AUTHOR’S NOTE: I wrote this piece fresh after finishing the show, and there were a lot of things I was oblivious to at the time that deserve a mention now. I read a feminist message in Madoka and I still like to hold onto how the show made me feel. But a more substantial and well-rounded analysis should take into consideration these factors: that tons of my friends who are women who know a lot more about Magical Girl anime than I do hate it! I later learned that the show’s creator intended a specifically sexist message, and that the darkness was supposed to be some sort of corrective to the “flaws” he saw in Magical Girl Anime, and that male fans of the show are encouraged to be as gross as they like re: objectifying the characters. So take my reading with a grain of salt!

“Chucking her under the chin, he said, “What are you doing here, honey? Your not even old enough to know how bad life gets.” /// “Obviously, Doctor,” she said, “you’ve never been a 13 year old girl.”

Jeffrey Eugenides, The Virgin Suicides

Madoka and Homura by Magical Quartet

That’s a rough lead-in to writing about a Magical Girl anime, but if the shoe fits…

Reading Noah’s article in the Atlantic this morning got me thinking about different shades “princess” roll models for girls and boys. Since I have no day job, an indulgent partner and a crunchyroll subscription, I had already found a great example when I marathoned the entire twelve-episode run of Mahou Shoujo Madoka Magica (or Puella Magi Madoka Magica as released in the US) in one day. It’s an extraordinary show; a queer love story and maybe not exactly a deconstruction, but a purposeful re-envisioning of the Magical Girl concept and the way it is at this point rotely marketed to young girls.It’s been a big hit, and possibly (hopefully) will have a similar cultural impact as defining Mahou Shoujo properties like Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura in time. NOTE: It will be difficult to discuss the major themes of this show without revealing how they are woven into pivotal plot points. Some things must be spoiled, but I will do my best to remain discreet.

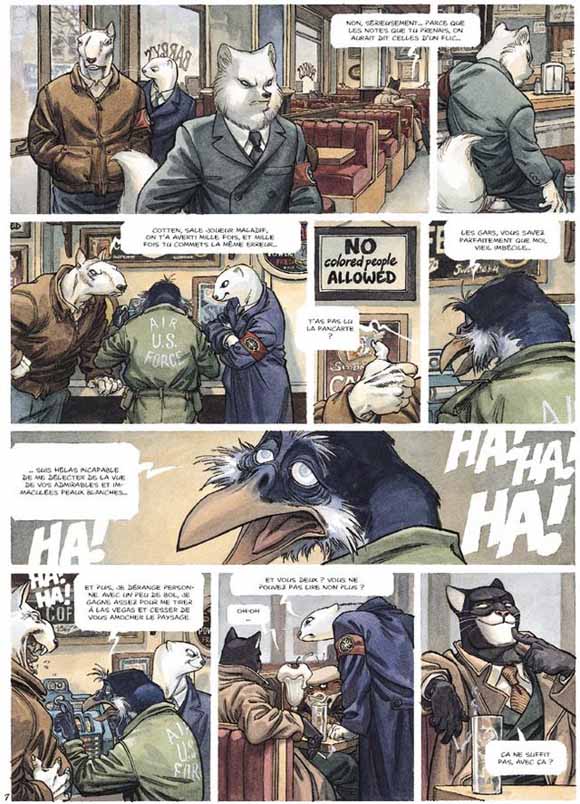

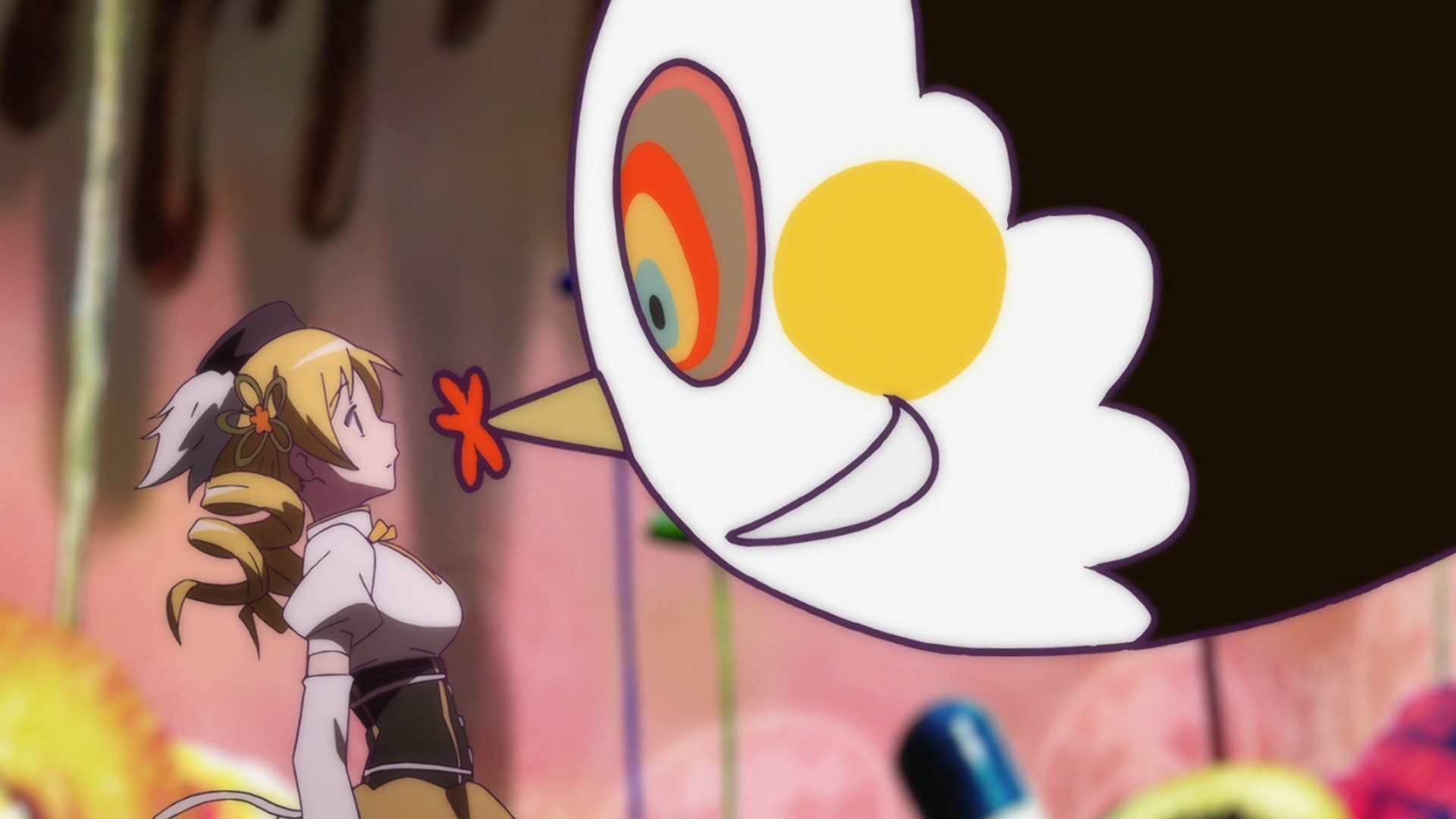

Contrary to many Mahou Shoujo predecessors, the tone of Madoka is generally BLEAK, and our titular hero, Madoka Kaname, isn’t actually a magical girl. We begin with her as an “ordinary” eighth grade magical girl protagonist. She’s good natured, sweet and comfortable, with close friends and a successful businesswoman mom and loving dad to look up to. It’s her ordinariness contrasting with her descending deeper into the secret world of Magical Girls and the unseen Witches they fight that defines the narrative tension of the show. Witches spread unseen despair and psychological torment on unsuspecting humans, and it is suggested that they are generally responsible for humankind’s chaotic woes. Magical girls are ordinary teens who make a contract with kyubei, an elegant, sinister white cat-like familiar who grants them one miraculous wish as well as unique frilly costumes (of course!) special weapons and a soul gem, the source of their power.

It’s revealed quickly that Magical Girls must give up contact with their past life as they must continuously defeat witches, not just in the pursuit of justice and love, but for their “grief seeds” which purify the Magical Girls’ soul gems and replenish their power. Giving up their initial idealism for a kind of mercenary nihilism turns out to be the first and most vital tactic for survival. It’s the first of many revelations that kyubei omits from the initial contract negotiations, and a key to why Homura Akemi, a cold-blooded and mysterious Magical Girl will stop at nothing to prevent Madoka from accepting Kyubei’s bargain.

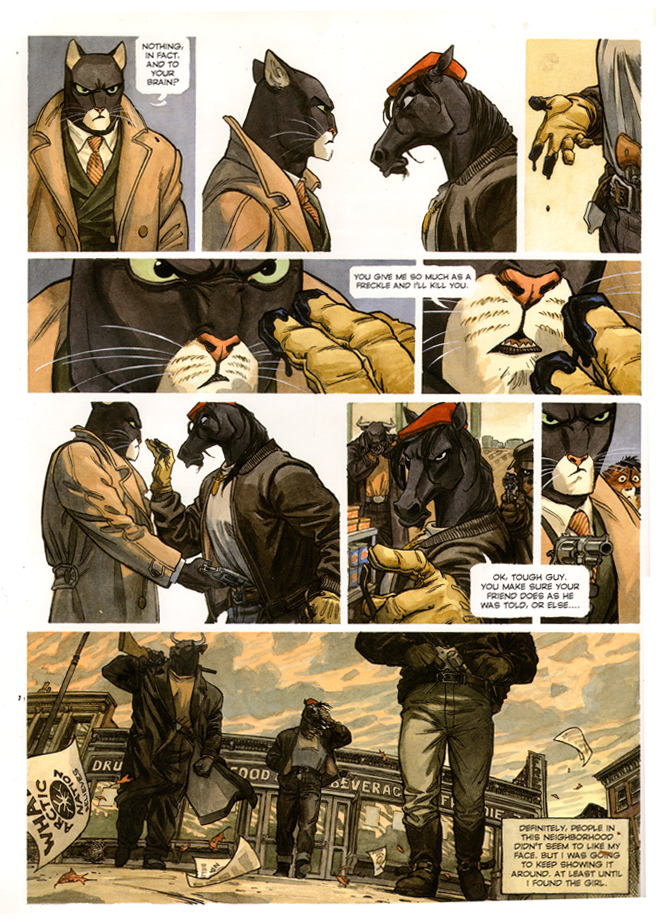

The setting of Madoka is a Magical Girl show where a teen girl’s volatile emotions, constantly demeaned by society, are the source of her power and her struggle for self-determination is locked in the greater karmic push and pull of hope and despair. It’s a world in which the hidden struggle of extraordinary young women against a byzantine structure of hopelessness and cruelty is the engine of all human civilization. The imposed price is living within a predatory system of oppression, where their bodies are not their own, their sacrifice is unacknowledged and their consent is trivialized.

Madoka is also a love story, one that grounds some of its most emotionally powerful scenes in nude intimate embrace between young girls without sexualizing them. This is remarkable itself, in a landscape of anime that is pathologically unable to NOT sexualize young girls. Just in my CR queue, Ano Hana is a somber meditation on friendship and grief where the main male protagonist perves over the ghost of his dead childhood friend, Hanasaku Iroha is a sensitive coming-of-age story about a girls and their mothers with wildly deranged notions about appropriate ways to deal with a sexual predator, Bakemonogatari is like, male gaze the anime, the most consciously and purposefully misogynistic cartoon I have ever seen that isn’t Heavy Traffic… What point is there in going on like this? Madoka is better than all this, and focuses instead on the deepening friendship, intimacy, tenderness, and trust that keeps the girls in sight of why they began fighting in the first place when the decks are stacked impossibly against them, and agony and hopelessness are a total certainty. Of course love saves the day, it is a Magical Girl Show, but a bittersweet, impersonal, abiding love that runs deeper than even the karmic balance of hope and despair.

I assume many parents would cringe at this Madoka show as a new “princess” model, what with the violent dismemberment and depersonalization and unsentimental atmosphere of hopelessness that’s bleaker than a diamond made from the compressed essence of a thousand Watership Downs, but kids know better. How many girls are sold a frilly dress and magic wand and are treated terribly, whether they take it or not? Madoka is an ordinary girl whose ordinariness, her naivety in the face of danger are her ultimate strengths, and her love of her friends the ultimate defiance of the system that exploits them. Also her pink outfit and rose-stem inspired magical bow and arrow are super cool.