When did the Silver Age of comics end and the Bronze Age begin? There’s no definite year, but the 1973 “SNAP!” of Gwen Stacy’s too-perfect neck in Amazing Spider-Man #121 is a contender. 1970 is a bigger year, with Jack Kirby’s move from Marvel to DC, plus the start of Neal Adams and Dennis O’Neil’s Green Lantern / Green Arrow. Steve Ditko left Marvel for Charlton in 1966, turning both Spider-Man and Doctor Strange over to new artists for the first time. Marvel veteran Bill Everett took on Doctor Strange with Strange Tales #147, but for me Strange Tales #154 is the sea-changing Silver-to-Bronze moment. It’s the first episode of Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.E.I.L.D. that the recently hired Jim Steranko wrote, penciled, and inked in 1967.

Like other artists Marvel hired in the 60s, Steranko imitated Jack Kirby, first auditioning by inking two of his penciled layouts for a proto-S.H.E.I.L.D story, and then by adopting the Kirby-defined Marvel house style. Gil Kane, who started freelancing at Marvel in 1966, explained during a 1985 panel discussion at the Dallas Fantasy Fair:

“Jack’s point of view and philosophy of drawing became the governing philosophy of the entire publishing company and, beyond the publishing company, of the entire field…. They would get artists, regardless of whether they had done romance or anything else and they taught them the ABCs, which amounted to learning Jack Kirby…. Jack was like Holy Scripture and they simply had to follow him without deviation. That’s what was told to me, that’s what I had to do. It was how they taught everyone to reconcile all those opposing attitudes to one single master point of view.”

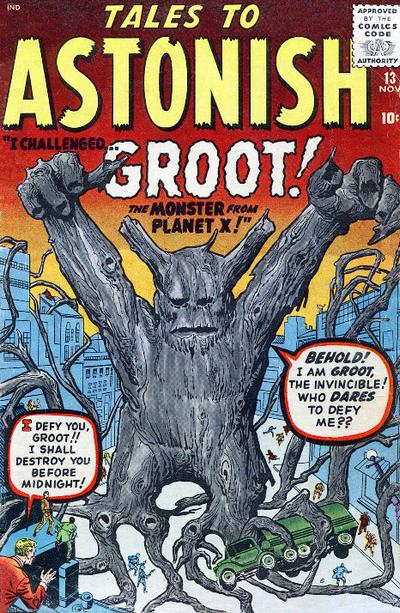

After passing his employment test, Steranko apprenticed by inking three of Kirby’s twelve-page Nick Fury episodes. Kirby had co-created the series with Lee in 1965, but after the inaugural Strange Tales #135, nearly a dozen different artists had worked on the title. Kirby also co-penciled the two issues leading up to Steranko’s run, which suggests that Steranko’s credited “illustrations,” “artwork,” “rendering” may include more than just inking. Kirby is credited only for “layouts,” and they certainly look like his. Issues #151-3 are a close match to Kirby’s first Nick Fury episode:

#135: Seven regular 3-row pages

(including three implied 3x2s),

three regular 2-row pages (including two implied and one actual 2×2),

and two full-page panels (including the opening splash).

#151: Ten regular 3-row pages (including four implied and two actual 3x2s), one regular 2-row page, one full-page panel (splash).

#152: Ten regular 3-row pages (including seven implied and two actual 3x2s) one regular 2-row page, one full-page panel (splash).

#153: Nine regular 3-row pages (including seven implied and one actual 3×2), two regular 2-row pages (one implied and one actual 2×2), one full-page panel (splash).

Kirby draws no irregular layouts, so panel heights are consistent on each page and, since three-quarters of the layouts are regular 3-row based, across a majority of pages too. Of the thirty-six 3-row based pages, twenty-six are also 3×2 (typically implied, occasionally actual). The percentage is higher in Kirby’s last two issues, with seventeen of nineteen regular 3x2s. All rows include either one, two, or three panels of equal width. When he does vary from 3-row layouts, he uses 2-rows instead, averaging two 2-row pages per issue. Each issue begins with a full-page splash panel and ends with a 3-panel row in a regular 3-row page. Excluding full-page panels, each issue includes between five and eight pages with a full-width panel; twice in one issue, two full-width panels appear on the same page. Kirby draws no full-height panels or sub-columns, so all reading is horizontal. All panels are also rectangular and framed by gutters. Kirby draws no insets or overlapping panels. The overall effect is lightly varied and highly orderly.

The Nick Fury layouts changed with Steranko’s first solo issue:

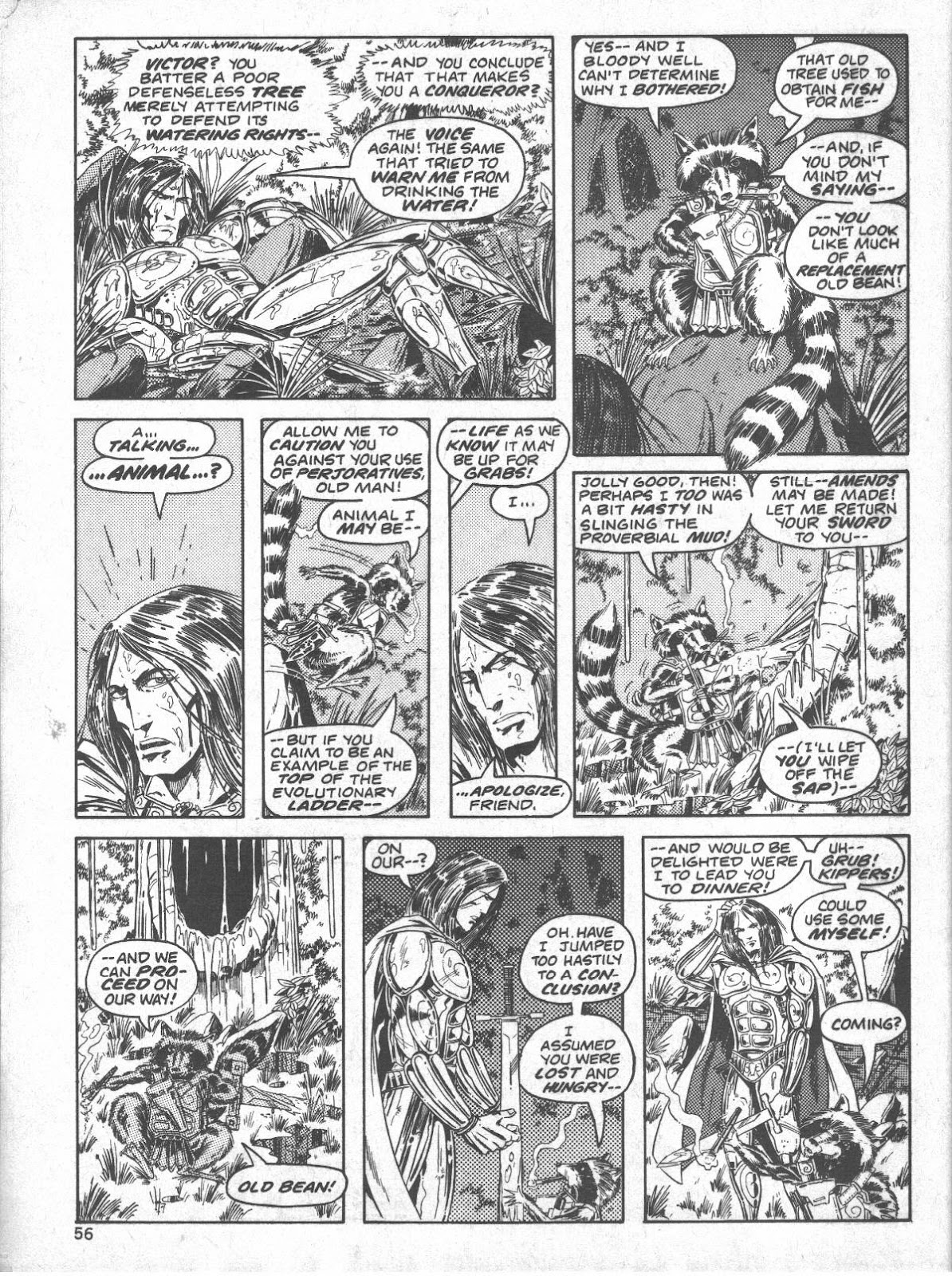

#154: Four regular 3-row pages (including one implied 3×2), three irregular 4-row pages, two full-page panels (including the opening splash), one irregular 2-row page, one regular 2×3, one mixed column-row page.

Only three of Steranko’s layouts appear in Kirby’s issues: two full-page panels and an implied 3×2. Like Kirby, Steranko favors regular rows, although not exclusively. Unlike Kirby, Steranko’s 3-row based layouts are a minority, comprising one-third rather than three-quarters of the total pages, and where slightly more than half of Kirby’s pages are 3×2 based, Steranko’s one implied regular 3×2 is the rarity.

Three of Steranko’s regular 3-row pages lightly modify Kirby by including three new elements. First, two rows are divided into four panels; Kirby’s rows never exceed three panels. Second, some panels are irregular, and so their widths vary within the same row; Kirby’s panels are always divided equally. Third, two full-width panels include insets, effectively creating a row of two irregular panels; Kirby draws no insets.

Six of Steranko’s layouts contradict Kirby completely: three irregular 4-rows;

a regular 2×3; an irregular 2-row; and a mixed column-row page. Although the final page features the first instance of vertical reading, the concluding two-panel sub-row echoes the regular 3-panel row that concludes each of Kirby’s issues too.

Despite the range of differences between Kirby’s #153 and Steranko’s #154, most of Steranko’s additions can be found in Kirby’s earlier work:

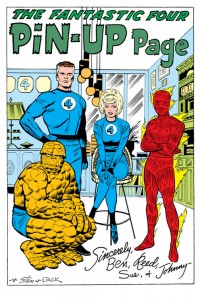

The Fantastic Four #1 (August 1961) includes irregular 4-row pages, regular 2x3s, rows of four panels, and rows of irregular panels. Fantastic Four #2 include the same variations, but 4-rows and 2x3s vanish afterwards.

With the exception of splash pages, The Incredible Hulk #1 (May 1962) is also entirely regular 3-row based, with only three pages that vary the format with irregular panels or a regular four-panel row.

By The Avengers #1 (September 1963) Kirby’s layouts are also almost entirely 3-row based, with no more than three panels per row, and only two rows of irregular panels; the one irregular 2-row implies a 3×3 grid.

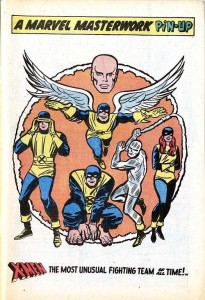

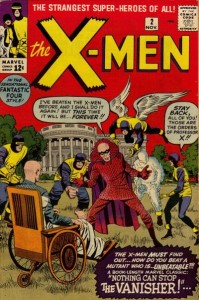

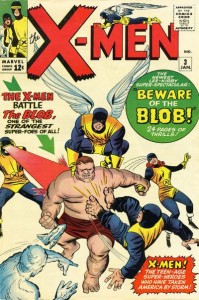

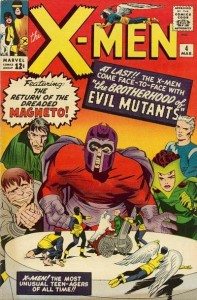

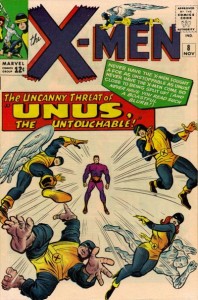

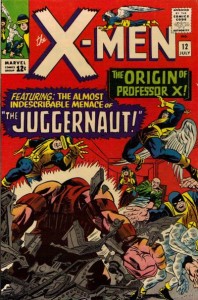

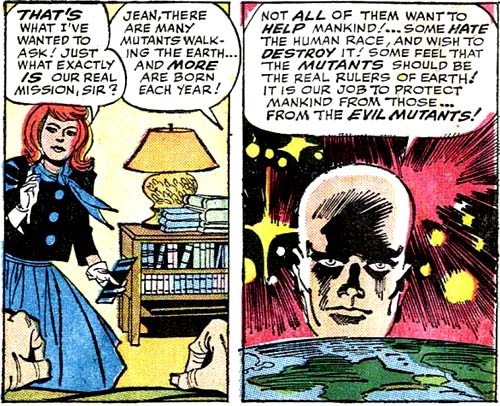

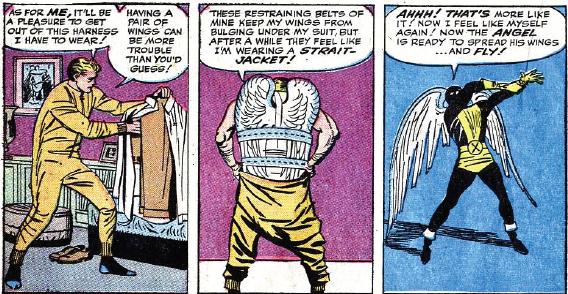

The X-Men (September 1963), published simultaneously, has even fewer variations: a subdivided panel in a regular 3×2, and one row of two irregular panels.

The twelve pages of Kirby’s Captain America feature in Tales of Suspense #59 (November 1964) are even more rigid, containing only regular 3-row layouts, all but one implying a 3×2 grid.

The Nick Fury episode of Strange Tales #135 (August 1965), Kirby’s last new series for Marvel, is comparatively diverse. Becoming the Marvel house style seems to have required Kirby to regularize his layouts, presumably so they could be more easily imitated. Variation and innovation are not qualities easily taught, and they do not produce a unified style across titles.

Although Kirby appears to have curtailed his own style to create the Marvel house style, insets and columns are still rare in his early Marvel work too. Fantastic Four #3 does include one, partial inset with its own gutter, and #5 features a highly atypical 1×3 page—which Steranko echoes in his next Nick Fury issue with a three-column page of his own.

One of Kirby’s very first comic books, the eight-page “Cosmic Carson” in Science Comics #4 (May 1940), includes four sub-columns, but no page-height ones. The following year, Captain America #1 includes sub-columns too.

“Cosmic Carson” also shows Kirby’s early use of a regular 2-row with a top full-width panel; identical layouts appear in Strange Tales #s 135, 151, and 152 as well as Steranko’s later #157.

Overall, however, Kirby uses columns rarely, while for Steranko they would become part of his signature style. His next column concludes #160, then beginning with #166, at least one appears in nearly every issue. #166 includes two: a regular 1×2 and, more distinctively, an irregular 1×2 in which the first column is an unframed, full-height figure defining the panel edges of the second column.

#167 includes no columns—in part because of its seven full-page panels, including Steranko’s innovative fold-out “quadruple-page spread,” which also doubled the price of the issue from twelve cents to twenty-four.

#168 then includes three columned pages in a row: an irregular 1×2 with no panel divisions;

an irregular 1×2 with the first column divided into five regular panels; and a highly irregular 1×2 in which the unframed full-height figure overlaps with the three panels of the second column.

Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D then switched to its own independent title, and #1 featured another irregular 1×2 with an unframed, full-height figure.

#2 includes a lone column and a later half-column of insets on a full-page panel, as does #3, and #5, Steranko’s last, includes a new column layout of a regular 1×3 with only the middle column divided into six irregular panels.

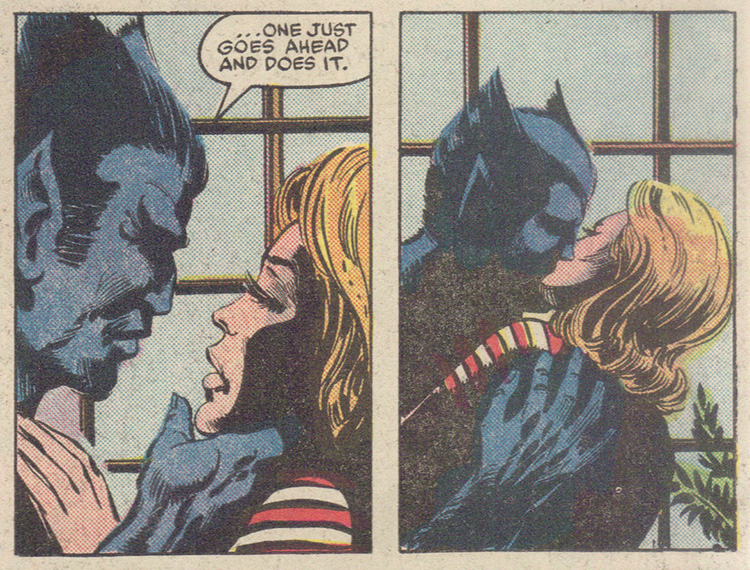

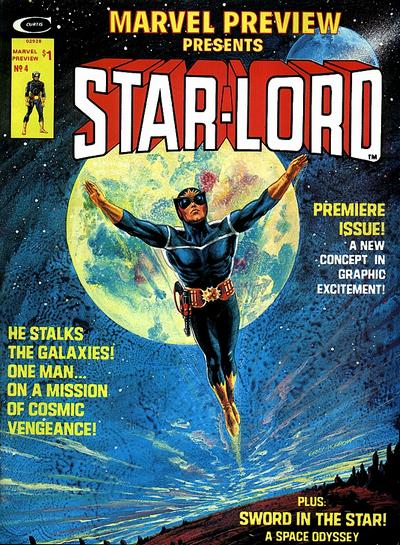

Because Steranko fell behind schedule, another creative team filled-in #4, marking the beginning of the end for Steranko at Marvel. He would leave the following year, 1969, after objecting to Stan Lee’s editing of his work. Steranko’s penultimate issue, Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D #3, bears little relationship to Kirby’s earlier layouts:

1: full-page splash panel

2-3: mixed column-row, a two-page panel with a column of letter-shaped panels

4: irregular 3-row with irregular panels

5: irregular 2-column with three irregular insets over the page-panel

6: irregular 3-row with two insets in the middle row and one inset in the bottom row

7: irregular 2-row with two full-width panels

8: mixed column-row, beginning with a full-width panel, followed by a nearly full-page panel with a two-panel column of insets

9: mixed column-row, an irregular 3-column of full-height columns, with a top row of four regular insets

10: regular 3-row with irregular panels

11: mixed column-row, an irregular 2-row with a two-panel column of insets over a full-width half page bottom column

12-13: two-page panel

14: irregular 3-row with irregular panels

15: irregular 3-row with irregular panels and one inset

16: mixed column-row, an irregular 3-row with a three-panel column of insets over a middle full-width panel

17: irregular 3-row with irregular panels and one inset

18: irregular 3-row with irregular panels

19: irregular 2-row with a column of text beside a nearly full-page panel

20: mixed column-row, an irregular 3-row with a sub-column of two insets

Although nine of the twenty pages are exclusively row-based, only one features rows of uniform height, and six additional pages include a mixture of rows and columns. The complexities are greater when also considering unframed and overlapping panels, but the contrast to Kirby’s last issue, published a year and a half earlier, is already stark:

1: Full-page splash panel

2: regular 3×2

3: regular 3-row with top full-width panel implying a 3×2

4: regular 3-row with middle full-width panel implying a 3×2

5: regular 2×2

6: regular 3-row with middle full-width panel implying a 3×2

7: regular 3-row with bottom full-width panel implying a 3×2

8: regular 3-row with bottom full-width panel implying a 3×2

9: regular 2-row with a top full-width panel implying a 2×2

10: regular 3-row with a bottom full-width panel implying a 3×2

11: regular 3-row with a bottom full-width panel implying a 3×2

12: regular 3-row

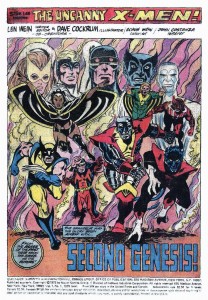

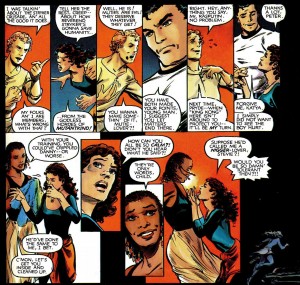

Kirby built the Marvel house style on a 3×2 grid and punctuated it with an occasional 2×2. After both Kirby and Steranko left Marvel, Kirby’s flexible page schemes would give way to a norm of irregular layouts, fluctuating between 2-, 3-, and 4-rows, with an open base pattern.

Kirby’s Silver Age layouts were gone.