Françoise Mouly, Art Spiegelman, Gerard Biard (CH editor in chief), Jean-Baptiste Thoret (CH film critic) and Salman Rushdie at the PEN awards. (photo by Jemal Countess/Getty Images)

Dear Mr. Spiegelman,

I’m addressing this to you, not as an empty rhetorical ploy, but to emphasize the fact that what I’m writing is personal. It always is. I’ve seen a lot of impassioned opinions about Charlie Hebdo offered in the guise of irrefutable pronouncements. I’m tired of reading cultural commentary from writers who act as though the objective truth fell, fully formed, from the sky and into their laps, the function of their words being to simply describe it. Their strange bloodless certainty, the pretense of personal remove, is central to comics commentary and reporting today, and at best it’s a farce.

There is no such thing as objective criticism or journalism; like comics, these forms are always, first and finally, an extension of the self. That’s perfectly natural, but it’s also limiting. What drew me to comics, and what I admire about your work, is its ability to explore and even exploit these limitations, locating truth (or something close to it, anyway) in the very process of acknowledging the obstacles we face as we try to perceive it.

I found myself thinking about subjectivity as I read Laura Miller’s piece about how you rallied comics luminaries to stand in for the six writers who dropped out of the PEN gala in protest of the organization’s plan to honor Charlie Hebdo. Which first of all, let’s face it, was sort of a dick move not unlike crossing a picket line. In one corner of Miller’s story we have you, Alison Bechdel and Neil Gaiman—the trifecta of literary comics—serving as champions of free speech and protectors of a maligned art form; in the other we have hundreds of unnamed writer types hissing like they’re something less than human at the survivor of a mass shooting. It’s a classic story of heroes versus villains. The headline, a quote from Gaiman, frames the faceless hoard’s take as pro-murder: “For fuck’s sake, they drew somebody and they shot them, and you don’t get to do that.” The implication is of course that the PEN protestors think that you should ~totally~ get to do that.

(Of course they don’t think that. Literally no one does.)

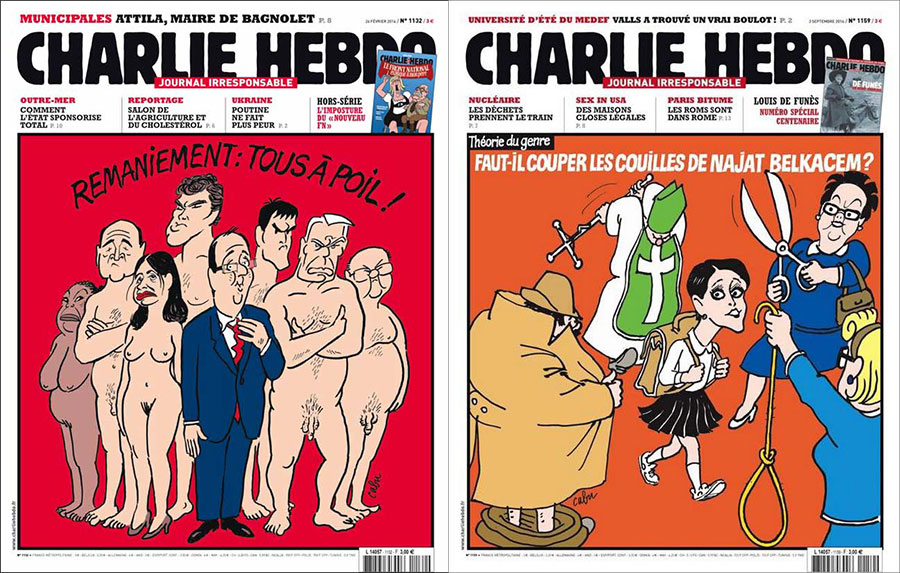

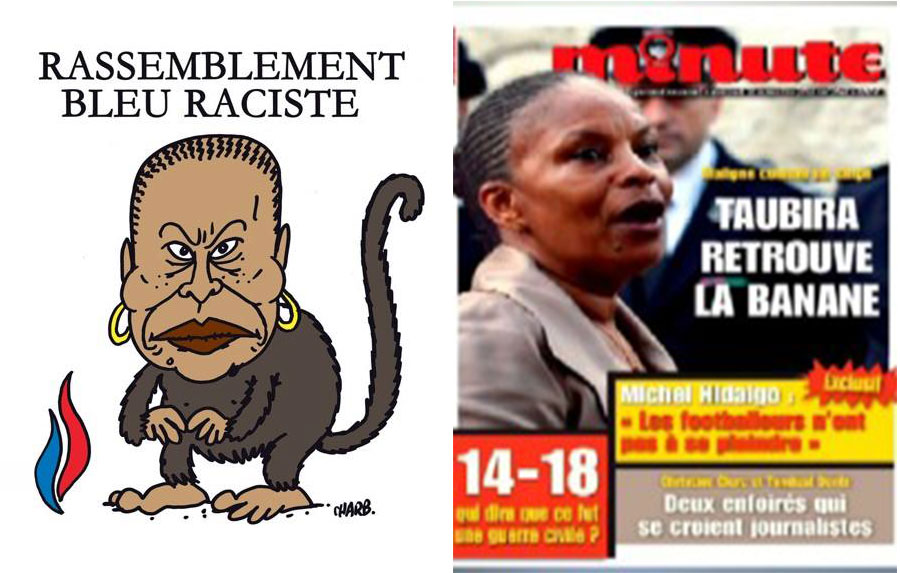

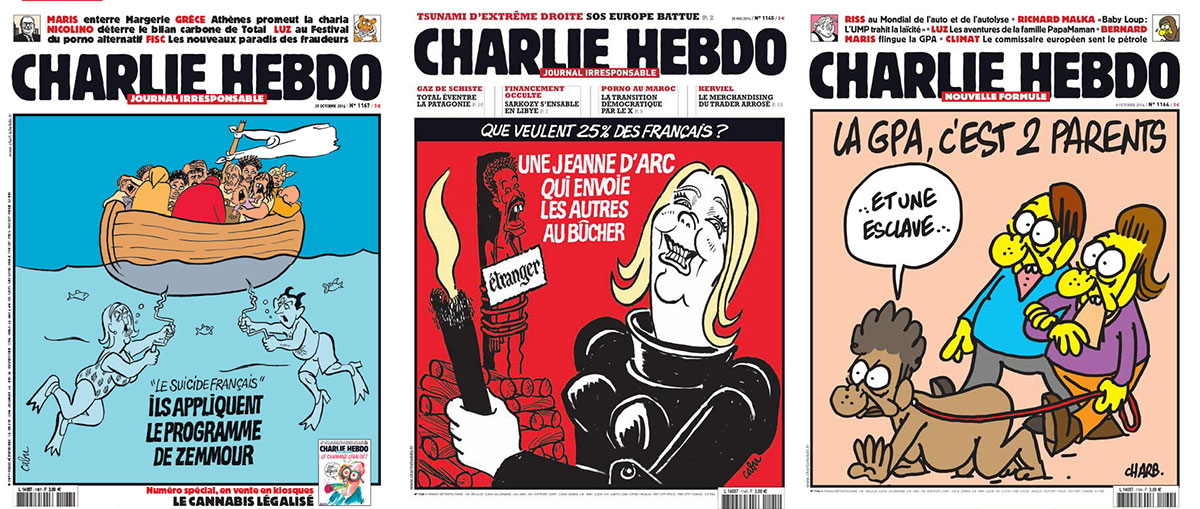

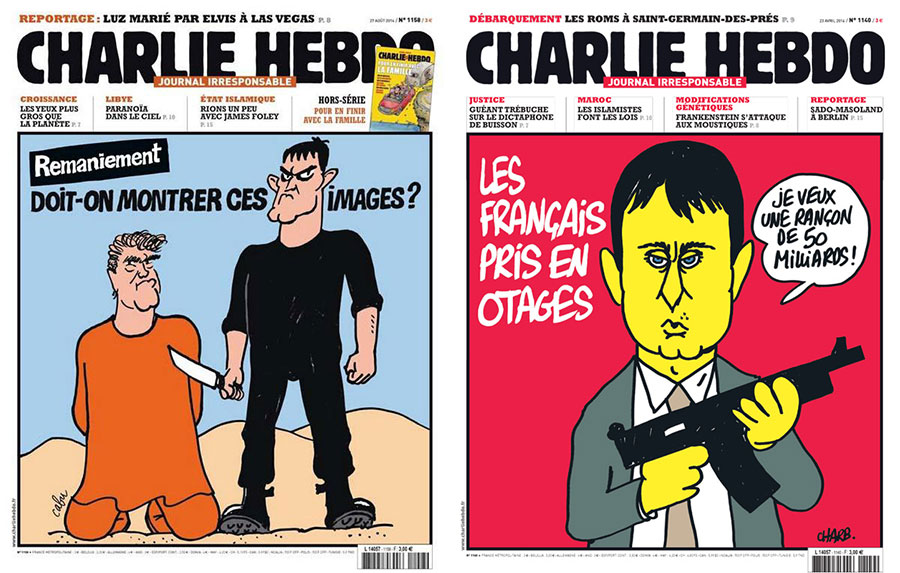

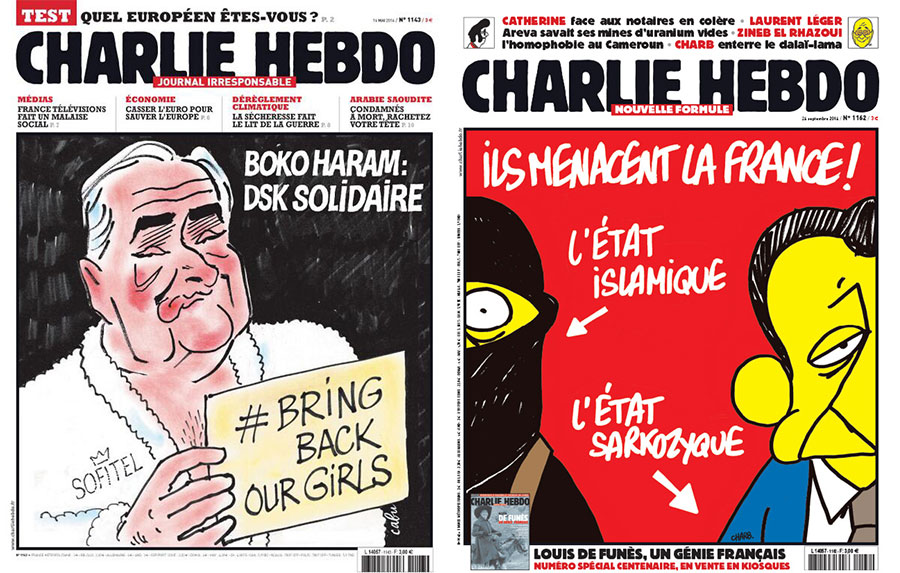

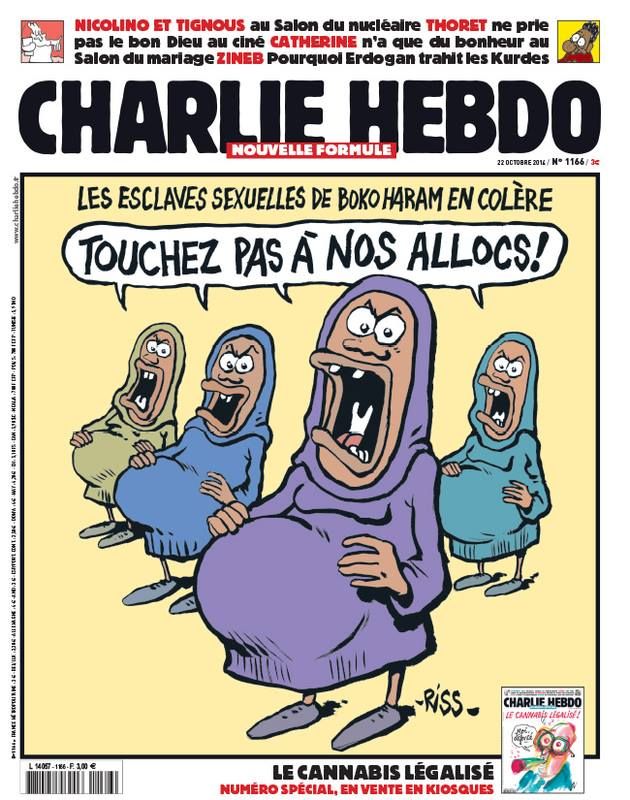

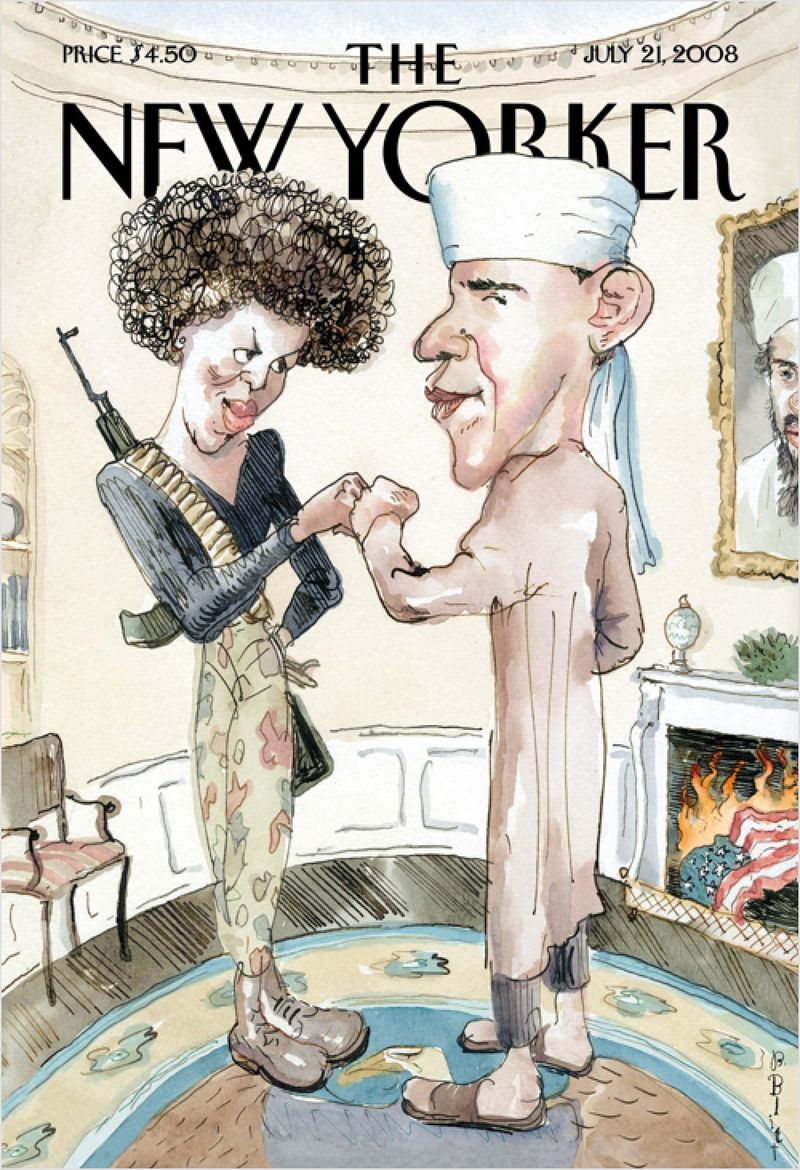

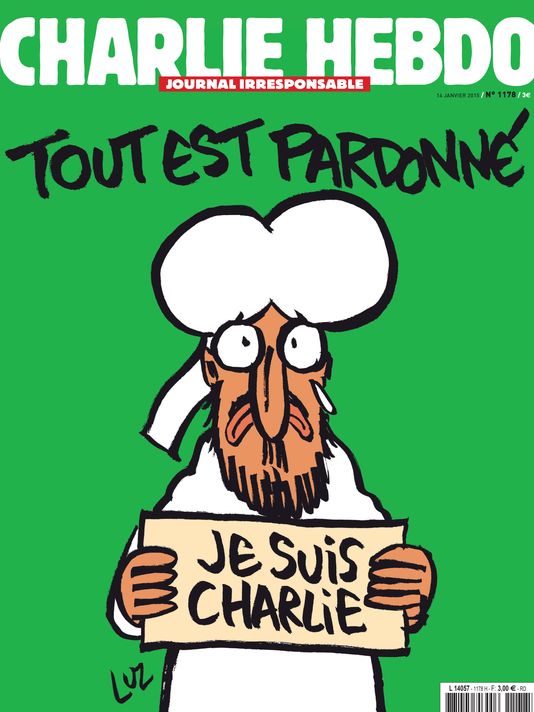

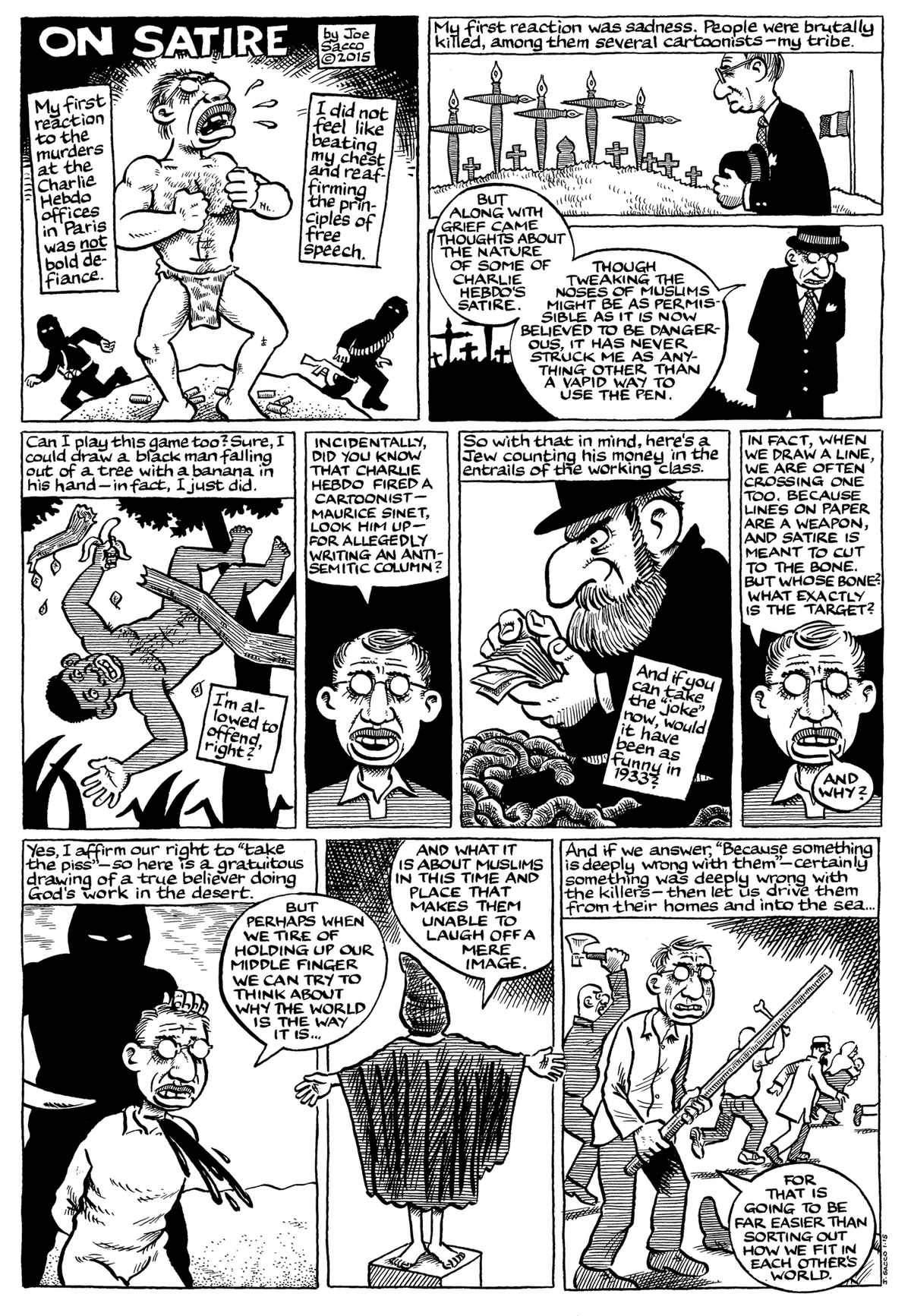

I’m not writing in an effort to change your mind about what I obviously regard as a racist publication, or to debate the validity of that PEN award, though it straight up makes me want to barf. I disagree with your opinion, but I also respect its right to exist. I have even tried to make room in my heart for the possibility that there’s some truth in what you say. While I find myself skeptical about how much expertise is required to, say, parse an image of a black person who’s been drawn as a monkey—and the tendency of experts like you to characterize other people’s “inexpert” reactions to images like that as unintelligent—I freely admit that you’re better informed than I on almost any given cultural milieu in play, including comics, satire, and the (supposedly) inscrutable kingdom of France.

Despite those vast stores of knowledge, you’re plainly no expert on race. Frankly, I’m not either, though I’m savvy enough to have recognized how ironic it was when you criticized readers for lacking sophistication even as you rallied a bunch of famous white people behind a slogan you appropriated from an oppressed minority. I don’t even know where to start with your unfortunate riff on “Black lives matter,” a movement that was spawned in protest of the George Zimmerman verdict, and reignited after the death of Michael Brown. Like “All lives matter,” the racist rejoinder to the original slogan, “Cartoonists’ lives matter” ignores one central fact: no one really thinks cartoonists’ lives are worthless except for their murderers, and they are all extremists who have been roundly denounced.

I really wish I could say the same for Eric Garner, or Tamir Rice, or Walter Scott, whose murders have been deemed, variously, as understandable and even warranted by public servants, the judicial system, people in my Facebook feed, and members of my own family. I don’t want to reduce our nation’s disregard for black lives to the deaths of those three people. It’s just that I’ve watched the indisputable evidence of their murders with my own two eyes, yet somehow still find them at the center of a bitter national debate. The “Black lives matter” slogan was borne in response to deep, appalling societal injustice, and my feeling watching you, a white man with uncommon privilege, adapt it in the name of propagating your opinion on the “bravery” of drawing Muhammad as a porn star lies somewhere far, far beyond my ability to articulate it to my satisfaction.

As a slogan, “Cartoonists’ lives matter” draws a false equivalence between one universally criticized attack and what has become a veritable institution of state-sponsored murder in our country. Where you attempt to make a comparison, it’s far more instructive to contrast. The Hebdo massacre was understood instantaneously, implicitly, to be of universal significance, and that’s because the killers represented the most hated enemy of the Western world—militant Islamism—and most of the slain were white. No one has disputed the dead’s status as innocent victims, though that position is routinely invoked as a straw man. They have been mourned all around the world for the better part of 2015.

Back in January, in an article for the New Yorker, Teju Cole asked readers to consider how the victims of Charlie Hebdo became “mournable bodies” in a global landscape where so many other atrocities are barely remarked upon, much less condemned. “We may not be able to attend to each outrage in every corner of the world,” he wrote, “but we should at least pause to consider how it is that mainstream opinion so quickly decides that certain violent deaths are more meaningful, and more worthy of commemoration, than others.” As it happens, Cole was one of the six dissenting writers who you and your friends replaced as table hosts at the PEN gala. Were you thinking of him, I wonder, when you told Laura Miller that your “cohorts and brethren in PEN are really good misreaders”? Do you really imagine that Cole, who is an art historian, doesn’t have the “sophistication to grapple with” comics? Or what about Junot Díaz, who was one of the 200-some writers who undersigned Cole’s decision? Like you, Díaz is a Pulitzer Prize-winner. His work has been illustrated by Jamie Hernandez, one of his heroes. Do you think that Junot Díaz doesn’t have the chops to read comics, Mr. Spiegelman? With respect, who do you think you are?

When you framed the Charlie Hebdo controversy as a matter of your vaunted expertise vs. what you call inexpert readers, you weren’t speaking in the abstract. You directly insulted the six writers who started the protest, as well as hundreds of their peers—individuals who wrote their names at the bottom of a letter, just as I’ll sign off at the end of mine. You also indirectly insulted countless other people in comics who object, publicly or privately, to “equal-opportunity offense” that somehow always, always manages to offend the same people no matter how many times old white men try to tell us that we’re just not reading comics right.

How is it that you failed to extend the basic courtesy of assumed literacy to those who struggle with the legacy of Charlie Hebdo? What does it mean for a white cartoonist to appropriate “Black lives matter” and then describe the argument of people who disagree with him—many of whom are people of color—as a failure of reading comprehension? Does your own mastery of the form really preclude the possibility that, say, Cole and Díaz, two of our smartest and most lyrical writers on race, might discern something in those images that you can’t (or won’t?) see? Or hey, what about Jeet Heer, who says that arguments like yours ignore the fact that aesthetics matter as much as intent? Is it just possible that you’re the one who’s not reading these comics correctly?

Look around you, man. Of course cartoonists’ lives matter. I realize that comics still has a whole thing about legitimacy, but Françoise Mouly’s assertion that the PEN protesters are literary snobs simply doesn’t track with the reality of comics culture today. Maus is more or less required reading in high school and college curricula. Neil Gaiman has more than 2 million followers on Twitter. Alison Bechdel is a MacArthur genius with a Broadway musical about her life. Tell me, did you actually hear anyone hissing at the PEN gala? It’s my understanding that Charlie Hebdo’s editor-in-chief received a standing ovation when he accepted that award.

I think of the work of you and Alison Bechdel and am flabbergasted that two people who built their careers on endlessly recursive autobiographies lack enough self-awareness to acknowledge the positions of privilege from which they speak. I don’t know what’s worse about “Cartoonists’ lives matter”—that it’s so masturbatory, that it represents such an egregious misunderstanding of the issues at hand, or that willfully misrepresents the positions of your opposition in lieu of engaging with them. You criticized the protest of the writers you glibly dubbed the “Sanctimonious Six” as “condescending and dismissive” even as you framed their argument as a fundamental failure of literacy. That’s not just hypocritical; it is demonstrably false. You leveraged your authority as the person who put comics on the map as a literary form to publicly smack down artists who are less famous than you simply because they objected to the valorization (not the existence) of Charlie Hebdo. That you chose to badmouth them in your capacity as Captain Comics (protecting a literary gala from evil, no less) is deeply embarrassing to many of us who care about this art form.

Unfortunately, it’s not just you. Your Hebdo comments follow a pattern I see all the time here on the bully beat at the Hooded Utilitarian: Comics calls for nuance when it’s in the service of understanding the transgressions of white men. But when it comes to the other side of the argument, opponents are characterized as unlearned, as uninitiated, as overreacting. Last week at TCJ Dan Nadel bemoaned how comics are still perceived as low culture by the ignorant masses. Increasingly I wonder if it’s the discourse surrounding comics that’s perceived as unsophisticated. It often caters to the sensibilities of white men who are forever foisting their racist sexist takes on comics onto the world under the noble guise of history. They actively alienate readers from other demographics, and routinely mock and celebrate that alienation. They (and you) dismiss people’s deeply felt reactions to comics’ trenchant racism and sexism as empty “political correctness,” stripping protesters of their very humanity, denying their capacity to think and feel in the genuine way that you do.

Your star shines brightly, Mr. Spiegelman, though I know you have a difficult relationship with fame. I often think about how, in a “corrective” book about Françoise Mouly’s many accomplishments, Jeet Heer chose to use your name twice (once more than Mouly’s) in the title. Heer’s shortcomings belong to him, not you, but I want to circle back on the point I began with: it’s impossible to extricate our individual experience from our work and beliefs. The things we find meaningful—what’s important to us, as well as what’s not—emanate from the place of deep personal bias on which we build a life. It’s always personal, an idea that Heer explores ably through the rest of that otherwise excellent book. But acknowledging those connections is a wholly different project than casting everything in their shadow.

The world is large, and each of us exists within it, not the other way around. It’s incumbent upon us to try to overcome our natural tendency to center everything on the self. Real criticism thrives in multiplicity. It can’t live in the certainty of a person who shoots down opposing points of view, whether it’s with bullets or rhetoric. It demands room for doubt.

Comics culture needs to face the uncomfortable truth that its faves are problematic, which is not to say they’re worthless or irredeemable. As the author of this letter, I can tell you it’s not a whole lot of fun. But I also believe that speaking honestly and openly about the flaws in the things we care about is even more important than celebrating an artist, promoting an art form, or defending a cause, however heartfelt our admiration may be.

Murderous terrorists have long been the known enemies of cartoonists everywhere. But the lack of empathy and cultural awareness you have demonstrated is a much more subtle, grave, and pervasive threat to the health of comics today. You’re in a unique position to promote meaningful conversation on a constellation of issues that matter to a lot of smart people. Take a long hard look at yourself, Mr. Spiegelman. You are failing.

Kim O’Connor

______

All HU posts on satire and Charlie Hebdo are here.