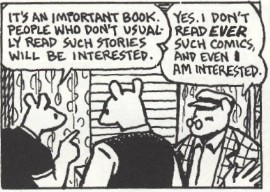

There are two main paths to liking Peanuts: the Snoopy way and the Charlie Brown way.

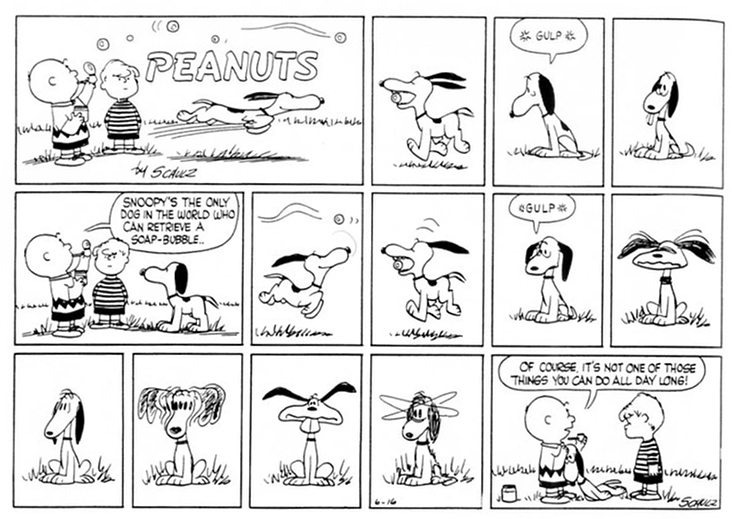

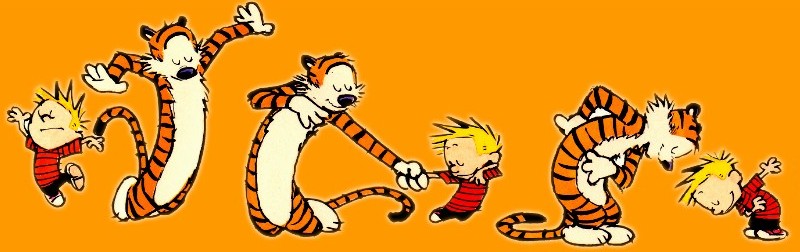

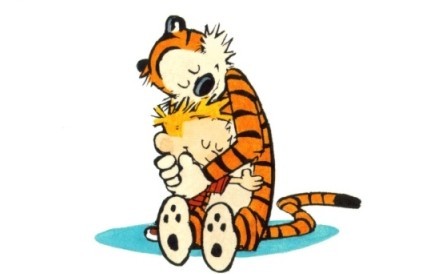

The Snoopy way focuses on the strip’s plush centerpiece; the irrepressibly imaginative and adorably ill-proportioned polymorphous people-pleasing juggernaut. Snoopy combines Hobbes’ furry lovableness with Calvin’s mischievous bad-boy allure; he’s cuter than Hello Kitty and more whimsically unpredictable than Opus. His is a face that launched a million lunch boxes and a massive life insurance campaign—he’s the personification of Schulz’s marketing genius. If there were a cute overload of the funny pages, it would have an outsize schnozz and curse at the Red Baron. Snoopy is Peanuts for the masses.

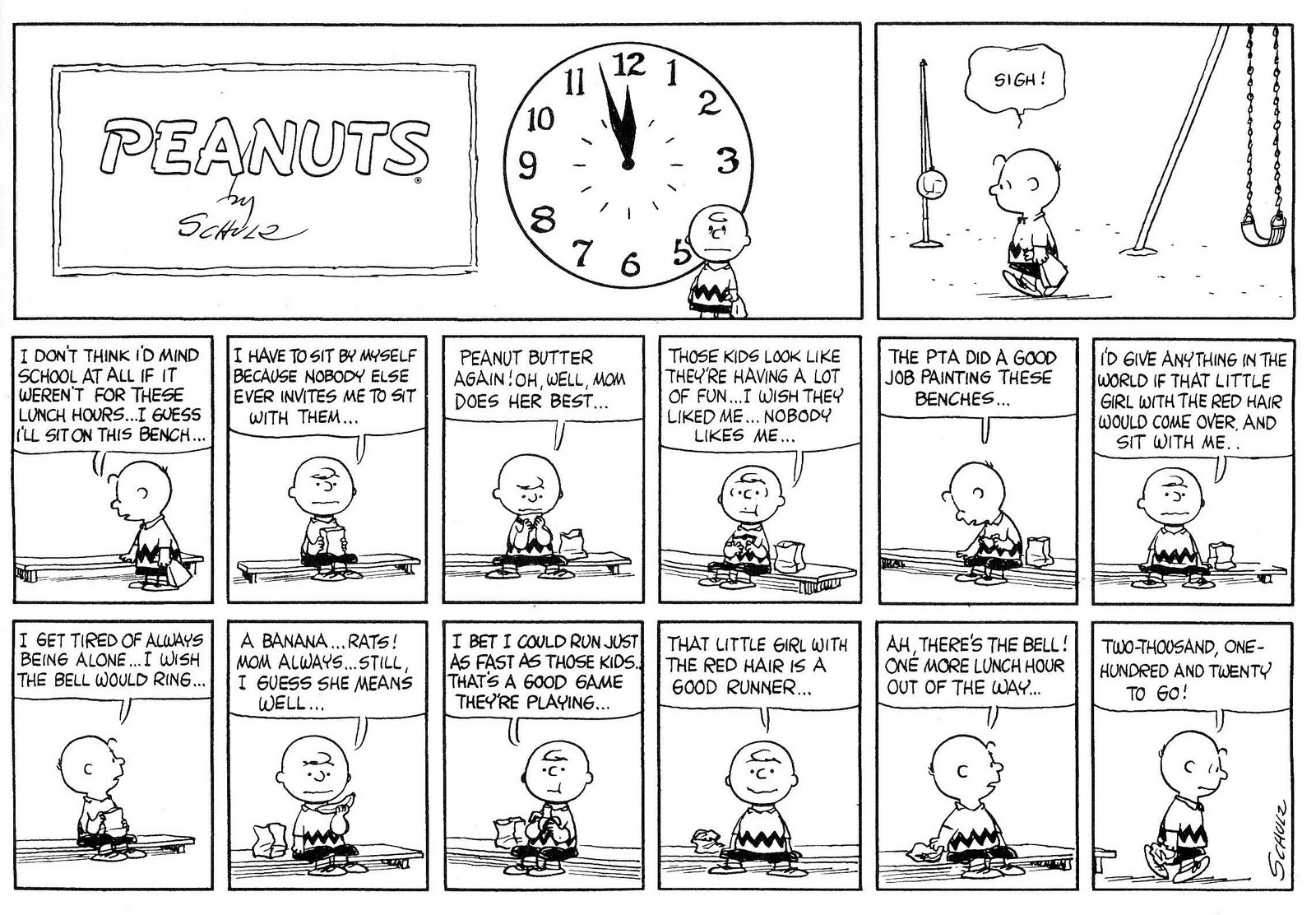

The Charlie Brown way focuses on the strip’s doleful centerpiece; the downtrodden, self-pitying loser and the endless variations on his losing. Charlie Brown is existential tragedy in a baseball cap. The numbing, torturous repetition as he tears apart his sandwich while watching the red-haired girl from across the playground, or the agonized howl as he strikes out yet again—this isn’t a charming diversion for the kiddies. This is a bleak vision. Charlie Brown is Peanuts for those with depth.

I actually like both Snoopy and Charlie Brown, separately and together. I find Snoopy irresistible—especially in Schulz’s earlier strips when he looked more dog-like, and when Schulz’s then-fluid line-work gave the character a vivacity that outshone even James Thurber, much less Jim Davis. And Charlie Brown is not only Beckett in miniature; he’s Beckett realizing that miniature tragedies are, through their very trivialness, even more heart-wrenching than grandiose ones. There’s some dignity in waiting for God…but waiting to finally kick the football? Transcendent cuteness and transcendent despair—a strip everyone loves, and which the people who hate what everyone loves can also love.

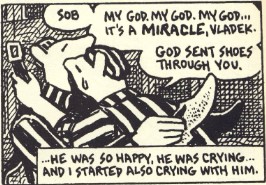

Still, I think that the focus on Snoopy and Charlie Brown can sometimes obscure the other players. Many of these characters, of course, have more than a touch of the stars in their make-up. Schulz drew an awful cute baby in his heyday, and it doesn’t get much more heartwarmingly precious than Linus sighing as he holds his security blanket. On the other hand, Lucy’s pursuit of Schroeder, or Linus’ pursuit of the Great Pumpkin, are as painfully hopeless as any of Charlie Brown’s repetitive failures.

But Linus and Lucy and Schroeder aren’t just a little bit Snoopy and a little bit Charlie Brown. They’re characters in their own right, with their own idiosyncrasies. Schroeder with his Beethoven obsession and his miraculous musical ability; Lucy with her determined crankiness and equally determined confusion; Linus with his contradictory nervousness and spiritual insight — they seem to have stepped out of Dickens, not out of Kafka or a marketing campaign.

Maybe the best example of this is Peppermint Patty. Patty was introduced in the ‘60s as the mercilessly competent leader of the opposition baseball team; a foil for Charlie Brown’s haplessness. Over time, though, she took on added depth, becoming one of the most complicated, and most featured, characters in the strip. Some of Schulz’s most hilariously extended narratives involve Peppermint Patty’s uncanny inability to grasp the obvious—it takes years before she realizes that Snoopy is a dog and not a funny-looking, big-nosed kid, a misapprehension that leads her to take obedience training classes, much to the disgust of her sidekick Marcie.

Schulz doesn’t just use her as the butt of jokes though. Some of his most affecting strips touch gently on Peppermint Patty’s ambivalent relationship to her tomboyishness. It’s always clear that she enjoys her ability at sports…but she also at times seems to wish to be a pretty girly-girl. She grins ear to ear when relating that her father calls her “a rare gem,” or boasts about him giving her roses for her birthday. And there’s a lovely moment when she and Lucy are planning to get their ears pierced when she looks over and declares, “I have no doubts about my femininity, Lucille!” It’s a joke because it’s a kid saying that—but it’s not really a joke on Peppermint Patty. On the contrary, it seems like a quiet affirmation; she can be a tomboy and a girl. Schulz loves her as both.

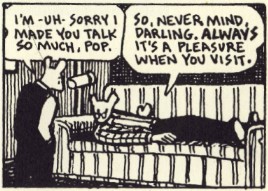

It’s easy to miss, maybe, how much love there is in Peanuts, and how much life. The strip was so long-lived, and so great on so many levels, that some of its achievements get buried. Like, for example, the fact that it arguably introduced the best three or four female characters on the funny pages—not just Peppermint Patty, but Lucy, and Sally and Marcie are surely some of the greatest women, or girls, to ever come out of the brain of a guy, be he novelist or screenwriter or artist or comics creator. If you like charming, Peanuts is charming, and if you like dark, it’s dark, but it isn’t just charming, or just dark, or even just charming and dark. There are countless ways to like Peanuts, which is no doubt why it—deservedly, inevitably—tops this poll.

Noah Berlatsky is the editor of The Hooded Utilitarian.

NOTES

Peanuts, by Charles M. Schulz, received 50 votes.

The poll participants who included it in their top ten are: Derik Badman, J. T. Barbarese, Eric Berlatsky, Noah Berlatsky, Corey Blake, Alex Boney, Scott Chantler, Jeffrey Chapman, Brian Codagnone, Dave Coverly, Warren Craghead, Tom Crippen, Katherine Dacey, Alan David Doane, Paul Dwyer, Andrew Farago, Bob Fingerman, Jenny Gonzalez-Blitz, Steve Greenberg, Geoff Grogan, Paul Gulacy, Charles Hatfield, Jeet Heer, Sam Henderson, Abhay Khosla, Molly Kiely, Kinukitty, T.J. Kirsch, Terry LaBan, John MacLeod, Vom Marlowe, Robert Stanley Martin, Chris Mautner, Todd Munson, Mark Newgarden, Jim Ottaviani, Joshua Paddison, Michael Pemberton, Stephanie Piro, Andrea Queirolo, Ted Rall, Joshua Rosen, Giorgio Salati, Kevin Scalzo, Tom Stiglich, Matthew Tauber, Jason Thompson, Mark Tonra, Matthias Wivel, and Jason Yadao.

Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts was a daily newspaper strip that began publishing on October 2, 1950. The final original daily was published on January 3, 2000. The final original Sunday strip was published February 13, 2000. In an eerie coincidence, Schulz passed away the night of February 12.

Reprints of the strips are published in newspapers to this day under the title Classic Peanuts.

There have been innumerable book collections of the strip published over the years. A complete, chronological 25-volume hardcover collection, titled The Complete Peanuts, is currently in progress, with 15 volumes published to date.

For those looking for an inexpensive, one-volume introduction to the series, the best choice is probably Peanuts Treasury. It is published by MetroBooks, and available for sale in the discounted book section of most Barnes & Nobles. A nicely printed hardcover collection, it retails for $9.98. The book reprints over 700 strips (over 100 of them Sundays) from between 1959 and 1967, the time considered by many to be the strip’s peak period. Click here to go to its product page on the Barnes & Noble website.

–Robert Stanley Martin