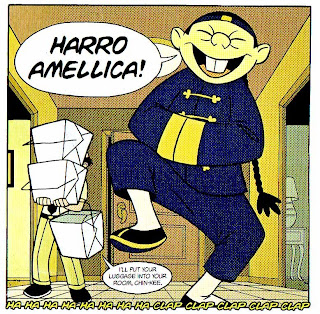

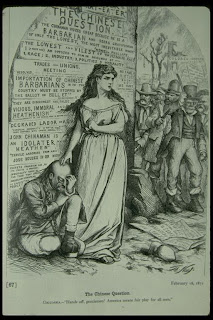

It’s easy enough to rake comics over the coals for their viciously racist past, for all the loinclothed cannibalistic African savages with bones through their noses rampaging across jungle stories, for the puffy-lipped google-eyed Ebony “Mistah Spirit”ing this and “Mistah Spirit”ing that. (Ebony’s replacement, the parka-garbed, spear-toting Eskimo tot Blubber was hardly an improvement, though he was quieter, nor can replacing both with white kid Sammy exactly be seen as a step up.) Certainly there are mountains of that material littering comics history – jeez, Winsor McKay, practically the father of comics, whose whole worldview, at least as expressed through his work, can be summed up as whimsical, turned out a considerable body of appallingly racist material all by himself, from his first strip Tales Of The Jungle Imps through the odd support character Flip in Little Nemo In Slumberland – and from our vantage it’s easy to ignore the cultural context. Ebony originated as a horrific stereotype but Eisner, embarrassed by the character in his twilight years, was correct in reminding critics Ebony was largely the best of a bad lot. Hitler may have given comics their key supervillain, but the pulp magazine delivered comics’ key conspiracy, the Yellow Peril, a compartmentalized edition of the greater paranoia, fear of the Non-White Races.

If anyone thinks I’m inventing this conflation, I direct you to Robert E. Howard’s 1929 pulp novel, Skull-Face, whose eponymous Atlantean wizard rises from an eons’ long sleep in the ocean depths to be

“the leader and instigator of a world-wide movement such as the world has never seen before. He plots, in a word, the overthrow of the white races!

His ultimate aim is a black empire, with himself as emperor of the world! And to that he has banded together in one monstrous conspiracy the black, the brown and the yellow… When it comes, I look for a simultaneous uprising, against white supremacy, of all the colored races – races who, in [World War I], learned the white men’s ways of battle, and who, led by such a man as Kathulos and armed with white men’s finest weapons, will be almost invincible.

… I know not… what power Kathulos has that draws together black men and yellow men to serve him – that unites world-old foes. Hindu, Moslem and pagan are among his followers. And back in the mists of the East where mysterious and gigantic forces are at work, this uniting is culminating on a monstrous scale…”

And on and on, feverishly describing how western civilization and all its achievements and advances out of superstition will be wiped from the earth, and what few white men remain will be made slaves while white women become sex toys etc. (Much of the Yellow Peril’s unspoken appeal was this thrill of illicit, if vicarious, sex.) This was hardly original with Howard, who wrote Skull-Face as a Fu Manchu pastiche, and Fu author Sax Rohmer inspired multitudes of pulp writers a lot more garish than Howard, and Rohmer was only expressing the paranoid undercurrents of imperialism, the impossible, unthinkable fear that inferior peoples might reject the “gift” of westernization and someday rise up against their imperial masters. We’re not exactly free from those undercurrents even today; the national (or cultural, if you want to include western Europe with America) horror of Muslims in the wake of 9-11 was out of all proportion to the event, pulled off by a miniscule and not especially influential Muslim splinter group if they can be considered “true” Muslims at all, and the specter of the “destruction” of Western Civilization is pretty common these days in right wing literature. The idea of the “non-white peril” is so much a part of our current political background noise that most of us now only hear it as, no pun intended, white noise.

Neither Howard nor Rohmer were likely frothing racists; if you assess his output collectively, Howard seems to have been rather ambivalent toward race. Whether he scorns non-white races or praises them, and he’s no stranger to either, depends almost entirely on plot necessity. (In fact, he tends to praise more often where it serves no specific plot purpose but fleshes out characters.) By and large, pulp magazines were no place for progressive social views, and comics inherited that along with a lot of other pulp baggage, less an agenda than an acquiesence to the “white noise” of the day. The heyday of the Klan wasn’t that far behind Depression era America, and while a few Americans looked with trepidation at the rise of Nazi Germany, many more fretted over a militarized Japan. Race paranoia made for useful political ploys; to facilitate public outcry against it in 1937, hemp was “officially” renamed marijuana specifically to evoke images of Mexican drug dealers seducing virginal white womanhood with it at the same time pot was being reimaged as a “Negro” narcotic, for the same basic allusion. While I wouldn’t doubt there were flagrantly racist (meaning beyond the “white noise” systemic racism of the era, with specific intent to do harm to one or more minorities) editors and publishers involved in pulps and comics, it strikes me as likely, given my own experience, that ambivalence was the controlling factor in their portrayals of race.

Ambivalence is the great underwriter of systemic racism, found at every level of pop culture, and it’s particularly effective because it shifts the blame and transforms the enforcers into helpless victims of the process. Mainly, stereotypes are enforced not because it’s easy or because anyone involved in the creative process necessarily likes the stereotypes, but because the audience would be offended by any digression from the stereotype. In pop culture, the consumer is king – except the consumer has no direct input into content. Not “offending” – ie. challenging the preconceptions of – the consumer is standard operating procedure in media even today. While the logic flaw is that editors (and, by extension, the talent creating the work for the magazines they edit, whose real audience is the editor) begin from a preconception of what audience preconceptions are. That they’re frequently not wrong is where the vicious circle principle cuts in: editors make editorial decisions based on preconceptions of what consumers want, the material reinforces consumer preconceptions, and the purchase of the material reinforces editorial preconceptions.

When it came to race in comics, positive portrayals generally caught a lot more flak than negative ones. How many complaints did all the quasi-naked cannibals in jungle comics generate over the years? But when the astronaut in a ’50 EC Comics science fiction strip- integration/racial tolerance metaphor took off his helmet in the last panel to reveal he was a black man the Comics Code tried (unsuccessfully, fortunately) to get his race changed. DC’s early ’70s introduction of John Stewart as “the black Green Lantern,” the company’s first prominently displayed black hero, prompted a major distribution chain to dump the book, tailspinning it to cancellation. I doubt it’s accidental the Black Panther, Marvel’s debut black hero and briefly The Black Leopard when his original name became politically hot, was racially concealed head to toe on covers, while Kirby’s original design featured a revealing half-mask. His primary black foe, the feral Man-Ape, an almost perfect rendition of the voodoo/cannibal African stereotype, appeared prominently on covers without raising a retailer eyebrow. Really think the lesson most editors would learn from that is to buck the system?

I have to say I didn’t give a lot of thought to matters of race when I began writing comics in the late ’70s. (Then again, I had a rather sheltered childhood; the only time I ever heard the N word was in reference to stable boy statues – and all those where I grew up had white skin. That’s Wisconsin for you.) But it didn’t take me long to figure out minorities and women were more interesting characters to write, because unlike with white male heroes editors didn’t demand they be heroic at all times. This occurred to me after I wrote a Spider-Man story where he gets involved in a fight he really has no stake in besides pride, and when he realizes he can continue the fight or catch his cross-country flight home, he takes the flight. It got published, but I was thereafter told in no uncertain terms that no matter what Spider-Man does not run away from a fight! There was no use in arguing that when I grew up on the Lee-Ditko Spider-Man, he was no stranger to running away from fights. AKA white male heroes must be heroic at all times. I never got that pressure when writing minority or female characters; they were “allowed” (mainly by lower editorial expectations, I think) to make more human decisions for more human reasons. It wasn’t that editors were either specifically racist or felt those characters should have greater emotional latitude.

They were just ambivalent toward those characters, without thinking about it one way or the other, and they weren’t ambivalent about white male heroes. Corporate think was that audiences expected their heroes to be heroes. It’s just their heroes were white. It’s no secret that white heroes (though not all white heroes) outsold minority heroes; the question’s why. Because white readers refused minority characters? Because minority readers had no interest in minority characters? Because the writers, artists and editors handling those characters perpetuated stereotypes that miffed the minorities they were intended to appeal to? All of the above?

Bear in mind this was in the late ’70s/early ’80s when comics and American culture in general were finally willing to at least pay lip service to the notion of multiculturalism. (Nascent MTV was still unwilling to scare off viewers with “black” videos, though.) Things like early white writers having Luke Cage deride himself as “just a big dumb monkey,” though appalling, usually weren’t even vestigial racism. They were mis-transplanted Sgt. Furyisms. Then there was the “big picture” syndrome, perpetuating racism as counter-racism: Fu Manchu and the Yellow Claw can still dress in Mandarin drag, having fifteen inch fingernails and a string beard to match, and concoct hideous giant venomous spiders in their labs while preaching the destruction of the decadent West, ‘cuz, see, here’s heroic gi-clad (half-)Asian Shang Chi heroically defending our way of life, and there’s heroic American superspy Jimmy Woo, who looks just like us. If that’s not balance, what is?!

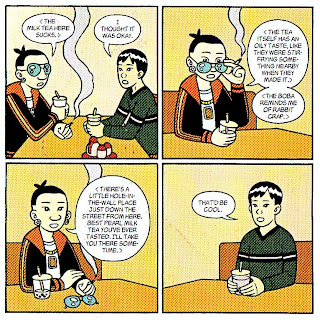

Jimmy Woo’s a key figure here, not because he’s a heroic Asian but because he’s a bland heroic Asian. In comics, the opposite of racism isn’t anti-racism but genericism. The problem, again in American pop culture across the board, is that middle class white America has always been the baseline. In comics in particular, with its natural emphasis on iconography, the appeal of racial stereotypes in most instances is less racist agenda than departure from the baseline to spice things up. Steve Englehart’s reconstruction of The Falcon as a superflyin’ pimp transformed into just the sort of Sidney Poitier wannabe to pluck Captain America’s liberal heartstrings is merely acknowledgement that pimps are more interesting than social workers. But that’s an underlying problem of minority characters in comics. To the extent they skew toward the baseline, they’re dull. To the extent they skew away from the baseline, they veer toward stereotype. (In comics, we call stereotypical characters “iconic.”) A side effect of multiculturalism is the wider variety of stereotypes, “good” and “bad,” we now have to choose from.

The baseline is its own curse. White males don’t bear the onus of “white issues”; minority characters are rarely considered “real” unless they confront issues pertinent to their race or sexuality. (Even most gay characters identified in comics eventually get an After School Special confronting gaybashing or AIDS, like those are the most overriding elements of gay life.) To the extent minority characters behave like white male characters, or don’t confront their identifying issues they may as well be white male characters. It’s a catch-22 of dealing with race and gender, again not restricted to comics. But in that strange way it reinforces the baseline and identifies it as “normal,” the same way the tumult of American life over the past 50 years has widely reinforced a flawed perception of ’50s America, which was in no way free of tumult, as “normal.”

As others have mentioned, we now look at The Spirit’s Ebony White, Tarzan’s black cannibal warriors, yellow-skinned Ming The Merciless slavering over Dale Arden’s porcelain beauty, and a million bloodthirsty redskins in a million cowboy comics, roll our eyes, wistfully shake our heads and write it all off as (collectible) products of a “simpler” time. But though the product has adapted to the times the market forces that produced all that and more are still with us, and as long as iconography is the main selling point of comics they’re going to be. The logic loop of “the Market” is driven not by hate but by ambivalence, swinging whichever way the wind blows at any given moment in pursuit of sales, of tapping into the zeitgeist, but in practice ambivalence is only half a step up from hate, and not necessarily preferable just because it means no harm.

_______________

Update by Noah: You can read all posts in the roundtable here.

Update2 by Noah: Steven is too much of a gentleman to promote himself, but if you are not reading his column at CBR, you’re missing out.