

How did the JeSuisCharlie campaign get started – was it a popular movement or something else?

It seems that the JeSuisCharlie campaign was like a red flag to a bull for some because they saw it as a pro – racist, pro – islamophobic, pro – support for western govs. campaigns in the middle east totem … and I think this was to a large degree responsible for much of the intense energy in the JeNeSuisPasCharlie campaign and the JeSuisAhmed campaign … there is even a false flag conspiracy theory now claiming it was an inside job … and all this has almost completely clouded the fact that there was an act of terrorism in Paris in which many people died.

Hence the question of what exactly Charlie Hebdo was and the question of the nature and possible range of interpretations of the cartoon is incredibly relevant and important.

Personally I have been persuaded that the cartoons were not racist or islamophobic but I recognise the claims made.

The other question concerns what constitutes a label of islamophobia. We accept as par for the course atheist criticism and attacks against Christianity. If the same criticism and attacks were directed towards Islam would this lead to a valid claim of Islamophobia?

I talk about why attacks on Muslims can be racist here. Anti-Catholicism, in particular, has also been racialized in the British context in the past. So as with so many things, it depends on the context.

My impression was the the I am Charlie meme was the result of many people identifying strongly with the slain cartoonists. I talk about that some here.

Ps someone mentioned the latest cartoon of the prophet Muhammad has a yellow skin whereas before it was brown? That if confirmed would be interesting.

No, there hasn’t been any color change. This week’s cartoon has brown skin, as Luz always drew it . Charb’s characters, on the other hand, are overwhelmingly yellow, be they European, Arab, Middle-Eastern or Asian.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | U.K. distributor Impossible Books is closing - Robot 6 @ Comic Book ResourcesRobot 6 @ Comic Book Resources

I forgot to thank you for this article Josselin – it this type of inclusive view that was missing elsewhere (and involves a lot more work). In surveys one has to take representative samples. Then one has to analysis without pre-judging the results. By trying to prove one thing or another thing one tends to get the result one wants to prove.

Pingback: Charlie Hebdo updates: a year of covers and Publishers Weekly — The Beat

some gave a damn about them, enough to provoke this piece, and the piece that immediately provoked it http://posthypnotic.randomstatic.net/charliehebdo/Charlie_Hebdo_article%2011.htm

Pingback: Links der Woche 3/15: Charlie, El Eternauta, Star Wars | Comicgate

As an American, I find the entire Charlie Hebdo discussion in Europe very stimulating. Cultural difference is so complex that almost any opinion ends up being rendered sectarian or ethno-centric. As a life-long student of French and French culture, and old enough to remember some of the 1970s-style caricaturing to which Josselin Moneyron refers, and based on personal taste in the 1970s, I was very dismissive of this French form of self-expression, as over-the-top, especially since it seemed to try to make a point that even the French didn’t seem to think was a big deal. The range of what is considered “good taste” mattered to me then. Now good taste vs. bad taste seems to be globalized, radicalized and polemicized to the point that what’s considered bad taste will get you killed. My own country’s thirty-year hard turn to the right constitutes one of the on-going injuries to world public opinion about acceptable free speech. My people are extremely under-educated regarding human rights and humanitarian law, the terminology so essential to this discourse. Thank you, Moneyron et al for this discussion.

Pingback: Greater Minds: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie rejects censorship | Cockburn's Eclectics