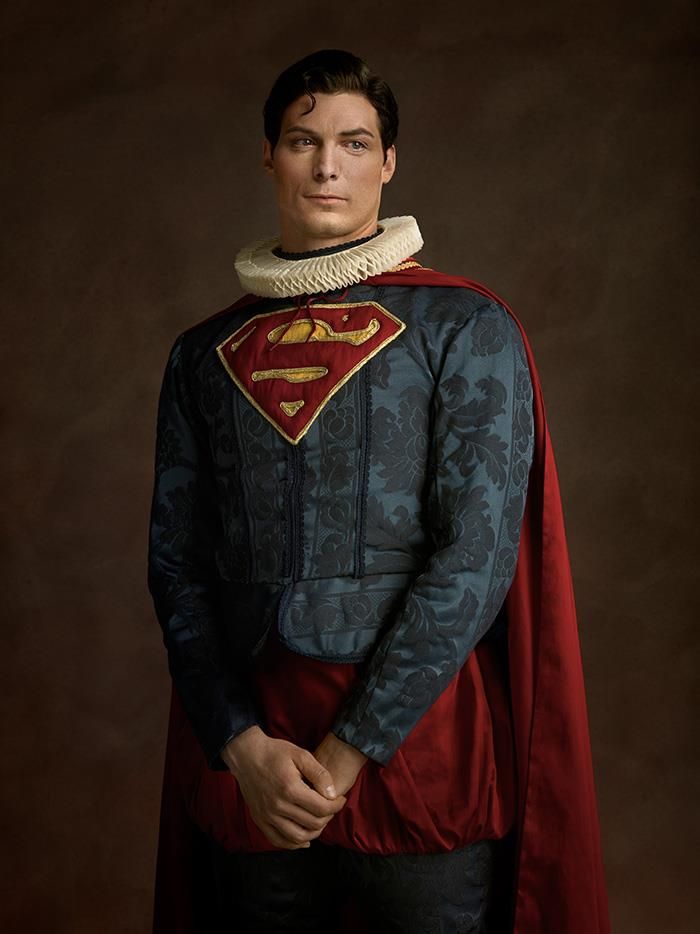

art by Sacha Goldberg

Superheroes didn’t begin in June 1938 with Action Comics #1. They didn’t begin with Superman’s crime-busting predecessors of the 1930s pulps either. Superheroes have a sprawling, action-packed history that predates the Man of Tomorrow by decades.

A century before Krypton exploded, the Grey Champion was confronting redcoats in the streets of colonial New England, while the monstrous Jibbenainosay scourged the Kentucky frontier. Spring-Heeled Jack was leaping English stagecoaches in single bounds as Dr. Hesselius administered to the victims of vampire attacks. Add to this Victorian League of Justice the super-detective Nick Carter, a man with the strength of three, surpassed only by Tarzan’s jungle-perfected physique and the Night Wind’s preternatural speed and crowbar-knotting muscles. While the Scarlet Pimpernel was assuming his thousand disguises, the reformed Grey Seal and Jimmy Valentine were turning their criminal prowess to good as modern Robin Hoods.

By 1914—the year Superman’s creators were born—the superhero’s most defining characteristics were already long-rehearsed standards. Secret identities, costumes, iconic symbols, origin stories, superpowers, these are all the domain of the first superheroes. Some of these very earliest incarnations are startling full-blown, some reveal fragmentary foreshadowing, but all are essential to understanding the century-long evolution of the formula that did not begin with but culminated in Superman.

I cover this terrain in On the Origin of Superheroes, but readers should explore it for themselves. So here’s a tentative Table of Contents for “Supermen Before Superman, Vol. 1, (1816-1916)” a would-be collection of the original 19th and early 20th century essentials:

1. Manfred, Lord Byron 1816

Though the poetry-spouting “Magian” isn’t the first sorcerer of adventure lore, he is the first to embody the moral complexity of the post-Napoleonic anti-ish hero type (and, yes, he has sex with his sister).

2. “The Gray Champion,” Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1835

An old, craggy-looking guy, but a great rabble-rouser. His superpower is inspiration! (Also, his literary sister, Hester Prynne, is the first character to sport an identity-defining letter on her chest.)

3. Sheppard Lee, Robert Montgomery Bird, 1836

The guy’s soul can change bodies. Just give him a non-moldy corpse and he’s good to go.

4. Nick of the Woods, Chapters III and IV, Robert M. Bird, 1837

A homicidal schizophrenic hell-bent on murdering Indians in the spirit of Manifest Destiny. He’s Batman in buckskins.

5. “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Edgar Allan Poe, 1841

The proto-Sherlock and so the original super-detective.

6. The Count of Monte Cristo (excerpt), Alexandre Dumas and Auguste Maquet, 1844

A wrong-avenging master-of-disguise passing along the racial divide, what’s not to cheer?

7. Les Miserables (excerpt), Victor Hugo, 1862

The guy can pick-up a horse-cart single-handedly. I think it was radiation from the social Gamma bomb of the French Revolution.

8. Green Tea, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, 1872

The original occult detective, with a lethal dose of Orientalism.

9. “How Robin Hood Came to Be an Outlaw,” from The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, Howard Pyle, 1883

Yep, Robin Hood. The original noble outlaw.

10 .Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Friedrich Nietzsche, 1883

Nothing superheroic about the ubermensch, but he is the genre’s namesake.

11. Spring-Heeled Jack, the Terror of London, Alfred S. Burrage, 1885

The first Bat-Man, plus the guy has a magic boot and dresses like Mephistopheles.

12. Nick Carter, Detective: The Solution of a Remarkable Case, Frederic van Rennselaer Dey, 1891

Some Captain American level super-strength here, but mostly bare-knuckled detection. No sitting around solving crimes from your French hotel room.

13. “The Ides of March,” E. W. Hornung, 1891

The original Sherlock-flouting gentleman thief, whose spawned a legion of do-gooding imitators.

14. “A Retrieved Reformation,” O. Henry, 1903

More of a supervillain again, but check-out the tropes: alias, dual identity, self-sacrifice, signature skill.

15. “The Hunt for the Animal,” “The Fiery Cross,” from The Clansman, Thomas Dixon, 1904

Okay, this one I deeply apologize for, but (as I’ve discussed plenty elsewhere), he defines the genre.

16. Man and Superman, George Barnard Shaw, 1904

Again, can’t ignore the translated source of the genre namesake.

17. “Paris: September, 1792,” chapter from The Scarlet Pimpernel, Emmuska Orczy, 1905

Just another cross-dressing socialite secretly using his wealth for aristocratic good.

18. “The Nemesis of Fire,” Algernon Blackwood, from John Silence, Physician Extraordinary, 1908

The first occult detective with occult powers–even if he is more sympathetic to werewolves and Egyptian fire demons than the moronic Brits they haunt.

19. Under the Moons of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1912

Find yourself on a mysterious alien planet that gives you super-strength, sound familiar?

20. “The Height of Civilization,” chapter from Tarzan of the Apes, Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1912

First pulp hero actually called a “superman.”

21. “A Midnight Incident,” “The Frame-up,” “A Law Unto Himself,” chapters from Alias the Night Wind, Frederic van Rennselaer Dey, 1913

The first mutant, a cross between Quicksilver and the crowbar-bender of your choice.

24. “The Gray Seal,” Frank L. Packard, 1914

His fingertips seem to have mutant sensitivity, but mostly he’s another urban Robin Hood.

25. Herland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 1915

Paradise Island minus Wonder Woman (and the yellow wallpaper).

26. Doctor Syn: A Tale of the Romney Marsh, Russell Thorndike, 1915

A vicar by day, Scarecrow-costumed avenger by night, plus there’s that whole pirate backstory and prequels.

27. The Iron Claw, Arthur Stringer, 1916

The movie is lost, but the Laughing Mask still debuted in newspaper at the time, doing his mild-mannered routine with his boss and fiance while secretly fighting criminals at night.

Okay, so maybe that’s more one volume’s worth of texts, but this is still in the dream-book stage, and with the magic of unpaperbound e-books, why not?