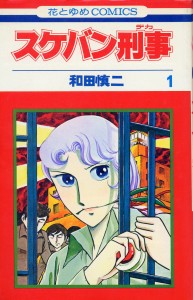

In 2010 I wrote a post about one of my three favorite manga/anime/TV/Live action movie series, Hana no Asuka-gumi. Asuka is indeed a righteous girl gang series, but it is not the oldest, nor the most successful. That honor has to go to what is one of the most awesomely outrageous series ever made, Sukeban Deka.

In 2010 I wrote a post about one of my three favorite manga/anime/TV/Live action movie series, Hana no Asuka-gumi. Asuka is indeed a righteous girl gang series, but it is not the oldest, nor the most successful. That honor has to go to what is one of the most awesomely outrageous series ever made, Sukeban Deka.

Life has not been kind to Asamiya Saki. At 16, she is doing time in a juvenile detention center for various crimes, when the police come to her with a nefarious deal – her mother is on death row for the murder of her father. If Saki works for the police to infiltrate high schools and root out criminal organizations, they’ll take her mother off death row. Saki agrees and becomes the Sukeban Deka – the Deliquent Detective.

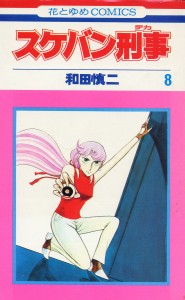

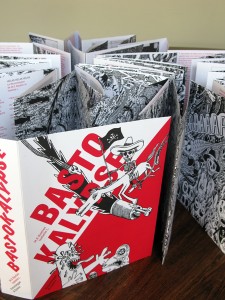

The manga series, which ran from 1976 – 1982 in the pages of Hana to Yume magazine, was the first, the darkest and in many ways the craziest, of the three massively popular gang girl series. The manga spawned a live-action TV series that ran for three seasons from 1985-1987, in which the name “Asamiya Saki” becomes a title passed down through generations from the first Asamiya Saki to her successors. These were followed by two live-action movies in 1987 and 1988, in which two of the actresses that played Saki in the TV series reprise their roles. In 1991, an anime OVA, which covers the first arc of the manga was made (and for the finale alone, as Saki fights the evil high school crime leader on a burning oil tanker in the middle of the ocean, it’s totally worth seeing.) And, finally, in 2007 the series was resurrected for a brilliant homage/finale, distributed in English as Yo-Yo Cop, in which the original TV Saki, Yuki Saito, makes a cameo as the new Saki’s mother. All but the manga and TV series are available for purchase in English and I can’t stress strongly enough that you should at least see Yo-Yo Cop, because it’s pure genius.

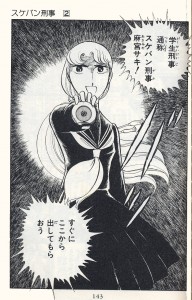

Once Saki agrees to work with the police, she’s told that they can’t actually release her from prison…she has to escape on her own. With the help of her jail friends, Saki escapes and makes her way to the police, where she is given a Yo-Yo as a weapon (since minors can’t carry weapons, a proscription that Saki occasionally breaks when needed.) In the Yo-Yo is the Chrysanthemum seal, which Saki displays to let the bad guys know she is an official representative of the police. (Much as the protagonist of Mito Koumon displays the Shogun’s seal to let the bad guys know they were caught red-handed and by whom.)

Saki is taken under the wing of a half-Japanese, half-American named Jin who acts as mentor and boss. Jin and Saki eventually fall for each other, but they are never actually a couple in the course of the series.

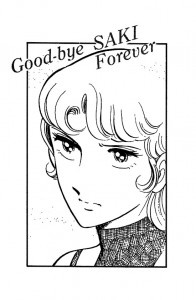

As Sukeban Deka, Saki is enrolled in various schools long enough to draw the attention – and eventually the wrath – of the local criminal bosses. Saki takes down the gang, then the bosses and transfers away to the next school. In the course of the 22 volumes of the manga, Saki loses her memory, ends up on the west coast of the US for a while, and then the east coast of the US for a while, until she regains her memory. Towards the end, Saki is transferred to one last post – in a juvenile detention center, rather than a regular high school. And this time, her enemy is not another student, but the evil warden himself, who raises giant snakes. Saki defeats the warden, of course. The final arc is the darkest, as she faces an adult criminal overlord. She wins, but at the sacrifice of…well, everything. Jin and she are finally united in death.

And death it is, as Wada Shinji makes perfectly clear on the last page. There will be no sequels of this series, as there were of Hana no Asuka-gumi or continuations as there were with YajiKita Gakuen Douchuuki. In fact, when the resurrections of those series brought girl gang manga back into the limelight a few years ago, Sukeban Deka was re-released as is, with no new material created.

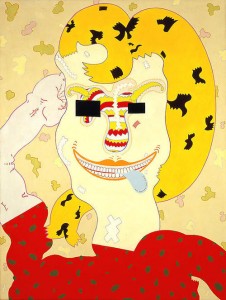

The art style Wada used rode the line between shoujo and shounen at a time when it was massively unpopular to do so. Saki might be shown with “shock!” eyes, or with a murderously intense expression, and action shots were quite common. This style left its mark on many a mid-80s series, including Asuka and YajiKita . It’s not unfair to say that we might never have had a Revolutionary Girl Utena, or PreCure if we had not first had had Sukeban Deka.

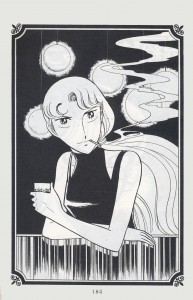

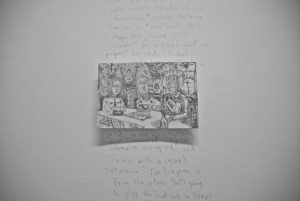

My collection of obscura includes a Saki figurine and a Sukeban Deka Yo-Yo. But it’s this one still from the manga that is my most prized possession of Saki. This image of 16-year old Saki on her off hours, drinking and smoking will never again be replicated in today’s sanitized manga world. Sukeban Deka is a paean to a world that is lost, a world that contained high school crime syndicates, gang girl violence and giant snakes.