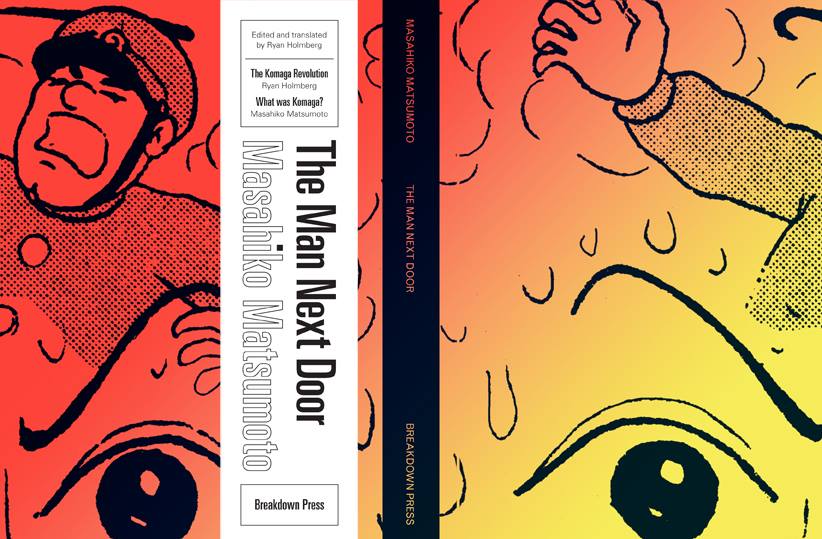

This October, London’s Breakdown Press published Masahiko Matsumoto’s The Man Next Door, the second in their new art manga collection. Curated by art historian Ryan Holmberg and featuring Breakdown’s characteristic risograph technique, the anthology of four stories highlights much of what makes the young collection such a unique aesthetic proposition.

The collection is heir to the “Masters of Alternative Manga” line, one of the two that Holmberg helmed for Picturebox, Inc. Only one volume came out before Picturebox announced that it wouldn’t produce any new books, an anthology of short stories by cult author Seiichi Hayashi called Gold Pollen and other stories. (Two books came out in the other collection, called “Ten Cent Manga” : Tezuka’s highly entertaining The Mysterious Underground Men and the less accessible Last of the Mohicans, by underappreciated pioneer Shigeru Sugiura.)

While the Ten Cent Manga series remains orphaned, the Alt Manga collection has sparked the interest of other publishers, and what should have been the follow-up to Gold Pollen, an anthology of shorts by Tadao Tsuge titled Trash Market, will be published by Canada’s venerable Drawn & Quarterly. Tadao, the younger brother of alt manga superstar Yoshiharu Tsuge, was a fixture of the GARO magazine in the late 60’s and early 70’s, and an obsessive chronicler of social anxieties in a Japan still haunted by the war.

The D&Q connection makes perfect sense in the light of their previous interests in manga publishing. The Breakdown Press one is less intuitive, and the particularities of its inception are a big part of what makes it so original and exciting.

The London-based publisher is distinctly inspired by zine culture. They printed all their first books using a Risograph machine, a piece of Japanese office equipment that blends screen printing and photocopy, and which has proved very popular recently among underground publishers. They met Holmberg while he was in England for a fellowship at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Art & Culture. The institute and the Japan Foundation were looking to invite Hayashi to England, and “I wanted to do something to commemorate the event”, says Holmberg. Breakdown Press happened to be looking for that kind of projects, and the planets aligned. They settled on a 1969 story of loneliness and rural exodus, Flowering Harbour ; Holmberg wrote an introduction and translated an article by Hayashi, while Breakdown Press’s first published author and de facto art director Joe Kessler handled the design and printing with Victory Press. The result, a 40-page, 5.4” by 7.6”, perfect-bound book, resembles neither the mass-produced commercial manga nor the large hardcovers of other classics collections. As Breakdown’s Simon Hacking explains, “What we really loved about the Flowering Harbour project was the opportunity to work with a cartoonist who is much more established and revered than any we’d worked with before, but to do so in a format that matched our existing output. Printing the book using a Risograph at the printer we’ve used for all of our books, and getting Joe Kessler […] to design the book allowed us to make a 40-year-old comic from the other side of the world feel like part of our line.”

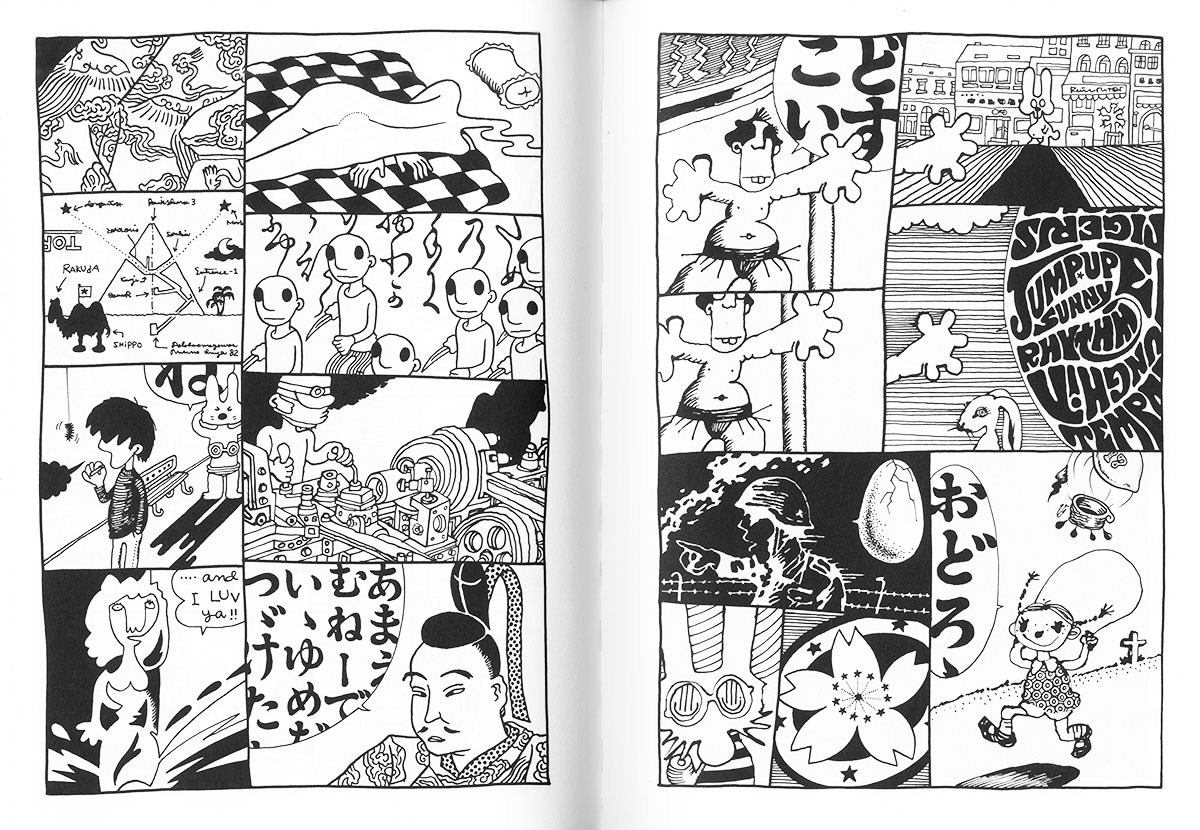

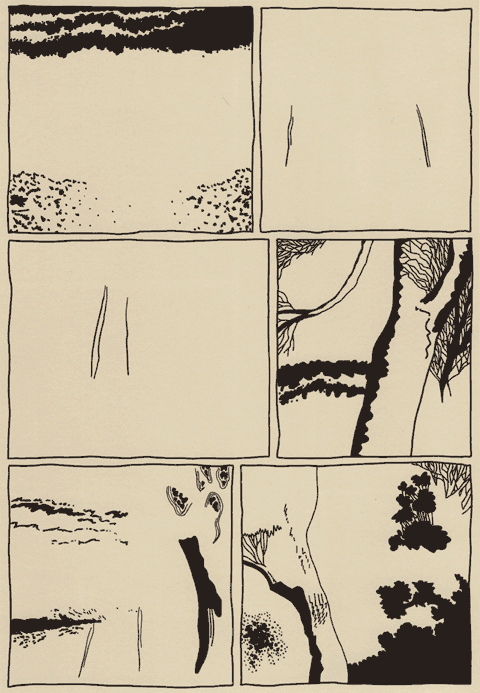

On September 23rd, the Cartoon Museum in London launched the “Gekiga” exhibition, an occasion for Holmberg and Breakdown to publish another short piece of comic history. The Man Next Door collects four stories (including the titular “Man Next Door”) by Masahiko Matsumoto, the least known but most discreetly influential of the members of the Gekiga Workshop (more famous peers being Golgo 13 creator Takao Saito and comic giant Yoshihiro Tatsumi, who later told – and in a way rewrote – the story of the gekiga revolution). Again, Holmberg wrote an introduction and translated a 2004 article by the author himself. Kessler designed the book and the Risograph was put to good use. Each story is printed in its own colour, a great detail since all anthologies nowadays are printed in black, while the magazines themselves often used colored ink.

The homemade touch of the books and the “opportunistic” character of the line-up manage a strange feat : they make the works feel current. Their origins and historical context are obviously explained, but the articles in the books themselves are introductions : short, to-the-point and easily digested. They don’t break the spell that preserves these strange little books from the “glass dome” curse of patrimonial anthologies. And for those who would like to delve much deeper than that, Holmberg actually accompanies each release with lengthy and much-researched discussions on the authors and stories as part of his TCJ column “What was alternative manga ?”.

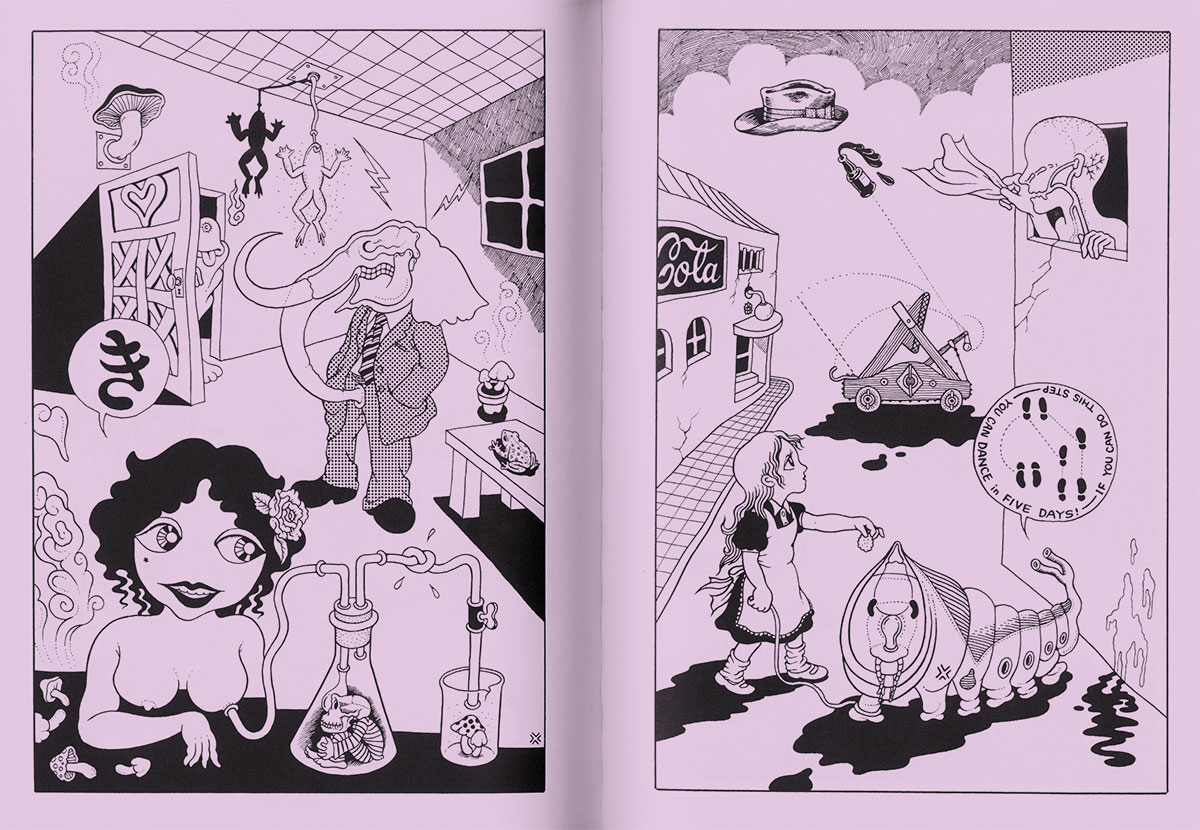

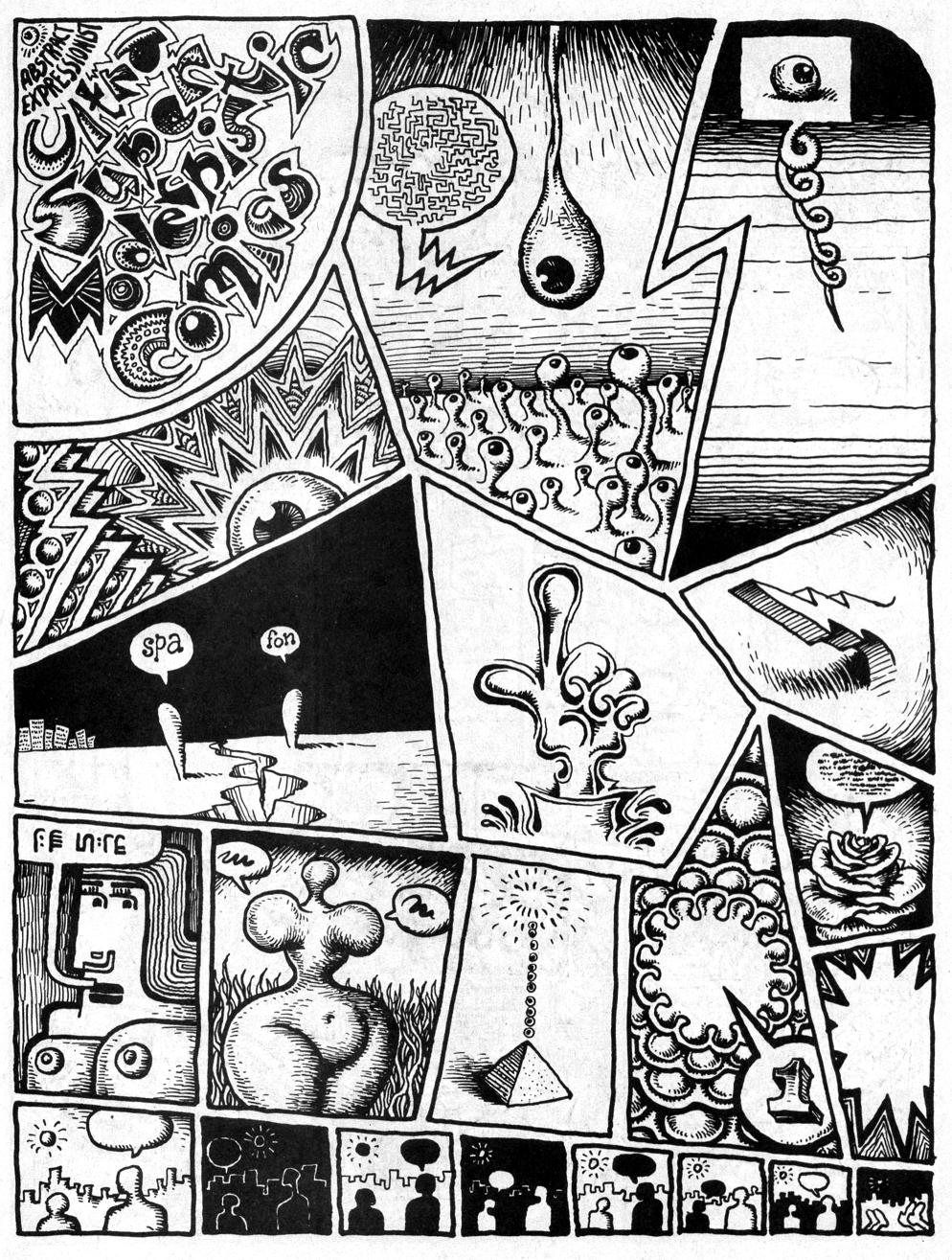

But as fascinating as the experiment has been so far, its most exciting developments are still to come. Because Breakdown Press are at exactly the right moment in their history, in terms of size and ambition, to tackle some big, crazy projects. Starting with a reputedly unpublishable masterpiece of alt comics, the experimental anti-manga of Sasaki Maki. Despite the enduring success of Maki’s Complete Comic Works in Japan, Holmberg had up to now failed to have an anthology edited in English. “I remember pitching a Maki collection to Dan Nadel at PictureBox many many years ago, 5 or 6 years ago, and he said, no way! no story = no sales.”

Admittedly, the short stories Maki drew in the 60’s and 70’s are among the most abstruse ever produced, but strolling through this seemingly meaningless interweaving of political, symbolic and pop imagery is an experience like few others. For every fan of the psychedelic era, or anybody interested in seeing what Japanese counterculture looked like at the height of its creative drive, this is essential reading. And it’s no wonder that the best-selling (though himself often obscure) novelist Haruki Murakami defines the artist as the defining voice of the period. “With my novels, he confesses in the foreword to Maki’s Japanese collection, I try to do for this generation what Sasaki Maki did for mine.”

Though the anthology, scheduled for the beginning of 2015, won’t have the same look as the mini-manga published so far, it will certainly have the Breakdown feel, especially since Joe Kessler is now their official house art director. And if their latest offerings, printed in offset for greater versatility, are any measure, it is going to look gorgeous. Of course, it’s not like anybody involved is hoping for great financial success, but even if it all goes terribly wrong, let’s hope that the initiative will spark many copycats. Because these little classics feel different, and new, and imply in their own humble way that the range of what small press can do has suddenly broadened.